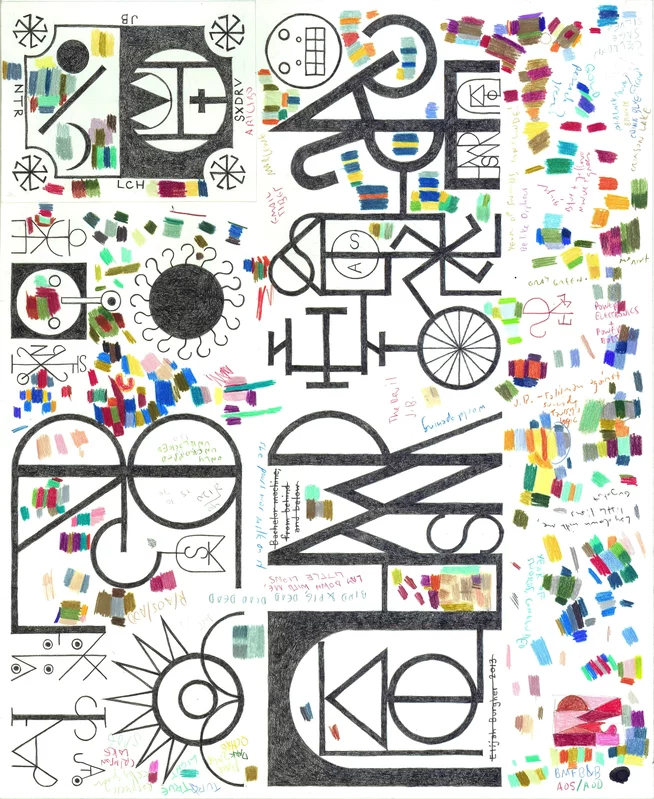

Elijah Burgher, Bachelor machine, from behind and below (Guyotat version), 2013 Elijah Burgher’s precisely detailed drawings and large, gestural drop-cloth paintings sit at the intersections of representation and language, imaginary and real worlds. All of his works, whether figurative and representational or symbol-based and abstract, merge personal narrative with magic, the occult, and queer aesthetics. Burgher’s finely wrought drawings are embedded with incantations and sigils—magical symbols in which the words of a spell are collapsed to abstraction—that weave together the artist’s desires for his own life, for those of his friends and colleagues, and for historical figures whom he sees as forefathers to his own art.

Humans split their own consciousness into the self and the other, enabling objective recognition.

-Mamoru Oshii, Director of the Ghost and the Shell.

Abstract and Key Points:

- Games, language, religion, and quantification abilities seem intrinsically linked to core human cognitive structures that likely co-evolved.

- Chomsky’s theories of innate universal grammar parallel the archetypal patterns and symbolic frameworks described by thinkers like Jung, Frazer, and Eliade.

- Games can be viewed as modes of “play” allowing creative exploration within these deep mental architectures for meaning-making.

- Religions represent profound “meaning games” utilizing humanity’s inborn symbolic faculties to grapple with existential mysteries.

- However, games and symbolic systems can also become pathological when taken to fundamentalist extremes, perpetuating trauma.

- Balanced integration of the linguistic-relational, objective-empirical, and subjective-mystical “games” of consciousness is vital for personal and societal well being.

- Transformative play and therapeutic modalities can cultivate self-awareness, resilience, and a sense of interconnectedness to navigate today’s complexities.

Are the Structures of Games and Language the Map to the Unconscious Mind?

Work is what a body is obliged to do. Play is what a body is not obliged to do.

-Mark Twain

One of the defining features of a game is that you don’t have to play it. Games are optional goals that we don’t have to do. Eating food or breathing isn’t a game because if you don’t do those things you die. A lizard does those things. Games are visible in social animals, play fighting, chasing the tail, hunting something that a cat knows is really a toy. Animals play games in semi conscious ways to learn new skills or practice usefully behaviors while humans might play remarkably nuanced and complicated games with elaborate rule sets. In the most primary structures of our consciousness, it might be our ability to play games that give us our humanity, creativity and intuition.

Games, in their myriad forms, seem to be one of our most primary and ultimate drives, serving as a means to stave off boredom and imbue our lives with meaning. Philosopher Bernard Suits suggests, if we were to solve every other human problem and find ourselves free from the constraints of necessity, we would likely turn to games as a conscious choice, a way to fill our time and engage our minds in a world without work or obligation. Because of this choice we would make with all limitations removed on our agency, Suits sees games as the very point of life, the primary drive that defines us as a species.

In Suits book, The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia he defines games as a way of voluntarily letting something else choose the conditions of our agency. Suits sees games as a system where players must freely choose to abide by arbitrary rules that set their objective. These rules define the means by which players are allowed to achieve a goal. Suits thinks that players adopt this attitude because they find the experience of playing the game inherently worthwhile.

When examining the parts of the psyche that seems to develop pre-consciously many of these first elements of consciousness seem to develop as a kind of game. Religion, language, and our ability to quantify or translate reality into numbers also appear to be originally rooted in game like elements.

When humanity first began to write the first two things we wrote were numbers and religious rites and ideas. Interestingly, the first written languages in many societies often revolved around either religious texts or the practical needs of taxation and record-keeping. The Sumerian cuneiform script, one of the earliest known writing systems, was used to record everything from hymns and prayers to inventories and receipts. Similarly, the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs were employed for both religious and administrative purposes. This suggests that our capacity for language, religion, and quantification may have co-evolved, each serving different but complementary functions in the development of human civilization.

