Encyclopedia of Norse Myth for Depth Psychology and Comparative Religion

Norse mythology, the pre-Christian religious beliefs and legends of the Scandinavian peoples, offers a rich tapestry of gods, goddesses, heroes, and cosmic events that continue to captivate the modern imagination. Yet compared to the well-known and widely worshipped deities of ancient Greece and Rome, the gods of the Norse often feel more enigmatic, their stories more fragmentary and elusive.

This sense of mystery is partly due to the nature of our sources. Unlike the Greeks, the Norse left behind no grand epics or plays as enduring vehicles for their myths. Instead, our knowledge relies on later works like the Poetic Edda, a collection of anonymous poems, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by the Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson. These texts were recorded centuries after the old Norse religion had given way to Christianity, by writers often unsure of the myths’ original pagan meanings.

A Mythic Worldview of Fate and Struggle

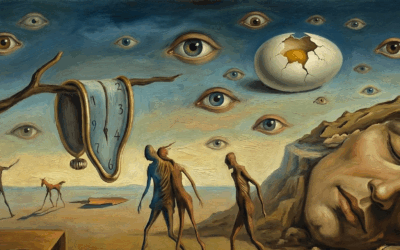

The tone of Norse myth is often somber, in sharp contrast to the humanism and celebratory spirit of much Greek mythology. While Greek myths tend to revolve around the exploits of an unruly but relatable pantheon, Norse mythology casts gods and humans alike as players in a grand cosmic drama shadowed by fate and doom.

We see this in the Norse vision of creation and destruction:

- The cosmos is born not from divine will, but from the elemental clash of fire and ice in the primordial void of Ginnungagap.

- The world is fated to end in Ragnarök, a cataclysmic battle in which even the gods will perish.

Between these mythic poles, the Norse gods enact a precarious balance:

- The pantheon is centered on the great ash tree Yggdrasil, which connects the various realms but is perpetually under threat.

- Odin, chief of the gods, seeks wisdom to stave off Ragnarök, but is ultimately bound by the larger web of fate.

The Gods and Forces of the Norse Cosmos

The major deities of the Norse pantheon embody powerful archetypal forces:

Odin,

the Allfather, god of wisdom, poetry, and battle fury

Thor,

the thunderer, champion of the gods and scourge of giants

Freyr and Freyja,

the Vanir deities of fertility, beauty and magic

Heimdall,

the vigilant guardian of the gods’ stronghold

Tyr,

the one-handed god of war and justice

Yet unlike the vivid personalities of Olympus, the Norse gods often feel more remote, more symbolic. Their myths are less character-driven narratives than glimpses of vaster impersonal forces – the cycles of nature, the inevitability of change, the balance and imbalance of order and chaos.

Loki: The Ambiguous Trickster

The most ambiguous figure in the Norse pantheon is undoubtedly Loki. Part god, part giant, Loki’s fluid allegiances and shapeshifting powers make him an agent of chaos and transformation. His exploits are integral to many key mythic events, yet he belongs fully to neither gods nor giants, and his ultimate role is to help precipitate Ragnarök.

Loki’s slippery nature points to the complex view of good and evil in Norse myth. Unlike the Manichean dualism often seen in mythology and religion, the Norse worldview understands chaos, conflict and destruction as part of the natural order, the necessary dark to the light. Loki personifies this understanding.

Entering the Norse Mythic Mindscape

To engage with Norse mythology, then, is to enter a symbolic world in many ways more challenging than the mythologies of sunnier climes. The Norse mythic landscape is one of harsh beauty, where the familiar polarities of light and dark, summer and winter, life and death dance to the somber rhythms of fate. The gods here are more elemental than Olympian – less distinct personalities than living embodiments of the forces that shape the worlds.

Yet for all its strangeness, Norse myth cuts to the bone of the human condition. In the struggle of gods and giants, order and chaos, we see mirrored our own struggles in a universe that often seems indifferent to human concerns. In the knowledge of Ragnarök, we confront the hard wisdom that all things, even the highest and mightiest, must ultimately yield to the turning of the great wheel.

It’s a worldview at once unsparing and profoundly humane – a mythic framework for understanding how fleeting and fragile are the structures of meaning we build against the void. And it’s this clear-sighted reckoning with the beautiful and terrible truths of existence that gives Norse mythology its enduring power.

A Gateway and a Guide

The pages that follow offer a gateway into this challenging but rewarding world. More than just a reference work, this dictionary aims to illuminate the living heart of Norse mythology – the perennial issues of meaning, identity, destiny that echo through these ancient tales.

In the spirit of the Norse mythic worldview, it does not seek to render these mysteries in bright Apollonian light, but to lead the reader into the half-lit halls of Valhalla, the misty groves of Yggdrasil – to offer a lantern in the twilight of the gods.

For in the end, these myths are not dead relics, but living symbols that speak to the deepest layers of the psyche. To grapple with Odin’s quest for wisdom, to hear the crowing of the cock that heralds Ragnarök, is to grapple with our own journeys of transformation in a world ever poised on the edge of revelation and ruin.

This dictionary, then, is both map and invitation – a guide to the gods and giants and cosmography of the Norse mythic universe, and a call to bring their meanings alive within your own psychological and spiritual experience.

May the wisdom of Mimir be yours at the well of memory. May you drink deep the mead of Odin’s poesy. And may you find in these pages not just the bones of Norse myth, but the blood and breath of living symbol and transformative truth.

Welcome to the world of the Norse gods – to the great ash and the rainbow bridge, to runic magic and writhing serpent, to elves and dwarves and giants and the coming of Ragnarök. Welcome to a myth-world strange and stern and glorious, where even in the midst of doom, the imperishable power of myth endures.

