Who was Emma Jung?

Emma Jung (1882-1955) was a Swiss psychoanalyst and author who made significant contributions to the field of analytical psychology. Though often overshadowed by her famous husband, Carl Gustav Jung, Emma was a formidable intellectual in her own right, developing key concepts that continue to influence Jungian theory and practice today. Her work on the anima and animus archetypes, in particular, has had a lasting impact on our understanding of the psyche and the process of individuation.

This essay explores Emma Jung’s life and work, situating her contributions within the broader context of depth psychology. It examines her key ideas, their significance for Jungian theory, and their continuing relevance for contemporary psychology. Finally, it offers a retrospective on Emma Jung’s legacy, assessing which of her ideas have stood the test of time and how her work compares to that of other figures in the field.

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- Emma Jung was a pioneering figure in analytical psychology, developing key concepts independently of her husband Carl Jung.

- Her work on the anima and animus archetypes significantly expanded our understanding of the contrasexual aspects of the psyche.

- Emma Jung’s exploration of the Grail legend provided valuable insights into the symbolic representation of psychological processes in myth and literature.

- Her approach to psychology emphasized the importance of balancing masculine and feminine principles within the psyche.

- Emma Jung’s work on active imagination and dream analysis contributed to the development of important therapeutic techniques in Jungian psychology.

- Her collaborative relationship with Carl Jung, while complex, was intellectually fruitful and influential in shaping both of their ideas.

- Emma Jung’s writings on marriage and relationships offered a depth psychological perspective on interpersonal dynamics.

- Her emphasis on the spiritual dimensions of psychological development aligned with the transpersonal aspects of Jungian psychology.

- Emma Jung’s work has been influential in feminist psychology, offering a nuanced view of gender and psyche.

- Her legacy continues to inspire contemporary Jungian analysts and scholars, particularly in the areas of feminine psychology and the integration of opposites.

Early Life and Collaboration with Carl Jung

A Complex Partnership: Emma and Carl Jung

Emma Jung’s relationship with Carl Jung was multifaceted and, at times, fraught with challenges. Their partnership was not only a marriage but also an intellectual collaboration that significantly influenced the development of analytical psychology. However, this intertwining of personal and professional lives often led to tension and difficulties.

Early Years and Collaboration:

In the early years of their marriage, Emma was not just a supportive wife but an active participant in Carl’s intellectual pursuits. She attended his lectures, discussed cases with him, and provided valuable insights that helped shape his theories. Emma’s keen intellect and psychological intuition made her an ideal partner for Carl as he developed his ideas on the unconscious, archetypes, and the process of individuation.

Emma played a crucial role in the famous “Wednesday Psychological Society” meetings at the Burghölzli Clinic, where she contributed to discussions and helped refine emerging concepts in analytical psychology. Her presence and input were instrumental in creating an environment of intellectual ferment that fostered the growth of Jungian psychology.

Challenges and Infidelity:

The Jung’s marriage faced significant strain when Carl became involved with Toni Wolff, one of his patients who later became his research assistant and mistress. This relationship, which lasted for decades, deeply wounded Emma and created ongoing tension in their marriage. Despite the pain this caused her, Emma made the difficult decision to remain in the marriage and even to accept Toni’s presence in their lives to some degree.

This situation led to a complex triangular relationship that, while personally challenging, also contributed to the development of Jung’s theories on the anima and the importance of integrating different aspects of the personality. Emma’s ability to contain this difficult situation and her willingness to engage with it psychologically became, in itself, a kind of lived experiment in Jungian concepts.

Separate but Interconnected Work:

As Carl’s theories gained prominence and his professional obligations increased, Emma began to develop her own independent work in analytical psychology. While she continued to support and collaborate with Carl, she also pursued her own areas of interest, particularly in her work on the animus archetype and her study of the Grail legend.

Emma’s explorations of the animus (the male aspect of the female psyche) complemented Carl’s work on the anima (the female aspect of the male psyche). Her insights into the ways the animus manifests in women’s psychology added depth and nuance to the overall Jungian understanding of the contrasexual archetypes.

The Grail Legend project, which Emma worked on for many years, was another area where her independent work intersected with the broader Jungian project. Her analysis of this medieval myth from a psychological perspective contributed to the Jungian approach to mythological and symbolic material.

