What did Prehistoric Religion Look Like:

Main Ideas and Key Points:

The Venus of Willendorf, a Paleolithic figurine, suggests the existence of prehistoric “Venus cults” that venerated female deities associated with fertility and the earth.

Prehistoric religions likely involved myth and ritual to explain the world, provide meaning, and promote social bonding. Shamanism, involving altered states of consciousness, may have been an early form of religious practice.

The Neolithic Revolution saw the rise of agriculture, settled communities, and more complex religions centered around ancestor worship, fertility cults, and the construction of megalithic structures.

The Axial Age (800-200 BCE) gave rise to major religious and philosophical traditions that emphasized individual salvation, inner transformation, and universal truths.

Psychedelic experiences and altered states of consciousness may have played a role in prehistoric and ancient religions. The fields of neurotheology and psychedelic epistemology study the neural basis of religious experiences.

Evolutionary psychology and cognitive science of religion offer explanations for the origins of religious belief, such as the hyperactive agency detection device (HADD) and minimally counterintuitive concepts. Religion may have evolved to promote cooperation and group survival.

Chimpanzees and bonobos exhibit behaviors that resemble human ritual and spirituality, such as grieving, empathy, and a sense of fairness. Whales also possess complex social and emotional capacities.

The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture of Siberia (24,000-15,000 years ago) provides early evidence of symbolic thought, ritual behavior, and mythology that may have influenced later religious traditions through migration and cultural diffusion.

Sacred landscapes, such as mountains, caves, and springs, were imbued with spiritual significance in prehistoric times and shaped the development of religious practices and beliefs.

Ancestor worship emerged as an important aspect of prehistoric religion, as evidenced by burial practices and the construction of megalithic tombs.

Art and symbolism, such as the use of red ochre and the creation of Venus figurines, played a crucial role in prehistoric religious expression and ritual.

Studying prehistoric religion requires an interdisciplinary approach, combining archaeology, anthropology, genetics, linguistics, and cognitive science to uncover the complex origins and evolution of human spirituality.

The Venus of Willendorf:

In the hit HBO series “The Young Pope,” the enigmatic and unconventional Pope Pius XIII, played by Jude Law, is seen contemplating a replica of the Venus of Willendorf on his desk. While the show never explicitly addresses the figurine’s significance, its presence serves as a subtle nod to the enduring power and mystery of this ancient fertility symbol.

In the hit HBO series “The Young Pope,” the enigmatic and unconventional Pope Pius XIII, played by Jude Law, is seen contemplating a replica of the Venus of Willendorf on his desk. While the show never explicitly addresses the figurine’s significance, its presence serves as a subtle nod to the enduring power and mystery of this ancient fertility symbol.

The Venus of Willendorf, discovered in Austria in 1908, is one of the most well-known examples of Paleolithic art. Dating back to around 25,000 years ago, this small limestone figurine, measuring just over 4 inches in height, depicts a voluptuous female form with exaggerated breasts, belly, and hips. The figure’s head is covered in what appears to be a braided hairstyle or headdress, and her face is devoid of detail.

Theories about the Venus Cults:

The Venus of Willendorf is part of a larger group of Paleolithic figurines known as “Venus figurines,” found across Europe and Eurasia. These figurines, often characterized by their emphasis on female reproductive features, have led to theories about the existence of widespread “Venus cults” in prehistoric societies.

One theory suggests that these figurines served as fertility talismans, used in rituals to promote successful childbearing and ensure the survival of the community. The exaggerated physical attributes of the Venus figurines may have symbolized abundance, nourishment, and the life-giving power of the female body.

Another theory proposes that the Venus figurines represented mother goddesses or female deities associated with the earth, nature, and the cycle of birth, death, and regeneration. The worship of these powerful female figures may have provided a sense of comfort, protection, and connection to the sacred feminine principle.

Psychological Function:

From a psychological perspective, the Venus cults and their associated figurines may have served several important functions. Firstly, they provided a tangible representation of the mysterious forces of life, fertility, and creation, allowing prehistoric humans to engage with these concepts on a symbolic level.

Secondly, the veneration of the female form and its life-giving properties may have helped to counterbalance the uncertainties and challenges of prehistoric life. By focusing on the power and resilience of the female body, these ancient societies could find hope and reassurance in the face of hardship.

Finally, the Venus cults may have played a role in the psychological and social development of prehistoric communities. The shared veneration of female deities and participation in related rituals could have fostered a sense of unity, belonging, and purpose among group members, strengthening social bonds and promoting cooperation.

The Significance of the Venus of Willendorf:

As one of the earliest and most iconic examples of prehistoric art, the Venus of Willendorf holds a special place in our understanding of human cultural evolution. Its striking form and mysterious origins have captivated the imaginations of scholars and laypeople alike for over a century.

The Venus of Willendorf serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring human fascination with fertility, creation, and the sacred feminine. Its presence in modern popular culture, such as its appearance in “The Young Pope,” demonstrates the ongoing relevance and resonance of these ancient symbols in our collective psyche.

As we continue to study and interpret the Venus of Willendorf and other Paleolithic figurines, we gain valuable insights into the beliefs, practices, and psychological landscape of our prehistoric ancestors. These ancient fertility symbols offer a glimpse into the timeless human quest for meaning, connection, and the celebration of the life-giving power of the feminine.

What is Religion Anyway?

The Role of Myth in Prehistoric Religion:

Myths played a crucial role in the religious beliefs and practices of prehistoric societies. These narratives served to explain the origins of the world, the nature of the divine, and the place of humans in the cosmos. Myths often featured archetypal characters and themes, such as the hero’s journey, the creation of the world, and the struggle between good and evil.

One of the key functions of myth was to provide a sense of meaning and purpose in the face of the mysteries and challenges of existence. By situating the individual within a larger narrative framework, myths helped to create a sense of identity and belonging, and to provide guidance for navigating the complexities of life.

Myths were also closely tied to ritual practices, serving as the basis for religious ceremonies and enactments. Through the performance of mythic narratives, individuals could participate in the sacred events of the past and connect with the divine realm.

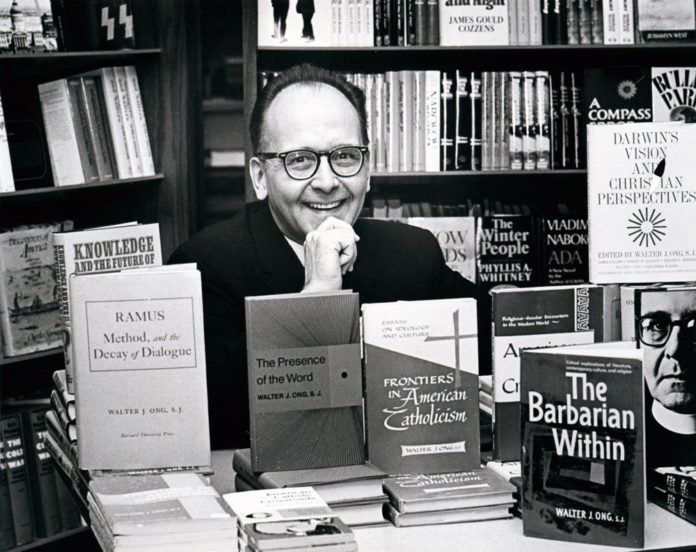

The study of comparative mythology, as pioneered by scholars such as Joseph Campbell and Mircea Eliade, has revealed striking similarities in the mythic traditions of cultures around the world. This has led some to propose the existence of universal archetypes and patterns that reflect the common experiences and concerns of human beings across time and space.