Chomsky and the Innate Games of Language

Noam Chomsky, the influential 20th-century linguist, proposed the theory of generative grammar, which posits that human language is based on an innate, universal grammar hardwired into the brain. This “language acquisition device” (LAD) enables children to quickly learn the complex rules of their native language, despite receiving limited and imperfect input. Chomsky suggests that the LAD evolved as a unique human trait, providing an evolutionary advantage by facilitating complex communication and social interaction.

Chomsky’s language trees illustrate the hierarchical constituent structure of sentences, with words and phrases grouped together and labeled with syntactic categories. These trees reflect the binary branching nature of syntactic structure and the idea of transformations, where one tree structure can be derived from another through specific operations. Chomsky argued that the ability to form these hierarchical structures is innate and universal across human languages, a key aspect of his theory of Universal Grammar.

These deep linguistic structures could also be the basis for other forms of symbolic expression, such as myth, ritual, and art. The study of language games could provide insight into the deep structures of the human psyche. If these structures are innate, they may have evolved as a key adaptive trait of human cognition, with language games serving as cognitive exercises that keep our symbolic faculties sharp.

The same deep structures that enable language could also be responsible for other forms of symbolic expression and meaning-making, similar to Carl Jung’s archetypes. These structures provide a framework for generating and interpreting an endless variety of linguistic and symbolic expressions, allowing for flexibility and creativity within the rules of language or the archetypes of myth. Engaging with language or creating myths can be seen as a form of play—a way of creatively engaging with the symbolic tools provided by our innate mental structures.

Chomsky sees the way people across all cultures play with language through puns, word games, and double entendres as evidence supporting his theory. These linguistic play forms break the superficial rules of language while still obeying the deeper structural rules, demonstrating an intuitive understanding of the game-like nature of language that Chomsky believes is innate to all humans. This universal tendency to engage with language in creative and playful ways is a strong indicator that we are naturally drawn to language like a game, and that this predisposition is a fundamental part of human cognition.

Key points about Chomsky’s language trees:

Constituent structure:

Language trees illustrate the constituent structure of a sentence, i.e., how words group together to form phrases, and how phrases group together to form larger phrases or clauses.

Hierarchical organization:

The trees depict the hierarchical nature of language, with smaller units (words and phrases) nested within larger units (clauses and sentences).

Syntactic categories:

Each node in the tree is labeled with a syntactic category, such as noun phrase (NP), verb phrase (VP), or sentence (S). These categories reflect the grammatical function of the words and phrases they dominate.

Binary branching:

In Chomsky’s theory, language trees are typically binary branching, meaning that each non-terminal node splits into two branches. This reflects the idea that syntactic structure is fundamentally binary.

Transformations:

Chomsky also proposed the idea of transformations, where one tree structure can be derived from another through specific operations. This allows for the representation of complex grammatical phenomena, such as questions or passive sentences.

Universal Grammar:

Chomsky argued that the ability to form these hierarchical structures is innate and universal across human languages. This is a key aspect of his theory of Universal Grammar, which posits that all humans are born with a built-in capacity for language acquisition.

But what if these linguistic structures are more than just a framework for language? Could they also be the basis for other forms of symbolic expression, such as myth, ritual, and art? If so, the study of language games could provide a window into the deep structures of the human psyche.

Moreover, if these structures are innate, they must have evolved for a reason. Perhaps the ability to create and manipulate symbolic systems is a key adaptive trait of human cognition. Language games, in this view, could be seen as a kind of cognitive exercise or “game” that keeps our symbolic faculties sharp and ready for the challenges of communication and meaning-making.

The Language of Symbolism

The deep structures of the brain that Noam Chomsky proposes in his theories of language acquisition and use can indeed be seen as part of a larger “game” that humans play in creating and using not just language, but other symbolic systems like myth and religion. These are not dissimilar from the archetypes that Carl Jung describes.

Just as language trees illustrate the constituent structure and hierarchical organization of sentences, our thought processes could also be structured in a hierarchical manner. This hierarchical organization could allow us to break down complex ideas into smaller, more manageable components, enabling both objective and subjective thinking. Objective thinking would involve analyzing these components based on facts and logic, while subjective thinking would involve interpreting them through the lens of personal experiences, emotions, and beliefs.

The syntactic categories and binary branching in Chomsky’s language trees could be mirrored in the way our brains categorize and process information. Our thoughts could be organized into different categories, such as concrete or abstract, rational or emotional, which then combine in binary pairs to form more complex ideas. This structure could facilitate both objective and subjective thinking by allowing us to systematically process and analyze information from different perspectives.

Chomsky’s concept of transformations in language could be applied to the way our minds transform and manipulate ideas. Just as one linguistic tree structure can be derived from another through specific operations, our brains could use similar processes to transform concrete experiences into abstract concepts, or to derive new ideas from existing ones. This transformative capacity could be crucial for both objective problem-solving and subjective creative thinking.

These tendencies could be seen as a kind of “game” in the sense that they provide a set of rules and parameters within which we “play” with symbolic meaning. Just as the rules of a game create a structured space for play and creativity, the deep structures of the brain create a framework within which we can generate and interpret an endless variety of linguistic and symbolic expressions.

Moreover, these innate structures are not purely deterministic but allow for a great deal of flexibility and creativity. Within the rules of language or the archetypes of myth, there is still vast room for individual expression and innovation. In this sense, using language or creating myths can be seen as a form of play – a way of creatively engaging with the symbolic tools provided by our innate mental structures.

Wittgenstein and Language Games

This idea connects with the notion of “language games” proposed by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein suggested that language is not a single, monolithic system but a collection of different “games,” each with its own rules and purposes. Different forms of discourse, from everyday conversation to scientific inquiry to religious ritual, can be seen as different language games.

Extending this idea, we could see myth, religion, and other symbolic systems as “meaning games” that we play using the innate symbolic capacities of our brains and objective empirical tasks like science as “logic game” These games allow us to create shared narratives, explore existential questions, and imbue our lives with a sense of significance and purpose.

