“The sense of being alive, the ability to feel real, to be genuinely spontaneous – these are the hallmarks of emotional health. And they all begin in the earliest interactions between mother and baby, in that sacred space where two beings meet and a self is born.”

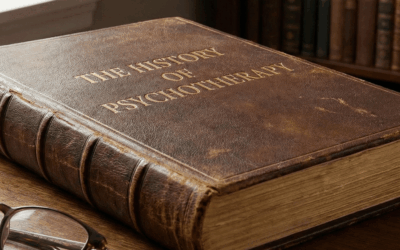

The Theories and Ideas of D.W. Winnicott

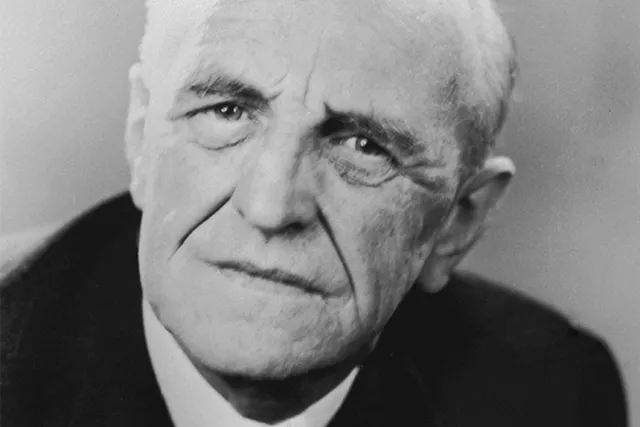

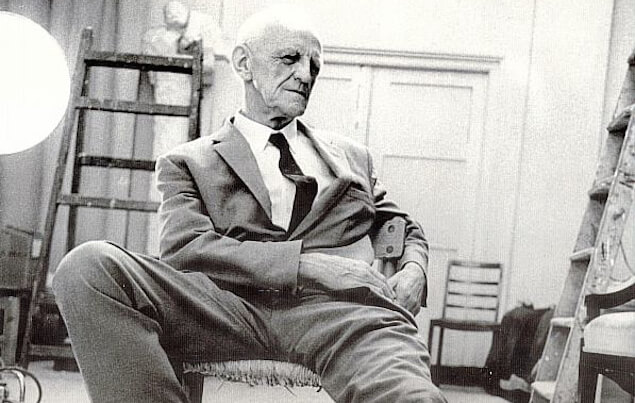

1. Who Was Donald Woods Winnicott?

Donald Woods Winnicott (1896-1971) was a pioneering British pediatrician and psychoanalyst whose innovative theories transformed our understanding of the emotional development of infants and children. Over a prolific career spanning five decades, Winnicott introduced such groundbreaking concepts as the “good-enough mother,” the “transitional object,” and the “true and false self.” His insights shed new light on the crucial role of the early caregiving environment in fostering a child’s capacity for love, creativity, and healthy independence. At the heart of Winnicott’s work was a profound respect for the wisdom of the body and the innate growth tendencies of the human psyche. This article provides an in-depth exploration of his key ideas and their enduring clinical and cultural significance.

Timeline of Life and Work

1896: Donald Woods Winnicott born in Plymouth, England, to a prosperous Methodist family

1914-1917: Studies medicine at Jesus College, Cambridge, interrupted by WWI service in the Royal Navy

1920: Completes medical training at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London

1923: Begins forty-year career at Paddington Green Children’s Hospital

1924: Starts personal psychoanalysis with James Strachey (translator of Freud)

1935: Qualifies as adult psychoanalyst; begins second analysis with Joan Riviere

1940-1945: Consultant psychiatrist for evacuated children during the Blitz

1945: Publishes “Primitive Emotional Development”

1951: “Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena” introduces his most famous concept

1958: “The Capacity to be Alone” published 1960: “The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship” establishes his mature theory

1965: “The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment” published

1971: Dies in London; “Playing and Reality” published posthumously

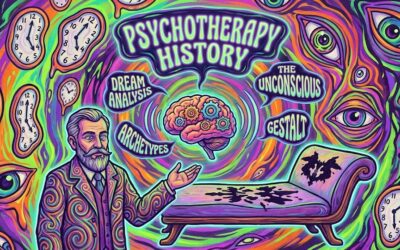

Overview of D.W. Winiccott’s Theories

Winnicott transformed psychoanalysis by shifting focus from drives to relationships, from pathology to health, from interpretation to holding. His central insight was that the self emerges not from instinctual satisfaction but from the quality of early caregiving relationships.

