Reckoning with the Spiritual and Mystical in Neurology

The Polyvagal Theory and Attachment

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory has revolutionized our understanding of the autonomic nervous system’s role in regulating emotional states and social engagement (Porges, 2011). According to this theory, the autonomic nervous system plays a crucial role in shaping our emotional experiences and attachment styles. In secure attachment, where caregivers are attuned and responsive, the ventral vagal complex promotes feelings of safety and connection, allowing for the healthy experience of emotional arcs, with emotions rising, peaking, and resolving in a regulated manner (Porges, 2011). The prefrontal cortex, associated with explicit memory, can process and make sense of these emotional experiences, while the subcortical regions, linked to implicit memory, store the felt sense of safety and resolution (Siegel, 2012).

However, in insecure attachment styles (avoidant, ambivalent, disorganized), the autonomic nervous system can become dysregulated due to inconsistent or threatening caregiving (Porges, 2011; Schore, 2001). This dysregulation can lead to enmeshment, avoidance, or ambivalence towards certain emotional arcs. For example, in avoidant attachment, the dorsal vagal complex may be overactive, leading to emotional suppression and disconnection (Porges, 2011). This can result in an avoidance of the entire emotional arc, as the implicit memory of the felt sense of danger or abandonment overrides the explicit memory of the actual event (Siegel, 2012).

Memory, Neurology, and the Emotional Arc

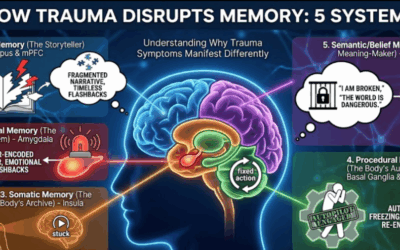

When traumatic experiences disrupt this integration, leading to dissociation and fragmentation, the individual may become stuck in incomplete emotional arcs, unable to fully process and resolve the distressing experiences.

The neuroscience of memory reconsolidation suggests that our sense of self is not a fixed, unitary entity, but rather an ongoing construction built from the synthesis of multiple memory networks (Siegel, 1999). Different types of memory, such as implicit (procedural and emotional) and explicit (semantic and episodic), are encoded in various parts of the brain, including the subcortical regions and the prefrontal cortex (Rothschild, 2000). For an emotional arc to be completed and integrated into a coherent self-narrative, these different memory systems must work together harmoniously.

However, trauma can cause a rupture in this integration process, leading to a fragmented sense of self and incomplete emotional arcs (van der Kolk, 2014). The individual may become stuck in a particular phase of the emotional arc, such as the rising intensity or the peak, unable to move towards resolution and integration. This can manifest as a paradoxical tension between different parts of the self, with some aspects of the psyche holding the traumatic experience and others dissociating from it (Bromberg, 1998).

The process of completing emotional arcs and reintegrating the self involves embracing these paradoxical tensions and allowing space for all aspects of the psyche to coexist (Jung, 1939). By acknowledging and accepting the seemingly contradictory parts of the self – the wounded and the resilient, the fearful and the courageous – the individual can begin to bridge the dissociative gaps and move towards a more coherent, flexible sense of identity (Siegel, 2010).

Edinger on the Interplay of Objective and Subjective

Selves Post-Jungian scholar and therapist Edward Edinger’s work in “Ego and Archetype” sheds light on the fundamental disagreement between two parts of the brain in solving problems, which may be at the root of the split between implicit and cognitive memory in traumatic ANS regulation (Edinger, 1972). Edinger posits that we have an inherently objective brain and an inherently subjective brain that often disagree, with one acting on subjective feeling and the other on objective fact. This dichotomy is evident in the best models of therapy, which aim to reconcile these conflicting realities. Trauma can exacerbate the fight between and over-identification with different parts of the brain.

Edinger’s conception of the self is a process, or Axis, between subjective feeling/subcortical brain and ego/objective brain. The authentic self is conceptualized as a process, not a destination, aligning with other experiential therapies such as IFS, DBT, and gestalt therapy. The self represents a synthesis and awareness between the two parts, with both subjective and objective minds brought into awareness without one mastering the other.

Recent anthropological and evolutionary biology research supports Edinger’s perspective, indicating that the evolution of the precuneus in the brain of Homo sapiens is linked to religious capacity (Rappaport & Corbally, 2018). The precuneus plays a significant role in reflective self-awareness, and with the evolution of consciousness and self-awareness, instinctual drives became parts of our collective unconscious (Neumann, 1954). The conflict between the needs of the ego in the relatively new prefrontal cortex and the instincts in the ancient subcortical brain causes the anxiety described by Edinger.

Research and Academia as Obstacles and Future Allies

The tension between objective and subjective, existential and mystical, is something that models of therapy often hold poorly or not at all. Most models validate mostly subjective or mostly objective experiences of the patient, depending on the personality type and biases of the founder of the model. This skews most models of psychotherapy towards pushing patients into living in only one half of their psyche, thus healing imperfectly.

Objective models run the risk of ignoring the roots of trauma in the (subjective) deep brain, while subjective models run the risk of making a patient’s feelings and emotional needs more important than accepting and reconciling with the demands of objective reality. To be whole and act effectively in the world, we must admit both emotional reality and existential reality as part of our experience.

Introducing more subjectivity, qualitative data, and intuitive understanding to psychotherapy is something that academia often resists. However, real science is bigger than purely empirical randomized controlled trials, and soft sciences do not fit perfectly into objective measurements. Some of the most important truths are metaphors that can only be grasped intuitively.

Introducing more subjectivity, qualitative data and intuitive conception and rationale to psychotherapy is something that academia resists. It is wonderful to have an empirical basis for reality where it is available but there are some psychic spaces that objectivity cannot go. There is an insecurity that some academics have that unless something is provable with a number then it isn’t real.

I would counter that anything composed of completely empirical variables is not psychology. I am not arguing for pseudoscience here or impulsive self important application of whim disguised as intuition. I am saying that real science is bigger than purely empirical randomized controlled trials and that soft sciences do not fit perfectly into objective measurements.

I do not believe that our humanity fits into objective numbers or that we should pull our humanity out of any discipline. Some things about phenomenology can only be captured in case studies and subjective impressions. Even some of the most important parts of psychology can only be gestured at this way and never fully quantified. Some of the most important truths are metaphors that can only be grasped intuitively. Most scientists, researchers and academics understand this perfectly well and apply it all the time.

Psychology is hopeless and corrupted in the hands of bureaucrats and accountants that cannot believe something unless an abacus or a father figure in a white coat tells them it is real. Real therapists have no burden of proof to these people that have taken over the profession to turn a dollar into a dollar ninety nine by removing all variables from psychology except behavior. “Behavioral health” is a despicable reductism employed as a cudgel to drive anyone capable out of mental healthcare. I do not practice “behavioral health”. I practice psychology.

Bibliography

Bromberg, P. M. (1998). Standing in the spaces: Essays on clinical process, trauma, and dissociation. Psychology Press.

Cozolino, L. (2017). The neuroscience of psychotherapy: Healing the social brain (3rd ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.

Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and archetype. Shambhala Publications.

Gould, S. J., & Lewontin, R. C. (1979). The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist programme. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, 205(1161), 581-598.

Herman, J. L. (1997). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence–from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Heijmans, B. T., Tobi, E. W., Stein, A. D., Putter, H., Blauw, G. J., Susser, E. S., … & Lumey, L. H. (2008). Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(44), 17046-17049.

Jung, C. G. (1939). The integration of the personality. Farrar & Rinehart.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 121-160). University of Chicago Press.

Montaigne, M. D. (1965). The complete essays of Montaigne. Stanford University Press. (Original work published 1580)

Nader, K. (2015). Reconsolidation and the dynamic nature of memory. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(10), a021782.

Neumann, E. (1954). The origins and history of consciousness. Princeton University Press.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rappaport, M. B., & Corbally, C. (2018). Evolution of religious capacity in the genus Homo: Trait complexity in action through compassion. Journal of Religion and Science, 53(1), 198-239.

Rothschild, B. (2000). The body remembers: The psychophysiology of trauma and trauma treatment. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rymaszewska, J., & Ramiah, A. (2016). Paradoxes of the self: Philosophical and psychological perspectives. Springer.

Schore, A. N. (2001). The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1-2), 201-269.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. Guilford Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. W. W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Tacey, D. (2022). Jung’s conflict with Freud and the birth of analytical psychology. Routledge.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

van Deurzen, E. (2009). Everyday mysteries: A handbook of existential psychotherapy. Routledge.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

0 Comments