However, it is important to recognize the diversity and specificity of mythic traditions, and to avoid reducing them to a single, monolithic framework. Each culture has its own unique set of myths and stories, shaped by its particular history, environment, and social structure.

The Paleolithic Origins of Shamanism:

Shamanism is one of the oldest and most widespread religious traditions, found in cultures across the world. The origins of shamanism can be traced back to the Paleolithic era, where evidence suggests the presence of ritualistic practices and beliefs related to communication with the spirit world.

The term “shaman” comes from the Tungus language of Siberia, where it refers to a spiritual practitioner who enters altered states of consciousness to interact with the spirit world on behalf of their community. Shamans are believed to have the ability to heal the sick, communicate with ancestors and spirits, and navigate the realms of the dead.

The earliest evidence of shamanic practices comes from the Upper Paleolithic period, around 30,000 years ago. Cave paintings from this era depict human figures in animal costumes, often in a trance-like state, suggesting the presence of shamanic rituals.

One of the key features of shamanism is the use of ecstatic techniques, such as drumming, chanting, and the use of psychoactive substances, to induce altered states of consciousness. These practices are believed to allow the shaman to enter the spirit world and communicate with supernatural entities.

Shamanism is also closely tied to the natural world, with animals and plants playing a central role in shamanic cosmologies. Shamans often have animal spirit guides or helpers, and may use animal parts in their rituals and healing practices.

The spread of shamanism from its Paleolithic origins can be traced through the migration of human populations across the world. As people moved into new environments and adapted to new challenges, shamanic practices evolved and diversified, giving rise to a wide range of regional and cultural variations.

Today, shamanism continues to be practiced by indigenous communities around the world, and has also been adopted and adapted by Western spiritual seekers. The study of shamanism has provided valuable insights into the nature of consciousness, the relationship between humans and the natural world, and the role of ritual and spirituality in human life.

The Neolithic Revolution and the Rise of Complex Religions:

The Neolithic Revolution, which began around 12,000 years ago, marked a major transition in human history, as people shifted from a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled agricultural communities. This transformation had profound implications for the development of religion, as the rise of complex societies and specialized labor created new opportunities and challenges for religious belief and practice.

One of the key features of the Neolithic Revolution was the emergence of large-scale, permanent settlements, such as the city of Çatalhöyük in Turkey, which had a population of up to 10,000 people. These settlements required new forms of social organization and leadership, and religion played a crucial role in legitimizing and maintaining these structures.

The rise of agriculture also led to the development of new religious beliefs and practices centered around the cycles of nature and the fertility of the land. The worship of mother goddesses and agricultural deities became widespread, as people sought to ensure the success of their crops and the continuity of their communities.

The Neolithic period also saw the emergence of specialized religious roles, such as priests and temple administrators, who were responsible for overseeing religious ceremonies and maintaining sacred sites. The construction of large-scale religious monuments, such as the megalithic temples of Malta and the stone circles of Britain, reflects the increasing complexity and sophistication of religious practice during this time.

The development of writing and record-keeping during the Neolithic period also had important implications for religion, allowing for the codification and transmission of religious beliefs and practices. The earliest known religious texts, such as the Sumerian Kesh Temple Hymn and the Egyptian Pyramid Texts, date back to this period.

However, the Neolithic Revolution also brought new challenges and tensions to the development of religion. The rise of social stratification and inequality led to the emergence of competing religious ideologies and the use of religion as a tool of social control. The spread of infectious diseases in densely populated settlements also gave rise to new forms of religious practice centered around healing and the prevention of illness.

The legacy of the Neolithic Revolution continues to shape the development of religion to this day, as the complex societies and belief systems that emerged during this period laid the foundations for the world’s major religious traditions. The study of Neolithic religion provides valuable insights into the ways in which social, economic, and environmental factors interact with religious beliefs and practices, and the enduring influence of this period on the evolution of human spirituality.

The Axial Age and the Emergence of Universalizing Religions:

The Axial Age, which lasted from approximately 800 BCE to 200 BCE, was a period of remarkable religious and philosophical ferment, during which many of the world’s major religious and ethical traditions emerged. This period saw the rise of universalizing religions, which sought to transcend local and ethnic boundaries and offer a message of salvation and enlightenment to all of humanity.

The term “Axial Age” was coined by the philosopher Karl Jaspers, who argued that during this period, there was a fundamental shift in human consciousness, as people began to question the traditional beliefs and values of their societies and seek new forms of spiritual and moral guidance. This shift was driven by a range of factors, including the rise of large-scale empires, the growth of trade and cultural exchange, and the emergence of new intellectual and philosophical movements.

Some of the key figures and movements that emerged during the Axial Age include:

- The Buddha (c. 563-483 BCE), who founded Buddhism and taught the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path as a way to end suffering and achieve enlightenment.

- Confucius (551-479 BCE), who developed a system of ethical and political philosophy based on the principles of hierarchy, harmony, and the cultivation of virtue.

- The Hebrew prophets, such as Isaiah and Jeremiah, who criticized the corruption and injustice of their society and called for a return to the worship of Yahweh and the practice of social justice.

- The Greek philosophers, such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, who developed new methods of rational inquiry and sought to understand the nature of reality, ethics, and the human condition.

- Zoroaster (c. 1500-1000 BCE), who founded Zoroastrianism and taught the existence of a supreme god, Ahura Mazda, and the cosmic struggle between good and evil.

These movements shared a number of common features, including a focus on individual salvation and the cultivation of moral and spiritual virtues, a critique of traditional social and religious institutions, and a belief in the unity and transcendence of the divine. They also emphasized the importance of personal responsibility and the need for individuals to seek their own path to enlightenment and liberation.

The legacy of the Axial Age continues to shape the development of religion and philosophy to this day, as the ideas and values that emerged during this period have had a profound influence on the world’s major religious and ethical traditions. The study of the Axial Age provides valuable insights into the ways in which religious and philosophical ideas evolve and spread across cultures, and the enduring impact of these ideas on human society and thought.

Neurotheology of Religious Experience:

The use of psychoactive substances in religious and spiritual contexts has a long and complex history, dating back to ancient shamanic traditions and the mystery cults of the Greco-Roman world. In recent years, however, the study of psychedelic experiences has emerged as a new and exciting field of inquiry, known as psychedelic epistemology and neurotheology.

Neurotheology is the study of the neural basis of religious and spiritual experiences. This field uses brain imaging techniques, such as fMRI and EEG, to explore the neural correlates of meditation, prayer, and other spiritual practices. Researchers in this field have identified a number of brain regions and networks that are involved in religious and spiritual experiences, including the prefrontal cortex, the limbic system, and the default mode network.

One of the key insights of neurotheology is that religious and spiritual experiences are not simply “in the head,” but are deeply embodied and involve complex interactions between the brain, the body, and the environment. For example, studies have shown that meditation can lead to changes in brain structure and function, as well as improvements in immune function, cardiovascular health, and overall well-being.

Another insight of neurotheology is that religious and spiritual experiences are not necessarily unique or sui generis, but may involve similar neural processes to other forms of intense emotional and cognitive experience, such as love, awe, and flow states. This suggests that there may be common neural mechanisms underlying a wide range of human experiences, and that the study of religion and spirituality can provide valuable insights into the nature of the mind and the human condition.

The fields of psychedelic epistemology and neurotheology are still in their early stages, and there is much work to be done to fully understand the complex relationship between psychedelics, consciousness, and religious experience. However, these emerging fields offer exciting new perspectives on the nature of the mind and the role of religion and spirituality in human life, and have the potential to transform our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

The Evolutionary Theories of Religion:

One of the most influential approaches to understanding the origins of religion is the evolutionary perspective, which seeks to explain religious beliefs and practices in terms of their adaptive value for human survival and reproduction. According to this view, religion emerged as a way of promoting social cohesion, cooperation, and moral behavior among early human groups, thereby increasing their chances of survival in a harsh and unpredictable environment.