The Good Enough Mother:

Perhaps his most liberating concept, Winnicott argued that mothers need not be perfect but merely “good enough.” The good enough mother starts with almost complete adaptation to her infant’s needs, then gradually fails in small, manageable ways. These optimal failures allow the infant to develop a sense of self separate from mother. This challenged both the idealization and demonization of mothers prevalent in psychoanalysis.

Holding Environment:

The therapeutic relationship mirrors maternal holding, providing a safe space where the patient can regress, play, and discover their true self. The therapist’s reliability, survival of attacks, and non-retaliation create conditions for psychological growth. This is not just metaphorical but involves actual psychological containment of unbearable anxieties until the patient can manage them independently.

True Self vs. False Self:

Winnicott identified how inadequate early care forces children to develop a compliant False Self that protects the True Self from impingement. The False Self appears successful but feels empty, going through motions without genuine vitality. Therapy involves creating conditions where the True Self can emerge from hiding.

Transitional Objects and Potential Space:

The teddy bear or blanket represents the child’s first creation, neither purely internal fantasy nor external reality but existing in what Winnicott called potential space. This intermediate area between inner and outer reality becomes the location of play, creativity, and culture throughout life. Art, religion, and imagination all occupy this transitional realm.

Playing:

For Winnicott, playing is not preparation for life but the essence of health itself. “It is in playing and only in playing that the individual child or adult is able to be creative and to use the whole personality.” Psychotherapy occurs in the overlap of two play areas, therapist and patient. If the patient cannot play, the therapist’s first task is to create conditions where play becomes possible.

The Antisocial Tendency:

Rather than viewing delinquency as badness, Winnicott saw it as hope. The antisocial act represents an attempt to reclaim something good that was lost, a protest against deprivation that assumes someone cares enough to respond. This reframed acting out as communication rather than pathology.

Relevance to Psychotherapy

Winnicott’s influence on contemporary psychotherapy cannot be overstated. He humanized the therapeutic relationship, moving it from the authoritarian doctor-patient model to a collaborative, creative partnership. His concepts provide practical guidance for working with the most challenging clinical presentations.

Clinical Holding:

Therapists now understand that interpretation alone rarely heals. Sometimes patients need to be psychologically held through crises, with the therapist maintaining calm presence without rushing to fix or explain. This holding allows disintegrated states to reintegrate naturally, without forcing premature insight.

Regression in Service of the Ego:

Winnicott normalized therapeutic regression, seeing it not as resistance but as return to the point where development was derailed. By allowing patients to become dependent, even infantile, within the safe container of therapy, frozen developmental processes can restart.

Survival of Destructiveness

: When patients attack the therapist through anger, devaluation, or acting out, Winnicott saw this as healthy aggression seeking an object that can survive. The therapist who neither retaliates nor withdraws demonstrates their reality and reliability, allowing the patient to use them as a genuine other rather than a projection.

Working with Emptiness:

For patients with False Self presentations, successful careers and relationships may mask profound emptiness. Winnicott’s framework helps therapists recognize that dismantling false success to reach authentic aliveness requires courage from both parties. The therapy must provide a holding environment strong enough to contain the terror of not knowing who one really is.

The Therapeutic Frame as Potential Space:

Modern therapists understand the therapy room as potential space where play, creativity, and transformation occur. The reliability of time, place, and therapeutic presence creates a container where the unthinkable can be thought, the unspeakable spoken, the unfelt felt.

Winnicott’s radical trust in developmental processes, his faith that health emerges given proper conditions, and his emphasis on the ordinary devotion of caregivers rather than expert technique, democratized psychotherapy. He showed that healing comes not from brilliant interpretations but from providing what was missing: reliable presence, survived destructiveness, and space to play.