In the cosmography of Norse myth, the center cannot hold – and yet in the telling and retelling of these tales, something vital is reborn, the seed of meaning springs green from the ash.

May that ever-renewing power of myth kindle in your mind as you journey through these pages. And may the Norse gods rise from the page to stride through your dreams, living reminders of the magic and terror and grandeur of the mythic imagination.

Dictionary of Norse Mythology for Depth Psychology

Norse Mythological Figures and Their Psychological Significance

Odin

Mythological Background: Chief of the Aesir gods, Odin (also known as Wotan, Woden, or All-Father) was god of wisdom, poetry, death, divination, and magic. He sacrificed one of his eyes at Mimir’s well to gain wisdom and hung himself from the world tree Yggdrasil for nine days and nights, pierced by his own spear, to obtain knowledge of the runes. Odin led the Wild Hunt, gathered fallen warriors (einherjar) for his hall Valhalla, and was constantly preparing for Ragnarök, the doom of the gods. He was accompanied by two ravens, Huginn (thought) and Muninn (memory), two wolves, Geri and Freki, and rode the eight-legged horse Sleipnir. Despite his power, Odin knew through prophecy that he would ultimately be devoured by the wolf Fenrir at Ragnarök.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Hávamál, Völuspá); Prose Edda; Ynglinga saga; depicted in numerous archaeological artifacts.

Psychological Significance: Odin embodies the archetype of the seeker who willingly sacrifices comfort, safety, and even parts of himself for deeper knowledge and wisdom. His willingness to sacrifice his eye and to hang wounded on the world tree dramatizes the psychological truth that genuine consciousness requires painful surrender of partial perspectives and ego attachments.

From a Jungian perspective, Odin represents the Self in its dynamic aspect—constantly seeking integration of opposites and greater consciousness despite knowing of ultimate limitation (Ragnarök). His ravens symbolize the complementary psychological functions of active thought and stored experience, while his wolves represent how instinctual energies can serve consciousness when properly directed.

Odin’s dual nature as both wise ruler and wandering seeker illustrates the necessary tension in mature consciousness between established order and continued development—the psychological imperative to maintain structure while remaining open to transformation. His acceptance of inevitable doom represents the psychological capacity to pursue meaning despite awareness of mortality and limitation.

Clinical Applications: The Odin pattern emerges in individuals engaged in the lifelong pursuit of wisdom through willingness to sacrifice immediate comfort and conventional perspectives. In therapy, this presents as the capacity for necessary suffering in service of deeper understanding and integration. Working with this pattern involves helping clients distinguish between productive sacrifices that yield genuine insight and self-destructive patterns that merely deplete resources. The Odin archetype suggests how authentic psychological development requires both maintaining effective structures and remaining open to transformative encounters with the unknown.

Thor

Mythological Background: Son of Odin and the earth goddess Jörd, Thor was the immensely strong defender of Asgard and Midgard, primarily associated with thunder, lightning, storms, strength, and the protection of mankind. Unlike the aristocratic Odin, Thor represented the common man and farmers particularly revered him for his protection and association with fertile rains. He wielded the hammer Mjölnir, which returned to his hand when thrown, wore iron gauntlets and a belt of strength, and traveled in a chariot pulled by two goats that could be slain and resurrected. Thor’s greatest enemies were the giants (jötnar), whom he fought tirelessly. Despite his strength, Thor was characterized by both power and surprising vulnerability—nearly drowning when tricked into drinking from a horn connected to the sea, and ultimately fated to die at Ragnarök after slaying the world serpent Jörmungandr.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Þrymskviða, Hymiskviða); Prose Edda; depicted in numerous archaeological artifacts and place names throughout Scandinavia.

Psychological Significance: Thor embodies the archetype of embodied masculine power that defends boundaries and upholds natural order against chaotic forces. His hammer symbolizes the psychological function that both destroys what threatens integrity and consecrates legitimate structures—the capacity to discern and enforce necessary boundaries.

From a Jungian perspective, Thor represents the masculine principle in its aspect as protector and enforcer—the ego strength necessary to withstand threatening impulses from the unconscious (represented by giants) while remaining connected to both divine authority (Odin) and earthly reality (his mother Jörd). His chariot pulled by goats that can be consumed and resurrected symbolizes how vital instinctual energies can be repeatedly sacrificed and renewed in service of psychological work.

Thor’s combination of tremendous strength with occasional foolishness or vulnerability illustrates the psychological truth that even the most developed ego remains susceptible to deception and limitation. The stories of Thor being tricked or temporarily defeated serve as reminders of the ego’s necessary humility despite its legitimate power.

Clinical Applications: The Thor pattern emerges in individuals with strong psychological boundaries and protective capacity, particularly in their role of defending others from threatening energies. In therapy, this presents as the ability to establish and maintain appropriate limits while remaining vulnerable enough to learn from failure. Working with this pattern involves helping clients develop discernment about when to deploy protective strength and when to allow vulnerability, recognizing how both aspects serve psychological health. For individuals who primarily identify with vulnerability, developing Thor-like qualities may be an important aspect of psychological growth.