Furthermore, these meaning games, like language, are deeply social and inter-subjective. They are not played in isolation but are always embedded in a cultural and historical context. The specific forms they take are shaped by the collective experiences and values of a community. In this way, the deep structures of the brain interact with the social and cultural environment to generate the rich tapestry of human symbolic expression.

Wittgenstein’s concept of language games can be applied to science and religion, highlighting the different ways in which these forms of discourse approach the study of reality and the expansion of human knowledge.

This perspective suggests that the innate capacities of the human brain are not just for language but for meaning-making more broadly. The same mental tools that allow us to communicate with language also enable us to weave narratives, construct belief systems, and find patterns of significance in the world around us.

- Science as a Language of Objective Representation: Science can be seen as a language game that aims to understand how reality works through objective representation and empirical investigation. The language of science involves precise terminology, mathematical models, and rigorous methodologies designed to test hypotheses and measure observable phenomena.

The goal of the scientific language game is to create accurate, reliable, and verifiable descriptions of the natural world. Scientists engage in this language game by conducting experiments, collecting data, and analyzing results to develop theories and laws that can predict and explain natural processes.

Empiricism is a central tenet of the scientific language game, emphasizing the importance of observable evidence and experimentation in validating knowledge claims. Scientific concepts and theories are constantly tested against empirical data, and those that fail to match observations are revised or discarded.

- Religion as a Language Game of Subjective Experience and Self-Knowledge: Religion, on the other hand, can be understood as a language game that serves as a tool to explore subjective experience and increase our emotional and intuitive understanding of ourselves and the world. Religious language often employs paradox, metaphor, and symbolism to point towards truths that may be difficult to express in literal, objective terms.

The language game of religion recognizes that not all forms of knowledge can be reduced to empirical observation or logical analysis. By engaging with religious concepts, practices, and narratives, individuals can gain insight into their own inner states, values, and aspirations, as well as their relationship to the larger cosmos and the mysteries of existence.

Paradox and metaphor are central to the religious language game, as they allow for the expression of complex, multifaceted truths that cannot be fully captured by literal language. For example, the idea of God as both immanent and transcendent, or the self as both individual and part of a greater whole, are paradoxical notions that point towards the depth and complexity of subjective experience.

Through engaging with these paradoxes and metaphors, individuals can expand their emotional and intuitive understanding of themselves and the world, gaining a richer, more nuanced perspective on reality. Religious practices such as meditation, prayer, or ritual can serve as tools for cultivating this subjective knowledge and insight.

Are Games the Basis of Consciousness?

The concept of game-playing as a fundamental aspect of human consciousness is a fascinating area of philosophical and psychological inquiry. At the most basic level, our consciousness may be engaging with three primary types of games: objective/existential games, subjective/religious/mystical games, and logical/relational/linguistic games. These three domains could be seen as the basic building blocks of our consciousness, shaping the way we perceive and interact with the world around us.

One key question that arises from this perspective is whether these primary games of consciousness are truly “games” in the sense that Bernard Suits defines them. According to Suits, a game requires the voluntary acceptance of unnecessary obstacles and rules. If we cannot choose to think outside of these three domains, or if we engage with them automatically without agency, can they still be considered games?

This question touches on the deep issue of free will and determinism. If these three types of games are hardwired into our consciousness, are we truly free to choose how we play them? Or are we bound by the rules and structures of these games, with our choices and actions determined by the interplay of objective, subjective, and logical processes in our minds?

One possible resolution is to consider that free will may lie not in choosing the games themselves, but in how we play them. Within the constraints of these three domains, we may have the agency to apply, misapply, or combine them in unique ways. Our ethical choices and behaviors could be seen as the result of how we navigate and balance the sometimes-contradictory demands of objective reality, subjective experience, and logical reasoning.

This perspective aligns with current theories about the different types of memory and cognition in the brain. Over the course of evolution, our brains have developed specialized systems for processing sensory information (objective), emotional and autobiographical experiences (subjective), and abstract symbols and rules (logical/linguistic/relational). These systems work together to create our rich, multi-faceted experience of consciousness, but they can also come into conflict.

For example, psychological trauma often involves a contradiction between objective reality and subjective experience. A person may logically know that a threat has passed, but their emotional memory keeps them trapped in a state of fear and hypervigilance. In this case, the “game” of subjective experience overrides the “game” of objective reality, leading to dysfunctional patterns of thought and behavior.

Similarly, many psychological disorders involve distortions or imbalances in the way objective, subjective, and logical processes interact. Delusional disorders, for instance, may arise from giving too much weight to subjective experience while ignoring objective evidence and logical reasoning. Anxiety disorders often involve an overactive threat-detection system that perceives danger in objectively safe situations.

In this light, mental health could be seen as the ability to fluidly and adaptively navigate these different games of consciousness. By learning to recognize the rules and boundaries of each domain, and by developing strategies for harmonizing objective, subjective, and logical processes, we may be able to enhance our overall well-being and functionality.

Ultimately, the idea of game-playing as the primary condition of consciousness offers a rich framework for understanding the complexities of the human mind. While more research is needed to fully explore this concept, it provides a compelling lens through which to view the interplay of choice, constraint, and adaptation in shaping our mental lives. By recognizing the games we play, and by striving to play them well, we may unlock new levels of insight, creativity, and fulfillment.

The Paradox of the Ego and the Archetype

In his book “Ego and Archetype,” Edward Edinger explores the fundamental tension between the objective, existential ego mind and the subjective, mystical unconscious mind. He posits that these two aspects of the psyche are diametrically opposed and struggle to coexist within the same individual. The ego, rooted in the objective world, seeks to maintain a sense of separateness and control, while the archetype, emanating from the subjective realm, yearns for connection and unity with the larger whole.

