The Question You’ve Been Asking: “Could I Be Autistic?”

For many adults, the question arrives quietly at first, a gentle whisper that grows louder over time. It may surface after a conversation with a friend, after reading an article, or perhaps after a child or loved one receives a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).1 The question is often rooted in a lifelong feeling of being fundamentally different from those around you—a sense of navigating the world with a different set of instructions that everyone else seems to have been given.2 If this resonates, it is important to know that this exploration is not a search for a label or a “disorder,” but a courageous journey toward profound self-understanding and acceptance.3

In recent years, awareness of autism in adults has grown significantly. This is not because autism is a new phenomenon, but because for decades, it was poorly understood and often missed, especially in individuals who did not have a co-occurring intellectual disability or who were adept at concealing their differences.3 Many adults now questioning if they are autistic grew up in an era when the diagnostic criteria were narrower and focused almost exclusively on young boys exhibiting specific, overt behaviors. As a result, a large population of autistic individuals reached adulthood without the language to describe their experiences, often accumulating other diagnoses like anxiety, depression, or borderline personality disorder along the way.1

This journey of self-discovery is often catalyzed by a period of significant change or stress. The immense energy required to constantly adapt to a neurotypical world can lead to a state of profound exhaustion known as autistic burnout, where coping mechanisms fail and underlying traits become more apparent.4 A major life event—a new job, the birth of a child, a relationship ending, or even the disruption of routine caused by a global pandemic—can deplete the reserves needed to maintain this adaptation, bringing long-unanswered questions to the forefront.5 This article is intended to serve as a compassionate, evidence-based guide for that exploration, translating clinical knowledge into the context of lived experience.

Understanding the Autistic Brain: Core Traits in Adulthood

Autism is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition, meaning the brain is structured and processes information differently from the non-autistic (or neurotypical) brain.6 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), the standard classification used by clinicians, an autism diagnosis is based on the presence of characteristics in two core areas.7 It is not about a checklist of quirks, but about a persistent pattern of experiences that significantly impacts one’s life.

The Social Landscape: Differences in Social Communication and Interaction

This domain goes far beyond simple shyness or social anxiety. It describes a fundamental difference in the innate wiring for social engagement. For many autistic adults, social situations can feel like an intricate play for which they have never seen the script.6

- Social-Emotional Reciprocity: This refers to the natural back-and-forth of social interaction. Challenges in this area can manifest as difficulty initiating or sustaining conversations, not knowing when it is one’s turn to speak, or sharing information in a way that feels one-sided.10 The “social chitchat” that seems to come easily to others can feel pointless or confusing.12

- Nonverbal Communication: A great deal of neurotypical communication is unspoken, conveyed through body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice. Autistic individuals may find it difficult to interpret these subtle cues or to use them in a way that others easily understand.10 This can include difficulty maintaining eye contact (which may feel invasive or overwhelming), using a monotone or unusual vocal pitch, or not realizing one’s facial expression does not match their internal emotion.5

- Developing and Maintaining Relationships: Building and keeping friendships can be challenging. This is often not due to a lack of desire for connection, but rather a difficulty in navigating the complex, unwritten “rules” of social engagement.6 An autistic person might not understand certain social norms, leading them to be perceived as blunt, rude, or uninterested without any intention to be so.9 Their communication style is often direct and literal, which can be misinterpreted by those who rely on nuance and subtext.5

A World of Patterns, Routines, and Passions: Restricted, Repetitive Patterns of Behavior, Interests, or Activities

This second core domain is often misunderstood. From a neurodiversity-affirming perspective, these characteristics are not deficits but are integral to the autistic way of being, serving as powerful tools for regulation, joy, and coping in a chaotic world.

- Stereotyped or Repetitive Movements, Speech, or Use of Objects: Commonly known as “stimming,” these behaviors can include hand-flapping, rocking, spinning, or repeating words and phrases (echolalia).10 Far from being meaningless, stimming is a vital self-regulation strategy used to manage sensory input, express emotions (both positive and negative), and maintain focus, especially during times of stress or excitement.10

- Insistence on Sameness and Inflexible Adherence to Routines: Predictability can be a profound source of comfort and safety for the autistic brain. Having a consistent daily routine provides a stable structure that makes the world feel more manageable.9 Consequently, unexpected changes—even small ones like a different route to work or a canceled plan—can cause significant distress and anxiety.11 This is not a matter of stubbornness, but a genuine disruption to the cognitive and emotional equilibrium.

