The Sacred Species and Their Archetypal Meanings

In the depths of the human psyche, trees stand as primordial witnesses to our spiritual evolution. They are the axis mundi, the world pillars that connect heaven, earth, and the underworld in virtually every mythological tradition. From a Jungian perspective, trees represent the Self—rooted in the unconscious depths while reaching toward conscious enlightenment. This essay explores ten sacred tree species, examining why specific trees were chosen for particular mythological roles and what their selection reveals about the cultures that venerated them.

1. The Apple and Pomegranate: Eden’s Contested Fruit

The Tree of Knowledge presents our first fascinating case of mythological variation. Western Christianity has long identified the forbidden fruit as an apple (Malus domestica), though the Hebrew Bible simply states “peri” (fruit). This identification likely arose from a Latin pun—”malum” meaning both “apple” and “evil.” The apple’s round form and star-shaped core (when cut horizontally) made it a natural symbol of wholeness and hidden knowledge.

Jewish mystical traditions, particularly in the Kabbalah, often identify the fruit as a pomegranate (Punica granatum). The pomegranate’s numerous seeds—traditionally 613, matching the number of mitzvot—suggest multiplicity within unity. Its crown-like calyx implies sovereignty, while its red juice evokes both life-blood and sacrifice. The pomegranate’s tough exterior hiding sweet complexity mirrors the nature of divine wisdom: difficult to access but infinitely rewarding.

From a depth psychology perspective, both fruits share the quality of containment—they hold seeds, knowledge, potential. The choice between apple and pomegranate may reflect cultural attitudes toward knowledge itself: the apple’s accessibility versus the pomegranate’s complexity.

2. The Bodhi Tree: Ficus religiosa and Enlightenment

Buddha’s enlightenment beneath the Bodhi tree (Ficus religiosa, the sacred fig) was no arbitrary setting. This species, with its heart-shaped leaves that tremble in the slightest breeze, suggests the responsive sensitivity required for awakening. The tree’s extraordinary longevity—specimens can live over 3,000 years—embodies the timelessness of dharma.

The Ficus religiosa’s unique physiology offers profound symbolism: it releases oxygen at night, unlike most trees, suggesting wakefulness in darkness. Its aerial roots grow downward, eventually becoming indistinguishable from the trunk—a perfect metaphor for how enlightenment grows from above (consciousness) to merge with the earthly (material existence).

The choice of this particular fig species over others reflects Buddhism’s emphasis on patient observation. The tree’s leaves, which appear to be in constant meditation-like movement, mirror the mindful awareness central to Buddhist practice.

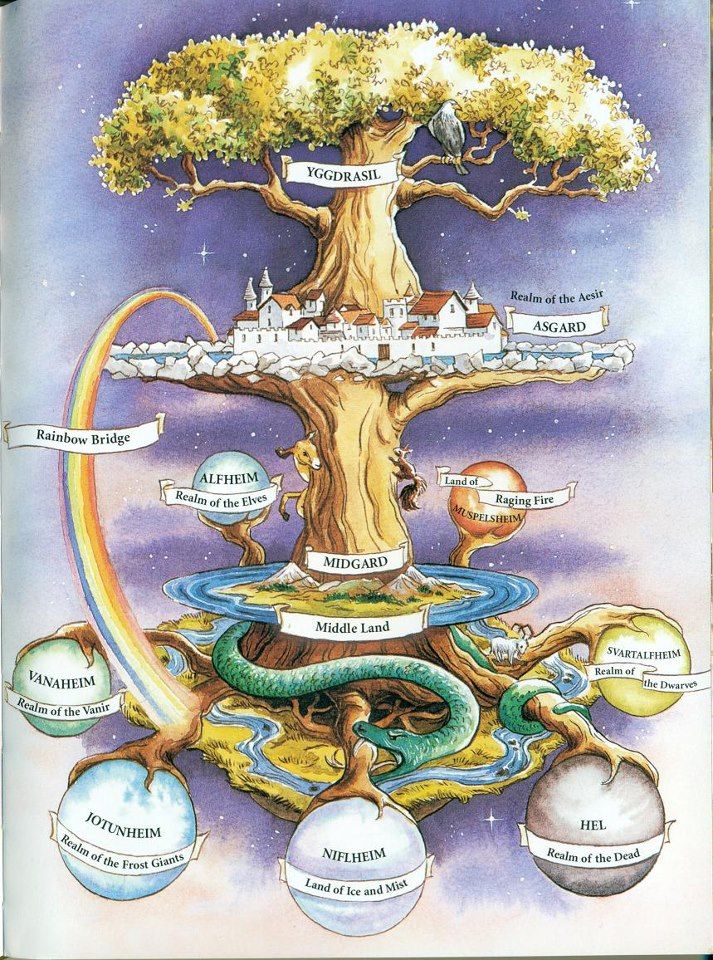

3. Yggdrasil: The Contested World Tree

The species of Yggdrasil, the Norse World Tree, presents one of mythology’s most intriguing botanical mysteries. While the Prose Edda explicitly identifies it as an ash (“Ask Yggdrasil” in Old Norse, Fraxinus excelsior), this identification has sparked considerable scholarly debate.