This inherent conflict between the ego and the archetype can be seen as a reflection of the deeper paradox of human existence: the simultaneous experience of fundamental isolation and the desire for connection. As individuals, we are ultimately alone in our subjective experience, confined to the boundaries of our own minds. Yet, at the same time, we are driven by a profound longing for connection, belonging, and unity with others and the world around us.

Reconciling the Paradox: The Linguistic-Relational Game

The key to reconciling this paradox, according to Edinger, lies in the third primary game: the linguistic-relational realm. By engaging in the shared experience of language and relationships, we can bridge the gap between our isolated, individual existence and our yearning for connection and meaning.

Through the linguistic-relational game, we come to understand that we are all uniquely alone yet simultaneously connected through our common humanity. By sharing our stories, emotions, and experiences with others, we create a sense of community and belonging that transcends our individual isolation. This recognition of our shared struggle and the power of human connection serves as the ultimate game or connective tissue between the paradoxes of existential isolation and mystical desire for unity.

Engaging in the linguistic-relational game requires vulnerability, empathy, and a willingness to embrace the full spectrum of human experience. By openly communicating our thoughts, feelings, and experiences, we invite others to witness and validate our subjective reality while also gaining insight into their own. This process of mutual understanding and support allows us to navigate the challenges of existence with greater resilience, adaptability, and sense of purpose.

Ultimately, the linguistic-relational game serves as a crucial balancing force between the objective and subjective realms of our consciousness. By engaging in authentic, meaningful connections with others, we can bridge the gap between our isolated ego and our archetypal desire for unity, creating a more integrated and harmonious sense of self. As we learn to navigate the complexities of human relationships and communication, we develop the skills and insights necessary to engage with the full richness of our consciousness and find our place in the larger tapestry of human experience.

Balancing Language, Objectivity, and Subjectivity

The way our brain experiences consciousness can be understood as a process of entering into a limited form of agency or a game involving three primary components: language, objective experience, and subjective experience. These three aspects of consciousness, while distinct, are deeply interconnected and form the foundation of our mental life. As Edward Edinger points out, the larger game of consciousness involves walking a delicate balancing act between these three fundamental domains. Each domain represents a unique set of rules, challenges, and opportunities for growth and understanding, and our ability to navigate and integrate them effectively is crucial for our overall psychological well-being.

The game of language is perhaps the most obvious of the three, as it is through language that we are able to articulate, communicate, and reflect upon our experiences. Language allows us to create shared meanings, narratives, and cultural practices that shape our understanding of ourselves and the world around us. However, language is also inherently limited and can never fully capture the richness and complexity of our inner lives or the objective reality we inhabit.

The game of objective experience, on the other hand, involves our perception and interaction with the external world. Through our senses and cognitive faculties, we construct mental representations of the physical and social realities we encounter. This game requires us to constantly update and refine our understanding based on new information and feedback from the environment. However, our objective understanding is always mediated by our subjective biases, beliefs, and expectations.

The game of subjective experience is perhaps the most intimate and elusive of the three, as it encompasses our inner world of thoughts, feelings, and mental states. This game involves the ongoing process of self-reflection, introspection, and meaning-making that defines our sense of self and personal identity. However, our subjective experience is always shaped by the objective realities we encounter and the linguistic and cultural frameworks we use to interpret them.

Frazer, Eliade, and the Mythic Dimension of Games

James Frazer and Mircea Eliade were both influential scholars who explored the role of myth, ritual, and religion in human culture. While their approaches differed, both were interested in the idea of a “world navel” – a central point or figure that connected different realms of existence.

For Frazer, this idea was rooted in his concept of “sympathetic magic.” In his monumental work, “The Golden Bough,” Frazer argued that many myths and rituals across cultures were based on the principle that “like affects like.” In other words, by performing a symbolic action in one realm (such as a rain dance), people believed they could influence events in another realm (such as the weather). Frazer’s evolutionary biology is often wrong but his theories of rituals being an attempt to influence objective phenomenon through recreating subjective synchronicity are interesting to any discussion of games.

Central to many of these myths and rituals was the figure of the “sacred king” or “dying god.” This was a divine or semi-divine figure who was believed to embody the life force of the community. Through his ritualized death and rebirth, the sacred king was thought to ensure the renewal of nature and the continuity of life.

In Frazer’s interpretation, the sacred king served as a kind of “world navel” – a point of connection between the human world and the divine realm. By sacrificing himself and being reborn, the sacred king acted out a cosmic drama that was believed to have real effects in the world.

Mircea Eliade picked up on similar themes in his work, but he framed them in terms of the distinction between the sacred and the profane. For Eliade, all traditional cultures made a fundamental distinction between these two realms. The profane was the realm of everyday, mundane existence, while the sacred was the realm of the divine, the transcendent, the eternal.

Eliade argued that the role of myth and ritual was to create a bridge between these two realms. By participating in sacred rituals and recounting sacred myths, people were able to step out of profane time and space and connect with the sacred realm.

Like Frazer’s sacred king, Eliade’s “world navel” was a central point where the sacred and the profane intersected. This could be a physical location (like a temple or a sacred mountain), a sacred object (like a religious icon or a holy book), or a sacred person (like a priest or a shaman).

However, to shift from the stalemate of either/or to the possibilities of both/and requires archetypal support, and Jung feels that this shift is never achieived by human capacity alone.

The archetype of the Self, the figure of wholeness, needs to be constellated, to facilitate a comiing-together of the warring opposites. The Self, in turn, achieves its work by way of the ‘transcendent function’ (1916b), that function of the psyche that allows the opposites to be brought together and reconciled.