Loki

Mythological Background: A complex and ambiguous figure, Loki was a trickster deity who began as Odin’s blood brother and companion but gradually became the gods’ adversary. Neither fully god nor giant, but able to move between categories, Loki was characterized by his intelligence, shapeshifting abilities, and fundamentally ambivalent nature—sometimes helping the gods (retrieving Thor’s hammer, helping obtain treasures from the dwarves) and sometimes causing chaos (engineering Baldr’s death, insulting the gods at the feast of Aegir). Remarkably fluid in his identity, Loki not only changed forms but also gender, giving birth to the eight-legged horse Sleipnir after taking mare form. His offspring included monstrous beings who would threaten the gods at Ragnarök: the wolf Fenrir, the world serpent Jörmungandr, and the death-goddess Hel. After orchestrating Baldr’s death and verbally attacking all the gods, Loki was bound with the entrails of his son, with a serpent dripping venom onto his face, until his eventual escape at Ragnarök.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Lokasenna, Þrymskviða); Prose Edda; depicted in various archaeological artifacts.

Psychological Significance: Loki embodies the archetype of the trickster who catalyzes transformation through disruption of established patterns and boundaries. His nature transcends simple categories of good or evil, representing instead the psychological function that questions rigid structures and introduces creative chaos necessary for renewal.

From a Jungian perspective, Loki represents the shadow side of cultural consciousness—the repressed, creative, disruptive energies that both threaten collective identity and provide its necessary renewal. His shape-shifting abilities symbolize how these energies refuse containment within fixed forms, constantly adapting to circumvent established defenses. His increasing antagonism toward the gods represents the psychological principle that what is excessively repressed or controlled eventually returns in more destructive forms.

Loki’s role in obtaining treasures for the gods, despite his troublesome methods, illustrates how shadow energies often provide access to resources unavailable through conventional channels. His gender fluidity and literal motherhood of Sleipnir represent the psychological capacity to transcend fixed identity categories, accessing creative potential beyond limited self-conceptions.

Clinical Applications: The Loki pattern emerges in individuals who challenge established structures through wit, creativity, and sometimes disruptive behavior. In therapy, this presents as the capacity to question rigid psychological patterns that have outlived their usefulness, often through humor or unexpected perspectives. Working with this pattern involves distinguishing between creative disruption that serves growth and purely destructive acting out, helping clients channel trickster energy toward genuine transformation rather than mere chaos. For individuals overly identified with social conformity, conscious engagement with Loki-like qualities may be essential for psychological liberation.

Freyja

Mythological Background: Goddess of love, beauty, fertility, war, and death, Freyja was among the Vanir deities who joined the Aesir after their war. Sister (and possibly consort) to Freyr, daughter of Njörd, Freyja possessed remarkable magical powers, particularly in seiðr—a form of shamanic magic associated with fate and prophecy. She owned the necklace Brísingamen, acquired through spending nights with four dwarves, and a cloak of falcon feathers that allowed shapeshifting. Freyja rode a chariot pulled by cats and was attended by the boar Hildisvíni. As a death goddess, she received half the warriors slain in battle (the other half going to Odin), welcoming them to her hall Fólkvangr. Often pursued by giants, jötnar, and other beings who desired her, Freyja maintained her autonomy while being associated with both sensuality and fierce independence.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda; Prose Edda (particularly Gylfaginning and Skáldskaparmál); Heimskringla.

Psychological Significance: Freyja embodies the archetype of feminine power that integrates seemingly opposite qualities—sensuality and warfare, love and death, beauty and fierceness. Her multiple domains dramatize the psychological truth that the feminine principle contains numerous potentials beyond conventional stereotypes.

From a Jungian perspective, Freyja represents the anima in its complete rather than partial manifestation—the feminine aspect of the psyche that encompasses both nurturing and destructive qualities, both receptivity and assertive action. Her practice of seiðr symbolizes how this integrated feminine consciousness accesses knowledge through altered states and intuitive channels rather than solely through rational processes.

Her falcon cloak represents the psychological capacity for perspective shift—the ability to rise above immediate circumstances to gain broader understanding. Her acquisition of Brísingamen through nights with the dwarves symbolizes how engaging with chthonic or unconscious forces (the dwarves as earth-beings) yields spiritual treasures (the necklace) that enhance conscious identity.

Freyja’s role in receiving fallen warriors parallels Odin’s, suggesting the psychological principle that feminine consciousness has equal capacity to integrate and transform the consequences of conflict. Her persistent refusal to be possessed by giants or jötnar symbolizes the feminine psyche’s resistance to domination by unconscious collective forces.

Clinical Applications: The Freyja pattern emerges in individuals who integrate sensuality and spiritual power, receptivity and fierce boundary-setting, beauty and death-awareness. In therapy, this presents as the capacity to move fluidly between apparently contradictory feminine qualities rather than remaining identified with limited aspects. Working with this pattern involves helping clients recognize and claim the full spectrum of feminine potential, developing shamanic capacities to move between different states of consciousness, and maintaining autonomy while engaging deeply with others. For individuals overly identified with limited feminine stereotypes, conscious engagement with Freyja’s multiplicity offers liberation from restrictive self-conceptions.

Frigg

Mythological Background: Queen of Asgard, wife of Odin, and goddess of marriage, motherhood, and prophecy, Frigg possessed the power to know all fates though she seldom revealed what she knew. She was closely associated with the domestic arts, particularly spinning and weaving, which connected symbolically to her role in weaving fate. As mother of Baldr, she extracted promises from almost all living things not to harm her beloved son, tragically overlooking only the mistletoe, which Loki exploited to engineer Baldr’s death. After his death, she sent an emissary to Hel to attempt his retrieval, but one giantess (possibly Loki in disguise) refused to weep for Baldr, preventing his return. Though sometimes confused with Freyja due to their overlapping domains, Frigg represented more specifically the power of the legitimated wife and mother, rather than independent feminine sexuality.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá, Lokasenna); Prose Edda; Gesta Danorum.

Psychological Significance: Frigg embodies the archetype of maternal wisdom and protection that operates through foresight, preparation, and preservation of order. Her association with weaving symbolizes the psychological function that creates patterns of meaning and relationship, establishing coherence within family and social systems.