One of the key proponents of this view is the evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson, who has argued that religion can be understood as a form of “group-level adaptation” that helps to promote the fitness of the group as a whole, even if it may come at a cost to individual members. For example, religious beliefs and practices that encourage altruism, self-sacrifice, and loyalty to the group may have helped to ensure the survival of early human societies in the face of external threats and internal conflicts.

Another evolutionary theory of religion is the “costly signaling” hypothesis, which suggests that religious practices serve as a way of demonstrating commitment and loyalty to the group. According to this view, engaging in costly and time-consuming religious rituals is a way of signaling to others that one is a reliable and trustworthy member of the community, thereby increasing one’s chances of forming alliances and securing access to resources.

The Cognitive Theories of Religion:

While the evolutionary theories focus on the adaptive value of religion for human survival and reproduction, cognitive theories seek to explain the origins of religious beliefs in terms of the underlying mental processes that give rise to them. One of the most influential cognitive theories of religion is the “hyperactive agency detection device” (HADD) hypothesis, which suggests that humans have a natural tendency to attribute agency and intentionality to the world around them, even in the absence of clear evidence for such agency.

According to this view, the HADD is a byproduct of the evolution of human cognition, which has been shaped by the need to detect and respond to potential threats in the environment. In the case of religion, the HADD may lead people to attribute agency and intentionality to natural phenomena, such as storms, earthquakes, and disease, as well as to imagine the existence of supernatural agents, such as gods and spirits, who are responsible for these events.

Another cognitive theory of religion is the “minimally counterintuitive” hypothesis, which suggests that religious beliefs are particularly memorable and transmissible because they involve a balance between intuitive and counterintuitive elements. According to this view, religious concepts that are too intuitive (e.g., a tree that grows leaves) or too counterintuitive (e.g., a tree that speaks fluent French) are less likely to be remembered and passed on than those that strike a balance between the two (e.g., a tree that can hear people’s prayers).

The Neurological Theories of Religion:

In recent years, advances in neuroscience have led to the development of new theories about the origins and functions of religion based on the study of the brain. One of the most intriguing of these theories is the idea that religion may be a spandrel, or a byproduct of other cognitive and emotional processes that have evolved for different purposes.

According to this view, the experience of religious or mystical states may arise from the interaction between different parts of the brain, such as the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in higher-order cognitive functions like planning and decision-making, and the subcortical regions of the brainstem, which are involved in more primitive emotional and instinctual responses.

For example, some researchers have suggested that the experience of religious ecstasy or transcendence may be the result of a temporary “deafferentation” or disconnection between the prefrontal cortex and the brainstem, allowing the more primitive and emotionally-charged regions of the brain to take over. This could explain why many religious experiences are characterized by feelings of unity, dissolution of the self, and a sense of connection to something greater than oneself.

Another neurological theory of religion is the “God spot” hypothesis, which suggests that there may be specific regions of the brain that are involved in the experience of religious or spiritual states. For example, some studies have found that the temporal lobes, which are involved in the processing of language and emotion, are particularly active during religious experiences, while others have identified the parietal lobes, which are involved in the sense of self and body awareness, as being important for the experience of meditation and prayer.

Other Theories of Religion:

Terror Management Theory:

This theory, based on the work of Ernest Becker, suggests that religion serves as a way for humans to cope with the fear and anxiety caused by the awareness of death. According to this view, religious beliefs and practices provide a sense of meaning and purpose in life, as well as the promise of literal or symbolic immortality, which helps to alleviate the terror of death.

Attachment Theory:

This theory, originally developed by John Bowlby to explain infant-caregiver relationships, has been applied to the study of religion by scholars such as Lee Kirkpatrick. According to this view, religious beliefs and practices serve as a form of attachment, providing a sense of security and comfort in times of stress or uncertainty. God or other supernatural agents may be seen as attachment figures, providing a safe haven and a secure base for individuals.

Moral Foundations Theory: This theory, developed by Jonathan Haidt and others, suggests that religion is closely tied to moral intuitions and values. According to this view, religious beliefs and practices are shaped by innate moral foundations, such as care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. Different religions may emphasize different moral foundations, but all serve to regulate moral behavior and promote social cohesion.

Dual Inheritance Theory:

This theory, proposed by Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson, suggests that religion is a product of both genetic and cultural evolution. According to this view, religious beliefs and practices are shaped by both innate cognitive biases and learned cultural traditions. Over time, religions that are more successful at promoting group survival and reproduction are more likely to be passed on to future generations, leading to the evolution of increasingly complex and adaptive forms of religion.

Meaning Maintenance Model:

This theory, developed by Steven Heine and others, suggests that religion serves as a way for individuals to maintain a sense of meaning and coherence in the face of uncertainty or anomaly. According to this view, when individuals encounter events or experiences that threaten their sense of meaning (e.g., death, suffering, injustice), they may turn to religious beliefs and practices as a way of restoring a sense of order and purpose. Religion provides a framework for making sense of the world and one’s place in it, thereby reducing feelings of anxiety and uncertainty.

Compensator Theory:

Developed by Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge, this theory suggests that religion serves as a form of compensation for rewards that are scarce or unavailable in the real world. According to this view, religious beliefs and practices offer “compensators” (e.g., promises of afterlife, divine justice) that provide a sense of hope and consolation in the face of deprivation or suffering. This theory is often used to explain the appeal of religion among marginalized or disadvantaged groups.

Costly Signaling Theory:

This theory, which is related to the evolutionary theories mentioned in the passage, suggests that religious practices serve as a form of costly signaling, demonstrating an individual’s commitment to the group. By engaging in costly and time-consuming religious rituals, individuals can signal their loyalty and trustworthiness to others, thereby increasing their chances of social cooperation and support. This theory has been used to explain the persistence of seemingly irrational or counterproductive religious practices.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory:

Developed by Leon Festinger, this theory suggests that religion may serve as a way of reducing cognitive dissonance, or the psychological discomfort caused by holding contradictory beliefs or values. According to this view, when individuals encounter information that challenges their existing beliefs (e.g., the problem of evil), they may turn to religious explanations or rationalizations as a way of reducing dissonance and maintaining a sense of cognitive consistency.

Ritual Theory:

This theory, which has been developed by anthropologists such as Roy Rappaport and Victor Turner, suggests that religious rituals serve important social and psychological functions. According to this view, rituals provide a way of creating a sense of social solidarity, reinforcing group norms and values, and facilitating individual transformation and growth. Rituals may also serve as a form of communication, conveying important messages and meanings through symbolic action.

Existential Theory:

This theory, which draws on the work of existential philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard and Jean-Paul Sartre, suggests that religion serves as a way of coping with the existential anxieties and challenges of human life. According to this view, religious beliefs and practices provide a sense of meaning and purpose in the face of the absurdity and finitude of existence. Religion may also offer a way of transcending the limitations of the self and connecting with something greater, such as God or the universe.

Pre-human and Non Human Religious Behavior:

To understand the origins of human religious behavior, it is useful to examine the traits exhibited by our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos. While these primates do not practice religion in the human sense, they possess certain characteristics that may have been necessary for the evolution of religion, such as high intelligence, symbolic communication, social norms, and a sense of self-continuity. Additionally, other animals, such as elephants, have been observed performing ritualistic behaviors for their dead, suggesting that the capacity for religious-like behavior may not be unique to humans.

