Friedrich Kittler: Digital Theory

I. Who was Friedrich Kittler

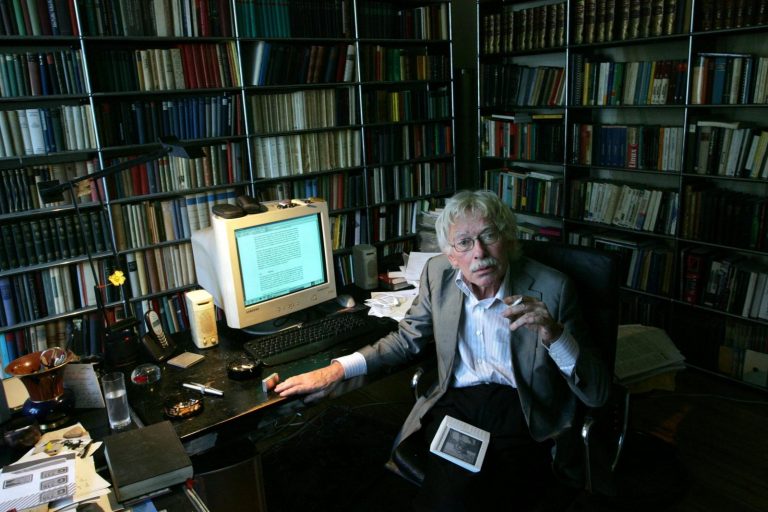

Friedrich Kittler (1943-2011) was a German literary scholar, media theorist, and cultural historian who made significant contributions to the fields of media studies, discourse analysis, and the history of technology. Kittler’s work, which draws on a wide range of disciplines including literature, philosophy, psychoanalysis, and information theory, offers a provocative and influential perspective on the ways in which media technologies shape human consciousness, culture, and society.

This paper explores the life and ideas of Friedrich Kittler, situating his thought within the historical and intellectual context of the late 20th century and examining its enduring relevance for understanding the relationship between media, technology, and the human condition. By engaging with Kittler’s key concepts, such as discourse networks, the Aufschreibesystem, and the notion of media as anthropological a priori, this paper seeks to illuminate the significance of Kittler’s work for fields such as psychology, anthropology, and media studies.

II. Biography of Friedrich Kittler

Friedrich Kittler was born in 1943 in Rochlitz, Germany, during the height of World War II. After completing his secondary education, Kittler studied German literature, Romance philology, and philosophy at the University of Freiburg, where he was influenced by the work of Martin Heidegger and Jacques Lacan. He received his doctorate in 1976 with a dissertation on the poet Conrad Ferdinand Meyer.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Kittler began to develop his distinctive approach to media theory, drawing on insights from information theory, cybernetics, and psychoanalysis. His first major work, “Discourse Networks 1800/1900,” published in 1985, established Kittler as a leading figure in the emerging field of German media studies.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Kittler held teaching positions at various universities in Germany, including the University of Bochum, the University of Kassel, and the Humboldt University of Berlin. He also held visiting professorships at universities in the United States, including the University of California, Berkeley and Stanford University.

In addition to his academic work, Kittler was also involved in various artistic and cultural projects. He collaborated with musicians and artists on multimedia installations and performances, and he was a regular contributor to German cultural magazines and newspapers.

Kittler retired from teaching in 2008 and passed away in 2011 at the age of 68. His work continues to be widely read and discussed in media studies, cultural theory, and related fields.

III. Overview of Key Ideas

At the core of Kittler’s thought is a concern with the ways in which media technologies shape and determine human consciousness, culture, and society. For Kittler, media are not simply tools or channels of communication, but rather fundamental conditions of possibility for human thought and experience.

One of Kittler’s key concepts is the notion of “discourse networks” (Aufschreibesysteme), which he develops in his book of the same name. Discourse networks, according to Kittler, are historically specific configurations of media technologies, institutions, and practices that structure the production, circulation, and reception of discourses in a given society. In “Discourse Networks 1800/1900,” Kittler analyzes the shift from the discourse network of the 18th century, centered around the medium of handwriting and the institution of the university, to the discourse network of the early 20th century, centered around the typewriter and the modern bureaucracy.

Another central theme in Kittler’s work is the idea of media as “anthropological a priori” – that is, as conditions of possibility for human existence and experience that precede and shape individual subjectivity. In works such as “Gramophone, Film, Typewriter” (1986) and “Optical Media” (2002), Kittler argues that modern media technologies such as the phonograph, film, and the computer have fundamentally transformed the way humans perceive, think, and communicate. These technologies, Kittler suggests, are not simply extensions or prostheses of the human body, but rather autonomous systems that operate according to their own logic and rules.