- David Tacey, Jung and the New Age

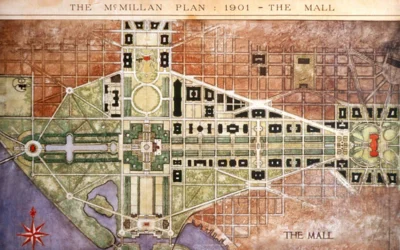

The “world navel” served as a kind of cosmic axis, a point of orientation around which the world was organized. By connecting with this central point, people believed they could tap into the power of the sacred and bring order to the chaos of the profane world. Eliade developed his theories observing uncontacted tribes of aboriginal people who organized all parts of their society around portable churingas or sacred rocs or sticks. The churinga mapped the center of order at the heart of the community and separated to world of the tribe, order from the chaos of the outside world. Eliade saw all religions as an attempt to build a central world navel as a kind of meaning making dome or sphere that separated order from chaos.

The ideas of Frazer and Eliade could be seen as mythic or religious expressions of a deep psychological truth – the need for a central point of connection and orientation in a world that is often experienced as chaotic, fragmented, or threatening. Whether in the realm of myth, religion, or psychology, the “world navel” serves as a powerful symbol of the human quest for meaning, order, and transcendence in the face of the unknown.

James Frazer and Mircea Eliade’s theories about myth, ritual, and the “world navel” can be seen as expressions of the three fundamental spheres of human cognition: the linguistic-relational, the objective-existential, and the subjective-mystical. These three cognitive domains, which form the basis of our conscious experience, are deeply interconnected and play a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the world and our place within it.

Frazer’s concept of “sympathetic magic,” which holds that symbolic actions in one realm can influence events in another, can be understood as a manifestation of the linguistic-relational sphere. Through the use of language and symbolic representation, humans create meaningful connections between otherwise disparate aspects of reality. The performance of rituals and the recounting of myths are, in essence, linguistic acts that serve to bridge the gap between the sacred and the profane, the human and the divine. By participating in these shared narratives and practices, individuals form bonds of social cohesion and create a sense of order and purpose in the face of the chaos and uncertainty of existence.

Eliade’s notion of the Axis Mundi, the central point of connection between the sacred and the profane realms, can be seen as a manifestation of the objective-existential sphere. The Axis Mundi represents a fixed point of reference in the midst of the flux and change of the phenomenal world. It serves as a reminder of the underlying unity and structure of reality, despite the apparent fragmentation and disorder of everyday experience. By orienting themselves around this sacred center, whether it be a physical location, a ritual object, or a mythical figure, individuals are able to situate themselves within a larger cosmic order and find meaning and purpose in their lives.

The subjective-mystical sphere is also evident in the theories of both Frazer and Eliade. The figure of the sacred king or dying god, which Frazer saw as central to many myths and rituals, represents the individual’s inner journey of transformation and renewal. Through the symbolic death and rebirth of this archetypal figure, individuals are able to confront and integrate the deeper, unconscious aspects of their own psyche. Similarly, Eliade’s emphasis on the experience of the sacred as a “wholly other” reality points to the subjective, ineffable nature of spiritual experience. By participating in sacred rituals and connecting with the Axis Mundi, individuals are able to transcend the limitations of their mundane existence and access a realm of heightened consciousness and spiritual insight.

In the Aboriginal Australian use of churingas, we see a powerful example of how these three cognitive spheres intersect and reinforce one another. The churinga serves as a linguistic-relational symbol, encoding the sacred stories and ancestral lineages of the individual and the community. It is also an objective-existential marker, a physical embodiment of the connection between the human and the divine realms. And finally, it is a subjective-mystical tool, a means of accessing altered states of consciousness and connecting with the spiritual essence of one’s being.

As Eliade recognized, the increasing collision of sacred spheres in the modern world poses both challenges and opportunities for our understanding of the nature of reality and our place within it. By recognizing the fundamental interconnectedness of the linguistic-relational, objective-existential, and subjective-mystical spheres, we can perhaps find new ways of integrating the insights of traditional wisdom with the demands of contemporary life. The “world navel,” in its various forms, remains a powerful symbol of the human quest for meaning, order, and transcendence in the face of the unknown. By honoring and cultivating our connection to this sacred center, we may yet find a way to navigate the complexities of our rapidly changing world with grace, wisdom, and compassion.

However, even in Eliade’s time, it was becoming apparent that these sacred spheres were not entirely isolated from one another. Eliade was studying how primitive tribes made meaning in a semi populated world and a monoculture. The modern world was much more complicated than rural Australia and would and is becoming vastly more complicated. As different cultures and religious traditions came into contact, their sacred spheres began to bump up against each other, creating a more complex and interconnected landscape of meaning. Eliade’s work gently, and perhaps unconsciously, acknowledged this increasing collision of sacred spheres.

The Language of Religion and the Religions of Language

Noam Chomsky’s theories of language, particularly his concept of a universal grammar innate to all humans, can indeed be seen as a linguistic exploration of the same fundamental human experiences that James Frazer and Mircea Eliade investigated through the lens of mythology and comparative religion.

At the heart of Chomsky’s linguistic theory is the idea that all human languages, despite their apparent diversity, share certain deep structural properties. These structures, Chomsky argues, are not learned but are hard-wired into the human brain. They form a kind of linguistic “operating system” that allows children to quickly and effortlessly acquire the specific language they are exposed to.

This idea of an innate linguistic structure parallels Frazer and Eliade’s concept of universal mythic patterns. Just as Chomsky posits a universal grammar underlying all human languages, Frazer and Eliade identified recurring themes and structures in the myths and religious practices of cultures around the world. These universal patterns, they argued, reflect fundamental aspects of the human psyche and our shared existential concerns.

