The human eye, that most expressive feature of the face, has held profound significance across ancient cultures as both a physical organ and a powerful symbol of divine connection, spiritual authority, and cosmic understanding. Yet the artistic treatment of eyes in ancient art reveals a fascinating paradox: the earliest human representations often deliberately omitted eyes entirely, while later civilizations would make them the most prominent and exaggerated features of their sacred art. This evolution from eyeless figures to the hypnotic, oversized gazes of Mesopotamian votive statues, Egyptian deities, and Greek kouroi reflects not merely changing artistic techniques, but fundamental shifts in how ancient peoples understood the relationship between the human soul, divine authority, and cosmic order.

The journey from the faceless Venus of Willendorf to the piercing stare of Sumerian temple guardians illuminates how different cultures conceptualized vision, consciousness, and spiritual power. Through examining the artistic treatment of eyes across ancient civilizations, we can trace the development of complex mythological and cosmological systems that placed vision at the center of human experience and divine interaction.

The Eyeless Beginning: Paleolithic Anonymity

The Venus of Willendorf, dating to approximately 25,000 BCE, represents one of humanity’s earliest artistic attempts to capture the human form. Yet this iconic figurine, along with dozens of similar “Venus figurines” found across Paleolithic Europe, conspicuously lacks facial features entirely. Where we might expect eyes, nose, and mouth, we find instead a textured surface suggesting hair or a headdress that completely obscures the face.

The Venus of Willendorf, dating to approximately 25,000 BCE, represents one of humanity’s earliest artistic attempts to capture the human form. Yet this iconic figurine, along with dozens of similar “Venus figurines” found across Paleolithic Europe, conspicuously lacks facial features entirely. Where we might expect eyes, nose, and mouth, we find instead a textured surface suggesting hair or a headdress that completely obscures the face.

This absence of eyes was not an oversight or limitation of early artistic skill. Archaeological evidence suggests Paleolithic peoples were perfectly capable of detailed carving, as demonstrated by the intricate animal figures found in caves like Lascaux and Altamira. The deliberate omission of facial features, particularly eyes, appears to reflect a fundamentally different understanding of human identity and spiritual essence than would emerge in later civilizations.

In Paleolithic culture, individual identity may have been subordinated to broader concepts of fertility, community, and cyclical natural forces. The Venus figurines, with their exaggerated reproductive features and hidden faces, suggest that spiritual power resided in the body’s capacity to create life rather than in individual consciousness or divine vision. The absence of eyes implies that these figures were not meant to see or be seen as individuals, but rather to embody universal principles of fertility and regeneration.

This eyeless tradition persisted in various forms throughout the Neolithic period. Early Anatolian sculptures from Çatalhöyük (7500-5700 BCE) often featured simplified or absent facial features, and many early ceramic traditions across Europe and Asia continued to minimize or eliminate eyes from human representations. The shift toward prominent eyes would mark a revolutionary change in how humans understood their relationship to the divine and their place in the cosmic order.

Mesopotamian Monumentality: The All-Seeing Sacred

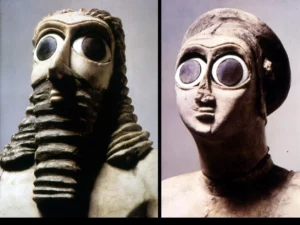

The emergence of complex urban civilization in Mesopotamia around 3500 BCE brought with it a radical transformation in the artistic treatment of human eyes. Sumerian votive statues, designed to be placed in temples as eternal worshippers, featured eyes of almost comical proportions—enormous, wide-open orbs that dominated the face and seemed to stare with unblinking intensity into the divine realm.

The emergence of complex urban civilization in Mesopotamia around 3500 BCE brought with it a radical transformation in the artistic treatment of human eyes. Sumerian votive statues, designed to be placed in temples as eternal worshippers, featured eyes of almost comical proportions—enormous, wide-open orbs that dominated the face and seemed to stare with unblinking intensity into the divine realm.

