The Paradox of the Egoless Egoist

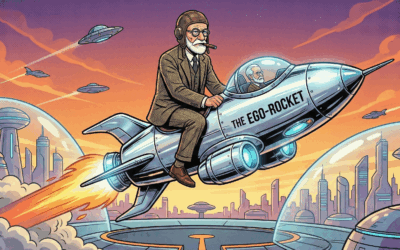

James Hillman spent decades railing against the ego and the ego-Self axis, calling it a “monotheistic ideal” that stifled psychic life. Yet as many Jungians have pointed out, by throwing away this fundamental structural principle, Hillman’s own ego simply went underground, becoming unconscious and inflating to messianic proportions. The man who rejected the ego became, paradoxically, one of the most egomaniacal figures in post-Jungian psychology: a brilliant rebel whose intellect couldn’t save him from himself.

This is the central irony of Hillman’s career. In attempting to liberate psychology from what he saw as the tyranny of ego-consciousness and the unifying Self, he became a living demonstration of why these structures matter. Without the ego-Self axis to provide grounding and orientation, Hillman was possessed by the very archetypal forces he claimed to champion, particularly the trickster. He remained always the outsider, always railing against authority, always convinced he alone saw through everyone else’s illusions.

The Trickster’s Dance: Brilliance Without Boundaries

Hillman was, without question, drop-dead brilliant. His early work crackles with insight, and his ability to deconstruct psychological orthodoxy was unmatched. As David Tacey observed during his three years working with Hillman in Texas, the man was a huge fish in a puddle for a time, attracting intellectuals and seekers hungry for something beyond conventional Jungian thinking. His critiques of ego psychology, developmental thinking, and the medicalization of the psyche remain valuable contributions.

But intellect alone doesn’t provide psychological grounding. Hillman’s complete enmeshment with the trickster archetype meant he couldn’t stop rebelling. He couldn’t build, only tear down. He spent far more time telling other people what they were doing wrong with psychology than articulating a coherent technique, map, or method for what he claimed everyone should be doing instead.

Tacey recounts a revealing moment from his analysis with Hillman. When he asked why everything they did seemed purely Jungian despite Hillman’s claims to have transcended Jung, Hillman admitted: “I haven’t yet developed a practice in line with my theory.” This stunning confession reveals the hollow core at the heart of Hillman’s project. Even his own analysands reported that in the consulting room, Hillman was practicing orthodox Jungian analysis because he didn’t actually know how to practice Hillmanian archetypal psychology. He never figured it out.

The Mythopoetic Confusion: Soul Without Structure

Hillman desperately wanted to capture the energy and authenticity of the mythopoetic men’s movement, that raw, imaginal, embodied engagement with archetypal masculinity that Robert Bly and others were facilitating. He saw in this movement a living example of what psychology could be: poetic, passionate, polytheistic, free from the constraints of systematic theory. But he fundamentally failed to figure out how to translate this into either a coherent psychotherapeutic context or a phenomenological map of what therapy should look like.

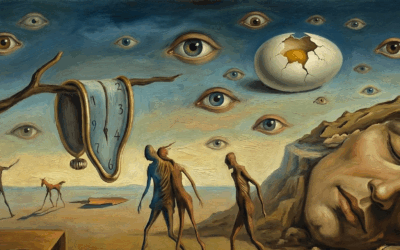

The mythopoetic work had structure, even if implicit: initiatory patterns, elder-youth relationships, contained ritual space. Hillman wanted the poetry without the container, the multiplicity without the organizing principle. He mistook the long dark night of the soul FOR the soul itself, as if perpetual dissolution and fragmentation were the goal rather than a phase in a larger process of transformation.

Tacey notes that Hillman joined up with Robert Bly precisely because “Robert Bly trades on the father wound,” the same wound that drove so much of Hillman’s own psychology. But their collaboration led to some of Hillman’s worst excesses, including his book “A Terrible Love of War”. Hillman had gone to a peace conference in the 1980s and given a talk about the need for war, prompting poet Denise Levertov to ask how he dared come to a peace conference to talk about the virtues of war.

The Polytheistic Prison: When Multiple Perspectives Become Chaos

In his middle and later periods, Hillman became what Tacey calls “a hardcore Platonic polytheist,” insisting that the Self was a “monotheistic” concept that oppressed the natural polytheism of the psyche. He wanted us to honor multiple gods, multiple perspectives, multiple realities, without any organizing principle to hold them together. But without the Self as an organizing center, what Hillman offered wasn’t liberation but fragmentation.

This theoretical move lost him the therapists, who needed practical ways to help real people with real suffering. It also lost him the various intellectual and academic communities that had been paying attention. Philosophy departments weren’t interested in his amateur Platonism. Religious studies scholars found his polytheism romantically naive. And Jungians increasingly saw him as having abandoned the core insights that made analytical psychology therapeutically effective.