For Frazer, the key universal mythic pattern was the story of the dying and resurrecting god, which he saw as a symbolic representation of the cycle of nature and the renewal of life. For Eliade, the universal pattern was the distinction between the sacred and the profane, and the human yearning to connect with the transcendent realm of the sacred through myth and ritual.

Chomsky’s linguistic theories can be seen as uncovering a similar deep structure in the realm of language. The universal grammar he describes could be understood as a kind of linguistic archetype, a fundamental pattern that shapes how we communicate and make meaning.

Moreover, Chomsky’s theory of transformational grammar, which describes how surface linguistic structures are generated from deep structures, can be seen as a model for how archetypal patterns are transformed into specific cultural expressions. Just as the deep structure of language generates an infinite variety of surface expressions, the archetypal patterns identified by Frazer and Eliade are manifested in a myriad of specific myths, rituals, and religious beliefs across cultures.

But the parallels between Chomsky’s linguistics and Frazer and Eliade’s mythological studies go beyond the identification of universal patterns. All three thinkers are, in a sense, grappling with the relationship between conscious and unconscious processes in human meaning-making.

For Frazer and Eliade, myths and religious practices are ways of engaging with the unconscious, of bringing into conscious awareness the deep, often hidden, patterns and impulses that shape human experience. Myths and rituals, in this view, serve to bridge the gap between the conscious and the unconscious, providing a way for individuals and communities to integrate and make sense of their deepest fears, desires, and existential concerns.

Chomsky’s linguistics can be seen as exploring a similar process in the realm of language. The deep structures he describes are not consciously known or learned, but operate at an unconscious level. It is only through the conscious study of language that these deep structures are brought to light.

In this sense, Chomsky’s work could be seen as a kind of linguistic archaeology, uncovering the hidden patterns and processes that underlie our conscious linguistic expressions. Just as Frazer and Eliade sought to uncover the unconscious patterns behind myths and religious practices, Chomsky’s linguistics aims to reveal the unconscious foundations of language.

This process of bringing the unconscious to conscious awareness is central to many psychological theories, particularly those influenced by the work of Carl Jung. Jung’s concept of individuation, for example, describes the lifelong process of integrating the unconscious aspects of the psyche into conscious awareness.

In this light, the work of Chomsky, Frazer, and Eliade can be seen as different approaches to the same fundamental human task: the integration of conscious and unconscious processes in the creation of meaning. Whether through the study of language, myth, or religious practice, these thinkers are all, in their own ways, trying to understand how we as humans bridge the gap between what we know consciously and what we sense unconsciously.

This bridging of the conscious and the unconscious is not just an academic concern, but a deeply personal and existential one. It is the task of making sense of our place in the world, of finding meaning and purpose in the face of life’s mysteries and challenges.

In the modern world, where traditional myths and religious practices may have lost some of their power, this task falls increasingly on the individual. We are each challenged to create our own sense of meaning, to find our own ways of integrating the conscious and the unconscious aspects of our experience.

In this context, the insights of thinkers like Chomsky, Frazer, and Eliade may be more relevant than ever. By revealing the deep patterns and processes that shape human meaning-making, they offer us tools for navigating the complexities of our inner and outer worlds. They remind us that, beneath the surface diversity of human culture and experience, there are universal structures and concerns that bind us together.

At the same time, the work of these thinkers also highlights the importance of individual expression and interpretation. Just as the universal grammar of language generates an infinite variety of specific utterances, the universal patterns of myth and religion find expression in a myriad of specific cultural forms. And just as each individual has their own unique way of using language, each person must find their own path to integrating the conscious and the unconscious, to creating meaning and purpose in their lives.

In conclusion, while Chomsky, Frazer, and Eliade were working in different fields and with different methodologies, their insights can be seen as converging on a common human truth: the deep, often unconscious, patterns and processes that shape how we make meaning in the world. Whether through language, myth, or religious practice, humans are constantly engaged in the task of bridging the conscious and the unconscious, of finding ways to express and integrate the deepest aspects of our experience.

In an increasingly complex and fragmented world, this task may be more challenging and more crucial than ever. The insights of these thinkers offer us not a simple solution, but a way of understanding the deep structures and processes at work in our quest for meaning. They invite us to engage consciously with the unconscious, to find our own ways of expressing and integrating the archetypal patterns that shape our lives.

In this sense, the linguistic theories of Chomsky and the mythological studies of Frazer and Eliade are not just academic exercises, but tools for living. They offer us a way of understanding ourselves and our world more deeply, of finding connection and meaning in the midst of diversity and change. As we navigate the uncertainties of the modern world, these insights may serve as a compass, guiding us towards a more integrated, more authentic way of being in the world.

Religion as a Game:

If we consider Eliade’s idea of religion as a means of accessing and participating in the sacred realm, we can draw a connection to Bernard Suits’ concept of games as the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles. In this view, religious rituals and practices can be seen as a kind of game, where participants voluntarily engage in certain actions and behaviors in order to access a different order of reality (the sacred). Just as games involve the acceptance of certain rules and limitations in order to achieve a specific goal, religious practices involve the acceptance of certain beliefs and behaviors in order to access the sacred realm.

The Point of Life as a Game:

If we combine these ideas, we can see human life as a kind of meta-game, where the goal is to navigate and integrate the various aspects of the unconscious (linguistic, sacred, interpersonal) into our conscious experience.

In this view, the various games we play – linguistic, religious, social – are all expressions of this larger, existential game of self-discovery and self-integration. Bernard Suits’ idea of gameplay as the essence of human existence can be understood in this context. Playing games with different type of knowledge are the basis of our consciousness. If life is a game, then the point is not just to win, but to play – to engage fully in the process of navigating the complexities of the unconscious and integrating them into our conscious experience.