2. The Holding Environment and the Good-Enough Mother

Central to Winnicott’s theory was the concept of the “holding environment” – the entire matrix of physical and psychological care that the infant requires for healthy development. For Winnicott, the foundation of this environment is the “good-enough mother” – the caregiver who sensitively attunes to the baby’s needs and provides a sense of safety, consistency, and responsiveness. Through countless experiences of being held, fed, soothed, and mirrored, the infant gradually internalizes a sense of being lovable, valuable, and real.

Crucially, Winnicott emphasized that the good-enough mother is not a figure of perfection, but one who intuitively adapts to the baby’s changing developmental needs. In the earliest “absolute dependence” phase, she devotes herself to the infant’s care, creating an illusion of omnipotence. As the baby grows, she gently “disillusions” them through tolerable frustrations, allowing them to discover their separateness and the limits of their control. This “graduated failure” of adaptation is essential for the child’s growing autonomy and resilience.

3. Transitional Phenomena and the Capacity for Symbol Formation

Another of Winnicott’s key contributions was the concept of “transitional phenomena” – the special class of objects and experiences that help the child navigate the journey from absolute dependence to relative independence. The prototype of these phenomena is the “transitional object,” such as the teddy bear or blanket that the toddler adopts as a source of comfort and security. For Winnicott, these treasured possessions are not merely sentimental toys, but powerful symbols of the child’s emerging capacity for creative illusion.

In the “potential space” between self and other, fantasy and reality, the child endows the transitional object with a special aliveness and meaning. It becomes a token of the mother’s love that can be summoned in her absence, a way of coping with separation and loss. At the same time, the object represents the child’s own imaginative powers, their ability to imbue the world with personal significance. As such, it lays the foundation for all later creativity, from art and play to religion and science.

Winnicott saw transitional phenomena as crucial for healthy emotional development. They allow the child to tolerate ambiguity, to experience the paradox of creating what is already there. In the transitional realm, the child learns to play with reality, to find and fashion their own meanings. This capacity for creative illusion, Winnicott believed, is the key to a life of spontaneity, joy, and fulfillment.

4. The True and False Self

Perhaps Winnicott’s most famous concept is the distinction between the “true self” and the “false self.” For Winnicott, the true self is the vital, spontaneous core of the personality, the source of authentic feeling and desire. It emerges in the context of a holding environment that allows the infant to experience and express their own aliveness, without intrusion or demands for compliance.

In contrast, the false self is a defensive façade that the child constructs to protect the true self from a misattuned or impinging environment. When the caregiver chronically fails to meet the infant’s needs, or forces them to conform to external expectations, the child learns to suppress their own impulses and adopt a compliant, inauthentic persona. The false self is a mask of normalcy, a way of securing love and approval at the expense of real intimacy and creativity.

Winnicott saw the degree of split between the true and false self as a continuum, ranging from mild inauthenticity to severe psychopathology. In health, the false self serves as a flexible, adaptive interface with the world, while the true self remains the vital center of spontaneity and aliveness. In more serious disturbances, such as schizoid and borderline conditions, the false self takes over, leaving the individual feeling empty, unreal, and cut off from their own depths.

The therapeutic task, for Winnicott, is to help the patient rediscover and nurture their true self. This involves creating a new holding environment in the therapy, one that allows the patient to relax their defenses and experience their own authenticity. Through the therapist’s empathic attunement and non-intrusive presence, the patient can begin to “play” again, to experiment with their own thoughts, feelings, and impulses. Gradually, the true self can emerge from hiding and take its rightful place at the center of the personality.

5. Aggression, Destruction, and the Use of an Object

Winnicott’s understanding of aggression and destructiveness was another groundbreaking aspect of his theory. For Winnicott, aggression is an inherent part of the life force, the engine of growth and individuation. From birth, the infant expresses their aliveness through vigorous movements, intense cries, and eager exploration. These aggressive impulses are not inherently hostile or destructive, but a natural part of the child’s vitality and self-assertion.