- Highly Restricted, Fixated Interests: Often called “special interests,” this refers to a deep, passionate, and highly focused interest in specific subjects or activities.10 These interests can range from train schedules and mathematics to a particular TV show, historical period, or scientific field. They are a source of immense joy, expertise, and comfort, and represent a state of optimal focus and engagement for the autistic mind.9

- Hyper- or Hypo-reactivity to Sensory Input: The sensory experience of an autistic person can be dramatically different from that of a neurotypical person. This can involve both heightened sensitivity (hyper-reactivity) and reduced sensitivity (hypo-reactivity) to sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures.7

The Sensory Experience

The autistic brain’s unique processing of sensory information is a critical aspect of the lived experience.

- Hypersensitivity can mean that the hum of fluorescent lights is deafening, the texture of a certain fabric is physically painful, a light touch feels jarring, or ordinary smells are overwhelming.10 This can lead to a state of “sensory overload,” where the brain becomes overwhelmed and unable to process any more information, potentially resulting in a meltdown (an intense outward expression of distress) or a shutdown (an internal withdrawal and loss of function).10

- Hyposensitivity, on the other hand, can manifest as a high tolerance for pain or temperature, a need for intense flavors, or a desire for deep pressure and strong sensory input.10 This can lead to sensory-seeking behaviors, like smelling objects or enjoying loud music, as a way to feel regulated and present in one’s body.10

These two core domains are not disconnected phenomena. The brain’s intense focus on patterns and details (a hallmark of Domain B) is the very same processing style that can make the unpredictable, nuance-filled social world (Domain A) so challenging to navigate. In this light, the reliance on routines, the deep dive into special interests, and the self-regulation of stimming can be understood as intelligent and adaptive responses to the inherent difficulties of living in a world not designed for the autistic neurotype.

The “Lost” Autistics: Masking, Burnout, and the Female Profile

A common question from adults considering an autism diagnosis is, “If I am autistic, how did everyone—including me—miss it for so long?” The answer often lies in a complex and exhausting survival strategy known as masking or camouflaging.5

Masking is the conscious or subconscious suppression of natural autistic traits and the performance of neurotypical behaviors in order to fit in and be accepted.5 It is a strategy born from a lifetime of social feedback, both subtle and overt, that one’s natural way of being is “wrong.” This can look like:

- Forcing eye contact during conversations, even when it is physically uncomfortable or distracting.5

- Manually scripting conversations in one’s head before or during social interactions.17

- Mimicking the facial expressions, gestures, and speech patterns of others.5

- Suppressing the urge to stim, perhaps replacing a larger movement like hand-flapping with a smaller, less noticeable one like tapping a finger or foot.5

- Pushing through extreme sensory discomfort in loud or crowded environments to appear “normal”.10

While masking can help an autistic person navigate school, work, and relationships, it comes at a tremendous cost. The constant self-monitoring and performance is mentally and emotionally draining, leading to chronic fatigue, anxiety, and depression.4 It creates a profound disconnect between the authentic inner self and the performed outer self, leading to feelings of isolation and being fundamentally misunderstood, even by those who are closest.1 This sustained effort is a primary contributor to autistic burnout, a state of intense exhaustion where the energy to continue masking is depleted, often leading to a regression in skills and an increase in autistic traits.4

This phenomenon of masking is particularly prevalent in autistic women and girls.9 Societal expectations often pressure females to be more socially adept and accommodating, which can drive a more intense and effective mask from a young age. As a result, the “female autistic profile” can present differently. Autistic women may be quieter, have more socially acceptable special interests (e.g., literature, psychology, animals), and show fewer obvious repetitive behaviors.9 Their social difficulties may be more internal—a constant state of anxiety and analysis in social situations—rather than externally apparent. This often leads to misdiagnosis, with clinicians seeing the resulting anxiety or depression but missing the underlying neurodevelopmental cause.1 This is not a social strategy but a trauma response to years of social rejection and the pressure to conform, which is why uncovering the autistic identity can be both a relief and a painful process of reclaiming a lost self.

An Informal Exploration: 30 Questions to Reflect On Your Experiences

Before proceeding, it is essential to understand the purpose of this section. The following questions are presented as an informal screener for self-reflection only. This is not a diagnostic tool, and the results do not constitute a formal evaluation or medical advice.18 The questions are adapted from well-researched, evidence-based clinical screening instruments to provide a structured way for you to explore your own experiences and traits in relation to the common characteristics of autism in adults. The goal is not to achieve a score, but to gather personal insight that may be helpful in a conversation with a qualified professional.