The Origins of Religious Behavior in Pre-Human Hominids:

While the earliest unequivocal evidence of religious behavior in humans dates back to the Middle Paleolithic era, there are indications that the cognitive and cultural foundations of religion may have emerged in earlier hominid species. Several pre-human hominids have shown signs of behavior that could be interpreted as precursors to religious or ritualistic practices, such as the appreciation of aesthetics, the creation of non-utilitarian objects, and the engagement in repetitive, patterned activities.

Homo heidelbergensis (600,000 to 200,000 years ago):

Homo heidelbergensis, an ancestor of both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, displayed some of the earliest evidence of potential ritualistic behavior. At the Sima de los Huesos site in Spain, researchers discovered a pit containing the remains of at least 28 individuals, along with a single red quartzite hand axe. The deliberate placement of these remains and the inclusion of a distinctive, symmetrical tool suggests that H. heidelbergensis may have engaged in intentional burial practices and recognized the symbolic significance of certain objects.

Homo erectus (1.9 million to 143,000 years ago):

Homo erectus, a species that emerged in Africa and later spread throughout Europe and Asia, may have exhibited early signs of aesthetic appreciation and symbolic thinking. Some H. erectus sites have yielded symmetrical, carefully crafted hand axes that appear to have been made for non-utilitarian purposes. These artifacts, known as “Acheulean hand axes,” may have served as a form of artistic expression or as markers of social identity, indicating a growing capacity for symbolic thought and potentially laying the groundwork for the development of religious beliefs.

Homo naledi (335,000 to 236,000 years ago):

Homo naledi, a species discovered in South Africa in 2013, has been associated with the deliberate disposal of the dead. The remains of at least 15 individuals were found in the Dinaledi Chamber of the Rising Star Cave system, a site that would have been difficult to access and was not inhabited by H. naledi. This suggests that the species may have intentionally placed their dead in this remote location, possibly as part of a ritualistic or symbolic practice.

Neanderthals (400,000 to 40,000 years ago):

Neanderthals, a sister species to Homo sapiens, have been associated with several behaviors that could be interpreted as early signs of religious or ritualistic practices. Some Neanderthal burials, such as those found at Shanidar Cave in Iraq and La Ferrassie in France, included grave goods like flowers, tools, and animal bones, suggesting a belief in an afterlife or a desire to provide for the deceased in the next world. Additionally, Neanderthal sites have yielded evidence of the use of pigments like red ochre, which may have been used for symbolic or ceremonial purposes, as well as the creation of ornaments and the possible use of feathers for decorative purposes.

The Role of Music and Dance in Prehistoric Religious Rituals

Music and dance have been integral components of human religious ceremonies since prehistoric times. Archaeological evidence, such as the discovery of ancient musical instruments and depictions of dancing figures in prehistoric art, suggests that these practices played a crucial role in the spiritual lives of our ancestors.

One of the primary functions of music and dance in prehistoric religious rituals was to facilitate group cohesion. Engaging in synchronized movements and rhythms fostered a sense of unity and shared purpose among participants, strengthening social bonds and promoting cooperation. This was particularly important in ancient societies, where survival often depended on the ability of individuals to work together effectively.

Moreover, music and dance were likely used to induce altered states of consciousness, which were believed to facilitate communication with the spiritual world. The repetitive, rhythmic nature of these practices, combined with the use of psychoactive substances in some cases, could have helped participants enter trance-like states, enabling them to access hidden realms of knowledge and connect with ancestral spirits or deities.

The trance-inducing potential of music and dance in prehistoric rituals is exemplified by the “Lion Man,” a unique Paleolithic figurine discovered in Germany’s Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave. This enigmatic sculpture, which depicts a human figure with a lion’s head, has been interpreted as a representation of a shaman in a trance state, possibly achieved through the use of music, dance, and other ritualistic practices.

Prehistoric musical instruments, such as bone flutes, drums, and rattles, further attest to the importance of music in ancient religious ceremonies. The hauntingly beautiful melodies produced by these instruments may have been seen as a means of summoning spirits, appeasing deities, or facilitating the passage of the deceased into the afterlife.

Similarly, the elaborate costumes and masks worn by dancers in prehistoric rituals, as depicted in rock art and figurines, suggest that dance was not merely a form of entertainment but a sacred act imbued with deep spiritual significance. The rhythmic movements of the dancers may have been believed to channel the power of the gods, ensuring the prosperity and well-being of the community.

As prehistoric societies developed more complex forms of social organization, music and dance likely played an increasingly important role in religious ceremonies. The construction of large-scale ritual structures, such as the megalithic temples of Malta and the stone circles of Britain, would have required the coordination of significant numbers of people, and music and dance may have been used to synchronize their efforts and foster a sense of shared purpose.

The Significance of Sacred Landscapes in Prehistoric Religion

In prehistoric times, natural features such as mountains, caves, springs, and rivers were not merely seen as passive elements of the environment but as sacred spaces imbued with spiritual significance. These landscapes played a crucial role in the religious beliefs and practices of ancient societies, serving as sites for rituals, offerings, and pilgrimages.

Mountains, for example, were often regarded as the dwelling places of gods, ancestors, or other powerful spiritual entities. The imposing presence and awe-inspiring beauty of these natural features may have evoked a sense of the divine, leading prehistoric people to seek closer communion with the sacred through pilgrimage and ritual. The ancient Andean site of Machu Picchu, perched high in the Peruvian Andes, is a testament to the enduring spiritual significance of mountain landscapes in prehistoric religion.

Similarly, caves were often seen as portals to the underworld or the realm of the spirits. The dark, mysterious depths of these subterranean spaces may have been believed to hold powerful transformative energies, making them ideal sites for initiation rites, shamanic journeys, and other spiritual practices. The Paleolithic cave art of Lascaux and Chauvet in France, with their stunning depictions of animals and enigmatic symbols, hints at the profound spiritual significance of these underground sanctuaries.

Springs and other water sources were also imbued with sacred meaning in prehistoric religious traditions. The life-giving properties of water, essential for the survival of both humans and the natural world, may have been seen as a manifestation of divine generosity and abundance. Many ancient societies performed rituals and made offerings at springs, wells, and rivers to honor the spirits of these watery places and ensure the continued flow of their blessings.

The spiritual significance of sacred landscapes in prehistoric religion is further evidenced by the construction of megalithic monuments and other ritual structures in close proximity to these natural features. Stonehenge, for example, is aligned with the summer solstice sunrise and the winter solstice sunset, suggesting a deep connection between this ancient stone circle and the cycles of the sun and the seasons. Similarly, the Neolithic stone circles of Avebury and the Orkney Islands in Britain are situated near sacred springs and other water sources, highlighting the interplay between the built and natural environments in prehistoric spiritual practices.

As prehistoric societies developed more complex forms of social organization and religious belief, the significance of sacred landscapes may have taken on new dimensions. The construction of large-scale ritual centers, such as the Mesopotamian ziggurats and the Egyptian pyramids, could be seen as attempts to recreate the sacred geography of the cosmos in miniature, with these towering structures serving as axis mundi or “world centers” that connected the earthly and celestial realms.

The Emergence of Ancestor Worship in Prehistoric Societies

Ancestor worship, the practice of honoring and venerating the spirits of the dead, has been a central feature of many prehistoric societies around the world. The archaeological record provides compelling evidence for the emergence of ancestor worship practices in ancient cultures, as seen in the treatment of the dead and the creation of elaborate burial mounds and megalithic structures.