However, when the environment fails to contain and survive the child’s aggressive expressions, the child may come to fear their own destructive potential. They may inhibit their spontaneity and aliveness, or turn their aggression inward in self-attack. Alternatively, they may continue to attack the environment, seeking to elicit the containment and limit-setting they need to feel safe.

For Winnicott, the capacity to use an object—to relate to others as separate, resilient beings—emerges through a process of “destroying” the object in fantasy. As the child experiments with their aggressive impulses, they come to discover that the caregiver survives their attacks without retaliating or withdrawing. This experience of the object’s “survival” allows the child to recognize their separateness, to appreciate their autonomy and resilience.

In therapy, Winnicott emphasized the importance of allowing the patient’s aggressive and destructive impulses to emerge, without retaliating or collapsing. By surviving the patient’s attacks, the therapist demonstrates their realness and their commitment to the relationship. This experience of “object usage” can be profoundly healing for patients who have never had their aggression adequately met and contained.

6. Playing, Creativity, and Cultural Experience

Throughout his work, Winnicott emphasized the vital importance of playing for emotional health and creativity. For Winnicott, play is not a frivolous pastime, but the natural medium of self-expression and growth. In play, the child explores the world, tests reality, and experiments with different ways of being. They discover their own agency, creativity, and resilience, learning to tolerate uncertainty and embrace the unknown.

Winnicott saw the capacity for play as the foundation of all later cultural experience, from art and science to religion and philosophy. In the “potential space” between self and world, the individual can engage in creative dialogue with tradition, finding their own voice and vision. Through play, we participate in the ongoing creation of meaning, contributing our own threads to the tapestry of human culture.

For Winnicott, psychotherapy itself is a form of play, a way of exploring the potential space between patient and therapist. By fostering an atmosphere of safety, trust, and spontaneity, the therapist invites the patient to rediscover their capacity for creative living. Through the mutual play of the therapeutic relationship, the patient can work through stuck patterns, try out new possibilities, and tap into their own deepest resources.

7. The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment

Winnicott’s vision of emotional development was fundamentally hopeful and growth-oriented. He saw the human being as inherently creative, driven by an innate impulse toward integration and self-realization. This “maturational process,” as he called it, unfolds in the context of a “facilitating environment” that supports and nurtures the individual’s unique potential.

At each stage of development, the facilitating environment provides the optimal conditions for growth and transformation. In infancy, it is the good-enough mother who adapts to the baby’s needs, allowing them to experience their own aliveness and creativity. In childhood, it is the family and school that provide a secure base for exploration and learning, setting clear boundaries while encouraging autonomy and initiative.

Throughout life, we continue to need facilitating environments that recognize and foster our deepest capacities. In therapy, the facilitating environment is the “holding” presence of the therapist, who creates a safe space for self-exploration and growth. In society, it is the network of supportive relationships and institutions that allow individuals to flourish and contribute their gifts.

For Winnicott, mental health is not a static state of perfection, but a dynamic process of ongoing growth and self-realization. It is the capacity to live creatively, to embrace the challenges and possibilities of each new stage. With the support of a facilitating environment, Winnicott believed, every individual has the potential to become fully alive, authentic, and uniquely themselves.

8. Implications for Psychotherapy and Beyond

Winnicott’s ideas have had a profound impact on the theory and practice of psychotherapy, as well as on our broader understanding of human development and potential. His emphasis on the early caregiving relationship, the importance of play and transitional phenomena, and the role of the facilitating environment have transformed the way we think about mental health and healing.

In the realm of psychotherapy, Winnicott’s work has inspired a wide range of approaches that prioritize the therapeutic relationship, the co-creation of meaning, and the fostering of spontaneity and authenticity. From attachment-based and relational therapies to expressive arts and play therapies, Winnicott’s ideas have provided a foundation for more humane, growth-oriented models of treatment.