Religion Uses Language to Unite the Subjective and Objective

Remember that in Chomsky’s theory, language is generated through a set of recursive rules that allow for the creation of an infinite number of sentences from a finite set of elements. These rules are represented as tree diagrams, with the trunk representing the most fundamental elements (e.g., noun phrases, verb phrases) and the branches representing the various modifications and transformations that can be applied to these elements.

Metaphors and poetic language can be seen as a “game” played within the boundaries of these underlying grammatical structures. Poets and writers manipulate the surface forms of language, deviating from the most literal or conventional meanings and constructions, while still adhering to the deeper structural rules that govern linguistic competence.

One fundamental idea here is that metaphor is itself a kind of game in the same way that religion is. Poetic and metaphorical and religious language uses its reference to point outside of itself and its own points of reference. In this way poetry, metaphor and religion can be seen as using language to describe a greater truth that we cannot “know” consciously, but that makes sense to the deep unconscious structures of implicit memory in the brain.

The game of poetry is using language “breaking the rules” while “obeying the rules” of language if you will. Humor and jokes are also using language to this end. This is why religious concepts usually paradoxical or absolute tensions. The Alpha and Omega, The Weak are strong, the poor are rich, etc. Reconciling the absolute tensions of our experience are the ultimate game.

In his book “The Weakness of God,” Philosopher and scholar of religion John Caputo introduces the idea of a messiah figure in religion who enters into a logical world of rules and laws to use metaphor, such as “I am bread” or “I am a lamb,” to point outside the rules of material reality to a realm of what he calls poetic anarchy. This concept highlights the transformative power of religious language and symbolism in breaking free from rigid, literal interpretations and opening up new possibilities for meaning and experience.

Caputo’s idea resonates with the notion that most major religions have a cosmology that reconciles a fundamental tension. In Christianity, for example, the existence of evil in a world created by a benevolent God is a central paradox that theologians have grappled with for centuries. The Christian narrative of the fall, redemption, and salvation can be seen as an attempt to resolve this tension, offering a framework for understanding suffering and injustice within a larger context of divine love and grace.

Similarly, in Gnosticism, the tension between the material world and the spiritual realm is a key theme. Gnostic cosmology often posits a dualistic universe, with the material world seen as a corrupt creation of a lesser, ignorant god (the Demiurge), while the true, spiritual reality is associated with a higher, unknowable God. The Gnostic path to salvation involves awakening to the divine spark within oneself and transcending the limitations of the material world to reunite with the spiritual source.

Religion has a long history of exploring truth through paradoxes and seemingly contradictory ideas. The Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity, which affirms the unity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as one God in three persons, is a prime example of a paradox that invites contemplation and wrestles with the mystery of the divine nature. Other examples include the Buddhist concept of emptiness (śūnyatā), which suggests that all phenomena are interconnected and lack inherent existence, and the Taoist principle of yin and yang, which emphasizes the complementary and interdependent nature of opposing forces.

These paradoxes and tensions in religious thought can serve as catalysts for spiritual growth and transformation. By engaging with these ideas through metaphor, ritual, and contemplative practice, individuals can break free from narrow, literalistic thinking and tap into a deeper, more expansive understanding of reality.

In the context of games and consciousness, religion can be seen as a type of “game” that helps individuals and communities navigate the complexities of existence and find meaning in the face of uncertainty and adversity. Like healthy gameplay, religion at its best encourages intellectual flexibility, emotional resilience, and a willingness to embrace paradox and mystery.

However, just as games can be used in unhealthy ways to perpetuate trauma and dogmatism, religion can also be co-opted by rigid, fundamentalist ideologies that shut down inquiry and growth. When religious ideas are taken too literally or used to justify oppression and violence, they become a deflectory game that hindered progress and well-being.

Destructive Games in the Modern World

Conspiracy theories are dangerous logic games that can provide an immersive and engaging alternate reality that offers a seductive clarity and simplicity compared to the ambiguities of real-world issues. They function similar to spirituality but, like all unhealthy games, help us deflect from internal and external realties instead of facing them. Like religion conspiracy theory is memetic, or engineered to be easily grasped and transferred from person to person, even without specialized knowledge, giving believers a sense of mastery over complex issues. However, unlike healthy gameplay, conspiracy theories don’t allow the believer to easily step out of the conspiratorial worldview, locking adherents into a fixed, narrow perspective that filters all new information to fit the conspiracy narrative.

Healthy games, on the other hand, allow for intellectual playfulness – the ability to try on different perspectives for fun and to flexibly shift between frameworks. When designed well, games can actually be an antidote or inoculation against the kind of narrow, hypergamified mindset that conspiracy theories promote, allowing practice in stepping into and out of different frameworks of meaning.

This distinction between healthy and unhealthy games extends beyond just conspiracy theories. Cults, fanatical literal religion, and fascist projection onto a strongman figure are all examples of unhealthy games that individuals and societies can play. These games serve as a way to double down on old trauma responses, preventing growth and change. By rigidly adhering to a singular worldview or ideology, individuals and groups can avoid confronting the complexities and uncertainties of reality, finding comfort in the false sense of security and certainty that these unhealthy games provide.

In contrast, healthy games help us master new skills, foster personal growth, and adapt to new situations. They encourage us to challenge our assumptions, explore different perspectives, and develop a more flexible and resilient sense of self. By engaging in healthy gameplay, we can learn to navigate the complexities of life with greater ease and creativity.

Understanding the primordial games that our early consciousness plays with language, numbers, and objective and subjective interior spaces can provide valuable insights into our fundamental motivations as humans. These games, which are deeply rooted in our cognitive and emotional development, shape the way we perceive and interact with the world around us.