From a Jungian perspective, Frigg represents the mature feminine principle in its aspect as preserver of values and protector of vulnerable new developments (symbolized by Baldr). Her knowledge of fates without always revealing them represents the psychological pattern of holding awareness of difficult truths without prematurely exposing others to what they cannot yet integrate—the capacity for protective withholding.

Her attempt to protect Baldr by extracting promises from all beings represents the maternal impulse to create perfect safety for what is precious and vulnerable. The inevitable failure of this strategy—overlooking the seemingly insignificant mistletoe—symbolizes the psychological truth that no protective system can be complete; vulnerability always remains. Her grieving persistence in attempting Baldr’s rescue represents the psychological refusal to accept irrevocable loss.

The relationship between Frigg and Odin exemplifies the psychological partnership between feminine protective wisdom and masculine questing wisdom—complementary approaches to engaging with fate and uncertainty.

Clinical Applications: The Frigg pattern emerges in individuals who attempt to create safety and coherence through foresight, preventive action, and maintenance of order. In therapy, this presents as both the capacity for protective care and the potential overemphasis on control that can impede necessary risk and growth. Working with this pattern involves helping clients distinguish between appropriate protection and excessive shielding, developing capacity to hold knowledge of potential threats without succumbing to anxiety, and finding meaning beyond the inevitable failures of protective efforts. For individuals who have experienced profound loss despite their best preventive efforts, processing the Frigg-Baldr dynamic may be particularly healing.

Heimdall

Mythological Background: Guardian of Bifröst, the rainbow bridge connecting Asgard to other realms, Heimdall was born of nine mothers (possibly wave maidens) and possessed extraordinary senses—able to see for hundreds of miles by day or night and to hear grass growing on the earth and wool on sheep. He required less sleep than a bird and carried the horn Gjallarhorn, which he would sound at Ragnarök to alert the gods. His hall was Himinbjörg (“heaven’s castle”) positioned at the edge of Asgard. According to some sources, Heimdall established the hierarchical structure of human society, creating the classes of thralls, karls (freemen), and jarls (nobles). He was destined to slay and be slain by Loki at Ragnarök. In some accounts, he was also keeper of Freyja’s necklace Brísingamen, which he retrieved after Loki stole it.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá, Rígsþula, Þrymskviða); Prose Edda; depicted in archaeological contexts.

Psychological Significance: Heimdall embodies the archetype of the vigilant guardian who maintains boundaries between different domains of experience. His extraordinary senses symbolize the psychological function of heightened awareness that detects threats to integrity before they manifest fully—the capacity for early warning that preserves essential structures.

From a Jungian perspective, Heimdall represents the boundary-maintaining aspect of consciousness that distinguishes between different psychological territories and regulates traffic between them. His position at the rainbow bridge Bifröst symbolizes the capacity to facilitate appropriate communication between conscious and unconscious contents while preventing destructive flooding of consciousness by unconscious material.

His nine mothers suggest the multiple origins of psychological vigilance—how boundary awareness develops through diverse experiences of relationship rather than from a single source. His establishment of human social classes (if attributed to him) symbolizes how psychological differentiation creates necessary hierarchies of function and value, providing structure to both individual and collective experience.

Heimdall’s destined mutual destruction with Loki at Ragnarök represents the psychological principle that rigid boundary maintenance and boundary dissolution are complementary opposites that ultimately transcend each other in moments of systemic transformation.

Clinical Applications: The Heimdall pattern emerges in individuals with highly developed perceptual sensitivity and boundary awareness. In therapy, this presents as the capacity to detect subtle threats and maintain appropriate psychological distance from potentially overwhelming experiences. Working with this pattern involves distinguishing between necessary vigilance and hypervigilance that prevents genuine engagement, developing balance between boundary maintenance and openness to transformation, and recognizing when gatekeeping functions serve protection versus when they impede growth. For individuals who struggle with boundaries, developing Heimdall-like qualities may be essential for psychological safety.

Baldr

Mythological Background: Son of Odin and Frigg, Baldr was the most beautiful, beloved, and noble of the gods, associated with light, purity, joy, and reconciliation. After experiencing prophetic dreams of his death, his mother extracted promises from all things not to harm him, inadvertently omitting the mistletoe. The gods then made sport of throwing objects at the invulnerable Baldr, until Loki guided the blind god Höðr to throw a mistletoe dart, which killed Baldr instantly. His body was placed on a funeral ship with his wife Nanna, who had died of grief. When Hermóðr journeyed to Hel to retrieve him, the underworld goddess agreed to release Baldr if all things would weep for him. Only one giantess (possibly Loki in disguise) refused to weep, forcing Baldr to remain in Hel until after Ragnarök, when he would return to rule a renewed world.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá); Prose Edda; Gesta Danorum (in an euhemerized version).

Psychological Significance: Baldr embodies the archetype of pure potential and vulnerable innocence that cannot be preserved indefinitely in a world of necessary conflict and limitation. His story dramatizes the psychological necessity of integrating the experience of loss and mortality even regarding what seems most precious and perfect.

From a Jungian perspective, Baldr represents the pristine Self-image—the initial sense of infinite potential and specialness that must necessarily encounter limitation through developmental experience. His invulnerability to most weapons but fatal vulnerability to the overlooked mistletoe symbolizes how even the most protected psychological structures remain susceptible to apparently minor weaknesses.

The gods’ game of throwing weapons at the invulnerable Baldr represents the psychological testing of boundaries that often precedes significant breakthroughs or breakdowns. His death and descent to Hel symbolizes how cherished ideals and pristine self-conceptions must “die” into the unconscious to be transformed rather than remaining static objects of conscious attachment.