The traditional ash interpretation has strong support: the European ash grows exceptionally tall and straight, literally reaching toward the heavens. Its compound leaves create a canopy that filters light into dappled patterns—neither full shade nor full sun, embodying the Norse concept of useful ambiguity. The ash’s remarkable flexibility made it the preferred wood for spears and tools, connecting it to both war and craft. Its ability to coppice (regenerate from cut stumps) mirrors the Norse cosmos’s cycle of destruction and rebirth through Ragnarok.

However, compelling alternative theories exist. Some scholars argue for the yew (Taxus baccata), noting that yews were execution trees throughout Northern Europe, fitting Odin’s sacrificial hanging. The yew’s extreme toxicity paired with its incredible longevity (some specimens live 5,000+ years) creates a powerful death-rebirth symbol. The name “Yggdrasil” itself might derive from “yew-pillar” (yggia = yew) rather than from Ygg (Odin’s name).

A third interpretation notes that Yggdrasil is described as “evergreen” in Völuspá, while the European ash is deciduous. This suggests either a different species entirely—perhaps a conifer—or that Yggdrasil transcends earthly botany, existing as an archetypal World Tree beyond species classification. This mythological tree might intentionally combine attributes of multiple sacred trees, creating a composite symbol of cosmic totality.

From a depth psychology perspective, this ambiguity itself carries meaning. The uncertainty forces us to engage with Yggdrasil symbolically rather than literally, approaching it as a psychological reality rather than a botanical specimen.

4. The Oak: Zeus, Thor, and Druids

The oak (Quercus robur and related species) achieved sacred status across Indo-European cultures—from Zeus’s oracle at Dodona to Thor’s sacred groves to the Druids whose name literally means “oak knowledge.” The oak’s selection as the king of trees stems from observable phenomena: it attracts lightning more than any other tree due to its height, its deep taproot that conducts groundwater, and its isolation in fields.

This lightning affinity connected oaks to sky gods across cultures. The tree’s longevity (often 500+ years) and massive girth made it a natural gathering place for councils and justice—hence its association with sovereignty and law. The oak’s production of both food (acorns) and building material embodied the dual role of divine providence and structure.

From a Jungian view, the oak represents the senex archetype—the wise old king, established authority, enduring tradition. Its deciduous nature, dropping leaves while maintaining structure, suggests how wisdom discards the unnecessary while preserving essential form.

5. The Willow: Feminine Mysteries

The willow (Salix species) appears in mythologies worldwide as a tree of feminine power, magic, and lunar associations. In Greek mythology, it was sacred to Hecate and Persephone. Celtic traditions associated it with the goddess Brigid. Chinese mythology links willows to immortality and feminine grace.

The willow’s preference for watery environments connects it to the emotional and unconscious realms. Its drooping branches suggest grief (hence “weeping willow”) but also concealment and protection. The tree’s remarkable ability to root from any fallen branch represents regeneration through emotional processing—a key concept in depth psychology.

Significantly, willow bark contains salicin, the precursor to aspirin. Ancient peoples’ discovery of its pain-relieving properties likely reinforced its association with healing through emotional release. The willow thus embodies the therapeutic principle that engaging with sorrow can lead to healing.

6. The Cedar: Divine Architecture

The cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) holds unique status as the building material of sacred spaces—from Solomon’s Temple to Sumerian temples. Its selection reflects practical and symbolic factors: the wood’s aromatic oils make it naturally resistant to rot and insects, suggesting incorruptibility. Its straight grain and workability made it ideal for precise sacred geometry.

The cedar’s pyramid-shaped crown and evergreen nature suggested eternal aspiration toward divinity. Its ability to grow at high altitudes, closer to the heavens, reinforced its role as mediator between realms. The tree’s aromatic resin was used in mummification and temple incense, literally preserving the sacred and making it sensually present.

In Jungian terms, the cedar represents the templum—the sacred space within the psyche where transformation occurs. Its use in construction suggests how we build our inner sacred spaces from materials that resist psychological decay.

