Identity, Development, and the Life Cycle

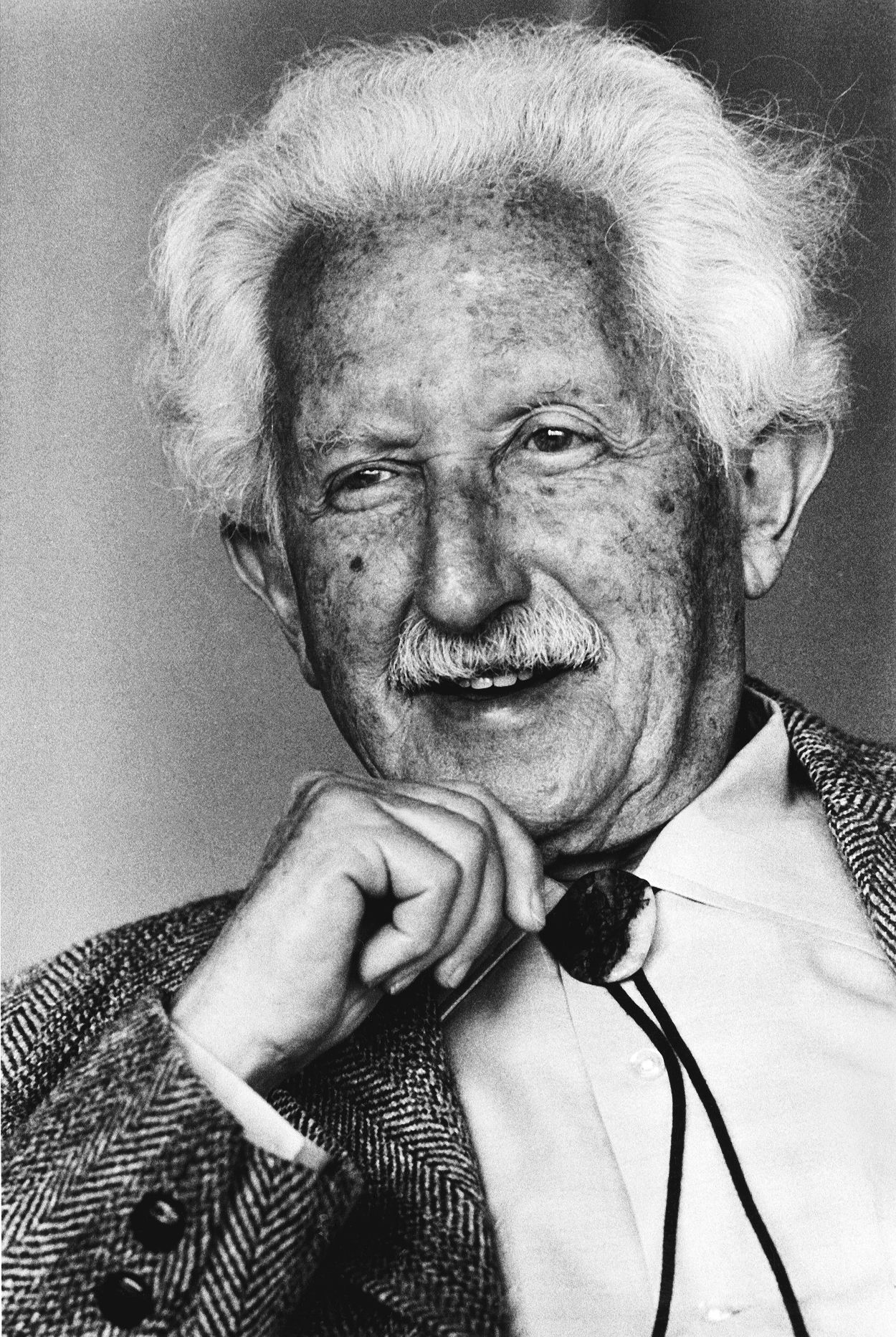

Who was Erik Erikson?

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) emerged as one of the most influential voices in 20th-century psychology, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of human development and identity formation. His journey from an art student in Vienna to a groundbreaking psychoanalyst in America mirrors the very identity exploration he would later theorize, demonstrating the profound interplay between personal experience and theoretical insight.

Born in Frankfurt, Germany, to Danish parents, Erikson’s early life was marked by the kind of identity questions that would later inform his theoretical work. As a tall, blonde, Nordic-looking youth in a Jewish school, he experienced firsthand the complexity of identity formation and the challenge of finding one’s place in the world. This personal history would later inform his sensitive treatment of identity development and his understanding of the crucial role that social and cultural contexts play in human development.

Erikson’s path to psychology was unconventional. After completing his schooling, he chose to become an artist, wandering through Europe as a bohemian painter. This period of exploration led him to Vienna, where he was invited to teach art at a small school run by Dorothy Burlingham, a friend of Anna Freud. This connection would prove pivotal, leading Erikson into the emerging field of child psychoanalysis and eventually to his groundbreaking contributions to developmental theory.

What distinguished Erikson from his psychoanalytic contemporaries was his ability to transcend the biological determinism of classical Freudian theory while retaining its valuable insights into human development. Where Freud focused primarily on the psychosexual dynamics of early childhood, Erikson expanded the scope of developmental theory to encompass the entire human lifespan. His psychosocial theory of development, articulated through eight distinct stages, revolutionized our understanding of how individuals grow and change throughout their lives.

Erikson’s theoretical innovations were matched by methodological creativity. He pioneered the integration of direct observation of children with psychoanalytic insight, anthropological field studies, and historical analysis. This multidisciplinary approach allowed him to demonstrate how individual development is inextricably linked to social and cultural contexts, leading to his groundbreaking work in psychohistory through biographical studies of figures like Martin Luther and Mahatma Gandhi.

The concept of identity, perhaps Erikson’s most significant theoretical contribution, emerged from this rich synthesis of personal experience, clinical observation, and cross-cultural study. His exploration of identity formation and the “identity crisis” provided a framework for understanding the challenges of personal development that remains relevant in our contemporary world of rapid social change and cultural transformation.

-

Theoretical Foundations: Beyond Freudian Orthodoxy

Erikson’s theoretical innovations represented both a continuation and a transcendence of Freudian psychoanalysis. While maintaining the basic psychoanalytic emphasis on unconscious processes and early experience, Erikson significantly expanded the scope of developmental theory in several crucial ways.

First, he extended the timeline of development beyond childhood and adolescence to encompass the entire human lifespan. This revolutionary step acknowledged that psychological growth and change continue throughout life, with each stage presenting its own challenges and opportunities for development.

Second, Erikson shifted the focus from psychosexual to psychosocial development. While not denying the importance of biological drives, he emphasized the crucial role of social relationships and cultural context in shaping human development. This shift allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of how individuals interact with their environment and develop their sense of self.

Third, Erikson introduced the concept of the epigenetic principle to developmental psychology. Borrowed from embryology, this principle suggests that development unfolds through a predetermined sequence of stages, each building upon the previous ones. This provided a framework for understanding both the universal aspects of human development and the unique ways in which individuals and cultures navigate these common challenges.

-

The Eight Stages of Psychosocial Development: A Life-Span Perspective

Erikson’s most enduring contribution to psychology lies in his articulation of eight distinct stages of psychosocial development. Each stage presents a fundamental crisis or conflict that must be negotiated, leading to either the development of a particular strength or the persistence of a corresponding vulnerability. This framework revolutionized our understanding of human development by extending it across the entire lifespan.

Trust versus Mistrust, the first stage spanning infancy, establishes the foundation for all subsequent development. Through consistent, nurturing care, infants develop what Erikson termed “basic trust” – a fundamental sense that the world is reliable and that their needs will be met. This basic trust becomes the cornerstone for healthy personality development, enabling the child to venture forth into the world with confidence. Conversely, inconsistent or neglectful care leads to basic mistrust, a pervasive sense of uncertainty and insecurity that can color all future relationships.

The second stage, Autonomy versus Shame and Doubt, coincides with early toddlerhood as children begin to assert their independence. Success at this stage depends on caregivers’ ability to support the child’s growing autonomy while maintaining appropriate boundaries. Erikson noted that cultures vary significantly in how they handle this balance, reflecting different values regarding independence and interdependence.

Initiative versus Guilt, the third stage, emerges during the preschool years as children’s increasing physical and cognitive capabilities allow them to undertake more complex activities. This stage sees the emergence of conscience and the capacity for self-directed activity. Erikson emphasized that healthy development requires finding a balance between spontaneous initiative and moral restraint.

The fourth stage, Industry versus Inferiority, corresponds to the elementary school years. Here, children develop competence through meaningful work and achievement. Erikson was particularly attuned to how different cultures structure this period, noting that traditional societies often integrate children into adult work activities, while modern societies separate children’s “work” (schooling) from adult labor.

Identity versus Role Confusion, the fifth stage and perhaps Erikson’s most famous contribution, marks the adolescent period. This crucial phase involves integrating various aspects of one’s experience – including physical changes, cognitive development, and social expectations – into a coherent sense of self. Erikson’s concept of the “identity crisis” emerged from his understanding of this stage’s challenges.

The sixth stage, Intimacy versus Isolation, characterizes young adulthood. Having established a relatively stable identity, individuals face the challenge of forming deep, committed relationships without losing their sense of self. Erikson viewed this stage as crucial for both personal fulfillment and social continuity.

Generativity versus Stagnation, the seventh stage, emerges in middle adulthood. Here, individuals confront questions of legacy and contribution to future generations. This stage reflects Erikson’s understanding that healthy development involves transcending pure self-interest to care for the broader human community.

The final stage, Ego Integrity versus Despair, involves coming to terms with one’s life as lived. Success at this stage leads to wisdom – the ability to accept life’s limitations while maintaining its essential dignity and meaning. This understanding of late-life development was groundbreaking, challenging prevalent views of aging as mere decline.

-

Identity Formation: The Core of Human Development

Erikson’s theory of identity formation represents perhaps his most significant theoretical innovation. Unlike previous theorists who viewed identity primarily in terms of individual personality traits, Erikson understood identity as fundamentally psychosocial – emerging from the interaction between individual capacities and social recognition.

Identity formation, in Erikson’s view, involves both conscious and unconscious processes. The conscious aspect includes the individual’s deliberate exploration of different roles, values, and possible futures. The unconscious dimension involves the integration of early identifications, cultural imperatives, and biological predispositions into a coherent whole.

Erikson introduced the concept of the “identity crisis” not as a catastrophic breakdown but as a necessary period of intense exploration and commitment. This normative crisis enables young people to forge an authentic identity by questioning inherited assumptions and exploring alternative possibilities. The resolution of this crisis involves achieving what Erikson termed “fidelity” – the ability to maintain commitments despite inevitable contradictions and confusions.

The process of identity formation occurs through what Erikson called “psychosocial moratorium” – a socially sanctioned period of exploration free from adult responsibilities. He noted that different societies structure this moratorium differently, reflecting varying cultural values and social needs. Modern societies, with their complex division of labor and rapid technological change, tend to require longer moratoriums than traditional societies.

-

Psychohistory: A New Method of Inquiry

Erikson pioneered the field of psychohistory, developing a sophisticated methodology for understanding the interplay between individual development and historical circumstances. His biographical studies of Martin Luther and Mahatma Gandhi demonstrated how personal identity formation intersects with broader historical movements and cultural transformation.

In “Young Man Luther,” Erikson traced how Luther’s personal identity crisis became intertwined with the religious and social upheavals of the Reformation. He showed how Luther’s struggle with authority – both paternal and ecclesiastical – reflected and catalyzed broader cultural tensions. This analysis revealed how individual psychological development can both shape and be shaped by historical circumstances.

Similarly, in “Gandhi’s Truth,” Erikson explored how Gandhi’s development of nonviolent resistance emerged from the intersection of personal experience, cultural tradition, and historical necessity. He demonstrated how Gandhi’s identity formation involved synthesizing Indian spiritual traditions with Western political concepts, creating a new form of moral and political action.

These psychohistorical studies illustrated Erikson’s broader theoretical point that identity formation always occurs within specific historical and cultural contexts. The individual’s struggle for authentic selfhood necessarily engages with the particular challenges and possibilities of their time and place.

-

Clinical Applications: The Therapeutic Process

Erikson’s theoretical insights transformed clinical practice, offering a more comprehensive framework for understanding psychological development and therapeutic change. His approach emphasized the importance of considering the patient’s current developmental stage and cultural context, rather than focusing exclusively on early childhood experiences.

In clinical work, Erikson advocated what he called “triple bookkeeping” – attending simultaneously to biological, psychological, and social dimensions of experience. This integrated approach helped therapists understand how physical development, individual psychology, and social context interact to shape both problems and possibilities for growth.

His concept of the identity crisis proved particularly valuable in work with adolescents and young adults. Rather than pathologizing their struggles with identity and purpose, Erikson’s framework helped clinicians recognize these as normal developmental challenges requiring support and understanding rather than medical intervention.

-

Social and Cultural Implications

Erikson’s theories had profound implications for education, social policy, and cultural understanding. His emphasis on the social context of development highlighted how institutional structures and cultural practices either support or hinder healthy psychological growth.

In education, his work suggested the importance of matching educational approaches to developmental stages. He emphasized that schools should provide not just academic instruction but opportunities for industry, identity exploration, and meaningful achievement. His insights continue to influence educational theory and practice, particularly in areas like social-emotional learning and adolescent education.

His understanding of identity formation has proved especially relevant to multicultural societies. Erikson recognized that forming a coherent identity becomes more complex when individuals must integrate different, sometimes conflicting cultural traditions. His work helps explain both the challenges and creative possibilities of cultural hybridity.

-

Contemporary Relevance: Digital Age Applications

Erikson’s theories maintain striking relevance in the digital age, offering insights into contemporary challenges of identity formation and social connection. His understanding of identity as both personal and social helps illuminate how digital technologies create new possibilities and challenges for self-development.

Social media platforms, for instance, can be understood as new arenas for identity exploration and social recognition. They offer unprecedented opportunities for role experimentation and community formation, while also presenting risks of premature identity foreclosure or fragmentation.

The concept of psychosocial moratorium takes on new meaning in an era where digital technologies both extend and complicate the period of identity exploration. Young people today must integrate online and offline experiences into a coherent sense of self, often navigating multiple digital contexts with different social expectations.

-

Critical Perspectives and Contemporary Developments

While Erikson’s theories have shown remarkable durability, contemporary scholars have both critiqued and extended his work. Feminist theorists have questioned the gender assumptions in his model, particularly his understanding of identity formation through separation and autonomy rather than connection and relationship.

Postmodern theorists have challenged his assumption of a unified, coherent identity, suggesting that contemporary life may require more fluid, multiple forms of selfhood. However, Erikson’s basic insight about the importance of finding some form of psychosocial synthesis remains relevant.

Cultural critics have noted that his model, while more culturally sensitive than many of his contemporaries, still reflects certain Western assumptions about individual development and autonomy. Contemporary scholars work to adapt his insights to diverse cultural contexts while maintaining his essential understanding of development as a psychosocial process.

-

Legacy and Future Directions

Erikson’s enduring influence stems from his ability to combine theoretical sophistication with practical relevance. His work continues to inform fields as diverse as education, mental health, social work, and organizational development.

His framework provides valuable tools for understanding contemporary challenges like extended adolescence, changing family structures, and technological transformation. His emphasis on the interaction between individual development and social change remains especially pertinent in an era of rapid cultural evolution and global interconnection.

Looking forward, Erikson’s theories suggest important questions about how human development may be changing in response to new social conditions. How do digital technologies affect identity formation? What new forms of generativity might emerge in an age of environmental crisis? How can societies support healthy development in an increasingly complex and interconnected world?

-

The Continuing Relevance of Erikson’s Vision

Erik Erikson’s theoretical contributions represent a watershed in our understanding of human development. By expanding psychological theory beyond childhood, emphasizing the role of social context, and illuminating the process of identity formation, he created a more comprehensive and humanistic vision of human growth.

His legacy reminds us that development is a lifelong process, shaped by both personal choices and social conditions. As we face contemporary challenges of identity, meaning, and community, Erikson’s framework continues to offer valuable tools for understanding and supporting human development across the life course.

In an age of rapid social change and global challenges, Erikson’s vision of human development as a psychosocial process remains more relevant than ever. His work invites us to consider how we can create conditions that support healthy development at all life stages, fostering the emergence of strong identities and meaningful lives in an increasingly complex world.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Primary Sources by Erik Erikson:

1. Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and Society. W. W. Norton & Company.

A foundational text introducing his eight stages of psychosocial development.

2. Erikson, E. H. (1958). Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History. W. W. Norton & Company.

Pioneering work in psychohistory examining Luther’s identity crisis.

3. Erikson, E. H. (1964). Insight and Responsibility. W. W. Norton & Company.

Collection of essays on ethical implications of psychoanalytic insight.

4. Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis. W. W. Norton & Company.

Detailed exploration of identity formation and the identity crisis concept.

5. Erikson, E. H. (1969). Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence. W. W. Norton & Company.

Pulitzer Prize-winning psychohistorical study of Gandhi’s development.

6. Erikson, E. H. (1974). Dimensions of a New Identity. W. W. Norton & Company.

Examination of identity in relation to contemporary social issues.

7. Erikson, E. H. (1982). The Life Cycle Completed: A Review. W. W. Norton & Company.

Final synthesis of his life-cycle theory.

8. Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1997). The Life Cycle Completed: Extended Version. W. W. Norton & Company.

Updated version including new material on the ninth stage of development.

Secondary Sources and Critical Works:

Theoretical Foundations:

1. Friedman, L. J. (1999). Identity’s Architect: A Biography of Erik H. Erikson. Scribner.

The definitive biography, providing comprehensive context for his theories.

2. Hoare, C. H. (2002). Erikson on Development in Adulthood: New Insights from the Unpublished Papers. Oxford University Press.

Analysis of Erikson’s later theoretical developments.

3. Welchman, K. (2000). Erik Erikson: His Life, Work, and Significance. Open University Press.

Accessible overview of Erikson’s contributions.

Identity Development:

4. Kroger, J. (2007). Identity Development: Adolescence Through Adulthood (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Detailed examination of identity formation across the lifespan.

5. Marcia, J. E., Waterman, A. S., Matteson, D. R., Archer, S. L., & Orlofsky, J. L. (1993). Ego Identity: A Handbook for Psychosocial Research. Springer-Verlag.

Comprehensive research handbook building on Erikson’s identity concept.

6. Schwartz, S. J., Luyckx, K., & Vignoles, V. L. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. Springer.

Contemporary perspectives on identity development.

Clinical Applications:

7. Douvan, E. (1997). Erik Erikson: Critical Times, Critical Theory. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 28(1), 15-21.

Analysis of clinical applications of Erikson’s theories.

8. Monte, C. F., & Sollod, R. N. (2003). Beneath the Mask: An Introduction to Theories of Personality (7th ed.). Wiley.

Places Erikson’s theories in broader clinical context.

Cultural and Social Perspectives:

9. Capps, D. (2004). The Decades of Life: A Guide to Human Development. Westminster John Knox Press.

Religious and cultural implications of Erikson’s stage theory.

10. Slugoski, B. R., & Ginsburg, G. P. (1989). Ego Identity and Explanatory Speech. In J. Shotter & K. J. Gergen (Eds.), Texts of Identity (pp. 36-55). Sage Publications.

Sociological perspective on identity formation.

Contemporary Applications:

11. Côté, J. E. (2009). Youth-Identity Studies: History, Controversies, and Future Directions. Journal of Youth Studies, 12(1), 1-16.

Contemporary applications of identity theory.

12. Whitbourne, S. K., & Weinstock, C. S. (1979). Adult Development: The Differentiation of Experience. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Application to adult development.

Research Methods and Assessment:

13. Waterman, A. S. (Ed.). (1985). Identity in Adolescence: Processes and Contents. Jossey-Bass.

Methodological approaches to studying identity.

14. Adams, G. R., Bennion, L. D., & Huh, K. (1989). Objective Measure of Ego Identity Status: A Reference Manual. Utah State University.

Assessment tools based on Erikson’s theory.

Further Reading for Specific Topics:

Adolescent Development:

15. Adams, G. R., & Berzonsky, M. D. (Eds.). (2003). Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence. Blackwell.

16. Kroger, J. (2004). Identity in Adolescence: The Balance between Self and Other. Routledge.

Adult Development:

17. Levinson, D. J. (1978). The Seasons of a Man’s Life. Knopf.

18. McAdams, D. P. (1993). The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self. Guilford Press.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives:

19. Gardiner, H. W., & Kosmitzki, C. (2010). Lives Across Cultures: Cross-Cultural Human Development (5th ed.). Pearson.

20. Jensen, L. A. (Ed.). (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Human Development and Culture. Oxford University Press.

Contemporary Identity Issues:

21. Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. Oxford University Press.

22. Zhao, S. (2005). The Digital Self: Through the Looking Glass of Telecopresent Others. Symbolic Interaction, 28(3), 387-405.

Journal Articles and Research Papers:

23. Grotevant, H. D. (1987). Toward a Process Model of Identity Formation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 2(3), 203-222.

24. Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The Identity Statuses: Origins, Meanings, and Interpretations. In S. J. Schwartz et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (pp. 31-53). Springer.

25. Syed, M., & McLean, K. C. (2016). Understanding Identity Integration: Theoretical, Methodological, and Applied Issues. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 109-118.

Online Resources and Digital Archives:

26. Erik Erikson Papers. Yale University Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Contains unpublished manuscripts and correspondence.

27. The Erik Erikson Center at Austen Riggs Center

Maintains archives and continues research in psychosocial development.

28. International Society for Research on Identity Development (ISRID)

Professional organization devoted to identity research.

Multimedia Resources:

29. Evans, R. I. (1969). Dialogue with Erik Erikson. Harper & Row.

Transcribed conversations with Erikson about his theories.

30. Identity and the Life Cycle: Selected Papers (Audio Recording). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Recorded lectures by Erikson.

0 Comments