Baldr’s promised return after Ragnarök, to rule a renewed world, suggests how surrendered innocence can return in transformed form after the collapse of rigid psychological structures—how what appears irrevocably lost can reemerge when the conditions that necessitated its loss have been transcended.

Clinical Applications: The Baldr pattern emerges in experiences of essential goodness or potential that seems prematurely lost or destroyed despite protective efforts. In therapy, this presents in grief for unrealized possibilities—whether for oneself or for loved ones whose lives were cut short. Working with this pattern involves supporting the necessary mourning for what appears irrevocably lost while maintaining connection to the transformative potential contained within that loss. The Baldr story offers hope that what descends to the unconscious is not destroyed but preserved in latent form, potentially available for recovery under new psychological conditions.

Hel

Mythological Background: Daughter of Loki and the giantess Angrboða, Hel was goddess and ruler of the underworld realm that shared her name. Unlike Christian concepts of hell, Hel was not primarily a place of punishment but the destination for those who died of illness or old age rather than in battle (those who went to Odin’s Valhalla or Freyja’s Fólkvangr). Described as half flesh-colored and half blue-black, Hel embodied the dual nature of death as both natural process and fearsome transformation. Her realm contained both punitive regions for oath-breakers and relatively pleasant areas, suggesting a differentiated afterlife based on one’s conduct. She received Baldr after his death and set conditions for his potential release, though these were ultimately not fulfilled. Despite her fearsome aspects, Hel represented the natural and necessary end of mortal existence rather than malevolent destruction.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá); Prose Edda; Gesta Danorum.

Psychological Significance: Hel embodies the archetype of natural dissolution and the psychological necessity of surrender to processes beyond ego control. Her dual-colored appearance dramatizes the ambivalent nature of psychological surrender—simultaneously natural completion and fearsome transformation.

From a Jungian perspective, Hel represents the aspect of the unconscious that receives contents that have completed their conscious life cycle—the psychological function that allows for dignified completion rather than desperate prolongation. Unlike the violent “death” represented by Valkyries taking warriors to Valhalla (sudden, dramatic psychological transformation), Hel presides over the gradual, natural release of what has fulfilled its purpose.

Her realm’s differentiated nature—with areas of punishment for oath-breakers and more pleasant regions for others—symbolizes how the experience of surrender to the unconscious varies according to one’s relationship with psychological truth. Those who have violated their authentic nature experience this surrender as punitive, while those who have lived in accordance with deeper values experience it as relatively peaceful.

Hel’s complex lineage—daughter of the trickster Loki and giantess Angrboða, sister to the world serpent and the wolf Fenrir—connects her to primal forces beyond the established divine order. This genealogy suggests how psychological dissolution ultimately serves forces of renewal and transformation outside current conscious structures.

Clinical Applications: The Hel pattern emerges in experiences of surrender to natural endings—whether of relationships, careers, identities, or physical life itself. In therapy, this presents as the challenge of releasing what has completed its natural cycle without either premature abandonment or desperate prolongation. Working with this pattern involves developing capacity for dignified completion and recognition of how surrender to natural processes ultimately serves renewal, even when experienced as loss. For individuals facing terminal illness or accompanying loved ones through this process, engagement with Hel as natural completion rather than merely fearsome end can be particularly healing.

Tyr

Mythological Background: God of war, justice, and the thing (assembly), Tyr was noted for his courage and self-sacrifice. His most famous myth involves the binding of the monstrous wolf Fenrir, who threatened the gods. When the gods sought to restrain Fenrir with the unbreakable fetter Gleipnir, the wolf agreed to be bound only if one of the gods would place a hand in his mouth as a pledge of good faith. Knowing the binding was a trick, but recognizing the necessity of containing the wolf to preserve cosmic order, Tyr voluntarily placed his right hand in Fenrir’s jaws. When the wolf found himself trapped, he bit off Tyr’s hand. Despite this sacrifice, Tyr continued as a powerful god, embodying the principle that justice sometimes requires personal sacrifice. In some traditions, Tyr was originally chief of the gods before being supplanted by Odin, suggesting an evolution in Norse religious emphasis from lawful order to magical transformation.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda; Prose Edda; depicted in archaeological contexts, particularly through the Tiwaz rune that bears his name.

Psychological Significance: Tyr embodies the archetype of principled sacrifice—the willingness to surrender something valued for the sake of a greater good or necessary order. His lost hand dramatizes how adherence to principle often requires relinquishing capacity in other areas, particularly those associated with grasping and acquiring.

From a Jungian perspective, Tyr represents the psychological function that maintains ethical integrity even at significant personal cost—the capacity to serve transpersonal values rather than immediate self-interest. His sacrifice to bind Fenrir symbolizes how containment of destructive instinctual energies (the wolf) sometimes requires consciousness to relinquish part of its power or wholeness.

The replacement of Tyr by Odin as chief deity in some traditions suggests the psychological evolution from rigid adherence to established law (Tyr) toward more fluid engagement with transformation and inspiration (Odin)—the developmental shift from conventional morality to more individuated ethical consciousness.

Tyr’s continued effectiveness despite his lost hand represents the psychological truth that principled limitation can enhance rather than diminish authentic power. By accepting limitation in one domain (symbolized by the lost hand), consciousness gains authority and effectiveness in others.