At the same time, Winnicott’s insights have relevance far beyond the consulting room. His vision of the good-enough mother has influenced parenting practices and early childhood education, emphasizing the importance of attunement, responsiveness, and graduated disillusionment. His concepts of transitional phenomena and the potential space have shed light on the role of creativity and illusion in human culture, from art and religion to science and politics.

Perhaps most importantly, Winnicott’s work offers a powerful vision of human potential and resilience. In a world that often feels fragmented, uncertain, and dehumanizing, Winnicott reminds us of the transformative power of relationships, the healing potential of play and creativity, and the innate striving of every individual toward wholeness and self-realization. His ideas challenge us to create facilitating environments that nurture the true self, in all its complexity and vitality.

As we navigate the challenges of the 21st century, Winnicott’s legacy invites us to place human development and potential at the center of our endeavors. Whether as parents, therapists, educators, or policymakers, we have the opportunity to create holding environments that allow individuals to grow into their fullest, most authentic selves. By honoring the wisdom of the body, the creativity of the imagination, and the resilience of the human spirit, we can help to build a world that truly facilitates the ongoing miracle of life.

9. Winicott’s Legacy

The developmental psychology of D.W. Winnicott offers a profound and compassionate vision of human growth and potential. Through his groundbreaking concepts of the holding environment, transitional phenomena, and the true and false self, Winnicott illuminated the delicate dance of dependence and autonomy, illusion and reality, that underlies the emergence of selfhood and creativity.

At the heart of Winnicott’s work is a deep trust in the innate wisdom of the psyche, the vital spontaneity that animates all life. For Winnicott, emotional health is not a matter of perfect adaptation or conformity, but the capacity to live creatively, to play with reality, to embrace the paradoxes of existence. It is the fruit of a facilitating environment that recognizes and nurtures the true self, in all its vulnerability and resilience.

In a world that often feels fragmented, mechanistic, and alienating, Winnicott’s ideas offer a timely and urgent message. They remind us of the transformative power of relationships, the healing potential of creativity and play, and the innate striving of every individual toward integration and wholeness. They challenge us to create a culture that truly facilitates human development, one that honors the complexity and vitality of the self.

As we navigate the uncertainties of the present and the possibilities of the future, Winnicott’s legacy invites us to place human potential at the center of our concerns. Whether as parents, therapists, educators, or leaders, we have the opportunity to create holding environments that allow individuals to grow into their fullest, most authentic selves. By nurturing the true self, in all its creativity and resilience, we can help to build a world that truly supports the flourishing of life.

In this task, we have much to learn from Winnicott’s wisdom and humanity. His insights into the delicate interplay of dependence and autonomy, his respect for the spontaneity and resilience of the child, his vision of therapy as a safe space for self-discovery and growth – all of these offer valuable guideposts for our own work and lives. By engaging with Winnicott’s ideas, we can deepen our understanding of what it means to be fully alive, authentic, and creative in the world.

Ultimately, Winnicott’s greatest gift may be his unwavering faith in the human spirit, his conviction that every individual has the potential for a life of meaning, joy, and fulfillment. In a world that often feels bleak and hopeless, this message of possibility is more needed than ever. May we have the courage and compassion to carry it forward, to create a culture that truly facilitates the miracle of human development. In this lies our deepest hope for ourselves, for our children, and for the future of our world.

10. Winnicott and Intersubjectivity

In recent decades, Winnicott’s work has been increasingly recognized as a precursor to the “relational turn” in psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. His emphasis on the co-created nature of the self, his understanding of the therapeutic relationship as a new developmental experience, and his appreciation for the complex interplay of subjectivities all anticipate key themes in contemporary relational and intersubjective approaches.

For Winnicott, there is no such thing as a baby apart from the maternal care they receive. The self emerges not in isolation, but through countless moments of attunement, mirroring, and mutual regulation between infant and caregiver. This recognition of the thoroughly intersubjective nature of human development challenges the myth of the isolated, self-contained individual, highlighting the ways in which we are fundamentally constituted by our relationships.

In the therapeutic context, Winnicott’s ideas have inspired a greater focus on the co-constructed nature of the therapeutic relationship, the ways in which both patient and therapist shape and are shaped by their encounter. Rather than a one-way delivery of insight or technique, therapy is understood as a mutual process of exploration and discovery, a joint creation of new relational possibilities.