These oversized eyes were not stylistic accidents but theological statements. In Mesopotamian cosmology, the gods were conceived as anthropomorphic beings who literally watched over human affairs from their celestial realm. The eye became the primary instrument of divine surveillance and judgment, and by extension, the means through which humans could approach and communicate with the gods. Sumerian texts frequently reference the “eye of Enlil” or the “gaze of Marduk,” positioning divine vision as both protective and potentially dangerous.

The technical execution of these eyes reveals sophisticated symbolic thinking. Sumerian sculptors typically inlaid the oversized eye sockets with materials like shell, lapis lazuli, and bitumen to create a startling contrast that made the eyes appear almost luminous. This technique, requiring considerable skill and expensive materials, demonstrates that the prominence of eyes was a deliberate artistic choice backed by significant resources and cultural importance.

Mesopotamian cylinder seals provide additional evidence of the eye’s central role in spiritual and political authority. Royal figures are consistently depicted with large, prominent eyes that seem to gaze directly at the viewer, while supernatural beings like griffins and winged bulls feature multiple eyes or eyes of impossible size. The famous “Eye of Horus” motif, though later adopted by Egyptian culture, may have originated in Mesopotamian concepts of protective divine vision.

The Babylonian creation myth, the Enuma Elish, describes Marduk as having “four eyes” and “four ears,” emphasizing his capacity for cosmic surveillance. This mythological framework positioned sight as the primary means of exercising divine authority, making the prominent eyes of Mesopotamian art not merely decorative but theologically essential.

Egyptian Eternality: The Eye as Soul’s Window

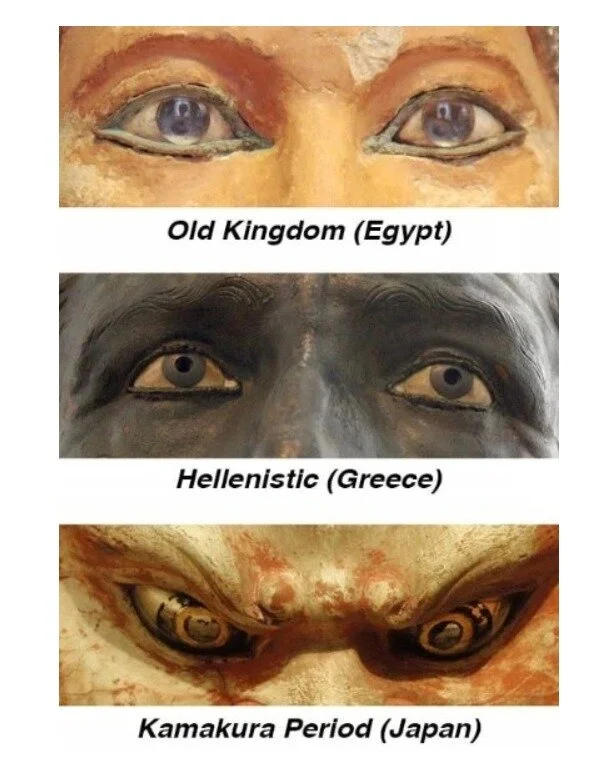

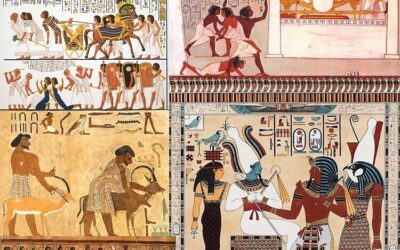

Egyptian civilization developed its own distinctive approach to depicting eyes, one that balanced naturalistic proportion with profound symbolic meaning. Unlike the almost alien enormity of Mesopotamian eyes, Egyptian artistic convention maintained more realistic proportions while investing the eye with complex layers of religious and magical significance.