Clinical Applications: The Tyr pattern emerges in individuals who make conscious sacrifices for ethical principles or collective welfare. In therapy, this presents as the capacity to accept necessary limitations for the sake of greater integrity or shared good. Working with this pattern involves distinguishing between productive sacrifice that serves genuine values and self-destructive surrender of capacity that serves neither self nor others. For individuals who struggle with containing destructive impulses, developing Tyr-like willingness to accept limitation for the sake of greater order may be essential for psychological development.

Njord

Mythological Background: God of the sea, winds, fishing, seafaring, and prosperity, Njord was among the Vanir deities who joined the Aesir after their war. Father of the twins Freyr and Freyja, he was associated with wealth and abundance, particularly that derived from the sea. In one significant myth, Njord married the giantess Skadi as compensation after the gods killed her father. Skadi chose Njord as husband by selecting his feet from a lineup, believing them to belong to the beautiful Baldr. Their marriage failed due to incompatible preferences—Njord could not tolerate the mountains where Skadi preferred to live, while she could not endure the sounds of the seashore that Njord loved. They separated amicably, each returning to their preferred environment. Njord’s character exemplifies balance, mediation, and the capacity to bring wealth from apparently chaotic environments (the sea).

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda; Prose Edda; Heimskringla; place names throughout Scandinavia.

Psychological Significance: Njord embodies the archetype of abundance derived from comfort with flux and change. His domain of the sea symbolizes the psychological capacity to navigate changing circumstances and extract value from apparently unstable conditions—the ability to find prosperity through adaptation rather than rigid control.

From a Jungian perspective, Njord represents the masculine principle in its nurturing, providing aspect rather than its confrontational or hierarchical manifestations. His association with the sea connects him to the unconscious in its positive, generative aspect—the psychological resources that emerge from comfortable engagement with depth rather than resistance to it.

His failed marriage with Skadi, despite their mutual respect, symbolizes the psychological challenge of integrating fundamentally different orientations—the tension between comfort with flux (Njord’s seashore) and preference for stark clarity (Skadi’s mountains). Their amicable separation represents the psychological wisdom of recognizing when certain internal elements function better with differentiation rather than forced integration.

Njord’s status as father of the divine twins Freyr and Freyja connects procreative masculine energy to both masculine abundance (Freyr) and feminine power (Freyja), suggesting the generative potential that emerges from balanced, nurturing masculinity.

Clinical Applications: The Njord pattern emerges in individuals who thrive in changing circumstances and derive prosperity from adaptability rather than control. In therapy, this presents as the capacity to navigate transitions with relative ease and to find opportunity in situations others might experience as threateningly unstable. Working with this pattern involves developing comfort with flux and change, particularly for those who seek excessive stability, while also respecting the legitimate needs of more stability-oriented aspects of the psyche (the Skadi elements). For individuals raised with limited models of masculinity, Njord offers an alternative pattern focused on nurturing provision rather than dominance or conquest.

Freyr

Mythological Background: God of fertility, prosperity, peace, and pleasure, Freyr was one of the Vanir deities, son of Njord and brother of Freyja. Associated with sunshine, fair weather, and bountiful harvests, he was widely worshipped, particularly by farmers. Freyr owned remarkable treasures: the ship Skíðblaðnir that could fold to pocket size yet hold all the gods, and the sword that fought by itself. He sacrificed this sword to win the giantess Gerð, whom he loved, which would leave him vulnerable at Ragnarök. Freyr was associated with the sacred boar Gullinbursti (“golden-bristled”), and in some traditions with the sacred kingship that ensured land fertility. His cult involved phallic symbols, and his statue at Uppsala was reportedly depicted with an enormous phallus. Unlike war gods, Freyr represented virility channeled into generativity rather than violence.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Skírnismál); Prose Edda; Gesta Danorum; Heimskringla; archaeological evidence from phallic figures and boar imagery.

Psychological Significance: Freyr embodies the archetype of masculine generativity that creates abundance through pleasure and peaceful relationship rather than through conquest or domination. His association with both agriculture and sexuality symbolizes the psychological connection between different forms of fertility—how creative energy manifests in multiple domains when allowed to flow naturally.

From a Jungian perspective, Freyr represents the animus in its generative rather than separative aspect—masculine energy that enhances and fertilizes rather than divides or conquers. His willingness to surrender his self-fighting sword for love symbolizes the psychological evolution from autonomous self-protection toward vulnerable engagement with the other, particularly with aspects of the unconscious (represented by the giantess Gerð from the realm of giants).

Freyr’s remarkable ship that can fold to pocket size yet expand to hold all the gods represents the psychological capacity for comprehensive containment that doesn’t require constant external display—the ability to carry tremendous potential in relatively inconspicuous form, expanding as needed to meet circumstances.

The golden boar associated with Freyr symbolizes the transformation of instinctual energy (the boar) into something valuable and radiant (gold) through conscious relationship with generative potential. Unlike the threatening boar of some traditions, Freyr’s boar serves as vehicle and companion, suggesting how instinctual energy can be channeled into service rather than requiring domination.

Clinical Applications: The Freyr pattern emerges in individuals who express masculine energy through generativity, abundance-creation, and pleasure rather than through competitiveness or dominance. In therapy, this presents as the capacity to surrender certain forms of power and autonomy to gain relational depth and creative partnership. Working with this pattern involves recognizing how legitimate vulnerabilities can serve growth rather than threaten it, while developing comfort with sensuality and pleasure as psychological resources rather than distractions or dangers. For individuals overly identified with aggressive or defensive expressions of masculinity, conscious engagement with Freyr-like qualities may offer healing alternatives.