One of the earliest indications of ancestor worship can be found in the Paleolithic burials of Homo sapiens, which often included grave goods such as tools, ornaments, and animal remains. The careful positioning of the bodies and the inclusion of these offerings suggests a belief in an afterlife and a desire to provide for the needs of the deceased in the next world. The famous Paleolithic burial site of Sungir in Russia, where the remains of a man, a woman, and two children were interred with thousands of mammoth ivory beads and other precious objects, attests to the importance of honoring the dead in prehistoric societies.

As prehistoric cultures developed more complex forms of social organization, ancestor worship practices became increasingly elaborate and institutionalized. The construction of burial mounds and megalithic tombs, such as the Neolithic passage graves of Western Europe and the Native American mound-building cultures of the Mississippi Valley, demonstrates the significant investment of time, labor, and resources that ancient societies dedicated to honoring their ancestors. These monumental structures not only served as repositories for the remains of the dead but also as powerful symbols of the enduring connections between the living and the ancestral spirits.

The veneration of ancestors in prehistoric societies may have served several important social and psychological functions. By honoring the spirits of the dead, the living could maintain a sense of continuity with the past and reinforce their sense of identity and belonging within a larger lineage or clan. The construction of impressive burial mounds and megalithic tombs may have also served to legitimize the power and authority of ruling elites, who claimed descent from illustrious ancestors and used ancestor worship practices to bolster their social and political status.

Moreover, ancestor worship may have been seen as a means of ensuring the well-being and prosperity of the living community. By propitiating the spirits of the dead through offerings, rituals, and the maintenance of their burial sites, prehistoric societies sought to secure the blessings and protection of their ancestors. This belief in the ongoing influence of the dead on the living world is evidenced by the widespread practice of secondary burial, in which the bones of the deceased were carefully curated and often incorporated into communal ossuaries or shrines.

The significance of ancestor worship in prehistoric societies is further underscored by the frequent depiction of ancestral figures in ancient art and iconography. From the stylized “ancestor stones” of the Konso people of Ethiopia to the intricate sarcophagi of the Chachapoyas culture in Peru, the representation of the dead in material culture attests to the central role of ancestor veneration in prehistoric religious beliefs and practices.

The Relationship Between Prehistoric Religion and the Cosmos

In prehistoric times, the celestial realm was not merely seen as a distant and unreachable expanse but as a powerful and sacred presence that profoundly influenced the lives of human beings. The sun, moon, stars, and constellations were imbued with deep spiritual significance, and their movements and cycles were carefully observed and incorporated into the religious beliefs and practices of ancient societies around the world.

One of the most striking examples of the relationship between prehistoric religion and the cosmos can be found in the ancient megalithic monuments of Europe, such as Stonehenge in England and Newgrange in Ireland. These impressive structures, which date back to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, are aligned with the movements of the sun and the moon, suggesting that they served as astronomical observatories and sacred sites for the veneration of celestial deities. The precise alignment of these monuments with the summer and winter solstices, as well as the spring and autumn equinoxes, attests to the sophisticated understanding of celestial cycles and their importance in prehistoric spiritual practices.

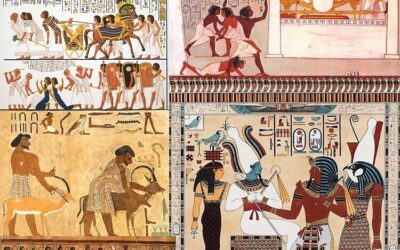

Similarly, the ancient Egyptians developed a complex system of celestial religion that revolved around the worship of the sun god Ra and the star Sirius, which was associated with the goddess Isis. The annual flooding of the Nile, which was essential for the survival and prosperity of Egyptian civilization, was linked to the heliacal rising of Sirius, and the Egyptians developed a sophisticated calendar system based on the movements of this star. The construction of the Great Pyramids of Giza, which are precisely aligned with the cardinal directions and the position of the stars in the constellation of Orion, further underscores the deep connection between Egyptian religion and the cosmos.

In the Americas, the ancient Maya and Aztec civilizations also developed elaborate systems of celestial religion and astronomy. The Mayan calendar, which was based on the cycles of the sun, moon, and planets, was intimately connected with Mayan spiritual beliefs and practices, and the construction of impressive ceremonial centers such as Chichen Itza and Tikal was guided by precise astronomical alignments. The Aztecs, similarly, built their capital city of Tenochtitlan in accordance with a cosmic plan, with the Templo Mayor serving as a symbolic representation of the celestial realm and the birthplace of the sun.

The celestial realm also played a crucial role in the spiritual beliefs and practices of prehistoric societies in Asia and the Pacific. The ancient Chinese developed a sophisticated system of astrology and divination based on the movements of the stars and planets, and the construction of the Great Wall of China is said to have been guided by the position of the stars in the night sky. In Polynesia, the navigational skills of the ancient seafarers were closely linked to their spiritual beliefs, with the stars and constellations serving as sacred guides and protectors on their long voyages across the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

As prehistoric societies developed more complex forms of social organization and religious belief, the relationship between religion and the cosmos took on new dimensions. The development of early astronomical knowledge and calendar systems, which were essential for the timing of agricultural activities and the coordination of religious festivals, was closely intertwined with the evolution of spiritual beliefs and practices. The construction of large-scale ceremonial centers and the emergence of priestly classes, who were responsible for the observation and interpretation of celestial phenomena, further institutionalized the connection between religion and the cosmos.

In conclusion, the relationship between prehistoric religion and the cosmos was a profound and multifaceted one, influencing the development of early astronomical knowledge, calendar systems, and architectural design. The celestial realm was imbued with deep spiritual significance, and the movements and cycles of the sun, moon, stars, and planets were carefully observed and incorporated into the religious beliefs and practices of ancient societies around the world. As we continue to explore the rich spiritual heritage of our prehistoric ancestors, the enduring power of the cosmos as a source of wonder, inspiration, and meaning reminds us of the timeless human quest to understand our place in the vast and mysterious universe.

The Influence of Prehistoric Religion on the Emergence of Social Complexity

Religion has played a crucial role in the development of social complexity throughout human history, and this is particularly evident in the study of prehistoric societies. As ancient cultures transitioned from small, egalitarian hunter-gatherer bands to larger, more stratified agricultural communities, religious beliefs and practices served to legitimize emerging social hierarchies, facilitate the mobilization of labor, and foster a sense of shared identity among diverse populations.

One of the key ways in which religion influenced the emergence of social complexity was through the development of specialized religious roles and institutions. The rise of shamans, priests, and other religious specialists in prehistoric societies marked a significant shift in the organization of spiritual authority, with these individuals often wielding considerable social and political power. The construction of large-scale ceremonial centers, such as the ancient city of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, which predates the advent of agriculture by several thousand years, suggests that religious institutions played a central role in the mobilization of labor and resources in prehistoric societies.

As prehistoric societies grew in size and complexity, religion also served to legitimize the authority of emerging political leaders and social elites. The construction of impressive burial mounds and megalithic tombs, such as the Egyptian pyramids and the Mayan temples of Central America, was often associated with the veneration of powerful rulers and their ancestral lineages. By claiming divine sanction for their rule and demonstrating their ability to harness the power of the gods through elaborate religious ceremonies and monumental architecture, these leaders were able to consolidate their political power and maintain social order.

Religion also played a crucial role in the development of social stratification and the emergence of distinct social classes in prehistoric societies. The creation of elaborate burial practices and the inclusion of precious grave goods in the tombs of social elites, such as the famous Tomb of the Astronaut in Paracas, Peru, suggests that religious beliefs about the afterlife were used to reinforce social hierarchies and maintain the privileged status of ruling elites. The development of specialized craft production, such as the manufacture of religious artifacts and ceremonial objects, also contributed to the emergence of social stratification, with skilled artisans and craftspeople often enjoying higher social status and economic rewards.