Kittler’s work also engages extensively with psychoanalytic theory, particularly the work of Jacques Lacan. In books such as “The Truth of the Technological World” (2013), Kittler explores the ways in which media technologies shape and structure the human psyche, arguing that the Lacanian concepts of the imaginary, the symbolic, and the real can be mapped onto different media technologies and their effects on subjectivity.

Throughout his work, Kittler emphasizes the materiality and technicality of media, challenging the notion of media as transparent or neutral conduits of information. He argues that media technologies have their own agencies and affordances that shape and constrain human possibilities in ways that are often invisible or taken for granted.

IV. Implications for Psychology, Anthropology and Media Studies

Kittler’s ideas have significant implications for a range of disciplines, including psychology, anthropology, and media studies. His analysis of the ways in which media technologies shape human consciousness and culture offers a powerful framework for understanding the psychological and social impacts of the digital age.

A. Relevance to Psychology and Trauma Treatment

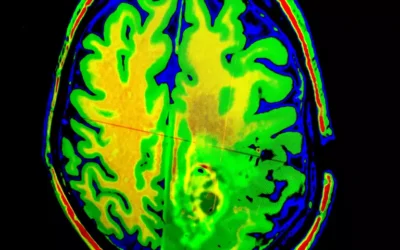

From a psychological perspective, Kittler’s concept of media as anthropological a priori raises important questions about the relationship between technology, subjectivity, and mental health. His suggestion that media technologies fundamentally structure human perception and cognition resonates with research on the cognitive and emotional effects of digital media exposure. Kittler’s work also anticipated recent debates in psychology about the impact of digital technologies on attention, memory, and social cognition.

In the context of trauma treatment, Kittler’s ideas offer a valuable perspective on the role of media and technology in shaping traumatic experiences and their aftermath. His emphasis on the materiality and technicality of media suggests that the specific technologies and platforms through which traumatic events are experienced, represented, and processed can have significant impacts on individual and collective trauma. This insight is particularly relevant in the age of social media and 24/7 news cycles, where exposure to traumatic imagery and narratives has become increasingly pervasive and immersive.

Kittler’s engagement with psychoanalytic theory also offers potential resources for thinking about trauma and its treatment. His mapping of Lacanian concepts onto different media technologies suggests that different modes of mediation may facilitate or hinder different stages of the trauma recovery process. For example, the imaginary register associated with visual media such as film and photography may be particularly relevant for the process of “bearing witness” and constructing coherent narratives of traumatic experiences, while the symbolic register associated with language and writing may be more conducive to the work of meaning-making and integration.

Depth psychologists and psychoanalysts have also drawn on Kittler’s ideas to explore the ways in which digital technologies are transforming the therapeutic process itself. For example, some have suggested that the increasing use of teletherapy and virtual reality in trauma treatment may be understood as a new kind of “discourse network” that structures the relationship between therapist and patient in novel ways. Others have used Kittler’s concept of the “body as medium” to explore how embodied experiences of trauma are mediated and processed through various technologies, from EMDR devices to biofeedback sensors.

B. Resonances with Jungian and Existential Thought

Kittler’s emphasis on the ways in which media technologies shape human existence also resonates with certain strands of Jungian and existential thought. Like Kittler, many Jungian analysts and scholars have explored the ways in which archetypal patterns and collective unconscious are mediated and expressed through various cultural technologies, from ancient myths and rituals to modern films and video games. Some have suggested that Kittler’s discourse networks may be understood as historically specific manifestations of what Jung called the “objective psyche” – the transpersonal dimension of the psyche that is shaped by collective cultural forces.

Similarly, Kittler’s critique of the autonomous subject and his emphasis on the constitutive role of technology in shaping human experience resonate with key themes in existential philosophy and therapy. Like Heidegger and other existential thinkers, Kittler challenges the notion of the self as a sovereign, self-transparent entity, emphasizing instead the ways in which human beings are always already embedded in and shaped by cultural-technological systems that exceed individual control or understanding. This perspective aligns with the existential emphasis on thrownness and facticity – the idea that human existence is fundamentally conditioned by circumstances and forces that we do not choose or control.

At the same time, Kittler’s work also points to the transformative and liberatory potential of media technologies – a perspective that resonates with the existential emphasis on transcendence and the possibility of authentic self-creation. For Kittler, as for many existential thinkers, the task is not to reject or escape technology, but rather to engage with it critically and creatively, using it to expand the horizons of human possibility and imagination.