Maintaining Individuality:

Despite the challenges in their personal relationship and the potential for being overshadowed by her famous husband, Emma managed to maintain her own identity and make significant contributions to analytical psychology. She gave lectures, wrote papers, and worked with her own analysands, establishing herself as a respected figure in the Jungian community in her own right.

Emma’s ability to balance her role as Carl’s wife and collaborator with her own independent work demonstrated in practice the Jungian ideal of individuation – the process of becoming one’s true self. Her journey exemplified the challenges and rewards of maintaining one’s individuality within the context of a powerful relationship.

Legacy of Their Partnership:

The complex partnership between Emma and Carl Jung left a lasting imprint on analytical psychology. Their collaboration, both in its harmonious and challenging aspects, contributed to a richer, more nuanced understanding of the human psyche. Emma’s ability to engage with Carl’s infidelity from a psychological perspective, painful as it was, provided lived insight into the integration of the shadow and the importance of holding tension between opposites.

Moreover, Emma’s independent work, particularly on the animus and the Grail legend, complemented and expanded Carl’s theories, contributing to a more comprehensive Jungian psychology. Her ability to maintain her own voice and perspective, even while deeply involved in Carl’s work, set an important precedent for women in the field of depth psychology.

In retrospect, the Jung’s marriage and intellectual partnership, with all its complexities and challenges, can be seen as a crucible in which many key Jungian concepts were not just theorized but lived. Their relationship demonstrated both the difficulties and the potential for growth inherent in the process of individuation and the integration of the personality.

Emma Jung’s ability to navigate this complex relationship while making her own unique contributions to analytical psychology is a testament to her strength, intelligence, and psychological insight. Her legacy serves as an inspiration for those seeking to balance personal relationships with individual development and professional achievement in the field of depth psychology.

Emma Jung’s Therapeutic Work

In addition to her theoretical contributions, Emma Jung was also an active therapist who worked with many patients over the course of her career. Her approach to therapy was deeply informed by her understanding of Jungian psychology and her own unique insights into the human psyche.

As a therapist, Emma Jung emphasized the importance of the therapeutic relationship itself as a vehicle for transformation. She saw the therapist-patient dynamic as a kind of alchemical vessel in which both parties could be transformed through their engagement with the unconscious.

Emma was known for her empathetic and intuitive style as a therapist. She had a keen ability to sense what was not being said directly and to help her patients give voice to their unspoken feelings and experiences. At the same time, she was not afraid to confront her patients when necessary, challenging them to face their shadows and to take responsibility for their own growth.

One of the unique aspects of Emma Jung’s therapeutic work was her willingness to draw on a wide range of symbolic and creative techniques. She often incorporated active imagination, dream analysis, and work with fairy tales and myths into her sessions, believing that these methods could help patients access deeper layers of the psyche.

Emma also had a particular interest in working with women and exploring the unique challenges and opportunities of feminine psychology. She saw her work with female patients as an opportunity to help them develop a stronger sense of their own identity and to find ways of expressing their creativity and spirituality in a patriarchal society.

The Cultural Context of Emma Jung’s Work

To fully appreciate Emma Jung’s contributions to analytical psychology, it is important to situate her work within the broader cultural and historical context of her time. As a woman working in the early 20th century, Emma faced significant barriers and challenges in pursuing her intellectual and professional ambitions.

The field of psychology was still in its infancy during Emma’s lifetime, and women were largely excluded from positions of authority and influence. Despite her obvious intelligence and capabilities, Emma was often overshadowed by her more famous husband and had to struggle to have her own ideas taken seriously.

At the same time, the early 20th century was a period of significant cultural upheaval and transformation. The traditional roles and expectations for women were beginning to shift, and there was a growing interest in exploring alternative models of gender and sexuality.

In many ways, Emma Jung’s work can be seen as a reflection of and response to these broader cultural currents. Her emphasis on the importance of integrating masculine and feminine principles within the psyche, for example, resonated with the emerging feminist consciousness of her time.

Similarly, Emma’s interest in mythology, fairy tales, and other forms of symbolic expression can be understood as part of a wider cultural fascination with the power of the imagination and the unconscious. Movements like Surrealism and Dada, which emerged during Emma’s lifetime, sought to tap into the creative potential of the psyche and to challenge conventional ways of perceiving reality.

Emma Jung’s work, then, was not simply a product of her own unique genius, but also a reflection of the complex cultural and historical forces that shaped her time. By situating her contributions within this broader context, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the ways in which her ideas both reflected and challenged the dominant assumptions of her era.