Another important way in which religion influenced the emergence of social complexity was through the development of shared cultural identities and the promotion of social cohesion. The construction of large-scale ceremonial centers and the participation in communal religious rituals, such as the Neolithic henge monuments of Britain and Ireland, served to bring together diverse communities and foster a sense of shared purpose and identity. The development of common mythologies and religious beliefs, such as the widespread veneration of mother goddesses in prehistoric Europe and the Middle East, also contributed to the creation of shared cultural norms and values that helped to unite disparate populations.

As prehistoric societies developed into early states and empires, religion continued to play a central role in the legitimization of political authority and the maintenance of social order. The deification of powerful rulers, such as the Egyptian pharaohs and the Inca emperors of South America, served to reinforce the divine

Clues to Religion in Evolutionary Analogues:

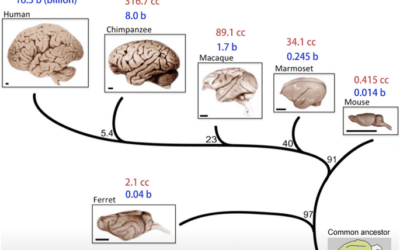

The Religious and Meaning-Making Functions of the Human Brain and Whale Social Behavior

Recent studies in neuroscience and comparative psychology have shed light on the remarkable similarities between the social and cognitive capacities of humans and whales, particularly in relation to the religious and meaning-making functions of the brain. These findings suggest that the evolutionary development of these functions may be rooted in the social and emotional needs of highly intelligent, social species.

The Neurological Basis of Religious Experience:

In humans, the religious and meaning-making functions of the brain are associated with a complex network of neural structures, including the prefrontal cortex, the limbic system, and the temporal lobes. These regions are involved in various aspects of religious experience, such as the formation of beliefs, the experience of emotions, and the attribution of meaning to events and symbols.

One key structure in this network is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which plays a role in the experience of empathy, social bonding, and the processing of emotional and spiritual experiences. The ACC is also involved in the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, which may explain the intense physiological responses (e.g., chills, tears) that often accompany religious experiences.

Whale Social Behavior and Emotional Processing:

Whales, particularly highly social species like killer whales and sperm whales, have been observed engaging in complex social behaviors that suggest a capacity for empathy, cooperation, and emotional processing similar to that of humans. For example, killer whales have been known to exhibit signs of grief and mourning when a member of their pod dies, and sperm whales have been observed engaging in cooperative hunting and problem-solving behaviors.

Recent studies have also shown that whales possess a highly developed paralimbic system, which includes structures like the anterior cingulate cortex and the insular cortex. These regions are involved in the processing of emotions and the experience of social bonding, suggesting that whales may have a neurological capacity for religious and meaning-making experiences similar to that of humans.

The Religious and Meaning-Making Functions of the Human Brain and Ape/Hominid Social Behavior

Recent studies in neuroscience and comparative psychology have revealed intriguing similarities between the social and cognitive capacities of humans and our closest living relatives, the great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans), as well as extinct hominid species. These findings suggest that the evolutionary development of religious and meaning-making functions in the human brain may be rooted in the social and emotional needs of highly intelligent, social primates.

The Neurological Basis of Religious Experience in Humans:

In humans, the religious and meaning-making functions of the brain are associated with a complex network of neural structures, including the prefrontal cortex, the limbic system, and the temporal lobes. These regions are involved in various aspects of religious experience, such as the formation of beliefs, the experience of emotions, and the attribution of meaning to events and symbols.

One key structure in this network is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which plays a role in the experience of empathy, social bonding, and the processing of emotional and spiritual experiences. The ACC is also involved in the regulation of the autonomic nervous system, which may explain the intense physiological responses (e.g., chills, tears) that often accompany religious experiences.

Ape and Hominid Social Behavior and Emotional Processing:

Great apes, particularly chimpanzees and bonobos, exhibit complex social behaviors that suggest a capacity for empathy, cooperation, and emotional processing similar to that of humans. For example, chimpanzees have been observed engaging in altruistic behaviors, such as sharing food with unrelated individuals, and displaying signs of emotional contagion, such as responding to the distress of others with consolation and comfort.

Studies of extinct hominid species, such as Neanderthals and Homo erectus, have also revealed evidence of social bonding and emotional processing. For instance, Neanderthal burial practices, which often included the use of grave goods and the careful positioning of the body, suggest a capacity for symbolic thought and a possible belief in an afterlife. Similarly, the presence of symbolic artifacts, such as engraved shells and pigments, in Homo erectus sites indicates a capacity for abstract thought and the attribution of meaning to objects and events.

Neurological Similarities Between Humans and Apes:

Comparative neurological studies have shown that the brains of great apes, particularly chimpanzees and bonobos, share many structural and functional similarities with the human brain. For example, like humans, great apes possess a well-developed prefrontal cortex, which is involved in higher-order cognitive functions such as planning, decision-making, and social cognition. They also have a large and complex limbic system, which is involved in the processing of emotions and the regulation of social behavior.

Recent studies have also shown that great apes possess von Economo neurons, which are specialized cells found in the anterior cingulate cortex and the fronto-insular cortex of humans and are thought to play a role in social cognition and empathy. The presence of these neurons in great apes suggests that they may have a neurological capacity for social bonding and emotional processing similar to that of humans.

Clues in Prehistory for Developing Religion:

The Role of Symbolic Thinking:

The use of symbolism is a universal feature of religious behavior, and evidence of symbolic thinking in the archaeological record is often interpreted as a sign of cognitive complexity and the capacity for religious thought. Some of the earliest evidence of symbolic behavior comes from Middle Stone Age sites in Africa, where pigments such as red ochre were used for potentially ritualistic purposes as early as 100,000 years ago. The creation of representational art, such as the half-human, half-animal figures depicted in Upper Paleolithic cave paintings, further demonstrates the ability to communicate abstract concepts and to imagine supernatural beings.

Paleolithic Burials and the Afterlife:

The ritual treatment of the dead is often considered one of the earliest and most reliable indicators of religious thought in the archaeological record. Paleolithic burials, which date back to at least 100,000 years ago, suggest an awareness of mortality and possibly a belief in an afterlife. The inclusion of grave goods, such as tools, ornaments, and animal remains, in these burials may reflect an emotional connection with the deceased and a belief that these items would be needed in the next life. The use of red ochre in some Paleolithic burials, as seen at the Qafzeh Cave in Israel, may have served a symbolic or ritualistic purpose related to the concept of life and death.

The Emergence of Shamanism:

Some researchers have proposed that shamanism, a practice involving altered states of consciousness and communication with supernatural entities, may have been one of the earliest forms of religious behavior. Evidence for shamanic practices in the Upper Paleolithic comes from the depiction of therianthropic (part-human, part-animal) figures in cave art, which may represent shamans in a trance state or spirit beings. The use of psychoactive substances and the presence of elaborate burial practices in some Upper Paleolithic cultures further support the idea that shamanism may have played a significant role in early religious traditions.

The Neolithic Revolution and the Rise of Organized Religion:

The Neolithic Revolution, which began around 11,000 years ago, marked a major transition in human societies from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to one based on agriculture and permanent settlements. This shift had profound implications for the development of religious beliefs and practices, as the new social and economic conditions necessitated more complex forms of social organization and the justification of centralized authority. The emergence of organized religion in the Neolithic period served to provide social and economic stability, to legitimize political power, and to foster cooperation among large groups of unrelated individuals.