This intersubjective sensibility has important implications beyond the consulting room as well. In education, it suggests the importance of creating learning environments that foster mutual recognition, dialogue, and collaborative meaning-making. In organizations, it highlights the ways in which leadership, creativity, and productivity emerge through the complex interplay of individual and collective subjectivities. And in our wider culture, it invites us to recognize the deeply interconnected nature of our lives, the ways in which our sense of self is always embedded in webs of relationship and shared meaning.

11. Winnicott, Spirituality, and the Sense of Aliveness

While Winnicott did not explicitly write about spirituality, his understanding of emotional health and authenticity has profound spiritual implications. For Winnicott, the capacity to feel real, to experience one’s own aliveness and creative engagement with the world, is the hallmark of psychological integration and well-being. This sense of vitality and realness, he suggests, emerges through the interplay of dependence and autonomy, illusion and disillusionment, that characterizes healthy development.

In many ways, Winnicott’s vision of aliveness resonates with themes in existential and humanistic psychology, as well as in contemplative and mystical traditions. The true self that he describes – spontaneous, creative, and deeply connected to the world – echoes the “authentic self” of existential thought, the “self-actualizing tendency” of humanistic psychology, and the “true nature” or “buddha nature” of Buddhist and Hindu teachings.

For Winnicott, the capacity to feel real is not a matter of achieving some perfect state of enlightenment or individuation, but of embracing the ongoing, dynamic process of living and relating. It involves a kind of radical acceptance of oneself and the world, a willingness to engage fully with the joys and sorrows, the challenges and possibilities of existence. In this sense, Winnicott’s work points toward a deeply affirmative, life-embracing spirituality, one that finds the sacred not in some transcendent realm, but in the midst of the ordinary, the everyday, the here and now.

This understanding has important implications for psychotherapy and for our wider culture. It suggests that the goal of therapy is not simply symptom relief or behavioral change, but a deeper reconnection with one’s own aliveness, creativity, and authenticity. It invites us to create spaces – in our relationships, our communities, and our institutions – that foster this sense of vitality and realness, that allow individuals to feel deeply held and deeply free at the same time. And it challenges us to embrace a more holistic, integrative vision of the spiritual journey, one that honors the wisdom of the body, the power of play and creativity, and the transformative potential of relationship.

12. Winnicott’s Legacy and the Future of Psychology

As we have seen, D.W. Winnicott’s developmental psychology offers a rich and nuanced vision of human growth and potential. Through his innovative concepts and humane clinical sensibility, Winnicott shed new light on the subtle interplay of dependence and autonomy, creativity and constraint, that shapes the emergence of selfhood and the capacity for authentic living.

While rooted in the psychoanalytic tradition, Winnicott’s ideas have had a profound impact across a wide range of fields and disciplines. His understanding of the importance of the early caregiving environment has informed research and practice in attachment theory, child development, and parenting education. His appreciation for the role of play and transitional phenomena has influenced work in the arts, education, and occupational therapy. And his vision of the true and false self has provided a powerful framework for understanding issues of authenticity, identity, and self-realization in psychotherapy and beyond.

As we navigate the complexities and challenges of the 21st century, Winnicott’s legacy continues to offer vital insights and inspiration. In a world that often feels fragmented, uncertain, and dehumanizing, his work reminds us of the resilience and creativity of the human spirit, the transformative power of relationships, and the importance of environments that foster spontaneity, play, and authentic self-expression.

For psychologists and mental health professionals, engaging with Winnicott’s ideas can enrich our understanding of human development, psychopathology, and the process of therapeutic change. His emphasis on the co-created nature of the self, the importance of the holding environment, and the goal of emotional authenticity can inform more relationally-attuned, developmentally-sensitive, and humanistically-grounded approaches to treatment. At the same time, his appreciation for the complex interplay of the intrapsychic and the interpersonal, the individual and the social, can help us to develop more integrative, contextually-aware models of theory and practice.