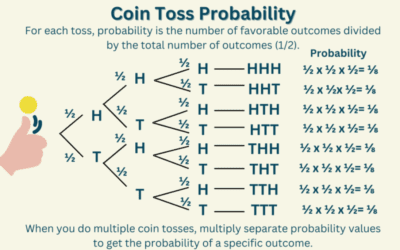

Several validated screening tools are used in clinical and research settings to measure autistic traits. Understanding them can provide context for this informal exercise.

| Tool Name | Number of Items | Key Domains Measured | Intended For |

| Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) | 50 | Social Skill, Attention Switching, Attention to Detail, Communication, Imagination 20 | Adults with average or above-average intelligence 21 |

| Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale–Revised (RAADS-R) | 80 | Social Relatedness, Circumscribed Interests, Language, Sensory-Motor 17 | Adults (18+) who may have developed coping strategies or masked their traits 17 |

| Aspie Quiz | 119 | Talent, Perception, Communication, Relationships, Social 23 | Adults (16+) with an IQ in the normal range 23 |

Instructions

For each statement below, reflect on your life experiences, both now and in the past. Choose the response that best describes how strongly the statement applies to you. Be honest with yourself; there are no right or wrong answers.

Response Options:

- This describes me very well.

- This describes me somewhat.

- This does not describe me.

The 30-Question Screener

Social & Communication Experiences

- I find it hard to make new friends or maintain long-term friendships.

- In social gatherings, I feel awkward and often don’t know how to act.

- I frequently find that I don’t know how to start or keep a conversation going.

- People have told me that what I’ve said is impolite or rude, even when I didn’t mean for it to be.

- I find it difficult to understand what other people are thinking or feeling just by looking at their face or body language.

- I take things very literally and can have trouble understanding sarcasm, idioms, or “reading between the lines.”

- I prefer to socialize with others who share my specific interests.

- I find “small talk” or social chitchat to be confusing and exhausting.

- I am often surprised when others tell me my tone of voice was inappropriate for the situation.

- I feel more comfortable interacting online or via text than in person.

Patterns, Interests & Routines

11. I prefer to do things the same way over and over again.

12. It causes me significant distress or anxiety if my daily routine is disturbed.

13. I have very strong, intense interests in specific topics, and I can spend hours focused on them.

14. I get very upset if I am interrupted or unable to pursue my special interests.

15. I notice patterns, details, or connections in things that others often miss.

16. I have a good memory for details, dates, or strings of information (like license plates or phone numbers).

17. I like to plan things carefully before doing them and dislike spontaneity.

18. I enjoy collecting or categorizing information about things.

19. When I talk, it can be difficult for others to get a word in if the topic is one of my interests.

20. I feel a strong attachment to certain objects, and it would be distressing to lose them.

Sensory & Internal Experiences

21. I often notice small sounds, faint smells, or subtle visual details that others do not.

22. I find certain everyday sounds (like a vacuum cleaner or chewing) to be physically painful or overwhelming.

23. Certain textures of food, clothing, or objects feel unbearable to me.

24. I sometimes have to isolate myself in a quiet, dark space to recover from being overwhelmed.

25. Conversely, I may have a high tolerance for pain or not notice when I am hot or cold.

26. I find it difficult to imagine what it would be like to be someone else.

27. When reading fiction, I find it hard to track the characters’ intentions or motivations.

28. I often engage in repetitive movements (like rocking, pacing, or fidgeting) to calm myself down or to focus.

29. I feel clumsy or uncoordinated compared to other people.

30. New or unfamiliar situations make me feel very anxious.

Interpreting Your Reflections

Once you have completed the screener, take a moment to look at your responses.

- Scoring: For a simple numerical reflection, you can assign 2 points for every “This describes me very well,” 1 point for “This describes me somewhat,” and 0 points for “This does not describe me.”

- A score of 30 or higher: A score in this range suggests that your personal experiences align with many of the common traits associated with autism in adults. This does not mean you are autistic. It does indicate, however, that further exploration with a qualified professional who specializes in adult autism assessment could be a valuable and validating next step.