The Invention of Writing and the Codification of Religious Beliefs:

The invention of writing, which occurred independently in several parts of the world around 5,000 years ago, played a crucial role in the development and spread of organized religion. By allowing for the recording and transmission of religious texts, writing enabled the codification of religious beliefs and practices, making them less dependent on oral traditions and individual memory. The oldest known religious texts, such as the Pyramid Texts from ancient Egypt (dating to around 2400-2300 BCE), demonstrate the importance of writing in the establishment and maintenance of formal religious systems.

The Role of Art and Symbolism in Prehistoric Religion:

Art and symbolism played a crucial role in the religious practices of prehistoric humans, serving as a means of communicating complex ideas, evoking powerful emotions, and connecting with the spiritual world. One of the most striking examples of this is the use of red ochre, a naturally occurring pigment that has been found in numerous prehistoric sites around the world.

Red ochre has been used by humans for at least 300,000 years, and its symbolic significance appears to have been widespread. In many prehistoric cultures, red ochre was associated with blood, life, and fertility, and was often used in burial rituals and other religious ceremonies. The use of red ochre in prehistoric art, such as the famous “Red Lady of Paviland” in Wales, suggests that it may have been seen as a way of imbuing the artwork with spiritual power and significance.

Another example of the role of art and symbolism in prehistoric religion is the creation of symmetrical axeheads and other artifacts that appear to have had no practical purpose. These objects, which have been found in many prehistoric sites, are often made from exotic materials and are carefully crafted to achieve a high degree of symmetry and balance.

Researchers have suggested that these artifacts may have been used in religious rituals or as sacred objects, serving as a means of connecting with the spiritual world and evoking a sense of awe and mystery. The fact that these objects were often made from materials that were difficult to obtain and had no practical use suggests that they were imbued with a deep symbolic significance that went beyond their functional value.

The Significance of Animism in Prehistoric Religion:

Animism, or the belief that all things, including animals, plants, and even inanimate objects, possess a spiritual essence or soul, is thought to have been a common feature of prehistoric religions around the world. This belief system may have emerged as a way of making sense of the complex and often unpredictable nature of the world, and of establishing a sense of connection and kinship with the natural environment.

In many prehistoric cultures, animals were seen as powerful spiritual beings that could influence human lives in both positive and negative ways. The depiction of animals in prehistoric art, such as the famous cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira, suggests that they were often revered as sacred beings and were associated with a range of symbolic meanings and mythological stories.

Similarly, the veneration of natural features such as mountains, rivers, and trees was a common feature of prehistoric animistic beliefs. These features were often seen as sacred sites where the boundaries between the human and spiritual worlds were particularly thin, and where communication with the spirits was possible through ritual and sacrifice.

The Blurring of Boundaries Between the Physical and Spiritual Worlds:

Another key feature of prehistoric religion appears to have been the blurring of boundaries between the physical and spiritual worlds. This is evident in the way that prehistoric art often depicts human and animal forms merging and transforming into one another, as well as in the use of hallucinogenic substances and other techniques for inducing altered states of consciousness.

One theory is that prehistoric humans may have seen the spiritual world as a realm that existed alongside and interpenetrated the physical world, rather than as a separate and distinct domain. This worldview may have been reinforced by the use of psychoactive plants and other substances, which could induce powerful visions and experiences of transcendence and connection with the divine.

The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of New Religious Forms:

The Neolithic Revolution, which began around 12,000 years ago and saw the emergence of agriculture and settled communities, also had a profound impact on prehistoric religion. As human societies became more complex and stratified, new forms of religious practice and belief began to emerge, often centered around the veneration of ancestors, the worship of gods and goddesses associated with fertility and agriculture, and the construction of large-scale monuments and temples.

One of the most striking examples of this is the Göbekli Tepe site in Turkey, which dates back to around 9000 BCE and is considered one of the oldest known examples of monumental architecture in the world. The site consists of a series of circular enclosures, each surrounded by massive stone pillars carved with intricate depictions of animals and human-like figures.

Researchers believe that Göbekli Tepe may have been a sacred site where people from different communities gathered to perform religious rituals and ceremonies, and that it may have played a key role in the emergence of new forms of religious belief and practice during the Neolithic period.

Timeline of Non Human Religious Development:

Timeline of Prehistoric Religious Development:

Lower Paleolithic (2.5 million to 300,000 years ago):

Homo habilis and early Homo erectus emerge, with larger brains and increased cognitive capabilities compared to earlier hominids.

Potential development of theory of mind and ability to attribute agency to external forces, setting the stage for animistic beliefs.

Middle Paleolithic (300,000 to 50,000 years ago):

Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens engage in ritual behavior, such as intentional burials with grave goods (e.g., Shanidar Cave in Iraq, La Ferrassie in France).

Possible use of ochre for symbolic purposes, suggesting early forms of ritual and belief.

Increased brain size and complexity, particularly in regions associated with language and abstract thinking, may have facilitated the development of symbolic thought and religious concepts.

Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 12,000 years ago):

Explosion of symbolic expression, including cave paintings (e.g., Chauvet Cave in France, Lascaux Cave in France), figurines (e.g., Venus of Willendorf in Austria), and other non-functional art objects.

Elaboration of burial practices, such as the use of red ochre and inclusion of ornaments and tools with the deceased (e.g., Sungir site in Russia).

Possible evidence of shamanism and ritual specialists, as suggested by the “Lion Man” figurine from Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave in Germany.

Development of complex language and storytelling, which could have facilitated the transmission of religious beliefs and mythologies.

Mesolithic (12,000 to 8,000 years ago):

Emergence of sedentary communities and early agriculture, leading to changes in social structure and the potential for more organized religious practices.

Evidence of large-scale ritual structures, such as Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, which may have served as early temples or gathering places for religious ceremonies.

Neolithic (8,000 to 3,000 years ago):

Rise of agriculture and settled societies, leading to the development of more complex religious systems and the emergence of priestly classes.

Appearance of megalithic structures, such as Stonehenge in England, which likely served religious or astronomical purposes.

Early evidence of ancestor worship and the veneration of deities associated with natural forces and fertility (e.g., the Mother Goddess figurines from Çatalhöyük in Turkey).

Ancient North Asian Civilization:

The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture in Siberia (24,000 to 15,000 years ago) provides evidence of early ritualistic behavior, including the use of ornaments, figurines, and the burial of individuals with grave goods.

The presence of Venus figurines and other symbolic objects in this region suggests the development of religious beliefs and practices, possibly related to fertility and the veneration of female deities.

This timeline presents a hypothetical progression of religious development in prehistoric humans, based on available archaeological evidence and current anthropological theories. The inclusion of significant neurological changes in Homo sapiens relative to earlier hominids provides a plausible explanation for the emergence of symbolic thought and religious behavior. However, much is still speculative considering the limited evidence from these periods; the interpretation of artifacts as religious or ritualistic remains a subject of ongoing debate among scholars.

Clues to Early Religion in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture

The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, which existed in Siberia between 24,000 and 15,000 years ago, has been studied by archaeologists and anthropologists for its potential role in shaping the development of early religious beliefs and practices. While it is challenging to draw direct connections between this ancient culture and the major world religions that emerged much later, some scholars argue that the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture may have provided a template or foundation for the evolution of religious thought as human populations migrated across the globe.

Archaeological evidence from the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture suggests the presence of ritualistic behavior, as indicated by the discovery of ornaments, figurines, and burial practices. These findings hint at the existence of a belief system that recognized the importance of symbolism, the afterlife, and possibly the veneration of deities or spirits.

As human populations migrated from Siberia to other parts of the world, they likely carried with them the basic elements of this early belief system. Over time, these beliefs and practices evolved and adapted to new environments, social structures, and cultural influences, giving rise to the diverse array of religious traditions we see today.