More broadly, Winnicott’s vision of facilitating environments and the maturational process invites us to rethink many of our core assumptions about human development, education, and socialization. It challenges us to create families, schools, workplaces, and communities that truly support the unfolding of each person’s unique potential, that provide a “good-enough” balance of safety and freedom, attunement and disillusionment. It calls us to value the wisdom of the body, the power of play and creativity, and the deep human need for both relatedness and autonomy.

As we look to the future of psychology and the human sciences, Winnicott’s work offers a generative foundation for new directions in theory, research, and practice. By continuing to engage with his ideas, to elaborate and extend them in light of new knowledge and changing contexts, we can develop a more humane, integrative, and transformative vision of psychological science and human possibility. In this way, we can carry forward Winnicott’s profound legacy of curiosity, creativity, and care, and help to build a world that truly facilitates the full flourishing of the human spirit.

13. Winnicott and the Paradoxes of Human Existence

One of the most compelling aspects of Winnicott’s thought is his deep appreciation for the paradoxical nature of human experience. Throughout his writings, he explores the ways in which growth and creativity emerge through the tension and interplay of seemingly contradictory forces – dependence and autonomy, illusion and reality, destruction and survival, the individual and the environment.

For Winnicott, these paradoxes are not problems to be solved, but fundamental features of the human condition. The capacity to tolerate and even embrace paradox, he suggests, is a hallmark of emotional maturity and health. It allows us to navigate the complexities of life with greater flexibility, resilience, and creativity.

In the realm of early development, Winnicott highlights the paradox of the “subjective object” – the way in which the infant creates the object (the mother’s breast) that is already there. This apparent contradiction points to the co-constructed nature of reality, the way in which our experience of the world is always shaped by our own subjective needs and desires.

Similarly, Winnicott’s concept of transitional phenomena points to the paradoxical realm between inner and outer reality, between the subjectively conceived and the objectively perceived. The transitional object – the teddy bear or blanket that the child endows with special meaning – exists in an intermediate space, neither wholly internal nor wholly external. It is through playing in this space, Winnicott suggests, that we develop the capacity for creative engagement with the world.

In the therapeutic relationship, Winnicott emphasizes the paradox of “holding” – the way in which the therapist must provide a safe, supportive environment that simultaneously allows for the patient’s own spontaneous gestures and initiatives. The therapist must be both actively present and self-effacing, attuned to the patient’s needs yet respectful of their autonomy.

More broadly, Winnicott’s work highlights the paradoxical nature of the self – the way in which our sense of identity and agency emerges through a complex interplay of internal and external factors, the given and the created. We are both fundamentally dependent on others and irreducibly unique; we find ourselves through losing ourselves in play and creativity.

By embracing these paradoxes, Winnicott offers a more nuanced, dialectical vision of human development and the therapeutic process. He challenges us to move beyond simplistic dichotomies and one-sided solutions, to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty in the service of growth and transformation. In a world that often demands clear-cut answers and definitive outcomes, this capacity for paradoxical thinking is more valuable than ever.

14. Winnicott and the Politics of Mental Health

While Winnicott did not explicitly address political themes in his writings, his ideas have significant implications for how we understand and approach mental health at a societal level. His emphasis on the importance of the early caregiving environment, the role of play and creativity in human development, and the complex interplay of autonomy and dependence all challenge dominant models of mental health and illness.

In particular, Winnicott’s work calls into question the individualistic, biomedical approach that has long dominated psychiatry and clinical psychology. Rather than locating the sources of psychological distress solely within the individual brain or psyche, Winnicott highlights the crucial role of the social environment in shaping mental health outcomes. From the earliest experiences of holding and handling to the ongoing provision of facilitating environments, our psychological well-being is profoundly influenced by the quality of our relationships and the contexts in which we live.

This recognition has important implications for how we conceptualize and address mental health issues at a policy level. It suggests that promoting psychological wellness is not simply a matter of providing individual therapy or medication, but of creating social conditions that foster healthy development, creativity, and authentic self-expression. This might include investments in early childhood education, parenting support, arts and humanities programs, and initiatives to reduce poverty, discrimination, and other forms of structural violence.

