Dedication :

The late author of Freud: The Making of an Illusion, Dr. Fredrick Crews was a pen pal of mine. He was an eternally interesting and a sardonic rapier sharp wit, with a shrewd eye for empirical hygiene but also a clear head and fascinating perspective up to the end of his life. His death in June ’24 marks the end of our correspondence but not the influence of his work. I would highly recommend his book on Freud, as it is based on the most recent archive disclosures available and one of the best researched that is out there. One can feel his keen and discerning mind digging through archives the whole way through. “Show me the Evidence!” Dr. Crews would often say to me, and psychologists should continue to be beholden to his maxim to build a future for psychology with scientific evidence, integrity, and intellectual honesty.

Freud

“Freud: The Making of an Illusion” by Frederick Crews, a critical reexamination of Freud’s life and legacy.

In his meticulously researched and fiercely argued book “Freud: The Making of an Illusion,” Frederick Crews presents a scathing critique of Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. Crews argues that Freud’s towering reputation is built on a foundation of pseudoscience, deception, and self-delusion. Through a close examination of Freud’s life and works, Crews seeks to debunk the myth of the heroic discoverer of the unconscious and expose the man behind the legend – a brilliant but deeply flawed individual whose theories tell us more about his own psyche than the human condition.

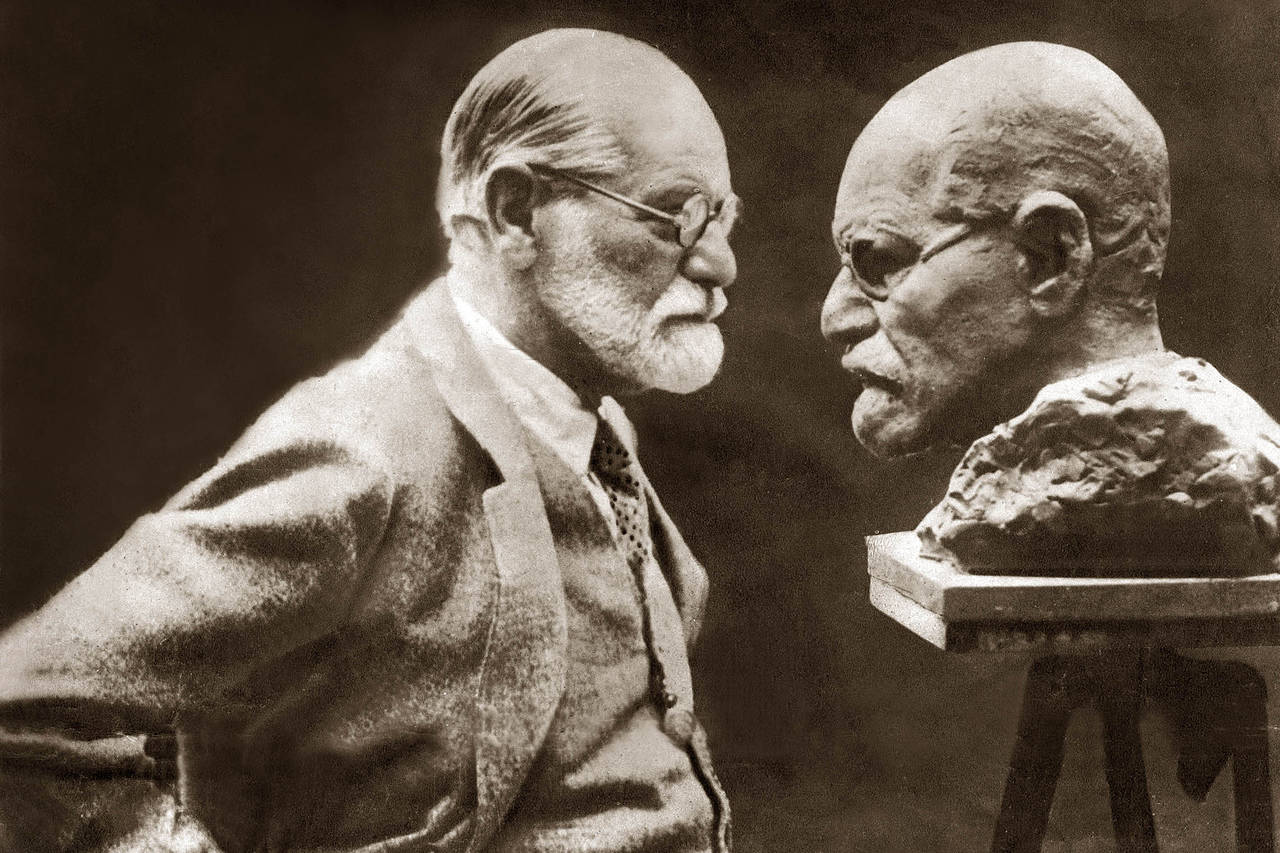

The Enigma of Freud

Sigmund Freud is one of the most influential and controversial figures of the 20th century. His ideas about the unconscious, sexuality, and the psychodynamics of the mind have permeated Western culture, shaping the way we think about ourselves and others. Yet despite his enduring fame, Freud remains an enigmatic and polarizing figure. To his admirers, he was a visionary thinker who boldly explored the hidden depths of the psyche, a latter-day Copernicus of the mind. To his critics, he was a pseudoscientific charlatan who built an empire on unproven speculations and foisted his own neuroses onto humanity.

Crews situates himself firmly in the latter camp. Drawing on a wealth of historical evidence and scholarly research, he presents a devastating indictment of Freud’s character and intellectual integrity. He portrays Freud as a man driven by ambition, seduced by his own rhetoric, and willing to distort facts to fit his preconceived theories. In Crews’ telling, psychoanalysis was not a science but a cult, with Freud as its charismatic and authoritarian leader.

The Seeds of Psychoanalysis

To understand the making of the Freudian illusion, Crews argues, we must begin with Freud’s early life and the cultural milieu of fin-de-siècle Vienna. Born into a Jewish family in 1856, Freud grew up in an era of rapid social change and intellectual ferment. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was in decline, traditional values were under siege, and new ideas in science, philosophy, and the arts were challenging old certainties.