One theory proposes that the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture may have influenced the development of shamanism, a practice found in many ancient and modern cultures across the world. Shamanism involves the belief in a spiritual realm and the ability of certain individuals (shamans) to communicate with spirits and deities through altered states of consciousness. The presence of figurines and other symbolic objects in Mal’ta-Buret’ sites could be interpreted as evidence of early shamanic practices.

As populations migrated from Siberia to other regions, shamanic beliefs and practices may have spread and evolved, adapting to new cultural contexts. For example, in Central Asia, shamanism blended with local beliefs and eventually gave rise to practices such as ancestor worship and animism. In Europe, shamanic traditions may have influenced the development of pagan religions, such as the Norse and Celtic belief systems.

Another theory suggests that the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture may have played a role in the development of goddess worship and fertility cults. The discovery of female figurines, some with exaggerated sexual characteristics, has led some researchers to propose that the Mal’ta-Buret’ people recognized the importance of fertility and the feminine divine. As populations migrated, these beliefs may have evolved into the various mother goddess cults found in ancient Mediterranean, Near Eastern, and European cultures.

The migrations of people from Siberia to other parts of the world also likely facilitated the exchange of ideas and the cross-pollination of religious beliefs. For example, the spread of populations from Siberia to the Americas via the Bering Land Bridge may have brought elements of Mal’ta-Buret’ beliefs into contact with the developing religious traditions of indigenous American cultures. Similarly, migrations from Siberia into East Asia may have influenced the early development of religious thought in China, Japan, and Southeast Asia.

Similarities in Early Mythological Systems to the Malta Buret Culture:

The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, which thrived in Siberia between 24,000 and 15,000 years ago, has captured the attention of archaeologists and anthropologists due to its potential influence on the development of religious beliefs and mythological themes across the globe. As human populations migrated from this region, they likely carried with them the basic elements of the Mal’ta-Buret’ belief system, which later evolved and adapted to new cultural contexts. Remarkably, certain archetypes and motifs found in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture appear to have parallels in the mythologies of various civilizations, suggesting a common ancestral source for these ideas.

One of the most prominent archetypes that can be traced back to the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture is the trickster figure. Trickster gods and spirits are found in numerous mythologies worldwide, often characterized by their cunning, mischief, and ability to challenge the established order. In many cases, these trickster figures are associated with the creation of the world or the origins of human culture. For example:

In Norse mythology, Loki is a shape-shifting trickster god who plays a central role in many mythical stories, including the creation of Thor’s hammer and the death of Baldr. Loki’s ambiguous nature and ability to both help and hinder the other gods reflect the complex role of trickster figures in mythology.

In many Native American mythologies, the coyote is portrayed as a trickster spirit, often responsible for creating the world or stealing fire for humanity. The coyote’s clever and mischievous nature mirrors that of other trickster figures, such as the raven in Inuit mythology or the spider in West African folklore.

In ancient Greek mythology, Prometheus, a Titan who stole fire from the gods and gave it to humanity, embodies the trickster archetype. His defiance of the gods and his role in the creation of human culture echo the themes associated with trickster figures in other mythologies.

The presence of trickster figures in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture is suggested by the discovery of anthropomorphic figurines and the depiction of hybrid human-animal forms in their artwork. These representations may have served as early precursors to the trickster archetypes found in later mythologies, reflecting the Mal’ta-Buret’ people’s belief in the transformative power of supernatural beings.

Another significant motif that appears to have originated in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture is the creation of humans from clay. This theme is found in numerous creation myths across the world, often involving a divine figure or trickster god molding humans from clay or earth. For instance:

In the Babylonian creation myth, Enuma Elish, the god Marduk creates humans from the blood of the slain god Kingu, mixed with clay.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the Book of Genesis describes how God formed Adam, the first man, from the dust of the ground and breathed life into him.

In many Native American creation stories, such as those of the Hopi and the Zuni, humans are molded from clay by the Creator or other divine beings.

The origins of this clay-creation motif may lie in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture’s use of clay figurines, which were likely imbued with spiritual or ritualistic significance. As the concept spread with human migrations, it evolved into the various creation myths we see today, each reflecting the unique cultural context in which it developed.

The Mal’ta-Buret’ culture may have also influenced the widespread appearance of serpent and turtle symbolism in world mythologies. Serpents and turtles are often associated with creation, fertility, and the cycle of life and death. In many cultures, these animals are seen as intermediaries between the earthly and divine realms, or as embodiments of primordial forces. For example:

In Hindu mythology, the serpent Shesha is portrayed as the cosmic snake upon which Lord Vishnu rests between cycles of creation, while the turtle Kurma serves as the foundation for the churning of the cosmic ocean.

In ancient Egyptian mythology, the serpent Apep represents the forces of chaos and darkness, while the turtle is associated with the god Ptah, who is credited with creating the world through the power of his speech.

In Mesoamerican mythologies, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl is a central figure, often associated with creation, fertility, and the cycle of life and death. Similarly, the concept of the World Turtle, upon whose back the earth rests, is found in various Native American creation stories.

The presence of serpent and turtle imagery in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture, as evidenced by the discovery of carved figurines and decorative motifs, suggests that these symbols held significant spiritual meaning for the ancient Siberians. As these ideas spread with human migrations, they likely influenced the development of serpent and turtle symbolism in other cultures, adapting to local beliefs and traditions.

Another universal motif that may have its roots in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture is the concept of the World Tree. The World Tree is a cosmic symbol representing the connection between the earthly realm and the divine, often depicted as a gigantic tree that spans the three levels of the universe: the underworld, the earth, and the heavens. This motif is found in numerous mythologies, such as:

In Norse mythology, the World Tree is Yggdrasil, a giant ash tree that connects the Nine Worlds and is tended by the Norns, who determine the fate of all beings.

In many Native American mythologies, the World Tree is a central feature of the cosmos, often represented by a cedar, pine, or cottonwood tree. The tree is seen as a pathway between the earthly and spiritual realms, and is often associated with the four cardinal directions.

In Siberian shamanic traditions, the World Tree is a common symbol, representing the axis mundi, or the center of the world. Shamans are believed to climb the World Tree during their spiritual journeys, accessing the different levels of the universe.

The origins of the World Tree concept may be traced back to the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture’s reverence for trees and their use of wooden poles in ritualistic contexts. As this idea spread with human migrations, it evolved into the various World Tree myths we see in later cultures, each reflecting the unique spiritual and ecological landscape in which it developed.

Finally, the theme of birth from water or primordial oceans is another universal motif that may have been influenced by the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture. In many creation myths, the world emerges from a vast, primordial ocean, often through the actions of a divine being or creature. This theme is found in various mythologies, such as:

In the Norse creation myth, the world is formed from the body of the primordial giant Ymir, who emerges from the void between the realms of fire and ice. The oceans are created from his blood, and the earth from his flesh.

In the Iroquois creation story, the world is created when Sky Woman falls from the heavens onto the back of a great turtle swimming in the primordial ocean. The turtle’s back becomes the earth, and life springs forth from it.

In the ancient Egyptian creation myth, the god Atum emerges from the primordial waters of Nun, creating the world and the other gods through his own power.

The concept of birth from water may have its origins in the Mal’ta-Buret’ culture’s proximity to Lake Baikal, the largest freshwater lake in the world, and the Angara River. The spiritual significance of these bodies of water, as evidenced by the discovery of ritualistic objects and burials near the shorelines, may have influenced the development of primordial ocean myths as the Mal’ta-Buret’ people migrated to other regions.

Migration Patterns and Interactions with Other Cultures: