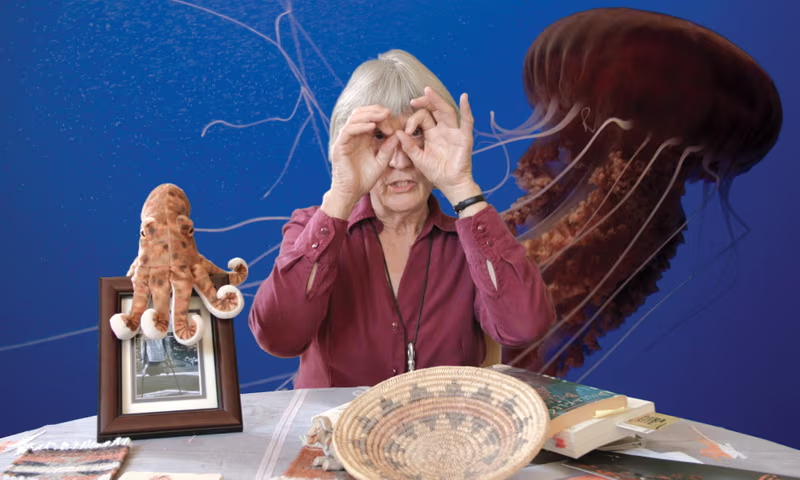

I. Who is Donna Haraway

Donna Haraway (b. 1944) is a prominent American scholar known for her groundbreaking contributions to the fields of science and technology studies, feminist theory, and cultural studies. Haraway’s interdisciplinary approach, which draws from biology, philosophy, critical theory, and the history of science, has reshaped contemporary understandings of the complex relationships between humans, animals, and machines. Her influential works, such as “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1985) and “Simians, Cyborgs, and Women” (1991), have challenged traditional boundaries between nature and culture, human and non-human, and the physical and the virtual, offering a provocative vision of a post-gender, technologically mediated world.

This paper explores the life and ideas of Donna Haraway, situating her thought within the context of late 20th-century debates around feminism, technoscience, and the politics of knowledge production. By engaging with Haraway’s key concepts, such as the cyborg, situated knowledges, and companion species, and considering their implications for fields such as psychology, anthropology, and cultural studies, this paper seeks to illuminate the enduring relevance of Haraway’s work for navigating the complexities of the contemporary technoscientific landscape.

II. Biography of Donna Haraway

Donna Jeanne Haraway was born in 1944 in Denver, Colorado. She received her undergraduate degree in zoology and philosophy from the Colorado College in 1966 and her Ph.D. in biology from Yale University in 1972. After completing her doctorate, Haraway taught at the University of Hawaii and Johns Hopkins University before joining the History of Consciousness program at the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1980, where she became a distinguished professor emerita.

Throughout her career, Haraway has been a leading figure in feminist science studies and cultural theory. Her early work focused on the history and philosophy of biology, particularly the ways in which scientific knowledge is shaped by social and political factors. In the 1980s, Haraway began to develop her theory of the cyborg, a hybrid figure that blurs the boundaries between human and machine, nature and culture. This work, exemplified by her influential essay “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1985), argued for the liberatory potential of technology and the need for new forms of feminist politics in the age of technoscience.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Haraway’s work expanded to encompass a wide range of topics, from primatology and animal studies to environmentalism and multispecies ethnography. Her book “Simians, Cyborgs, and Women” (1991) explored the historical and cultural interconnections between primates, humans, and machines, while “The Companion Species Manifesto” (2003) proposed a new ethics of human-animal relations based on co-evolution and kinship. Throughout her work, Haraway has sought to challenge dominant narratives of scientific objectivity and technological progress, emphasizing the need for situated, embodied, and accountable forms of knowledge production.

III. Overview of Key Ideas

At the heart of Donna Haraway’s thought is a critical engagement with the politics of technoscience and a vision of feminist politics that embraces the emancipatory potential of technology while remaining attuned to its risks and limitations. Haraway’s work is characterized by a rejection of rigid dualisms and essentialist categories, advocating instead for a view of the world as a complex web of material-semiotic relations and partial connections.

One of Haraway’s most influential concepts is the figure of the cyborg, which she develops in her essay “A Cyborg Manifesto.” For Haraway, the cyborg represents a new kind of political identity and agency that emerges from the fusion of human and machine, nature and culture. Rejecting both technophobic feminism and uncritical technophilia, Haraway argues that the cyborg offers a way to subvert traditional gender roles and challenge the logic of patriarchal domination. At the same time, she acknowledges the ambivalence of the cyborg as a figure of both liberation and oppression, highlighting the need for a critical and situated engagement with technology.

Another key concept in Haraway’s work is the idea of situated knowledges. In contrast to traditional notions of scientific objectivity, which assume a view from nowhere, Haraway argues for a view of knowledge as always partial, embodied, and located within specific historical and cultural contexts. For Haraway, all knowledge claims are inherently political and shaped by the social positions and interests of those who produce them. This perspective challenges the authority of dominant scientific discourses and opens up space for alternative ways of knowing, particularly those grounded in the experiences and struggles of marginalized groups.