The Egyptian hieroglyph for “eye” (the wedjat or Eye of Horus) became one of the most powerful protective symbols in ancient art, appearing on everything from royal sarcophagi to common amulets. Egyptian mythology provided a rich narrative framework for understanding the eye’s spiritual significance: the story of Horus losing and recovering his eye in battle with Seth established the eye as a symbol of wholeness, healing, and divine protection.

Egyptian funerary art reveals particularly sophisticated thinking about the relationship between eyes and the soul’s journey after death. Mummy cases featured prominent, carefully painted eyes that were believed to allow the deceased to see in the afterlife. The famous “mummy portraits” of Greco-Roman Egypt show this tradition at its most refined, with haunting, oversized eyes that seem to bridge the gap between life and death.

The technical execution of Egyptian eyes demonstrates remarkable consistency across millennia. The distinctive almond shape, extended with cosmetic lines, and the careful balance between the iris, pupil, and surrounding white remained standard from the Old Kingdom through the Ptolemaic period. This consistency suggests that Egyptian artists were working within a highly developed symbolic system rather than simply following aesthetic preferences.

Egyptian religious texts, particularly the Book of the Dead, are filled with references to vision and seeing in the context of spiritual transformation. The deceased must “see” their way through various challenges in the underworld, and the gods are frequently described in terms of their capacity for sight. Ra, the sun god, was conceived as a cosmic eye that traversed the sky daily, making vision literally synonymous with divine power and the ordering of time itself.

Greek Transformation: From Divine to Human Gaze

The development of Greek art from the Archaic through the Classical periods reveals a gradual but profound shift in how eyes were conceived and depicted. Early Greek kouroi (male sculptures) and korai (female sculptures) featured the distinctive “Archaic smile” and prominent, forward-staring eyes that recall the intensity of Near Eastern traditions. However, Greek artists gradually moved toward more naturalistic proportions and expressions that suggested individual personality rather than generic divine presence.

This transformation reflects broader changes in Greek religious and philosophical thinking. While earlier civilizations had emphasized the eye primarily as an instrument of divine power, Greek culture increasingly explored vision as a means of human knowledge and individual consciousness. The famous Delphic maxim “know thyself” (gnothi seauton) positioned self-awareness, achieved through inner vision, as the highest form of wisdom.

Greek mythology provides numerous examples of the eye’s complex symbolic role. The story of Medusa, whose gaze could turn viewers to stone, suggests anxiety about the potentially dangerous power of vision. The Cyclopes, with their single central eye, represented a kind of focused but limited divine sight. Most significantly, the myth of Argus, the hundred-eyed giant who could never be caught off guard, established the connection between multiple eyes and perfect surveillance that would influence artistic traditions for centuries.

The development of Greek theater further emphasized the importance of the human gaze in expressing emotion and character. Theatrical masks featured prominently displayed eyes that could convey specific emotions to audiences seated far from the stage. This theatrical tradition influenced Greek sculpture, which increasingly sought to capture specific psychological states rather than generic spiritual presence.

Greek philosophical texts, particularly those of Plato, developed sophisticated theories about vision and knowledge that would influence artistic practice. Plato’s allegory of the cave positioned literal sight as a metaphor for intellectual illumination, while his theory of Forms suggested that true vision involved seeing beyond physical appearances to eternal truths. This philosophical framework encouraged artists to use eyes not merely as windows to the divine, but as indicators of the subject’s capacity for wisdom and moral understanding.

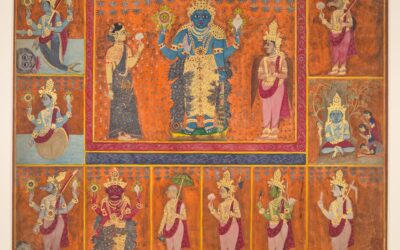

Cross-Cultural Synthesis: Common Patterns and Variations

Despite significant differences in style and execution, ancient cultures share remarkable consistency in treating eyes as sites of spiritual and cosmic significance. Several common patterns emerge across civilizations:

Size and Prominence: From Mesopotamian votive statues to Egyptian mummy portraits to early Greek kouroi, ancient artists consistently made eyes larger and more prominent than naturalistic proportions would suggest. This cross-cultural tendency indicates that oversized eyes served similar symbolic functions across different religious and mythological systems.