C. Media Psychology and Historical Materialism

Kittler’s work also has important implications for the field of media psychology and for the broader project of historicizing media and technology. His approach is deeply informed by a historical materialist perspective that emphasizes the ways in which cultural and psychological phenomena are shaped by underlying technological and economic forces.

From this perspective, the psychological effects of media technologies cannot be understood in isolation from the broader social, political, and economic contexts in which they emerge and operate. Kittler’s analysis of the discourse networks of 1800 and 1900, for example, shows how the shift from handwriting to typewriting was bound up with larger transformations in the organization of labor, education, and bureaucracy in industrial capitalism.

Similarly, Kittler’s work on the history of optical media, from the camera obscura to the computer screen, traces the complex interplay between technological innovation, scientific discovery, and military-industrial imperatives. His emphasis on the role of war and militarization in driving media development challenges dominant narratives of technological progress and highlights the often violent and oppressive uses to which new media are put.

In this sense, Kittler’s work provides a valuable corrective to certain strands of media psychology that focus narrowly on the individual effects of media exposure without considering the broader cultural and political forces at work. It suggests that a truly critical media psychology must be attentive to the historical and material conditions under which media technologies emerge and evolve, and to the ways in which they are shaped by and contribute to structures of power and domination.

At the same time, Kittler’s work also points to the subversive and emancipatory potential of media technologies, particularly in the hands of artists, activists, and other cultural producers. His own collaborations with musicians and filmmakers testify to the ways in which media can be appropriated and repurposed for critical and creative ends, opening up new spaces of resistance and imagination.

V. Quotes and Passages

“Media determine our situation.” (Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, 1986)

“What remains of people is what media can store and communicate.” (Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, 1986)

“The age of media was over when, one fine day, media disappeared. In the beginning was the noise.” (Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, 1986)

“Machines take over functions of the central nervous system, and no longer, as in times past, merely those of muscles.” (Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, 1986)

“Writing itself is a technology of which literature is an effect.” (Discourse Networks 1800/1900, 1985)

“In the discourse network of 1900, it was the medium itself – the typewriter plus the phonograph or the film plus the gramophone – that had a soul.” (Discourse Networks 1800/1900, 1985)

“Technological media are models of the so-called human.” (The Truth of the Technological World, 2013)

“Computers are not about man becoming master, but about the end of man.” (Optical Media, 2002)

VI. Kittler’s Influence and Legacy

Friedrich Kittler’s work has had a profound influence on the fields of media studies, cultural theory, and the digital humanities. His provocative and often controversial ideas have inspired generations of scholars and students to rethink the relationship between technology, culture, and the human condition.

In the German-speaking world, Kittler is widely recognized as one of the founding fathers of media studies, alongside figures such as Niklas Luhmann and Jürgen Habermas. His work has been particularly influential in shaping the field of “German media theory,” which emphasizes the material and technical aspects of media over their content or symbolic dimensions.

In the Anglophone world, Kittler’s reception has been more uneven, partly due to the challenging and idiosyncratic nature of his writing and partly due to the belated translation of many of his key works. However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in Kittler’s ideas among scholars in fields such as digital media studies, software studies, and critical theory.

Kittler’s emphasis on the materiality and technicality of media has been particularly influential in shaping the field of “media archaeology,” which seeks to uncover the hidden histories and infrastructures of media technologies. Scholars such as Wolfgang Ernst, Jussi Parikka, and Lisa Gitelman have built on Kittler’s insights to develop new approaches to the study of media history and culture.

At the same time, Kittler’s work has also been critiqued for its technological determinism, its neglect of human agency and resistance, and its sometimes polemical and hyperbolic style. Some have argued that Kittler’s emphasis on the autonomy of technical systems risks effacing the social and political dimensions of media and technology, while others have questioned the historical accuracy and empirical basis of some of his claims.

Despite these criticisms, Kittler’s legacy continues to inspire and provoke scholars and students across a range of disciplines. His insistence on the need to attend to the material and technical dimensions of media, his challenge to the idea of the autonomous human subject, and his vision of media as constitutive of human existence and experience remain vital resources for thinking about the digital age and its discontents.

As we grapple with the accelerating pace of technological change and its far-reaching implications for society, culture, and the individual psyche, Kittler’s work offers a powerful reminder of the need for critical and historically informed approaches to media and technology. His ideas will undoubtedly continue to shape and inform debates in media studies, psychology, and related fields for years to come.

VIII. Kittler and the Digital Humanities

Friedrich Kittler’s work has had a significant impact on the development of the digital humanities as a field of study. His emphasis on the materiality and technicality of media, as well as his engagement with computer science and information theory, has inspired many digital humanists to rethink the relationship between technology and cultural analysis.