In her later work, Haraway has expanded her focus to include the relations between humans and other species, particularly in the context of environmental crisis and technoscientific innovation. In “The Companion Species Manifesto,” she proposes a new ethics of multispecies co-evolution and kinship, challenging the anthropocentric assumptions of Western humanism. For Haraway, the key to surviving and thriving in the Anthropocene is to cultivate new forms of symbiosis and reciprocity with non-human others, recognizing our shared vulnerability and interdependence.

Throughout her work, Haraway emphasizes the importance of storytelling and speculative fabulation as tools for imagining alternative futures and resisting dominant narratives of progress and domination. Her writing is characterized by a playful and ironic style that blends critical theory with science fiction, poetry, and personal reflection. By blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction, nature and culture, human and non-human, Haraway seeks to open up new possibilities for thought and action in the face of the complex challenges of the contemporary world.

IV. Implications for Psychology, Anthropology and Cultural Studies

Donna Haraway’s ideas have significant implications for a range of disciplines, including psychology, anthropology, and cultural studies. Her critique of scientific objectivity and her emphasis on the situatedness of knowledge challenge traditional approaches to research and theory, while her vision of a post-gender, technologically mediated world opens up new possibilities for understanding identity, embodiment, and social relations.

A. Relevance to Psychology

Haraway’s work has important implications for the field of psychology, particularly in relation to questions of identity, embodiment, and technologically mediated experience. Her concept of the cyborg challenges traditional notions of the stable, autonomous self, suggesting instead a view of subjectivity as fluid, hybrid, and constituted through networks of material-semiotic relations. This perspective resonates with recent developments in posthumanist psychology and critical neuroscience, which emphasize the role of technology and culture in shaping the brain and behavior.

Haraway’s ideas are also relevant to the study of trauma and its treatment. Her emphasis on the situatedness of knowledge and the importance of embodied experience suggests a view of trauma as deeply embedded within specific historical, cultural, and political contexts. This perspective challenges individualistic and pathologizing approaches to trauma, instead highlighting the need for collective and systemic interventions that address the structural conditions of violence and oppression.

Haraway’s work also intersects with depth psychology and Jungian approaches to the unconscious. Like Jung, Haraway emphasizes the role of myth, metaphor, and archetype in shaping human experience and identity. However, while Jung tended to view archetypes as universal and timeless structures of the psyche, Haraway sees them as historically and culturally specific “figurations” that are constantly being reworked and reinvented in response to changing social and technological conditions. This perspective opens up new possibilities for understanding the collective unconscious as a dynamic and contested space, shaped by the interplay of cultural imaginaries and material realities.

B. Relevance to Anthropology

Haraway’s work also has significant implications for the field of anthropology, particularly in relation to questions of nature, culture, and technoscience. Her critique of the nature-culture divide challenges traditional anthropological distinctions between “primitive” and “civilized” societies, suggesting instead a view of all cultures as always already technologically mediated. This perspective resonates with recent work in anthropology that emphasizes the co-production of nature and culture, the agency of non-human actors, and the political dimensions of scientific knowledge.

Haraway’s concept of companion species is particularly relevant to anthropological studies of human-animal relations. Her emphasis on the co-evolution and mutual constitution of humans and other species challenges anthropocentric assumptions about human exceptionalism and dominance over nature. Instead, Haraway proposes a view of humans as always already entangled with other species in complex webs of kinship, care, and responsibility. This perspective opens up new possibilities for multispecies ethnography and the study of interspecies relations in contexts of environmental crisis and technoscientific innovation.

Haraway’s ideas also intersect with the anthropological study of technoscience and its cultural and political dimensions. Her concept of situated knowledges emphasizes the need for a reflexive and critical approach to scientific knowledge production, one that takes into account the social positions and interests of researchers and the power dynamics that shape the production and circulation of knowledge. This perspective is particularly relevant to studies of scientific controversies, public understanding of science, and the politics of expertise in contexts of globalization and neoliberalism.

C. Relevance to Cultural Studies

Finally, Haraway’s work has important implications for the field of cultural studies, particularly in relation to questions of power, identity, and resistance in the context of technoscience and globalization. Her concept of the cyborg has become a key figure in cultural studies, representing the blurring of boundaries between human and machine, nature and culture, and the possibilities for new forms of political agency and resistance in the face of oppressive social and technological systems.

Haraway’s emphasis on storytelling and speculative fabulation as tools for imagining alternative futures resonates with recent work in cultural studies that emphasizes the role of popular culture and science fiction in shaping public understanding of science and technology. Her writing style, which blends critical theory with poetic and personal reflection, has also been influential in shaping new forms of cultural criticism and theory that challenge traditional academic genres and disciplines.

Haraway’s critique of dominant narratives of progress and her vision of a post-gender, multispecies world also intersects with cultural studies’ engagement with questions of identity, difference, and social justice. Her work challenges essentialist and binary understandings of gender, race, and sexuality, emphasizing instead the fluid and hybrid nature of identity and the need for new forms of solidarity and coalition-building across differences. This perspective is particularly relevant to studies of digital culture, social media, and the politics of representation in the context of globalization and neoliberalism.