As a young medical student, Freud was drawn to the study of the nervous system and the riddles of the mind. But he was also ambitious, eager for fame and fortune. When his research on cocaine as a wonder drug ended in failure and scandal, he turned to the fledgling field of psychotherapy as a promising avenue for advancement.

It was in this context, Crews contends, that Freud began to develop the ideas that would become the foundation of psychoanalysis. Drawing on his experiences with hypnosis and his treatment of “hysterical” patients, Freud formulated his theories of repression, the unconscious, and infantile sexuality. But from the start, Crews argues, these concepts were shaped more by Freud’s own preconceptions and psychological needs than by empirical evidence.

The Search for a Father Figure

From an early age, Crews argues, Freud was haunted by feelings of inadequacy and a yearning for paternal approval. His relationship with his own father, Jakob Freud, was strained and ambivalent. Jakob was a wool merchant who had been married twice before and was significantly older than Freud’s mother, Amalia. Freud resented his father’s meek acceptance of antisemitic slights and saw him as a weak and ineffectual figure.

This early experience, Crews suggests, instilled in Freud a lifelong search for powerful mentor figures who could provide the guidance and validation he craved. In his university years, Freud attached himself to a series of older, accomplished men – most notably the physiologist Ernst Brücke, who became his scientific role model and “father in the spirit.”

But Freud’s tendency to idealize his mentors was matched by an equally strong impulse to rebel against and ultimately reject them. This pattern, Crews argues, would repeat itself throughout Freud’s life and career, shaping his relationships with figures like Josef Breuer, Wilhelm Fliess, and even Carl Jung.

The Fliess Debacle and the Origins of Psychoanalysis

Freud’s relationship with Wilhelm Fliess, an ear, nose, and throat specialist he met in 1887, was particularly intense and fateful. Fliess became Freud’s confidant, collaborator, and intellectual sounding board during the crucial period when he was developing the foundations of psychoanalytic theory.

But Fliess was also, in Crews’ telling, a quack and a charlatan who developed bizarre theories about the nose as the seat of sexuality and the existence of a male menstrual cycle. Freud not only endorsed these pseudoscientific notions but subjected his own patients, most notoriously Emma Eckstein, to dangerous and disfiguring nasal surgeries at Fliess’s hands.

The Eckstein case, which left the young woman permanently scarred and nearly killed her through surgical malpractice, was a turning point in Freud’s journey. Faced with the disastrous consequences of his loyalty to Fliess, Freud engaged in a series of self-serving distortions and evasions. He minimized Fliess’s culpability, blamed Eckstein’s symptoms on hysteria, and ultimately broke with his erstwhile mentor in a bitter personal feud.