David Tacey points out a crucial distinction: what Hillman was doing was not really post-Jungian at all, but rather pre-Jungian. He was regressing to the chaos before Jung’s careful differentiation of psychological structures. Without the ego-Self axis, without developmental understanding, there was no way to distinguish between creative multiplicity and psychotic fragmentation, between regression and regeneration.

Metaphysics Metaphysicians

Hillman believed that Jung’s move toward concepts such as unus mundus, the psychoid, and synchronicity took psychology beyond its rightful domain of the soul and its images and into speculative metaphysics. I sort of get this. I know all the modern theories about metaphysics in psychotherapy as well as the Jungian ones. The old joke is that with enough obsession any psychotherapy can become a metaphysics. Wilhelm Reich turned Freudian psychology into one and got into a fight with Einstein about it. This is likely why Einstein was polite but distant the next time he met another metaphysical psychologist (Carl Jung) at a dinner parties with designs on the ultimate destination of math. Maybe there are microtubules in the brain that are responsible for quantum phenomenon and maybe not. I feel like we are not just meat computers, but why write just another guys opinion about that. Science is at least another 50 years away from even guessing at this and the only real tools we have are subjectivity and informed speculation. These pathways get you too close to the creeping delusions of shadowed intuition, the oceanic longing Freud mentioned, and the literalization of magic and the sacred. These theories don’t interest me either. I want to find the most effective way to act on history that I will actually witness or predict and do that now, as an intuitive. So did Hillman.

For Hillman, psychology should remain grounded in the, inherently subjective, phenomenology of the psyche; in the lived and imaginal experiences of soul; rather than trying to explain how psyche and matter are connected in a metaphysical sense. Jung, by contrast, sought to construct a bridge between the subjective and objective worlds, speculating on how the inner and outer might be united in a single underlying reality. Hillman resisted this impulse toward metaphysical unification. He preferred to stay within the poetic and imaginal, seeing the world as ensouled through perception and image rather than through cosmological explanation.

This tension reveals an important paradox in Hillman’s work. He passionately affirmed the anima mundi, or world soul, seeing gods and archetypes in every aspect of life including cities, politics, art, and culture. Yet he rejected Jung’s theoretical framework that could explain how psyche and world might truly be connected. Jung’s speculative metaphysics, though daring, provided a model for how the world could be alive and psychically continuous with human consciousness. Hillman wanted us to see soul in things without appealing to metaphysical mechanisms. In effect, he wanted the poetry of an ensouled world without the philosophy that would justify it.

This difference can be stated more directly: Jung made religion into a science, while Hillman made science into a religion. Jung attempted to give spiritual experience empirical legitimacy through the study of symbols, archetypes, and synchronicity. He sought to render the numinous scientifically intelligible. Hillman rejected empirical psychology and turned inward to soul and imagination, elevating them into matters of devotion. His psychology became a kind of aesthetic faith that required belief in images and imagination without empirical or metaphysical proof. Where Jung tried to make the irrational rational, Hillman made the rational poetic.

This leads to a deeper structural critique. Jung’s system preserved the ego–Self axis, a relationship that anchored the ego within the wider totality of the psyche and protected against inflation or identification with archetypal contents. His concept of the psychoid served as a careful bridge between psyche and matter, maintaining differentiation even amid unity. Hillman, however, rejected these structural safeguards. By dissolving psychology into a field of autonomous images and archetypes, he risked eroding the boundaries that Jung believed were necessary for psychological balance. Without the ego–Self axis, Hillman’s vision of psyche verges on what Erich Neumann called ouroboric incest, a regression into undifferentiated unity in which the ego is swallowed by the archetypal and the imaginal.

In this light, Jung’s metaphysical speculations appear less reckless than Hillman supposed. They were, in a sense, safeguards that attempted to articulate how the world might be alive without losing the discriminating consciousness that perceives it. Hillman’s poetic psychology, while rich and evocative, seeks immersion in the imaginal without the structural or metaphysical grounding that would prevent soul from collapsing back into psychosis.

The Economics of Rebellion: When Ideology Meets Reality

For most of his career, Hillman wrote for a tiny market of intellectuals, and ideological ones at that. Tacey observed that Hillman “kept saying to me he had no superannuation” and desperately wanted more money, watching as his students like Thomas Moore sold millions of copies of books like “Care of the Soul” while Hillman’s dense, philosophical works remained accessible only to those with “two or three degrees” and the educational background to understand them.

It wasn’t until late in life, when his book “The Soul’s Code” was featured on Oprah, that Hillman finally made real money. The irony is palpable: the man who rejected popular psychology’s simplifications finally found financial success by packaging his ideas for mass consumption. By this time, according to his biographer Dick Russell, Hillman had begun to cool off considerably, perhaps finally able to relax the constant rebellion that had driven him for decades.