V. Quotes and Excerpts

“A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction.” (Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto”)

“The cyborg is a kind of disassembled and reassembled, postmodern collective and personal self. This is the self feminists must code.” (Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto”)

“Feminist objectivity means quite simply situated knowledges.” (Haraway, “Situated Knowledges”)

“The knowing self is partial in all its guises, never finished, whole, simply there and original; it is always constructed and stitched together imperfectly, and therefore able to join with another, to see together without claiming to be another.” (Haraway, “Situated Knowledges”)

“Cyborgs are not reverent; they do not re-member the cosmos. They are wary of holism, but needy for connection – they seem to have a natural feel for united front politics, but without the vanguard party. The main trouble with cyborgs, of course, is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism. But illegitimate offspring are often exceedingly unfaithful to their origins. Their fathers, after all, are inessential.” (Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto”)

“The cyborg is resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence.” (Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto”)

“By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs.” (Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto”)

“Cyborg writing is about the power to survive, not on the basis of original innocence, but on the basis of seizing the tools to mark the world that marked them as other.” (Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto”)

“The ties through which companion species are knotted together matter; the details matter; the kind of web matters; the kinds of knots and loops and fraying ends matter.” (Haraway, “The Companion Species Manifesto”)

“There are no pre-constituted subjects and objects, and no single sources, unitary actors, or final ends. In Judith Butler’s terms, there are only ‘contingent foundations’; bodies that matter are the result.” (Haraway, “Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan Meets_OncoMouse”)

VI. Connections with Other Thinkers

Haraway’s work is in dialogue with a wide range of thinkers and intellectual traditions. Some key connections include:

- Feminist theory: Haraway’s work is deeply influenced by feminist scholars such as Simone de Beauvoir, Audre Lorde, and Adrienne Rich, who challenge patriarchal notions of gender and advocate for an intersectional approach to feminist politics.

- Science and technology studies: Haraway’s critique of scientific objectivity and her emphasis on the social and political dimensions of technoscience resonates with the work of scholars such as Bruno Latour, Sheila Jasanoff, and Andrew Pickering.

- Posthumanism: Haraway’s vision of a post-gender, multispecies world intersects with the work of posthumanist thinkers such as N. Katherine Hayles, Rosi Braidotti, and Cary Wolfe, who challenge anthropocentric notions of the human and advocate for new forms of relationality and ethics.

- Marxism and critical theory: Haraway’s critique of capitalism and her emphasis on the material conditions of knowledge production draw on Marxist and critical theory traditions, particularly the work of the Frankfurt School and thinkers such as Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse.

- Postcolonial and decolonial theory: Haraway’s critique of Western humanism and her emphasis on the situatedness of knowledge resonate with postcolonial and decolonial thinkers such as Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak, and Walter Mignolo, who challenge Eurocentric notions of universality and advocate for the epistemic diversity of the Global South.

VII. Haraway’s Relevance in Light of Recent Trends

Donna Haraway’s ideas remain highly relevant in light of recent trends in technology, media, and culture. Her vision of a cyborg world, in which the boundaries between human and machine are increasingly blurred, has become increasingly prescient with the rise of artificial intelligence, robotics, and the Internet of Things. Haraway’s emphasis on the need for a critical and situated engagement with these technologies, one that takes into account their social and political implications, is more important than ever in a world where algorithms and data are reshaping every aspect of our lives.

Haraway’s critique of dominant narratives of progress and her vision of a multispecies, post-gender world also resonate with recent debates around the Anthropocene, climate change, and the need for new forms of ecological thought and practice. Her emphasis on the co-evolution and interdependence of humans and other species challenges the anthropocentric assumptions of much of Western culture and opens up new possibilities for rethinking our relationship to the natural world.

At the same time, Haraway’s work remains highly relevant to ongoing struggles for social justice and political transformation. Her emphasis on the importance of situated knowledges and the need for new forms of solidarity and coalition-building across differences is particularly urgent in a world where the rise of right-wing populism and the backlash against feminism and antiracism threaten to roll back hard-won gains. Haraway’s vision of a cyborg politics, one that embraces irony, partiality, and the power of storytelling, offers a compelling model for resistance and social change in the face of these challenges.

In this sense, Haraway’s work can be seen as both a diagnosis of the present moment and a call to action for the future. By challenging us to rethink the boundaries between human and machine, nature and culture, self and other, Haraway opens up new possibilities for imagining and enacting a more just and sustainable world. As she writes in “A Cyborg Manifesto,” “The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust.” In embracing the cyborg as a figure of possibility and hope, Haraway invites us to dream of a world beyond innocence and origin, one in which we might find new ways of living and being together in the ruins of the present.

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

The Left and Right Hand Path in Cultural Psychology

VIII. Bibliography

Haraway, D. (1985). “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century”. Socialist Review, no. 80.

0 Comments