For example, the game of language allows us to create shared meanings, narratives, and cultural practices that bind us together as social beings. However, when we take language too literally or rigidly, we risk falling into the trap of dogmatism or fundamentalism. Similarly, the game of numbers and quantification can be a powerful tool for understanding and manipulating the world around us, but when taken to an extreme, it can lead to a reductionist or mechanistic worldview that ignores the qualitative aspects of experience.

In the realm of religion and spirituality, the game of emotional judgment and meaning-making can provide a sense of purpose, connection, and transcendence. However, when religious beliefs are taken too literally or used to justify oppression or violence, they become an unhealthy game that perpetuates trauma and division.

To build a society that can solve these problems sustainably, we need to foster a culture of healthy gameplay that encourages intellectual flexibility, emotional resilience, and social responsibility. This involves creating educational and cultural institutions that promote critical thinking, empathy, and the ability to navigate complex systems.

One example of a deflectory game that hinders progress is the use of empiricism and quantification to avoid confronting the subjective and emotional dimensions of experience. By reducing everything to numbers and data points, we risk losing touch with the lived realities of individuals and communities. Similarly, the game of religious or ideological purity can lead to a rigid us-vs-them mentality that prevents collaboration and compromise.

On the other hand, healthy games that promote growth and understanding could include exercises in perspective-taking, where individuals are encouraged to step into the shoes of someone with a different background or worldview. Another example could be games that simulate complex social or ecological systems, allowing players to experiment with different strategies and outcomes in a safe and controlled environment.

Ultimately, the key to fostering a culture of healthy gameplay lies in recognizing the inherent limitations and biases of any single framework or perspective. By cultivating a sense of intellectual humility and curiosity, we can learn to hold multiple perspectives simultaneously, using them as tools for understanding rather than as rigid dogmas. This requires a willingness to step outside of our comfort zones, to engage with new ideas and experiences, and to continually challenge our assumptions about ourselves and the world around us.

By understanding the deep structures of consciousness and the games that shape our perceptions and behaviors, we can work towards creating a society that is more authentic, compassionate, and resilient. This involves recognizing the ways in which unhealthy games perpetuate trauma and division, while also cultivating the skills and frameworks necessary for healthy gameplay. It is through this process of self-reflection, experimentation, and growth that we can begin to create a world that reflects our deepest values and aspirations.

Integrating the Theories

The deep structures of consciousness that Noam Chomsky, James Frazer, and Mircea Eliade explored in language, myth, and religion can be understood as fundamental “games” that shape human perception and meaning-making. Chomsky’s concept of a universal grammar innate to all humans parallels Frazer and Eliade’s identification of universal patterns in myth and religious practice. These structures, operating largely unconsciously, provide frameworks within which humans “play” with symbolic expression.

In this context, games and play may take on new significance as spaces for exploring and integrating different modes of meaning-making. Drawing on the work of philosophers like Bernard Suits, as well as psychologists like Eric Berne, we can understand games as voluntary attempts to overcome unnecessary obstacles – a description that fits many religious and spiritual practices.

However, games and rule-based systems can also become traps, perpetuating trauma and limiting growth. To foster genuine transformation, we need to cultivate games that integrate the linguistic-relational, the objective-existential, and the subjective-mystical dimensions of human experience. This involves recognizing the ways unhealthy games perpetuate trauma and division, while developing games that promote self-awareness, perspective-taking, and a sense of interconnectedness.

The key is to approach games not as escapes from reality, but as tools for creatively engaging with it. In a world of information overload and competing truth claims, the ability to navigating and translate between different games may be an essential skill. By learning to play with different perspectives while maintaining a core sense of purpose, we can chart a course towards a new, more integrated understanding of ourselves and our place in the world.

Bibliography:

Berne, E. (1964). Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships. Grove Press.

Caputo, J. D. (2006). The Weakness of God: A Theology of the Event. Indiana University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Mouton.

Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt, Brace & World.

Frazer, J. G. (1890). The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion. Macmillan.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Nguyen, C. T. (2020). Games: Agency as Art. Oxford University Press.

Sloterdijk, P. (2011). Bubbles: Spheres Volume I: Microspherology. Semiotext(e).

Suits, B. (1978). The Grasshopper: Games, Life, and Utopia. University of Toronto Press.

Tacey, D. (2004). The Spirituality Revolution: The Emergence of Contemporary Spirituality. Brunner-Routledge.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Basil Blackwell.

Further Reading:

Bogost, I. (2016). Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games. Basic Books.

- Explores the philosophy of play and how games can infuse meaning into everyday life.

Caillois, R. (1961). Man, Play, and Games. University of Illinois Press.

- A classic study of the role of play and games in human culture.

Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Pantheon Books.

- Seminal work on the universal patterns and archetypes in world mythologies.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

- Influential book on the concept of “flow” and its relationship to happiness and fulfillment.

Flanagan, M. (2009). Critical Play: Radical Game Design. MIT Press.

- Examines the potential of games as a medium for social critique and change.

Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Groundbreaking study of the importance of play in human culture and civilization.

Koenig, H. G. (Ed.). (1998). Handbook of Religion and Mental Health. Academic Press.

- Comprehensive overview of the intersection of religion, spirituality, and mental health.

McGilchrist, I. (2009). The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press.

- Explores the differences between the left and right hemispheres of the brain and their impact on culture and society.

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. MIT Press.

- In-depth examination of game design principles and their broader cultural implications.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1997). The Ambiguity of Play. Harvard University Press.

- Explores the complex and multifaceted nature of play across different cultural contexts.

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine Publishing Company.

- Influential work on the role of ritual and liminality in cultural transitions and transformations.

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and Reality. Tavistock Publications.

- Classic work on the importance of play in childhood development and throughout life.

0 Comments