The Anima and Animus

Emma Jung’s most notable contribution to analytical psychology was her work on the anima and animus archetypes. While Carl Jung had initially conceptualized these as contrasexual aspects of the psyche – the feminine in men (anima) and the masculine in women (animus) – Emma developed a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of these archetypes.

In her view, the anima and animus were not simply opposite-sex components of the psyche, but complex, multifaceted archetypes that played a crucial role in psychological development and relationships. Emma Jung saw these archetypes as bridges between the conscious and unconscious mind, mediating between the individual ego and the collective unconscious.

Emma’s work on the animus, in particular, was groundbreaking. She identified four stages of animus development in women:

- The physical/power stage, represented by male figures of physical prowess.

- The romantic/action stage, embodied by heroic or adventurous male figures.

- The verbal/intellectual stage, characterized by articulate, intelligent male figures.

- The spiritual/wisdom stage, represented by wise, spiritual male figures.

This developmental model provided a framework for understanding how women’s relationship to masculine energy evolves over time, influencing their sense of self, their relationships, and their engagement with the world.

Emma Jung also emphasized that the goal of psychological development was not to eliminate or suppress these contrasexual aspects, but to integrate them consciously into one’s personality. This process of integration, she argued, was essential for achieving psychological wholeness and for developing mature, fulfilling relationships.

The Grail Legend

Another significant contribution of Emma Jung was her in-depth study of the Grail legend. In collaboration with Marie-Louise von Franz, she authored “The Grail Legend,” a comprehensive analysis of this medieval myth from a psychological perspective.

Emma Jung saw the Grail legend as a symbolic representation of the individuation process – the journey towards psychological wholeness. She interpreted the various characters and events of the legend as archetypes and psychological dynamics, offering insights into the challenges and transformations involved in personal growth.

For example, she saw the Fisher King, wounded and unable to heal, as a symbol of the psyche stuck in a state of unconsciousness or neurosis. The questing knight represented the ego’s journey towards consciousness and healing. The Grail itself symbolized wholeness and the Self – the ultimate goal of individuation.

Through this work, Emma Jung demonstrated the value of analyzing myths and legends as expressions of collective psychological processes. Her approach helped to bridge the gap between analytical psychology and literary studies, influencing later work in the field of mythological studies.

Marriage and Relationships

Emma Jung’s personal experience of marriage to a complex and often difficult man like Carl Jung informed her understanding of relationships from a depth psychological perspective. She wrote and lectured on the topic of marriage, offering insights into the psychological dynamics of intimate partnerships.

For Emma, marriage was not just a social institution but a vessel for psychological growth and transformation. She saw the marital relationship as a crucible in which both partners could confront their projections, work through their complexes, and develop a more integrated sense of self.

Emma Jung emphasized the importance of maintaining one’s individuality within the context of a committed relationship. She warned against the dangers of excessive merging or codependence, arguing that true intimacy required each partner to develop their own unique potential.

Her work on marriage and relationships was particularly influential in developing the concept of the “container” in analytical psychology – the idea that certain relationships and settings can provide a safe space for psychological work and transformation to occur.

Active Imagination and Dream Analysis

While Carl Jung is often credited with developing the technique of active imagination, Emma Jung also made significant contributions to this area. She used and refined the method in her own work with patients, emphasizing its value as a tool for engaging with the unconscious and integrating archetypal content.

Emma Jung saw active imagination as a way of bridging the gap between conscious and unconscious, allowing individuals to engage in dialogue with various aspects of their psyche. She believed that this process could lead to greater self-understanding and facilitate the integration of previously unconscious material.

In addition to active imagination, Emma Jung was also skilled in dream analysis. She emphasized the importance of understanding dreams not just as expressions of personal unconscious material, but as communications from the collective unconscious. Her approach to dream interpretation was nuanced and contextual, taking into account the dreamer’s personal associations as well as universal symbolic meanings.

Spiritual Dimensions of Psychology

Like her husband, Emma Jung was deeply interested in the spiritual dimensions of psychological development. She saw the process of individuation as inherently spiritual, involving not just personal growth but a connection to transpersonal or cosmic realities.

