Executive Summary: Why Talk Therapy Can’t Cure Trauma

The Biological Reality: Trauma is not a “thought” problem; it is a “body” problem. It lives in the Subcortical Brain (the Lizard Brain), which does not speak language or understand logic.

The Disconnect: Traditional therapies like CBT target the Prefrontal Cortex (the Ego). This is like trying to put out a fire in the basement by watering the roof.

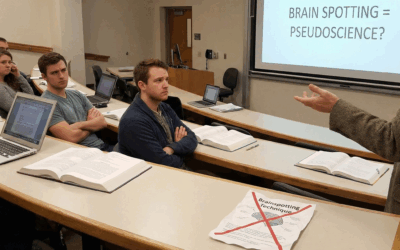

The Solution: To heal deep trauma, we must use “Bottom-Up” therapies like Brainspotting, EMDR, and Somatic Experiencing that bypass the Ego and speak directly to the nervous system.

How to Eliminate the Roots of Trauma in the Deep Brain: Moving Beyond the Ego

There are plenty of books written by doctors and scientists that explain the technical mechanics of the brain. The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk and When The Body Says No by Gabor Maté are excellent technical manuals. But in this article, we are going to take a phenomenological look at trauma. We aren’t just going to talk about neurons; we are going to talk about what it feels like to be hijacked by your own biology.

Why is it that you can understand, intellectually, that you are safe, but your heart is still pounding? Why can you “know” you are worthy, but still feel small and terrified in a meeting? The answer lies in the architecture of your brain.

The Prefrontal Cortex: The CEO of the Brain

First up is the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC). This is the front of the brain, just behind your forehead. It is responsible for personality, logic, language, and impulse control. If you were to get an ice-pick lobotomy (a dark chapter in our history), this is the part that would be severed. You would still breathe and eat, but “You”—your spark, your identity—would be gone.

We often call this the Ego. The Ego loves control. It loves stories. It wants to explain why things are happening. But here is the critical flaw: the Ego is the last part of the brain to know what is going on. It is a slow processor compared to the survival brain.

The Subcortical Brain: The Lizard in the Basement

Underneath the cortex lies the Subcortical Brain (or Brainstem/Limbic System). This is the evolutionary ancient part of us. We share this anatomy with reptiles.

A lizard does not have an ego. It does not pontificate about its relationship with a moth. When it sees a moth, it snaps. When it sees an owl, it runs. It is pure instinct, pure survival.

The Programming Problem:

Our Subcortical Brain is programmed by experience, not by words.

* If you were bitten by a dog at age 5, your Lizard Brain learned: “Dogs = Death.”

* Today, at age 30, your Prefrontal Cortex knows: “That Golden Retriever is friendly.”

* The Result: You are panic-stricken (Lizard reaction) while simultaneously telling yourself it’s irrational (Ego reaction). The Lizard always wins because it controls the adrenaline.

The Direction of Traffic: Why “Thinking” Doesn’t Work

We like to believe that we think a thought, and then have a feeling.

Thought: “I am safe.” -> Feeling: Calm.

But biology works in the opposite direction.

Body Sensation -> Subcortical Emotion -> Cortical Thought.

We feel the tightness in the chest first. Then the Limbic System interprets it as fear. Finally, the Prefrontal Cortex makes up a story to explain it (“I must be anxious about that email”).

This is why you cannot talk yourself out of a trauma response. Trauma lives upstream from the language centers. When we try to use CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) to treat deep trauma, we are trying to put out a fire in the basement by watering the roof.

Limbic Feedback: When the Past Becomes the Present

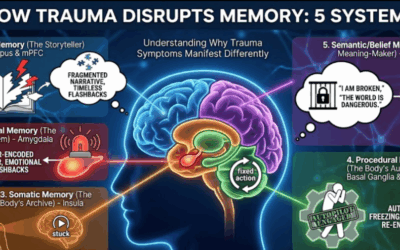

Trauma hijacks the timestamping mechanism of the brain (the Hippocampus).

Because the traumatic memory was never properly processed, the Subcortical Brain keeps it labeled as “Current Threat.”

When you are triggered, you aren’t remembering the past; you are re-experiencing it biologically. Your heart rate, muscle tension, and cortisol levels match the original event.

The Ego hates this. It feels like a loss of control. So, the Ego fights back. It says, “I shouldn’t feel this way! Stop it!” This creates an internal civil war:

* The Body: “We are dying!”

* The Ego: “Shut up, we are at Starbucks!”

This war is exhausting. It is the root of burnout and chronic fatigue.

Brain-Based Therapies: The Solution

If we cannot think our way out, we must feel our way out. We need therapies that bypass the Ego and speak directly to the Lizard.

This is where Bottom-Up Processing comes in.

1. Brainspotting

Brainspotting uses the visual field to access the subcortical brain. Where you look affects how you feel. By holding a specific eye position, we can anchor the brain in the deep processing mode, allowing the “capsule” of traumatic memory to open and release without the Ego interfering.

2. EMDR

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) uses bilateral stimulation to mimic REM sleep. It helps the brain “digest” the undigested trauma, moving it from the Limbic System to the Cortex, turning “reliving” into “remembering.”

3. Somatic Experiencing

Trauma is energy trapped in the nervous system. Somatic therapies allow the body to complete the “fight or flight” cycle that was interrupted during the trauma. This might look like shaking, crying, or pushing. It is the body finally exhaling the breath it has been holding for years.

Conclusion: Surrender the Ego

Healing requires a surrender of the Ego’s need to control. We must learn to listen to the wisdom of the body. The symptom is not the enemy; the symptom is a messenger from the Deep Brain saying, “There is something down here that needs your attention.”

When we stop fighting our own biology and start listening to it, true recovery begins.

Explore Deep Brain Therapies

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Somatic Modalities

Neuroscience of Healing

Polyvagal Theory & The Nervous System

Integrative Neuroscience of Trauma

Bibliography

- Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

- Maté, G. (2003). When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress. Vintage Canada.

- Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: The Revolutionary New Therapy for Rapid and Effective Change. Sounds True.

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. North Atlantic Books.

0 Comments