The Norns

Mythological Background: The three Norns—Urðr (fate), Verðandi (becoming/present), and Skuld (debt/future)—were powerful female beings who shaped destiny by carving runes in the trunk of Yggdrasil, the world tree. Dwelling near the Well of Urðr beneath one of Yggdrasil’s roots, they watered the tree daily with the well’s water and white clay, preserving its vitality despite the constant gnawing of the serpent Níðhöggr at its roots. The Norns determined the fates of all beings, including the gods, and their judgments could not be altered, even by Odin. While the three main Norns shaped cosmic destiny, individual norns were said to attend each person’s birth to determine their fate. Unlike the Greek Fates, who spun, measured, and cut the thread of life, the Norse Norns carved fate directly into the living tissue of the world tree, suggesting fate as inscription rather than allotment.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá); Prose Edda; numerous references throughout Norse literature.

Psychological Significance: The Norns embody the archetype of destiny understood not as predetermined events but as the weaving together of past, present, and future into meaningful pattern. Their three-fold nature dramatizes how psychological experience integrates what has already occurred (Urðr), what is emerging (Verðandi), and what calls to us from ahead (Skuld).

From a Jungian perspective, the Norns represent the Self in its aspect as organizer of meaningful development over time. Their activity of carving runes into the world tree symbolizes how significant events inscribe themselves into the living tissue of psychological experience, creating patterns that shape future possibilities. Their daily watering of the tree with well water represents the psychological necessity of connecting developmental patterns to the depths of the unconscious (the well) to maintain vitality.

The Norns’ independence from even Odin’s authority suggests the psychological principle that certain developmental patterns transcend individual will, operating according to necessities inherent in the psyche itself. However, unlike rigid predestination, the Norns’ ongoing activity at the tree suggests destiny as continuous process rather than fixed blueprint.

The individual norns attending each birth represent how unique potential and limitation are present from the beginning of life, establishing parameters within which individual development unfolds. This suggests a psychological model that honors both inherent predisposition and ongoing development.

Clinical Applications: The Norns pattern emerges in experiences of recognizing meaningful connection between past, present, and future that transcends simple causality. In therapy, this presents as moments of insight regarding how apparently separate events form coherent patterns of development when viewed within larger temporal context. Working with this pattern involves helping clients shift from fragmented perception of life events toward recognition of meaningful developmental threads, while distinguishing between genuine pattern recognition and imposition of artificial meaning. For individuals struggling with apparent randomness or meaninglessness in their experience, engagement with the Norns perspective can provide containing recognition of purpose beyond immediate circumstances.

Valkyries

Mythological Background: Female warrior spirits who served Odin, the Valkyries (“choosers of the slain”) selected which warriors would die in battle and which would live. They escorted the chosen fallen to Valhalla, where these warriors would feast and train until Ragnarök, when they would fight alongside the gods. The Valkyries were typically depicted as armored maidens riding flying horses, sometimes accompanied by ravens and carrying spears or shields. While primarily death-spirits, certain Valkyries feature in heroic legends as lovers or wives to mortal heroes, such as Brynhildr in the Völsung cycle. These relationships typically end tragically due to the fundamental tension between the Valkyrie’s divine nature and the mortal hero’s limitations. In some sources, Valkyries also wove on looms threaded with human entrails, using severed heads as weights and arrows as shuttles, literally weaving the fabric of war’s outcome.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá, Grímnismál); Prose Edda; Njáls saga; various heroic poems and sagas, particularly those involving Sigurd/Siegfried.

Psychological Significance: The Valkyries embody the archetype of transformative feminine power that determines which aspects of identity survive developmental challenges and which must be sacrificed. Their selection of the slain dramatizes the psychological function that discriminates between what must be preserved and what must be surrendered during periods of conflict or crisis.

From a Jungian perspective, the Valkyries represent anima figures associated with the life-death-rebirth cycle rather than with nurturing or pleasure. Their warrior nature symbolizes how certain feminine psychological energies serve transformation through decisive selection and severance rather than through preservation or connection. The journey to Valhalla represents how psychological elements that “die” during developmental conflicts are not destroyed but transformed and preserved in altered form for future integration.

The tragic relationships between Valkyries and heroes in various legends symbolize the difficulty of integrating transformative feminine energy with mortal masculine consciousness. The hero who loves a Valkyrie seeks relationship with the transformative feminine but often cannot sustain this connection due to conventional limitations or expectations (often imposed by others).

The weaving Valkyries using human body parts on their looms represents the psychological truth that patterns of meaning emerge from literal embodied experience, particularly from encounters with limitation, suffering, and mortality. This grisly weaving suggests how transformative insight often requires direct engagement with life’s most difficult aspects rather than abstract contemplation.

Clinical Applications: The Valkyrie pattern emerges during psychological crises that require decisive discrimination between what must be preserved and what must be surrendered. In therapy, this presents as moments of necessary choice between competing values or identifications, particularly when maintaining all existing elements has become impossible. Working with this pattern involves developing capacity for clean severance when needed, recognizing how certain psychological elements may be transformed through apparent “death” rather than requiring preservation in current form. For individuals facing terminal illness or profound life transitions, the Valkyrie perspective offers dignified recognition of necessary endings without total destruction of meaning.

Fenrir

Mythological Background: One of three monstrous offspring of Loki and the giantess Angrboða, Fenrir was an enormous wolf who grew so rapidly and ferociously that the gods decided he must be bound. After two failed attempts with conventional fetters, they commissioned the dwarves to forge the unbreakable ribbon Gleipnir, made from impossible components (the sound of a cat’s footstep, the beard of a woman, the roots of a mountain, the sinews of a bear, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird). Suspecting trickery, Fenrir agreed to be bound only if one of the gods would place a hand in his mouth as pledge of good faith. Only Tyr was willing, knowing he would lose his hand when the deception was revealed. When Fenrir found himself truly trapped, he bit off Tyr’s hand but remained bound until Ragnarök, when he would break free, devour Odin, and subsequently be killed by Odin’s son Víðarr. In some traditions, Fenrir also swallows the sun during these final events.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá); Prose Edda; various archaeological contexts.