Emma Jung’s work often touched on themes of meaning, purpose, and transcendence. She believed that true psychological health involved not just the absence of symptoms, but a sense of connection to something greater than oneself. This perspective aligned with the transpersonal aspects of Jungian psychology and anticipated later developments in the field of transpersonal psychology.

Her exploration of spiritual themes was not confined to traditional religious contexts. Emma Jung was interested in a wide range of spiritual and esoteric traditions, including alchemy, Gnosticism, and Eastern philosophies. She saw these various traditions as different symbolic languages for describing universal psychological processes.

Feminist Perspectives

While Emma Jung did not identify explicitly as a feminist, her work has been influential in feminist psychology. Her nuanced understanding of the animus archetype, in particular, offered a more complex view of feminine psychology than was common at the time.

Emma Jung’s emphasis on the importance of women developing their own intellectual and spiritual capacities was progressive for her era. She encouraged women to engage with their animus energy not just in relation to men, but as a source of personal power and creativity.

At the same time, Emma Jung’s work has been criticized by some feminist scholars for its adherence to binary gender categories and its potential reinforcement of gender stereotypes. However, many contemporary Jungian feminists have found ways to build on Emma Jung’s insights while adapting them to more fluid and inclusive understandings of gender.

Legacy and Influence

Emma Jung’s contributions to analytical psychology have had a lasting impact on the field. Her work on the anima and animus continues to inform Jungian approaches to gender and relationships. Her analysis of the Grail legend remains a seminal text in the psychological interpretation of myth.

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in Emma Jung’s work, with scholars and analysts recognizing her unique contributions to the field. Her emphasis on the integration of masculine and feminine principles within the psyche resonates with contemporary interest in non-binary and holistic approaches to gender and identity.

Emma Jung’s collaborative relationship with Carl Jung has also been the subject of increased attention. While their personal relationship was often strained, their intellectual partnership was crucial to the development of analytical psychology. Emma’s role as both supporter and critic of Carl’s work helped to shape and refine many key concepts in Jungian theory.

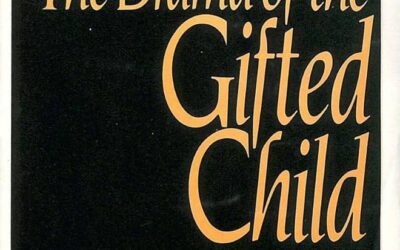

Critique and Retrospective

As with any influential thinker, Emma Jung’s work has been subject to critique and revision over time. Some of the limitations and biases of her approach include:

Binary gender assumptions:

Emma Jung’s work on anima and animus relies heavily on a binary understanding of gender, which may not fully account for the diversity of gender identities and expressions.

Cultural specificity:

Like much of early psychoanalytic theory, Emma Jung’s ideas were developed primarily in a Western, European context and may not be universally applicable.

Essentialism:

Some critics argue that Emma Jung’s approach to feminine psychology risks essentializing women’s experiences and reinforcing gender stereotypes.

Lack of empirical evidence:

As with much of depth psychology, Emma Jung’s theories are based primarily on clinical observation and symbolic interpretation rather than empirical research.

Despite these limitations, Emma Jung’s work continues to offer valuable insights into the nature of the psyche and the process of individuation. Her emphasis on the integration of opposites, the importance of symbolic thinking, and the spiritual dimensions of psychological development remain relevant to contemporary psychology.

As we navigate the complexities of gender, identity, and relationships in the 21st century, Emma Jung’s nuanced exploration of the interplay between masculine and feminine principles within the psyche offers a rich resource for reflection and analysis. Her work reminds us of the importance of engaging with the full range of our psychic potentials, regardless of our gender identity or expression.

Moreover, Emma Jung’s collaborative approach to intellectual work, her integration of psychological and spiritual perspectives, and her emphasis on the transformative power of symbolic thinking continue to inspire scholars and practitioners in the field of depth psychology.

Emma Jung’s contributions to analytical psychology, while often overshadowed by those of her famous husband, represent a significant and unique body of work. Her explorations of the anima and animus archetypes, her analysis of myth and symbol, and her insights into the nature of relationships have enriched our understanding of the human psyche and the process of individuation.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Timeline of Emma Jung’s Life and Work

1882 – March 30: Emma Rauschenbach is born in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, to a wealthy industrialist family.

1896 – Emma meets Carl Jung for the first time when he visits her father’s house. She is 14, and he is 21.

1902 – Emma begins a correspondence with Carl Jung.