In particular, Kittler’s concept of “discourse networks” has been taken up by scholars working on digital archives, databases, and other computational tools for analyzing cultural texts and artifacts. His idea that media technologies fundamentally shape the production, circulation, and interpretation of knowledge has led to new approaches to data modeling, visualization, and analysis that seek to foreground the technical and material dimensions of cultural meaning-making.

At the same time, some digital humanists have also pushed back against what they see as Kittler’s technological determinism and his neglect of human agency and interpretation. They argue that while digital tools and methods can provide valuable insights into cultural phenomena, they must be used critically and reflexively, with attention to the ways in which they may reinscribe or challenge existing power relations and interpretive frameworks.

IX. Kittler and the Anthropocene

Another area where Kittler’s ideas have gained traction in recent years is in the study of the Anthropocene – the proposed geological epoch defined by the transformative impact of human activity on the Earth’s ecosystems and climate. Some scholars have drawn on Kittler’s work to argue that the Anthropocene is fundamentally a media-technological phenomenon, shaped by the invention and proliferation of fossil fuel-based technologies such as the steam engine, the internal combustion engine, and the electricity grid.

From this perspective, the ecological crisis of the present is not simply a matter of human overconsumption or resource depletion, but rather a consequence of the ways in which modern media technologies have transformed the very conditions of life on Earth. Kittler’s emphasis on the autonomy and agency of technical systems, as well as his critique of anthropocentric notions of nature and culture, resonate with recent debates about the need for a post-human or non-human politics of the Anthropocene.

At the same time, some have also criticized Kittler’s work for its apparent technological fatalism and its lack of attention to questions of environmental justice and activism. They argue that while a media-theoretical approach to the Anthropocene can provide valuable insights into the techno-ecological dimensions of the current crisis, it must be combined with a more explicitly political and ethical engagement with the uneven distribution of environmental risks and harms across different populations and regions.

XI. Kittler and the Future of Media Studies

Friedrich Kittler’s work has played a significant role in shaping the field of media studies, and his ideas continue to inspire new directions and approaches in the study of media and technology. One area where Kittler’s influence is likely to be felt in the coming years is in the study of emerging media technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things.

Kittler’s emphasis on the materiality and technicality of media, as well as his engagement with computer science and information theory, provides a valuable framework for analyzing the technical and infrastructural dimensions of these new media forms. His concept of discourse networks could be productively applied to the study of the algorithms, protocols, and standards that govern the flow of data and information in these systems, as well as the ways in which they shape new forms of subjectivity, sociality, and cultural expression.

At the same time, Kittler’s work also points to the need for a more critical and politically engaged approach to the study of emerging media technologies. His critique of the military-industrial origins and applications of many media technologies, as well as his emphasis on the ways in which they can be used for surveillance, control, and domination, remains highly relevant in an age of pervasive data collection, algorithmic governance, and digital warfare.

As media scholars grapple with these challenges, they will need to develop new theoretical and methodological tools that can account for the increasing complexity and opacity of contemporary media systems, while also attending to the ways in which they are shaped by and contribute to broader structures of power and inequality. Kittler’s work provides a valuable starting point for this project, but it will also need to be extended, critiqued, and transformed in light of the rapidly changing media landscape of the 21st century.

XII. Kittler and the Politics of Media

Another area where Kittler’s work has important implications is in the politics of media and technology. While Kittler himself was often criticized for his apparent political quietism and his lack of engagement with questions of power and resistance, his ideas have been taken up by scholars and activists seeking to develop a more critical and oppositional approach to media and technology.

In particular, Kittler’s emphasis on the military-industrial origins and applications of many media technologies has inspired a growing body of work on the surveillance, securitization, and militarization of contemporary media cultures. Scholars such as Friedrich Vogl, Lisa Parks, and Stephen Graham have drawn on Kittler’s insights to analyze the ways in which media technologies are increasingly being used for border control, policing, and warfare, as well as the ways in which they are shaping new forms of urban space and governance.

At the same time, Kittler’s work also points to the subversive and emancipatory potential of media technologies, particularly in the hands of artists, activists, and other cultural producers. His own collaborations with musicians and filmmakers testify to the ways in which media can be appropriated and repurposed for critical and creative ends, opening up new spaces of resistance and imagination.

As the politics of media and technology become increasingly central to debates about democracy, social justice, and the future of the planet, Kittler’s work offers a valuable resource for thinking about the ways in which we might contest and transform the techno-political order of the present. While his own political commitments may have been ambiguous or underdeveloped, his ideas have the potential to inspire new forms of critical theory and practice that can help us to navigate the complex terrain of media power in the digital age.