- A score below 30: A score in this range may indicate that you experience some autistic traits, but perhaps not to the degree or consistency that would typically lead to a diagnosis. However, screeners are imperfect. If you strongly identify with the core concepts of autism despite a lower score, especially if you have a long history of masking, your experiences are still valid and worth exploring further.

Again, this is a tool for personal insight, not a verdict. Its primary value is in helping you organize your thoughts and provide a concrete starting point for a deeper conversation.

“I Think I Might Be Autistic. Now What?”

Reaching a point where you seriously consider the possibility of being autistic can be a watershed moment, often accompanied by a complex wave of emotions and questions about what to do next. This is a path of self-discovery, and there is no single “right” way to walk it.

Navigating the Emotional Aftermath

For many, the realization brings an overwhelming sense of relief. It can feel like finding the missing piece of a puzzle that explains a lifetime of struggles, misunderstandings, and feeling out of place.1 One late-diagnosed adult described it as re-evaluating their past and realizing, “actually I’m not a bad person, I’m not faulty”.1 This new framework can bring profound self-acceptance and self-forgiveness.

However, this relief is often mixed with other, more difficult emotions.3 There can be grief for the years spent struggling without understanding or support. There may be anger or resentment toward a world that did not recognize your needs.3 As one person shared, their journey was “a bit of a blessing and a curse,” acknowledging both the clarity and the pain of looking back.1 It is crucial to allow yourself space to process this full spectrum of feelings. You are not alone in this experience.

The Path to Clarity: Formal Diagnosis

The decision to seek a formal diagnosis is a deeply personal one with valid arguments on both sides.

- Potential Benefits: A formal diagnosis can provide definitive validation, ending years of uncertainty.4 It can grant access to legal protections and accommodations in the workplace or educational settings. It can also provide a clear framework for communicating your needs to family, partners, and healthcare providers, and can be a crucial step in accessing appropriate therapeutic support.4

- Potential Challenges: The path to diagnosis can be difficult. It can be expensive, waitlists for qualified assessors can be long, and there is a risk of encountering clinicians who are not experienced in adult autism, particularly in its masked or female presentations.4 Some also worry about stigma or discrimination after receiving a formal label.

A formal assessment for an adult typically involves a comprehensive diagnostic interview covering your developmental history from childhood to the present, direct observation of your social communication, and the use of standardized tools like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) or the Autism Diagnostic Interview, Revised (ADI-R).15 If you choose this path, it is vital to seek a clinician who explicitly states they have expertise in diagnosing adults.

Finding Your Community and Resources

Whether you pursue a formal diagnosis or not, one of the most powerful steps you can take is to connect with the autistic community.3 Finding others who share your lived experiences can be incredibly validating and can dramatically reduce feelings of isolation. It is a space to learn from peers, share strategies, and celebrate a shared identity.

The following organizations are reputable sources of information, community, and support for autistic adults. Many are run by and for autistic people, ensuring the resources are grounded in authentic experience.

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN): A national advocacy organization run by and for autistic people, focused on advancing the rights and inclusion of the autistic community. They provide resources on policy, rights, and self-advocacy.24

- Asperger/Autism Network (AANE): Provides extensive support and community for autistic individuals and their families, including support groups, coaching, and resources on a wide range of topics from employment to relationships.24

- Autism Society of America: A national organization with local affiliates that provides advocacy, education, and support services across the lifespan.24

- Madison House Autism Foundation: Focuses specifically on the needs of adults on the autism spectrum, working to promote solutions for housing, employment, and community inclusion.24

- Organization for Autism Research (OAR): Uses applied research to address the daily challenges faced by autistic people and their families, providing practical, evidence-based guides and resources.24

Embracing a New Understanding of Yourself

The journey of exploring whether you are autistic is, at its core, a journey toward authenticity. It is not about discovering what is “wrong” with you, but about finally understanding what is right and true about the way your brain works. This knowledge is a powerful tool. It allows you to reframe a lifetime of experiences through a lens of difference, not deficit.1 It gives you permission to stop expending enormous energy on masking and to start creating a life that accommodates your needs, honors your strengths, and celebrates your unique perspective.3

This path may involve unlearning decades of internalized criticism and forgiving yourself for not being able to meet neurotypical expectations. It may mean setting new boundaries, advocating for your sensory needs, and giving yourself the freedom to fully immerse yourself in the passions that bring you joy. Whether you seek a formal diagnosis or embrace a self-realized identity, this new understanding is an invitation to live a more genuine, compassionate, and sustainable life. It is the beginning of a new chapter—one written in your own language, on your own terms.2