For Crews, the Fliess debacle laid bare the mechanisms of denial, projection, and rationalization that would become the hallmarks of Freudian theory. Psychoanalysis, in this view, was not a disinterested scientific enterprise but a kind of self-exculpatory myth-making, a way for Freud to transmute his own mistakes and misdeeds into universal truths about the human psyche.

The Cocaine Episode and the Lure of Fame

Freud’s early scientific career was marked by another episode that Crews sees as revealing of his character and methods. In 1884, Freud published a paper extolling the virtues of cocaine, which he had begun using himself and prescribing to patients as a panacea for various ailments.

Initially, Freud was eager to claim cocaine as his great discovery, the breakthrough that would bring him scientific fame and fortune. But when reports began to emerge of the drug’s addictive and harmful effects, Freud quickly backpedaled, minimizing his own role in promoting it and even claiming to have been unaware of its anesthetic properties.

For Crews, the cocaine episode exemplifies Freud’s lifelong pattern of overreaching, self-promotion, and subsequent retreat in the face of criticism. It also underscores his willingness to experiment on himself and others in pursuit of his theories, a tendency that would resurface in his later use of pressure techniques and suggestion to elicit “memories” of childhood seduction.

The Minna Bernays Affair and the Oedipus Complex

Perhaps the most explosive of Crews’ revelations concerns Freud’s relationship with his sister-in-law, Minna Bernays. Drawing on hotel records and other archival evidence, Crews makes a persuasive case that Freud and Bernays had an affair that lasted for years and was known to his inner circle.

The significance of this liaison, for Crews, goes beyond mere biographical titillation. He argues that Freud’s guilt over the affair, and his efforts to conceal it, played a crucial role in the development of his signature concept, the Oedipus complex.

Freud’s original seduction theory posited that neuroses were caused by actual childhood sexual abuse. But in 1897, he abruptly abandoned this idea, claiming that his patients’ memories of seduction were in fact fantasies, wishful projections of their own incestuous desires. This reversal, which Freud himself dubbed his “great secret,” has long been a source of controversy and speculation.

Crews argues that Freud’s about-face was motivated, at least in part, by his need to deflect attention from his own sexual transgressions. By universalizing the notion of incestuous desires and locating them in the realm of fantasy, Freud could simultaneously absolve himself of guilt and reinforce his thesis of infantile sexuality.

The Oedipus complex, in this reading, was not a scientific discovery but a self-serving projection, a way for Freud to normalize his own forbidden desires and experiences. His insistence on the centrality of the Oedipus complex to all human development, and his intolerance of dissent on this point, takes on a new light in the context of his secret affair.

The Break with Jung and the End of the Affair

Freud’s relationship with Carl Jung, his chosen heir and successor, was in many ways a recapitulation of his earlier mentorship by Fliess. Like Fliess, Jung began as an ardent disciple but eventually challenged Freud’s authority and developed his own rival theories.

Crews argues that the break between Freud and Jung, which came to a head in 1913, was not just a theoretical dispute but a deeply personal rupture. Jung had become aware of Freud’s affair with Minna Bernays and confronted him about it, leading to a series of recriminations and counter-accusations.

For Freud, Jung’s defection was a narcissistic blow, a rejection by the son and heir he had hand-picked to carry on his legacy. He responded with a campaign of character assassination, accusing Jung of harboring antisemitic attitudes and succumbing to religious mysticism.

The break with Jung, Crews suggests, marked the end of Freud’s most productive period and the beginning of his descent into dogmatism and isolation. In his later years, Freud became increasingly intolerant of dissent, expelling anyone who challenged his authority or deviated from orthodox Freudianism.

…

Conclusion

Crews’ portrait of Freud is that of a brilliant but deeply flawed man, a visionary thinker whose theories were inextricably bound up with his own psychological wounds and moral failings. By exposing the personal and historical context behind Freud’s ideas, Crews challenges the myth of psychoanalysis as a objective science and invites us to see it as a kind of secular religion, with Freud as its charismatic but fallible prophet.

This demystification of Freud is bound to be controversial, and some may accuse Crews of engaging in a kind of retroactive psychoanalysis, of subjecting Freud to the very techniques of interpretation and exposure that he pioneered. But for those willing to grapple with the complexity and contradictions of Freud’s life and work, Crews’ book offers a bracing and revelatory perspective.

The Seduction Theory Fiasco

Crews sees Freud’s brief advocacy of the “seduction theory” as a prime example of his tendency to let his speculations outrun the facts. In the mid-1890s, based on his clinical work, Freud became convinced that neuroses were caused by repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse. He claimed to have uncovered numerous cases of incest and molestation, perpetrated even by respectable middle-class fathers.

But when this shocking theory met with skepticism and resistance from his colleagues, Freud quickly backpedaled. He now claimed that the memories of abuse were not real but fantasies, wishful projections of the child’s own Oedipal desires. The seduction theory was abandoned and the Oedipus complex – the linchpin of Freudian theory – was born.

For Crews, this episode reveals the fundamental dishonesty and self-deception at the heart of Freud’s method. Freud was not a disinterested scientist following the evidence where it led, but a dogmatic theorist who twisted facts to suit his preconceived notions. The seduction theory fiasco set the pattern for the later development of psychoanalysis – a grandiose intellectual edifice built on the shifting sands of speculation and assertion.

The Tyranny of Oedipus

The Oedipus complex, for Freud, was the nuclear complex of the neuroses – the universal psychosexual drama that shaped every aspect of mental life. According to Freudian theory, every child unconsciously desires the parent of the opposite sex and wants to eliminate the same-sex rival. The resolution of this conflict through repression and identification is the key to normal development; its failure leads to neurosis and perversion.

Crews sees the Oedipus complex as Freud’s greatest and most pernicious invention – a pseudoscientific myth masquerading as a profound truth about human nature. He argues that there is no credible evidence for the universality of Oedipal desires, and that Freud’s insistence on interpreting all human behavior through this narrow lens led to a grotesque distortion of reality.

Freud’s Oedipal obsession, Crews suggests, was rooted in his own unresolved feelings towards his parents – his idealization of his mother and his ambivalence towards his father. By elevating the Oedipus complex to the status of a universal law, Freud was projecting his own family romance onto humanity. Psychoanalysis, in this sense, was a kind of autobiographical fiction, a grandiose attempt to make sense of Freud’s own psyche.

The Illusion of Therapeutic Efficacy

One of the central claims of psychoanalysis is that it is a powerful therapeutic method, capable of uncovering the hidden roots of neurosis and bringing about lasting psychological change. Freud and his followers filled countless volumes with case histories purporting to demonstrate the curative power of the talking cure.

But Crews argues that the evidence for the effectiveness of psychoanalysis is shockingly weak. He points out that Freud’s own case studies are riddled with inconsistencies, omissions, and exaggerations. Many of his most famous patients, such as Dora and the Wolf Man, show little evidence of genuine therapeutic success. Freud often claimed cures on the flimsiest of grounds, or blamed the patient’s resistance when treatment failed.

Moreover, Crews contends, the very notion of therapeutic efficacy in psychoanalysis is problematic. Since Freudian interpretations are unfalsifiable, there is no way to distinguish between genuine insight and mere suggestion. The intense emotional bond between analyst and patient, the mystique of the analytic setting, and the sheer persuasive power of Freudian rhetoric can all create an illusion of deep understanding and transformation, even in the absence of real change.

Psychoanalysis as Pseudoscience

At the heart of Crews’ critique is the argument that psychoanalysis is not a science but a pseudoscience – a belief system that mimics the trappings of scientific inquiry without adhering to its basic principles. Freud claimed that his theories were empirically grounded, based on clinical observation and rigorously tested hypotheses. But in reality, Crews argues, psychoanalysis is a closed system, immune to falsification, that simply assimilates all evidence to its pre-existing dogmas.

Freudian interpretations, Crews points out, are inherently unfalsifiable. Any challenge to psychoanalytic theory can be dismissed as resistance, any contradictory data interpreted as confirmation of the theory’s depth and subtlety. Freud’s concepts are so vague and elastic that they can be stretched to fit any set of facts. Dreams, slips of the tongue, neurotic symptoms – all become grist for the psychoanalytic mill, endlessly interpreted in light of the same Oedipal templates.

Moreover, Crews argues, Freud’s methods of data collection and theory construction were thoroughly unscientific. He relied on a small, unrepresentative sample of patients, often drawn from his own social circle. He routinely ignored or discounted evidence that didn’t fit his preconceptions. And he made sweeping generalizations about human nature based on nothing more than his own intuitions and speculations.