XIV. Kittler’s Place in the Canon of Media Theory

Friedrich Kittler’s work occupies a unique and significant place in the canon of media theory, alongside other influential figures such as Marshall McLuhan, Walter Benjamin, and Jean Baudrillard. Like these thinkers, Kittler sought to understand the profound ways in which media technologies shape human perception, cognition, and social relations, and to develop new theoretical and methodological tools for analyzing these effects.

However, Kittler’s approach also differs from these thinkers in important ways. Unlike McLuhan’s celebration of media as “extensions of man,” or Benjamin’s Marxian critique of the “aura” of the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, Kittler emphasizes the autonomy and agency of technical systems, which he sees as constitutive of rather than subordinate to human subjectivity and culture.

Similarly, while Baudrillard’s theory of simulation and hyperreality bears some resemblance to Kittler’s concept of the “discourse network,” Kittler’s approach is more firmly grounded in the material and technical specificities of media technologies, and less concerned with the semiotic and cultural dimensions of mediation.

In this sense, Kittler’s work represents a distinctive and valuable contribution to the field of media theory, one that challenges some of the founding assumptions and preoccupations of the discipline, while also opening up new avenues for research and analysis. By insisting on the primacy of the technical over the cultural, and by attending to the ways in which media shape the very conditions of thought and existence, Kittler pushes media theory in a more radical and provocative direction, one that continues to generate debate and inspire new scholarship.

XV. Kittler and the Future of the Humanities

Finally, Kittler’s work also has important implications for the future of the humanities more broadly. At a time when the humanities are increasingly under threat from budget cuts, disciplinary silos, and a pervasive instrumentalization of knowledge, Kittler’s insistence on the importance of engaging with the technical and material dimensions of cultural production offers a valuable counterpoint and corrective.

For Kittler, the study of literature, art, and culture cannot be separated from the study of the media technologies that make them possible. To understand a poem or a painting is to understand the material conditions of its production and circulation, from the paper and ink used to inscribe it to the institutions and networks that disseminate it.

This approach challenges traditional notions of the humanities as a realm of pure aesthetics or disinterested contemplation, and instead situates cultural artifacts within the broader contexts of technological change, economic production, and political power. By doing so, it opens up new possibilities for interdisciplinary collaboration and engagement, as humanists learn to work with engineers, computer scientists, and other technical experts to analyze the complex systems that shape our world.

At the same time, Kittler’s work also points to the ongoing relevance and value of the humanities in an age of technological acceleration and disruption. By attending to the ways in which media technologies shape human subjectivity and sociality, and by tracing the histories and genealogies of these effects, humanists can offer critical insights and interventions into the techno-political order of the present.

In this sense, Kittler’s legacy is not only to have transformed the field of media studies, but also to have challenged and enriched the humanities as a whole. As we grapple with the implications of artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and other emerging technologies, his work reminds us of the need for a critical and historically informed approach to the study of media and culture, one that can help us to understand and navigate the complex terrain of the digital age.

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

The Left and Right Hand Path in Cultural Psychology

VII. Bibliography

A. Primary Sources

Kittler, Friedrich A. “Discourse Networks 1800/1900”. Stanford University Press, 1990.

Kittler, Friedrich A. “Gramophone, Film, Typewriter”. Stanford University Press, 1999.

Kittler, Friedrich A. “Optical Media”. Polity Press, 2009.

Kittler, Friedrich A. “The Truth of the Technological World: Essays on the Genealogy of Presence”. Stanford University Press, 2013.

Kittler, Friedrich A. “Literature, Media, Information Systems: Essays”. Routledge, 1997.

Kittler, Friedrich A. “The History of Communication Media”. ctheory.net, 1996.

B. Secondary Sources

Winthrop-Young, Geoffrey. “Kittler and the Media”. Polity Press, 2011.

Parikka, Jussi. “What is Media Archaeology?”. Polity Press, 2012.

Peters, John Durham. “Kittler’s Apriori”. In “Kittler Now: Current Perspectives in Kittler Studies”, edited by Stephen Sale and Laura Salisbury, Polity Press, 2015.

Gane, Nicholas. “Friedrich Kittler: From Discourse Networks to Cultural Mathematics”. Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 23, no. 7-8, 2006, pp. 17-38.

Winthrop-Young, Geoffrey, and Ilinca Iurascu, editors. “Kittler Now: Current Perspectives in Kittler Studies”. Polity Press, 2015.

Ernst, Wolfgang. “Chronopoetics: The Temporal Being and Operativity of Technological Media”. Translated by Anthony Enns, Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

0 Comments