Materials and Technique: Cultures that could afford it invested considerable resources in making eyes visually striking through the use of precious materials, careful painting, or intricate inlay work. The technical sophistication required for these effects demonstrates that prominent eyes were not merely artistic conveniences but important cultural priorities.

Divine Association: Across cultures, the most prominent and carefully crafted eyes appear on representations of gods, kings, and other figures associated with divine authority. This pattern suggests a universal association between enhanced vision and spiritual or political power.

Protective Function: Eyes frequently appear as protective symbols, whether in the form of Egyptian wedjat amulets, Mesopotamian guardian figures, or Greek apotropaic masks. This protective function positions the eye as both vulnerable and powerful—capable of being harmed but also capable of warding off harm.

However, significant variations also exist. Mesopotamian eyes tend toward geometric abstraction and almost alien proportions, while Egyptian eyes maintain more naturalistic shapes despite their symbolic elaboration. Greek eyes evolve toward increasingly psychological realism, while maintaining their connection to divine and heroic themes.

These variations reflect different mythological and cosmological frameworks. Mesopotamian religion emphasized the radical otherness of the gods and the need for constant propitiation, leading to eyes that seem to belong to beings from another realm. Egyptian religion focused on the continuity between life and death, producing eyes that appear both human and eternal. Greek religion increasingly emphasized the potential for human achievement and divine-like knowledge, creating eyes that suggest individual personality within cosmic significance.

The Eternal Gaze

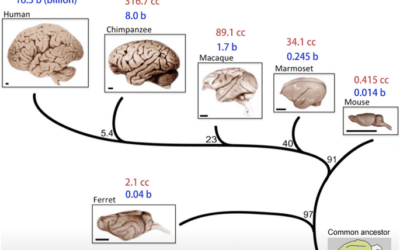

The evolution from the eyeless Venus of Willendorf to the hypnotic stare of ancient temple statues represents one of the most significant developments in human artistic and spiritual expression. This transformation reveals how ancient peoples gradually came to understand individual consciousness, divine authority, and cosmic order as fundamentally visual phenomena.

The prominence of eyes in ancient art was never merely aesthetic. Instead, the careful craftsmanship, expensive materials, and consistent symbolic treatment of eyes across cultures demonstrate that ancient artists were engaged in profound theological and philosophical work. Through their treatment of human vision, they explored questions that remain central to human experience: What is the relationship between sight and knowledge? How do individuals connect with divine power? What is the nature of consciousness and spiritual authority?

The movement from eyeless anonymity to piercing individuality in ancient art parallels the development of complex urban civilizations with their elaborate religious hierarchies, sophisticated mythological systems, and nuanced understanding of human psychology. As societies became more complex, their artistic treatment of eyes became more sophisticated, ultimately producing some of the most powerful and enduring images in human art.

Modern viewers continue to be moved by the intense gaze of ancient statues precisely because these works succeeded in their original purpose: they make visible the invisible realm of spiritual experience and divine encounter. Whether we stand before a Sumerian votive figure, an Egyptian pharaoh, or a Greek kouros, we encounter eyes that seem to look not just at us, but through us toward something eternal and absolute.

In this sense, the ancient understanding of eyes as windows to the soul proves to be more than mere metaphor. Through their artistic treatment of human vision, ancient cultures created works that continue to facilitate encounters with the sacred, the mysterious, and the eternally human. The sacred gaze they crafted in stone, metal, and paint continues to meet our own, bridging millennia and inviting us into the same cosmic questions that occupied our earliest ancestors.

0 Comments