7. The Olive: Peace and Persistence

The olive tree (Olea europaea) earned sacred status through its remarkable persistence and productivity. Trees can live over 2,000 years and regenerate from seemingly dead stumps. This regenerative power made it a natural symbol of peace after conflict—hence the olive branch.

Athena’s gift of the olive to Athens reveals its civilizational importance: the tree provides food, oil for light, medicine, and wood. It thrives in rocky, challenging soil, suggesting wisdom arising from adversity. The olive’s small, tough leaves minimize water loss, embodying the conservation of energy that wisdom requires.

The extensive processing required to make olives edible—curing to remove bitterness—parallels the psychological work needed to transform raw experience into wisdom. The olive thus represents earned peace, not mere absence of conflict.

8. The Sycamore Fig: Egyptian Afterlife

In Egyptian mythology, the sycamore fig (Ficus sycomorus) was the tree of life and death, associated with Hathor and Nut. Coffins were made from its wood, and the deceased were said to be nourished by sycamore figs in the afterlife. This tree’s selection reveals sophisticated symbolic thinking: it produces fruit year-round in Egypt’s climate, suggesting eternal sustenance.

The sycamore fig’s unique pollination relationship with wasps, where the wasp must die inside the fruit for it to ripen, creates a profound death-rebirth symbol. The tree’s milky sap, reminiscent of mother’s milk, reinforced its nurturing associations. Its broad canopy provided rare shade in the desert, making it a natural gathering place for both the living and, mythologically, the dead.

9. The Hawthorn: Fairy Thresholds

In Celtic and British folklore, the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) marks boundaries between worlds. Solitary hawthorns, especially those growing from ancient burial mounds, were considered fairy trees, not to be disturbed. The tree’s biology supports its liminal reputation: it flowers in May (Beltane), marking the transition to summer, yet its flowers smell of death (trimethylamine, also produced by decaying tissue).

The hawthorn’s vicious thorns and beautiful flowers embody the fairy realm’s dual nature—beautiful but dangerous. Its dense, twisted growth pattern creates natural hiding places, reinforcing associations with the hidden world. Medicinally, hawthorn treats heart conditions, connecting it to matters of courage and love—both requiring one to cross thresholds.

10. The Pine: Eternal Life and Sacrifice

The pine (Pinus species) appears in numerous traditions as a symbol of immortality and sacrifice. In Greco-Roman mythology, the pine was sacred to Cybele and Attis, whose death and resurrection were celebrated with pine trees. In East Asian traditions, pines represent longevity and steadfast virtue.

The pine’s evergreen nature obviously suggests eternal life, but its resin—amber when fossilized—literally preserves life forms for millions of years. Pine cones, with their spiral patterns following the Fibonacci sequence, embody sacred geometry. The pine’s ability to grow in poor soil and harsh climates represents spiritual persistence through adversity.

The Wood of the Cross: Speculative Traditions

Christian tradition offers various identifications for the wood of the Cross, each carrying symbolic weight. Some traditions claim cedar, linking Christ’s sacrifice to Temple worship. Others suggest oak, connecting to strength and endurance. Medieval legend claimed the Cross was made from the Tree of Knowledge itself, creating a profound redemption narrative.

In Mithraism, though less documented, sacred poles and crosses were likely made from pine, connecting to Attis mythology and resurrection themes. The speculation itself reveals how cultures project meaning onto materials, seeking cosmic significance in earthly elements.

The Forest of the Collective Unconscious

These ten sacred trees form a forest in the collective unconscious, each species carrying specific archetypal energies. Their selection was never arbitrary but arose from careful observation of their properties—physical, medicinal, and phenomenological. Trees that attracted lightning became associated with sky gods. Trees that regenerated connected to resurrection. Trees with complex fruits suggested hidden wisdom.

From a Jungian perspective, our ancestors’ tree choices reveal sophisticated psychological understanding. They recognized that different tree species could serve as vessels for different aspects of the numinous. The specificity of these associations—why this tree and not another—demonstrates humanity’s deep need to find meaning in the natural world and to use that meaning for psychological and spiritual development.

In our modern disconnection from nature, we risk losing these nuanced relationships with the more-than-human world. Yet the archetypal power of these trees persists in our dreams, our literature, and our remaining fragments of folk wisdom. By understanding why specific trees were chosen for specific sacred roles, we can better understand both our ancestors’ wisdom and our own deep psychological needs.

The holy wood—the sacred forest—remains standing in the collective unconscious, waiting for those who seek its shade and sustenance. Each tree offers its unique medicine: the apple’s knowledge, the bodhi’s awakening, the oak’s strength, the willow’s healing. In recognizing these offerings, we recognize parts of ourselves, for we too are part of this eternal forest, rooted in earth while reaching toward meaning.

0 Comments