The Red Book Reconciliation: Too Little, Too Late?

Dick Russell’s three part biography of Hillman’s life describes how Hillman’s encounter with Jung’s Red Book in 2009 led to a surprising reconciliation with the father figure he’d spent his career rejecting. The Red Book revealed a Jung that Hillman could recognize: imaginal, visionary, poetic, immersed in images without systematic overlay. His posthumously published dialogues with Sonu Shamdasani in “Lament of the Dead” (2013) show Hillman finally appreciating that Jung’s early practice “presaged where he was seeking to move psychology.”

One of my favorite observations in Dick Russel’s work is that MANY depth psychologists come from port towns where they see wriggling creatures dragged from the depths. This coastal proximity gives rise to the interest in the forces beneath conscious awareness. It is my belief that in the Red Book Hillman finally dealt with his loneliness and let go of his brilliance. He encountered the bottom of the ocean he was searching for and found company. But this late-life recognition came after decades of theoretical damage. Hillman had already convinced a generation of his wayward Jungian followers to abandon the Self, to reject developmental thinking, to mistrust any organizing principle in the psyche. He had created what David Tacey astutely identified not as a post-Jungian psychology but as a pre-Jungian one: a regression to the chaos before Jung’s careful differentiation of psychological structures.

The Soul’s Code: Mainstream Success and Its Hollow Victory

In 1996, Hillman finally achieved the mainstream recognition and financial success he had craved with “The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling.” The book’s central concept, the “acorn theory,” proposed that each person carries a unique daimon or calling from birth, an innate image that defines their destiny. When Oprah Winfrey featured the book and had Hillman as a guest, it became a bestseller, providing him with the financial security he had long sought.

Yet the daimon theory that brought Hillman fame falls apart under scrutiny. It romanticizes a dangerous passivity toward unconscious forces, treating them as wise guides rather than potentially destructive energies requiring conscious discrimination. Our evolution filled us with forces that we developed and ego to discriminate against. Hillmans approach seems almost like a devolution. He mapped descent to something, but not return. The theory assumes these forces are inherently benevolent and purposeful, ignoring how unconscious complexes can lead us astray. Including the historical great men in the book that Hillman is content to project on. Most tellingly, when we apply Hillman’s own theory to his life, we see not the flowering of a wise daimon but the possession by a rebellious trickster archetype that he never learned to consciously relate to. As Robert Moore absurved, “These forces want ALL of you because they think they ARE you”.

Hillman loved to quote W.H. Auden’s line, “We are lived by forces we pretend to understand,” treating it as a prescription for living rather than the warning it actually represents. This fundamental misreading reveals Hillman’s core error: he confused surrender to unconscious forces with psychological sophistication. Being different is not an identity or point of pride; it’s a choice we should make consciously in specific situations where authenticity and the situation warrant it. Hillman, however, made rebellion his permanent stance, never examining where his trickster energy helped and where it harmed both himself and others.

Jung warned specifically against becoming what he called those “pernicious gadflies” who become mere mouthpieces for the unconscious, people who “identify with the unconscious and its figures” and thereby “lose all capacity for self-criticism.” These individuals, Jung observed, become inflated channels for archetypal forces, mistaking possession for wisdom. They may be “somewhat entertaining” as provocateurs, but they lack the ego strength to mediate between conscious and unconscious, between collective forces and individual responsibility.

This describes Hillman’s trajectory perfectly. Rather than developing a conscious relationship with the trickster archetype that drove him, he gave himself over to it completely. He never developed the discrimination to know when rebellion served growth and when it was merely destructive contrarianism. His appearance at a peace conference to advocate for war, his inability to create a workable clinical practice, his jealousy toward more successful students, all demonstrate someone who had become, in Jung’s terms, a gadfly rather than a guide.

The irony is crushing: the very mainstream success of “The Soul’s Code” validated a theory that, when applied to Hillman’s own life, reveals not the wisdom of following one’s daimon but the danger of unconscious possession. His daimon theory encouraged others to trust forces they didn’t understand, when his own career demonstrated the necessity of conscious discrimination in relating to these forces. The book that finally brought him fame was perhaps his most dangerous contribution, wrapping the abdication of conscious responsibility in the appealing package of destiny and calling.

The Abandoned Project: Archetypal Psychology’s Demise

Today, Pacifica Graduate Institute is essentially the only place that claims to still practice Hillmanian archetypal psychology, and even there it’s heavily diluted and integrated with other approaches. Andrew Samuels, in his revised schema of post-Jungian schools, considers the archetypal school to have “ceased to exist” or been “integrated or eliminated as a clinical entity.”

