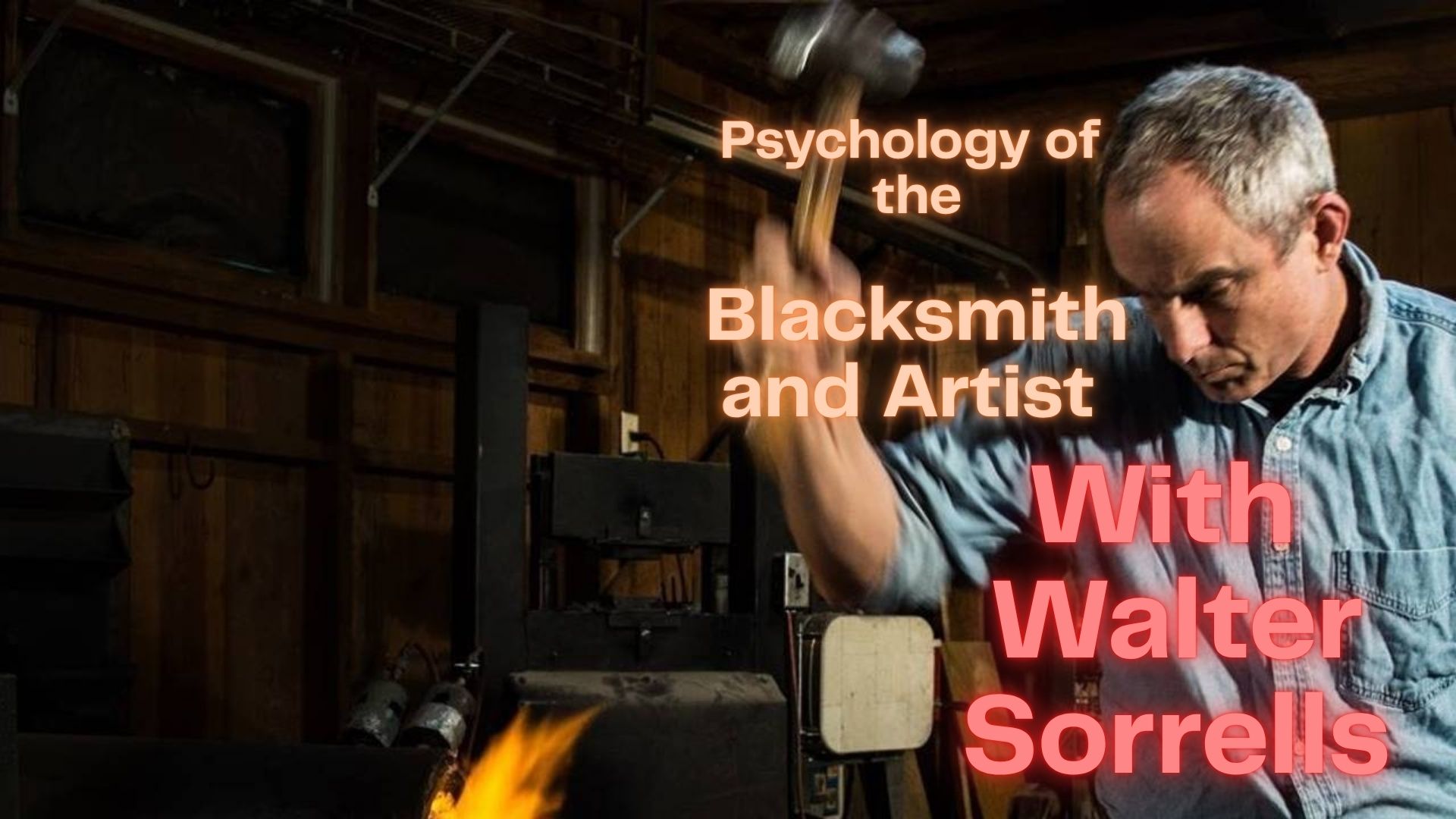

In a recent episode of the Taproot Therapy Collective podcast, therapist Joel Blackstock sat down with Walter Sorrells, a master swordsmith and knife maker based in Atlanta, for a conversation that cuts deep into the psychology of artistic development, personal growth, and the transformative power of dedicated craftsmanship.

The Unexpected Journey: From Novelist to Swordsmith

Walter Sorrells’ path to becoming a renowned maker of Japanese swords began in the most unexpected way. As a successful mystery novelist with multiple pseudonyms and decades of writing experience, Sorrells was researching a character for a new book—a swordsmith. What started as hands-on research to understand his character’s craft became a life-changing obsession.

“I really just farted around and I got the bug like that. It just hit me like a hammer,” Sorrells recalls. This immediate, visceral connection to the craft led him to spend the next 15 years essentially working two full-time jobs—writing in the mornings and forging until midnight.

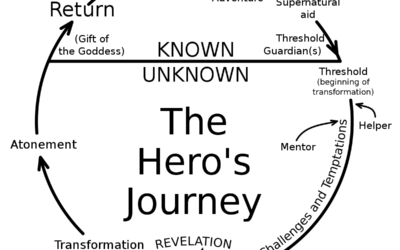

The Psychology of Transformation Through Practice

One of the most striking insights from the conversation is Sorrells’ perspective on personal development. When asked about how his artistic journey has changed him psychologically, his response challenges common assumptions about self-improvement:

“I always tell people that I am the exact same person I was when I was 13 years old. What I feel like my life has been about is not changing who I am in any serious way, but in becoming more effective at making my 13-year-old self move through the world.”

This perspective aligns beautifully with Blackstock’s therapeutic philosophy. As he notes to his patients, true growth often isn’t about discovering something new about yourself, but rather “figuring out how to go back to who you always knew you were, but be less ashamed of that and more effective at that in the world.”

The Martial Arts Connection: Learning How to Learn

Sorrells’ background in martial arts—20 years of karate, nearly a decade of Shinkendo (Japanese sword art), and Brazilian jiu-jitsu—provided crucial foundations for his craft. But perhaps more importantly, it taught him something fundamental about learning itself.

“One of the things that I feel like I learned the most from martial arts was how to learn how to do stuff,” he explains. The structured, sequential approach of martial arts training helped him overcome his natural tendency toward “undirected” learning, making him more effective in acquiring new skills.

Blackstock shares his own journey with Shinkendo, describing how the physical practice challenges psychological patterns: “Things like as simple as having to keep your weight forward… it really challenges my posture. I feel all this stuff kind of come up from childhood where I don’t feel like it’s safe to be assertive.”

The Art of Limitation: Finding Freedom in Constraints

Both men discuss how limitations—whether in materials, genre, or technique—can paradoxically lead to greater artistic freedom and authenticity. Sorrells learned this as a writer, discovering that narrowing his focus and working within genre constraints actually improved his work by “getting a lot of the noise out.”

This principle extends to Japanese sword making, where the limitations of traditional Japanese iron ore led to innovative techniques like differential hardening and the distinctive hamon (temper line) that makes these blades both functional and beautiful. As Blackstock notes, “The limitations of Japanese metallurgy are sort of what make it become what it is.”

The Sacred in the Mundane: Craftsmanship as Spiritual Practice

Sorrells offers a refreshing perspective on the nature of art and craftsmanship that strips away romantic pretensions: “If you went back another 100 or 200 years, you would find that virtually all artists consider themselves pretty close to guys that make chairs.”

This grounding in practical craftsmanship doesn’t diminish the spiritual dimension of the work. Drawing from Japanese martial arts and Buddhist philosophy, Sorrells emphasizes the importance of practice: “If you do a practice and you just do this thing and you don’t think about why you’re doing it… but you just do it with fullness and seriousness. Whatever your personality is will just manifest itself.”

The Technical as Gateway to the Transcendent

The interview delves into the intricate process of Japanese sword making—from the initial smelting of tamahagane steel to the complex clay tempering process that creates the sword’s distinctive curve and hardness differential. This technical mastery serves as a meditation on excellence and dedication.

Sorrells now primarily works with modern tools like CNC machines, creating knife-making tools and semi-production knives. Yet he maintains the same approach: total immersion in understanding materials and processes. “If you really dig into a particular material, it’s going to take you someplace,” he observes.

Lessons for Personal Growth and Therapy

Several key insights emerge from this conversation that apply beyond sword making:

- Authentic growth comes from becoming more effective at being who you already are, not trying to become someone else.

- Structured practice and accepting limitations can lead to greater creative freedom than trying to do everything at once.

- The path to mastery often involves embracing being a beginner and accepting the discomfort of incompetence.

- Physical practices can reveal and help work through psychological patterns in ways that pure introspection cannot.

- Finding work that engages both technical skill and aesthetic sensibility can provide deep satisfaction and meaning.

The Continuing Journey

At the heart of this conversation is a profound truth about human development: we grow not by escaping ourselves but by more fully inhabiting who we are. Whether through therapy, martial arts, or the patient forging of steel, the work remains the same—to face what is difficult, to persist through failure, and to find in that persistence a path to authentic self-expression.

As Sorrells puts it, happiness comes from “looking to the future and trying to find something interesting out there to move toward.” In the marriage of ancient technique and modern innovation, in the balance between form and function, and in the daily practice of craft, we find not just beautiful objects but a way of being in the world that honors both our limitations and our potential.

For those interested in exploring Sorrells’ work, you can find his Japanese swords at Walter Sorrells Blades, his production knives at Tactics Armory, and his knife-making tools at SorrellsTools.com. His extensive YouTube channel offers over 500 videos documenting his craft and teaching others the art of blade making.

0 Comments