Disclaimer

This article and the included screener are provided for informational and educational purposes only. They do not constitute medical advice, a psychological diagnosis, or a substitute for a formal evaluation by a qualified professional. The information presented is based on clinical research and diagnostic criteria but is not intended to be used for self-diagnosis. The informal screener is a tool for self-reflection designed to help you organize your thoughts and experiences. If you have concerns about your mental or physical health, or if you are seeking a diagnosis for Autism Spectrum Disorder, it is essential to consult with a qualified healthcare provider, such as a licensed psychologist, psychiatrist, or clinical social worker who has specific training and experience in assessing and diagnosing autism in adults.

References

- Attwood & Garnett. (n.d.). Experiences of Adults Diagnosed Autistic Later in Life. https://www.attwoodandgarnettevents.com/blogs/news/experiences-of-adults-diagnosed-autistic-later-in-life

- Autism Speaks. (n.d.). My story of being diagnosed with autism late. https://www.autismspeaks.org/life-spectrum/my-story-being-diagnosed-autism-late

- Psychology Today. (2023). Adult, Accomplished, Autistic: The Late Diagnosis Diaries. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/positively-different/202306/adult-accomplished-autistic-the-late-diagnosis-diaries

- Embrace Autism. (n.d.). The rise of late autism diagnoses. https://embrace-autism.com/the-rise-of-late-autism-diagnoses/

- Autism Speaks. (n.d.). Signs of autism in adults. https://www.autismspeaks.org/signs-autism-adults

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (n.d.). Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management.(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554918/)

- Autism Speaks. (n.d.). Autism diagnostic criteria: DSM-5. https://www.autismspeaks.org/autism-diagnostic-criteria-dsm-5

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Clinical Testing and Diagnosis for Autism Spectrum Disorder. https://www.cdc.gov/autism/hcp/diagnosis/index.html

- National Health Service. (n.d.). Signs of autism in adults. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/autism/signs/adults/

- Autism Speaks. (n.d.). Autism symptoms. https://www.autismspeaks.org/autism-symptoms

- Above and Beyond Therapy. (n.d.). Autism Diagnosis Criteria: DSM-5. https://www.abtaba.com/blog/autism-diagnosis

- Psychology Tools. (n.d.). Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ). https://psychology-tools.com/test/autism-spectrum-quotient

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute. (n.d.). Diagnostic Criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder in the DSM-5. https://www.research.chop.edu/car-autism-roadmap/diagnostic-criteria-for-autism-spectrum-disorder-in-the-dsm-5

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/autism/what-is-autism-spectrum-disorder

- National Autistic Society. (n.d.). Criteria and tools used in an autism assessment. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/diagnosis/assessment-and-diagnosis/criteria-and-tools-used-in-an-autism-assessment

- Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. (n.d.). IACC Subcommittee Diagnostic Criteria – DSM-5. https://iacc.hhs.gov/about-iacc/subcommittees/resources/dsm5-diagnostic-criteria.shtml

- NovoPsych. (n.d.). RAADS-R Test – Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale Revised. https://novopsych.com/assessments/diagnosis/ritvo-autism-asperger-diagnostic-scale-revised-raads-r/

- Clinical Partners. (n.d.). Online Assessment for Adult Autism. https://www.clinical-partners.co.uk/for-adults/autism-and-aspergers/adult-autism-test

- Exceptional Individuals. (n.d.). Autism Test | Am I Autistic Quiz | Free & Online. https://exceptionalindividuals.com/candidates/neurodiversity-resources/neurodiversity-quizzes/autism-quiz-test/

- NovoPsych. (n.d.). AQ – Autism Spectrum Quotient Test. https://novopsych.com/assessments/diagnosis/autism-spectrum-quotient/

- NeuroDirect. (n.d.). Autism Quotient (AQ) Test – Free Online Self-Assessment. https://neurodirect.co.uk/screening-tests/online-autism-tests/autism-quotient-test/

- Prosper Health. (n.d.). The RAADS-R: Autism Self-Assessment for Adults. https://www.prosperhealth.io/test/the-raads-r

- Embrace Autism. (n.d.). The Aspie Quiz. https://embrace-autism.com/aspie-quiz/

- Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. (n.d.). Private and Non-Profit Autism Organizations. https://iacc.hhs.gov/resources/organizations/private/

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

0 Comments