The Freudian Legacy

Despite these fatal flaws, Crews acknowledges, psychoanalysis has had an enormous impact on Western culture and thought. Freudian ideas have permeated literature, film, art, and popular discourse, shaping the way we think about the mind, sexuality, and human behavior. The image of Freud as a bold explorer of the psyche’s hidden depths has become a cultural archetype, a modern myth of heroic discovery.

But this very success, Crews argues, is part of the problem. The uncritical acceptance of Freudian ideas has led to a vast overestimation of their scientific validity and therapeutic value. Psychoanalysis has been granted an undeserved authority in fields far beyond its competence, from child-rearing to literary criticism to social policy. And it has spawned a host of dubious therapeutic practices and pseudoscientific offshoots, from recovered memory therapy to Lacanian obscurantism.

Crews sees the enduring influence of psychoanalysis as a cautionary tale about the seductive power of grand theories and charismatic personalities. Freud’s genius, he argues, lay not in his scientific discoveries but in his ability to weave a compelling narrative, to create a mythology of the mind that resonated with the Zeitgeist of his age. Psychoanalysis thrived not because it was true but because it told us what we wanted to believe about ourselves – that our deepest secrets held the key to our destiny, that our neuroses were full of hidden meaning, that talking could heal the soul.

The Post-Freudian Landscape

In the century since Freud unveiled his theories, the intellectual landscape has shifted dramatically. New research in neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and evidence-based therapy has challenged many of the basic assumptions of psychoanalysis. The talking cure has been supplanted by drug treatments and brief, targeted interventions. The unconscious has been reframed as a product of information processing rather than a seething cauldron of repressed desires.

Yet Freud’s ghost still haunts us, Crews suggests, in subtler and more insidious ways. The Freudian emphasis on hidden meanings, on the power of the past to shape the present, on the centrality of sexuality and aggression – these tropes still permeate our culture, even as the scientific basis for them crumbles. We still see Hamlet through an Oedipal lens, still speak of Freudian slips and defense mechanisms, still seek the roots of our discontent in childhood traumas and unresolved complexes.

For Crews, the task of a post-Freudian psychology is to disentangle the valid insights of depth psychology from the pseudoscientific baggage of psychoanalysis. It is to recognize the power of unconscious processes and early experiences without reducing all human behavior to a handful of Oedipal templates. And it is to create a truly scientific understanding of the mind, one grounded in empirical evidence rather than speculative myths.

The Legacy of Psychoanalysis

“Freud: The Making of an Illusion” is a work of passionate debunking, a sustained assault on the foundations of psychoanalytic theory and practice. Crews’ erudition and argumentative firepower are formidable, and his portrait of Freud as a brilliant but deeply flawed man is compelling. Yet the very intensity of his critique may leave some readers wondering if he has not replaced one myth with another – the heroic discoverer of the unconscious with the charlatan and pseudoscientist.

Ultimately, Crews’ book is a challenge to our complacency, a call to re-examine the assumptions and prejudices that shape our understanding of the mind. It reminds us that even the most venerated ideas and institutions are products of their time and place, subject to the distortions of ego, ambition, and self-deception. And it invites us to imagine a psychology beyond Freud, one that combines the depth and subtlety of humanistic insight with the rigor and objectivity of scientific inquiry.

In this sense, “Freud: The Making of an Illusion” is more than just a biography or a work of intellectual history. It is a book about the nature of truth and illusion, the seductions of grand theory, and the eternal human struggle to understand ourselves and our world. It is a reminder that even the greatest minds are fallible, and that the search for knowledge is an endless process of questioning, testing, and revision.

As we navigate the complexities of the 21st century, with its dizzying array of therapeutic options and neurochemical wonders, Crews’ critique of Freud remains as relevant as ever. It challenges us to be skeptical of easy answers and all-encompassing explanations, to demand evidence for the claims of experts, and to recognize the limits of our own understanding. It invites us to embrace a more humble and tentative view of the psyche, one that acknowledges the vastness and mystery of the human mind, even as it seeks to chart its contours with precision and care.

In the end, perhaps the true legacy of Freud lies not in his theories or his discoveries, but in the enduring questions he posed about the nature of the self and the sources of human suffering. For all his flaws and follies, Freud remains a towering figure in the history of ideas, a thinker who dared to peer into the abyss of the unconscious and to grapple with the deepest riddles of the soul. Even as we reject his answers, we cannot help but be haunted by his questions – the questions that animated his quest and that continue to drive our own search for meaning and healing in an uncertain world.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Freud, Sigmund. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Translated by James Strachey. 24 vols. London: Hogarth Press, 1953-1974.