At the same time, Winnicott’s ideas challenge the stigmatization and pathologization of mental distress that still pervade much of our culture. By emphasizing the continuity between health and illness, the universality of the maturational process, and the creative potential of the unconscious, Winnicott helps to normalize and humanize the full range of psychological experience. He reminds us that struggles with authenticity, dependency, and destructiveness are not signs of personal failure or defect, but inherent challenges of the human condition.

In this sense, Winnicott’s work supports a more compassionate, contextually-sensitive approach to mental health – one that recognizes the complex interplay of individual, relational, and societal factors in shaping psychological outcomes. It calls for a greater appreciation of the diversity of human experience, a more nuanced understanding of the developmental origins of distress, and a commitment to creating environments that truly support the flourishing of all individuals.

As we grapple with the mental health crises of our time – rising rates of depression, anxiety, addiction, and suicide – Winnicott’s insights are more relevant than ever. By integrating his developmental perspective into our clinical practices, our educational systems, our social policies, and our cultural narratives, we can work towards a more humane, holistic, and liberatory approach to mental health and well-being.

15. Winnicott and the Art of Living

Ultimately, perhaps, the greatest significance of Winnicott’s work lies in its profound implications for the art of living itself. More than just a theory of development or a set of therapeutic techniques, Winnicott’s ideas offer a rich, nuanced vision of what it means to be fully alive, authentically engaged, and creatively responsive to the world.

At the heart of this vision is a deep respect for the wisdom and resilience of the human psyche, the innate drive towards growth, integration, and self-realization. For Winnicott, the task of living is not to conform to some external standard of normality or success, but to become more fully oneself – to embrace one’s own spontaneity, vitality, and creativity in the face of life’s challenges and possibilities.

This is not a solitary or self-centered pursuit, but one that is fundamentally relational and contextual. As Winnicott reminds us, we become ourselves through others – through the countless moments of attunement, mirroring, and holding that shape our earliest experiences, and through the ongoing dance of autonomy and dependence that characterizes our lives. To live well is to find a way of being that honors both our need for connection and our capacity for solitude, both our vulnerability and our resilience.

Crucially, this way of being is not a static state to be achieved, but an ongoing, dynamic process – a continual unfolding and transforming in response to the changing circumstances of our lives. It requires a kind of radical acceptance of the paradoxical nature of existence, a willingness to embrace both joy and sorrow, love and loss, creation and destruction. It means learning to play in the potential spaces of our lives, to find meaning and beauty in the midst of uncertainty and imperfection.

In a world that often feels fragmented, anxious, and alienating, Winnicott’s vision of the good life offers a powerful source of hope and inspiration. By reminding us of the transformative power of relationships, the healing potential of creativity and play, and the deep human capacity for growth and resilience, he invites us to reclaim a sense of wholeness, vitality, and connection in our lives.

For those of us called to the helping professions – as therapists, educators, social workers, or healthcare providers – Winnicott’s ideas are particularly valuable. They challenge us to create spaces of holding and facilitation, environments that foster the unfolding of each person’s unique potential. They call us to a deeper attunement to the rhythms and paradoxes of the human experience, a greater respect for the wisdom of the body and the imagination. And they remind us that our own authenticity, creativity, and capacity for play are crucial resources in our work.

But Winnicott’s wisdom is not just for professionals. It is for all of us who seek to live more fully, love more deeply, and contribute more meaningfully to the world around us. By engaging with his ideas, we can enrich our relationships, enliven our work, and deepen our sense of purpose and possibility. We can learn to embrace the creative challenges of existence with greater courage, compassion, and curiosity.

As we navigate the uncertainties and opportunities of our rapidly changing world, Winnicott’s legacy offers an enduring invitation to the art of living well. May we have the vision and humanity to take up this invitation, to create a world that truly fosters the flourishing of the human spirit in all its wondrous diversity and potential. In this, lies our greatest hope for ourselves, for our communities, and for the generations to come.

0 Comments