1903 – February 14: Emma marries Carl Jung at the age of 20. They move to Zürich where Carl works at Burghölzli psychiatric hospital.

1904 – December: Birth of their first child, Agathe.

1906 – October: Birth of their second child, Gret.

1908 – November: Birth of their third child, Franz.

1909 – Emma accompanies Carl on his trip to the United States, where he meets Sigmund Freud for the first time.

1910 – August: Birth of their fourth child, Marianne.

1911 – Emma begins to study psychology more seriously, attending lectures and seminars.

1914 – April: Birth of their fifth and last child, Helene.

1920s – Emma starts developing her own psychological theories, particularly focusing on the animus concept.

1925 – Emma becomes an associate member of the Psychological Club in Zürich.

1931 – Begins writing her book on the Grail Legend.

1934 – Gives her first public lecture at the Psychological Club in Zürich on “The Animus Problem in Modern Woman.”

1936 – Publishes her paper “On the Nature of the Animus” in the Zentralblatt für Psychotherapie.

1940s – Continues to develop and refine her ideas on anima and animus, giving lectures and working with patients.

1941 – Publishes “The Problem of the Feminine in Fairytales” in the journal Spring.

1944 – Gives a seminar on “The Animus in the Fairy Tale” at the Psychological Club.

1948 – Presents a paper on “The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales” at the International Congress for Psychotherapy in Zürich.

1950 – Continues work on her Grail Legend manuscript despite declining health.

1953 – Collaborates with Marie-Louise von Franz on completing the Grail Legend book.

1955 – November 27: Emma Jung passes away in Küsnacht, Zürich, Switzerland, at the age of 73.

1957 – Her unfinished manuscript on the Grail Legend, completed by Marie-Louise von Franz, is posthumously published as “The Grail Legend.”

1985 – A collection of her writings on animus and anima is posthumously published as “Animus and Anima.”

Bibliography:

Jung, Emma. Animus and Anima. Spring Publications, 1985.

Jung, Emma, and von Franz, Marie-Louise. The Grail Legend. Princeton University Press, 1998.

Bair, Deirdre. Jung: A Biography. Little, Brown and Company, 2003.

Kast, Verena. Father-Daughter, Mother-Son: Freeing Ourselves from the Complexes that Bind Us. Element Books, 1997.

Wehr, Gerhard. Jung: A Biography. Shambhala, 1987.

Young-Eisendrath, Polly. Gender and Desire: Uncursing Pandora. Texas A&M University Press, 1997.

Rowland, Susan. Jung: A Feminist Revision. Polity Press, 2002.

Stein, Murray. Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court, 1998.

Samuels, Andrew. Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge, 1985.

Douglas, Claire. The Woman in the Mirror: Analytical Psychology and the Feminine. Sigo Press, 1990.

Further Reading:

Jung, Emma. Animus and Anima. Spring Publications, 1985. Jung, Emma, and von Franz, Marie-Louise. The Grail Legend. Princeton University Press, 1998. Bair, Deirdre. Jung: A Biography. Little, Brown and Company, 2003. Kast, Verena. Father-Daughter, Mother-Son: Freeing Ourselves from the Complexes that Bind Us. Element Books, 1997. Wehr, Gerhard. Jung: A Biography. Shambhala, 1987. Young-Eisendrath, Polly. Gender and Desire: Uncursing Pandora. Texas A&M University Press, 1997. Rowland, Susan. Jung: A Feminist Revision. Polity Press, 2002. Stein, Murray. Jung’s Map of the Soul: An Introduction. Open Court, 1998. Samuels, Andrew. Jung and the Post-Jungians. Routledge, 1985. Douglas, Claire. The Woman in the Mirror: Analytical Psychology and the Feminine. Sigo Press, 1990. von Franz, Marie-Louise. The Feminine in Fairy Tales. Shambhala, 1993. Hillman, James. Anima: An Anatomy of a Personified Notion. Spring Publications, 1985. Singer, June. Boundaries of the Soul: The Practice of Jung’s Psychology. Anchor, 1994. Zabriskie, Beverly. “Jung and Pauli: A Subtle Asymmetry.” Journal of Analytical Psychology, vol. 40, no. 4, 1995, pp. 531-553. Woodman, Marion. The Ravaged Bridegroom: Masculinity in Women. Inner City Books, 1990.

0 Comments