—. The Interpretation of Dreams. Translated by James Strachey. New York: Basic Books, 1955.

—. The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1965.

—. Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1963.

—. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. Translated by James Strachey. New York: Basic Books, 1962.

—. Totem and Taboo. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1950.

—. On Narcissism: An Introduction. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1914.

—. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1920.

—. The Ego and the Id. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1923.

—. The Future of an Illusion. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1927.

—. Civilization and Its Discontents. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1930.

—. Moses and Monotheism. Translated by James Strachey. New York: Vintage Books, 1939.

—. An Outline of Psychoanalysis. Translated by James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1940.

Freud, Sigmund, and Wilhelm Fliess. The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887-1904. Translated and edited by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Freud, Sigmund, and Carl Jung. The Freud/Jung Letters: The Correspondence Between Sigmund Freud and C. G. Jung. Edited by William McGuire. Translated by Ralph Manheim and R. F. C. Hull. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Biographies and Historical Studies

Breger, Louis. Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision. New York: Wiley, 2000.

Crews, Frederick. Freud: The Making of an Illusion. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017.

Ellenberger, Henri F. The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books, 1970.

Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. New York: W. W. Norton, 1988.

Jones, Ernest. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. 3 vols. New York: Basic Books, 1953-1957.

Makari, George. Revolution in Mind: The Creation of Psychoanalysis. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

Malcolm, Janet. In the Freud Archives. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984.

Roazen, Paul. Freud and His Followers. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975.

—. The Historiography of Psychoanalysis. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2001.

Sulloway, Frank J. Freud, Biologist of the Mind: Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend. New York: Basic Books, 1979.

Swales, Peter J. “Freud, Minna Bernays, and the Conquest of Rome: New Light on the Origins of Psychoanalysis.” The New American Review 1 (1982): 1-23.

Philosophical and Theoretical Critiques

Borch-Jacobsen, Mikkel. The Emotional Tie: Psychoanalysis, Mimesis, and Affect. Translated by Douglas Brick et al. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992.

Cioffi, Frank. Freud and the Question of Pseudoscience. Chicago: Open Court, 1998.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane. New York: Viking Press, 1977.

Derrida, Jacques. “Freud and the Scene of Writing.” In Writing and Difference, translated by Alan Bass, 196-231. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Grünbaum, Adolf. The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Lacan, Jacques. Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006.

Marcuse, Herbert. Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955.

Popper, Karl. Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. New York: Basic Books, 1962.

Ricoeur, Paul. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation. Translated by Denis Savage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1970.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology, and Religious Belief. Edited by Cyril Barrett. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966.

Feminist and Sociocultural Critiques

Chodorow, Nancy J. The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

Dollimore, Jonathan. Sexual Dissidence: Augustine to Wilde, Freud to Foucault. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Flieger, Jerry Aline. Unspeakable Subjects: The Genealogy of the Event in Early Modern Europe. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Gilman, Sander L. Freud, Race, and Gender. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman. Translated by Gillian C. Gill. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Mitchell, Juliet. Psychoanalysis and Feminism: A Radical Reassessment of Freudian Psychoanalysis. New York: Basic Books, 1974.

Rose, Jacqueline. Sexuality in the Field of Vision. London: Verso, 1986.

Sprengnether, Madelon. The Spectral Mother: Freud, Feminism, and Psychoanalysis. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Psychoanalysis and Literature/Art/Culture

Bersani, Leo. The Freudian Body: Psychoanalysis and Art. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986.

Felman, Shoshana. Literature and Psychoanalysis: The Question of Reading: Otherwise. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Holland, Norman N. The Dynamics of Literary Response. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Kofman, Sarah. The Childhood of Art: An Interpretation of Freud’s Aesthetics. Translated by Winifred Woodhull. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

Kristeva, Julia. Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art. Edited by Leon S. Roudiez. Translated by Thomas Gora, Alice Jardine, and Leon S. Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1980.

Rudnytsky, Peter L., ed. Transitional Objects and Potential Spaces: Literary Uses of D. W. Winnicott. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Trilling, Lionel. Freud and the Crisis of Our Culture. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955.

0 Comments