Tacey provides perhaps the most damning evidence of archetypal psychology’s failure: in all of Hillman’s 24 books, there is not a single case study of him actually practicing archetypal psychology. The absence speaks volumes. Hillman could theorize brilliantly about what was wrong with everyone else’s approach, but he couldn’t demonstrate what his alternative would look like in practice. The unintegrated person believes something to be absolutely true that they are not able to demonstrate in their life, their therapy or their soul. Hillman wasn’t angry at psychology, he was angry at himself. As poignantly as he wrote, Hillman was trying to explain something he hadn’t realized or discovered. Again, I cant fault him here, and I have mentioned that many of his vices are my own.

Perhaps most disturbingly, Hillman ended up yelling on right-wing talk radio, as Tacey confirms, ranting about how we’ve had a hundred years of psychotherapy and the world’s getting worse. His message had become reactionary: therapy was making us weak, we needed to be tougher. These problems have existed since the Bronze Age, and Hillman’s delusion that he could fix them reveals the messianic inflation that had taken hold. He wasn’t the messiah, being right being brilliant doesn’t let you change the world. Even seeing the future doesn’t. Effective action does.

Tacey recalls Hillman’s jealousy toward his more commercially successful students, his desperate desire for financial security, his inability to translate his ideas into accessible form. The man who wanted to revolutionize psychology ended up as what Tacey calls someone “off with the fairies,” promoting dangerous ideas like the necessity of war while sitting safely in his armchair, never signing up for any actual conflict himself.

The Lessons of Hillman: Why Structure Matters

Hillman’s career stands as a cautionary tale about what happens when brilliant intellect operates without psychological grounding. His rejection of the ego-Self axis didn’t eliminate his ego; it just made it unconscious, where it inflated to grandiose proportions. His embrace of multiplicity without integration didn’t create psychological freedom; it created theoretical chaos that couldn’t translate into practical application.

The Jungian fundamentalists that Hillman railed against certainly needed challenging. Rigid orthodoxy stifles psychological life, and Hillman was right to point out the dangers of systematic thinking that loses touch with living images. But his solution of abandoning all systematic thinking, rejecting the Self, dissolving into archetypal multiplicity, was worse than the problem he was trying to solve.

What Hillman never understood, or couldn’t accept, was that the ego-Self axis isn’t a monotheistic tyranny but a necessary psychological structure that allows us to engage archetypal reality without being overwhelmed by it. The Self isn’t a rigid unity but a dynamic wholeness that contains and relates multiplicities. Development isn’t a linear prison but a spiral process that includes regression in service of progression.

The Tragedy of the Brilliant Rebel

James Hillman had what Tacey calls “a huge life” and made significant contributions to psychological thinking. His critiques of psychological orthodoxy, his emphasis on imagination and image, his passionate advocacy for soul remain valuable. But his inability to provide a workable alternative to what he criticized, his rejection of necessary psychological structures, and his eventual recognition that he couldn’t actually practice what he preached reveal the limitations of rebellion without reconstruction.

In the end, Hillman’s own career demonstrated why Jung’s structural insights matter. Without the ego-Self axis, even the most brilliant mind becomes subject to archetypal possession. Without an organizing principle, even the richest psychological insights dissolve into unusable fragments. And without the hard work of integration, the soul’s journey becomes an endless wandering in the wilderness rather than a transformative passage toward wholeness.

Perhaps Hillman’s greatest inadvertent contribution was to serve as living proof of why we need exactly those psychological structures he spent his career trying to demolish. His messianic tendencies, his inability to build rather than destroy, his appearance on right-wing talk radio toward the end of his life, and his final reconciliation with Jung all point to the same conclusion: the ego-Self axis isn’t optional equipment in psychological work. It’s the fundamental structure that allows us to engage the depths without drowning in them.

As David Tacey wisely observed, by throwing out the ego-Self axis, Hillman lost the very framework that could distinguish individuation from inflation, legitimate soul-making from regression to what Erich Neumann called “ouroboric incest.” The man who wanted to free the soul ended up demonstrating precisely why it needs some guiding structure to flourish. Perhaps he proved the point that “We are lived by forces that we pretend to understand”, the Auden quote he loved. By 1939, Auden was wrestling with how to reconcile human freedom with the hidden determinisms of psyche and history. One of the works that Auden wrote right before that quote was a volume that Hillman might have learned something from.

The point of The Orators is to dramatize a generation’s struggle with authority, masculinity, and the collapse of old moral and political structures. Auden wrote it between the world wars, when fascism, communism, and psychoanalysis were all competing to fill the vacuum left by traditional religion. The work explores how modern man, stripped of faith, seeks new myths of order or heroism—and how those myths can become dangerous if they harden into ideology.

Hillmans work is interesting, not because it represents a grand trajectory like Jungs, but it was a kind of in between of understanding. A yelling into a vacuum, but a profoundly interesting one.

0 Comments