Psychological Significance: Fenrir embodies the archetype of instinctual power that grows too threatening to be integrated directly into existing consciousness and therefore must be contained through sacrifice and guile. His story dramatizes the psychological necessity of acknowledging, respecting, and binding certain primal energies that would otherwise overwhelm established structures.

From a Jungian perspective, Fenrir represents shadow elements that cannot be simply rejected or destroyed but must be recognized and contained without being allowed free expression. His binding through impossible materials (Gleipnir) symbolizes how certain psychological contents require paradoxical approaches that transcend conventional opposition—addressing what seems unmanageable through unexpected, seemingly impossible methods.

The necessity of Tyr’s sacrifice to bind Fenrir suggests how genuine containment of threatening unconscious elements requires consciousness to surrender something of value—how psychological integrity sometimes demands painful limitation of certain capacities to preserve larger wholeness.

Fenrir’s destined role at Ragnarök—devouring Odin but being slain by Víðarr—represents the psychological pattern of primal energies temporarily overwhelming established consciousness during profound transformation, yet ultimately being reintegrated in new form rather than permanently dominating the psyche.

Clinical Applications: The Fenrir pattern emerges when potentially overwhelming instinctual energies require acknowledgment and containment rather than either expression or repression. In therapy, this presents as the challenge of developing appropriate boundaries around powerful drives without either destructive acting out or rigid suppression. Working with this pattern involves recognizing which instinctual energies can be integrated directly and which require special containment measures, while accepting the sacrifices necessary for maintaining psychological integrity. For individuals struggling with addiction, rage, or other potentially overwhelming impulses, the Fenrir myth provides a template for respectful containment that neither demonizes nor surrenders to these energies.

Jormungandr

Mythological Background: One of Loki and Angrboða’s monstrous offspring, Jörmungandr (the Midgard Serpent) was a gigantic serpent thrown into the ocean by Odin, where it grew until it encircled the entire world, holding its own tail in its mouth. Thor encountered the serpent on multiple occasions, most famously during a fishing expedition with the giant Hymir, where Thor nearly pulled Jörmungandr from the sea using an ox head as bait. Hymir cut the line in fear, allowing the serpent to sink back into the depths. At Ragnarök, Jörmungandr would emerge from the ocean to battle Thor. Though Thor would kill the serpent, he would take only nine steps afterward before dying from its venom. The image of the world serpent has parallels in other Indo-European traditions and may represent both the encircling ocean and deeper conceptions of cosmic boundaries and cycles.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda; Prose Edda; various archaeological contexts, particularly representations of serpents biting their own tails.

Psychological Significance: Jörmungandr embodies the archetype of the ouroboros—the self-consuming serpent that simultaneously contains and delimits consciousness through its circular form. As world-encircler, it dramatizes the psychological boundary between known and unknown territories, between what consciousness can integrate and what remains beyond its current capacity.

From a Jungian perspective, Jörmungandr represents the unconscious in its aspect as both container and threat—the psychological forces that simultaneously provide necessary limitation for identity and threaten to dissolve established structures when directly encountered. Thor’s repeated confrontations with the serpent symbolize how heroic consciousness must periodically engage with these boundary forces without prematurely forcing their complete integration.

The serpent’s position in the depths of the ocean represents how these fundamental boundary-creating energies typically remain outside direct awareness, operating beneath the surface of conscious experience. Its emergence at Ragnarök symbolizes how profound psychological transformation necessarily involves direct confrontation with these boundary conditions, temporarily dissolving the distinction between what is “in” the psyche and what is “outside” it.

The mutual destruction of Thor and Jörmungandr at Ragnarök represents the psychological principle that certain transformative encounters necessarily change both consciousness and its boundaries—neither continues in its previous form, yet both serve the emergence of new psychological structures.

Clinical Applications: The Jörmungandr pattern emerges in experiences of engaging with fundamental boundaries of identity and meaning—confrontations with what contains current consciousness but also limits it. In therapy, this presents during major life transitions when existing psychological structures no longer adequately contain experience, requiring reconfiguration of basic boundaries. Working with this pattern involves respecting the necessary tension between heroic consciousness (Thor) and boundary conditions (the serpent), neither prematurely forcing confrontation nor avoiding necessary engagement. For individuals facing profound identity crises or spiritual emergencies, the mutual transformation of hero and serpent offers a template for understanding how both self and world-conception necessarily change through such encounters.

Yggdrasil

Mythological Background: The world tree Yggdrasil was an immense ash that connected and supported the nine realms of Norse cosmology. Its three main roots extended to the Well of Urðr (where the Norns dwelled), Jötunheimr (land of giants), and Niflheim (realm of primordial ice and mist containing Hvergelmir, source of many rivers). The tree suffered constant damage: the serpent Níðhöggr gnawed its roots, four stags devoured its foliage, and it was afflicted by rot, yet it remained ever-green through the Norns’ daily application of water and white clay from the Well of Urðr. Various beings inhabited the tree, including an eagle at its crown, a hawk between its eyes, a squirrel Ratatoskr who carried messages (often insulting) between the eagle and Níðhöggr, and numerous serpents at its roots. Odin hung himself from Yggdrasil for nine days and nights to gain knowledge of the runes, giving his eye to Mímir’s well beneath one of its roots for wisdom.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá, Grímnismál, Hávamál); Prose Edda; various symbolic representations in archaeological contexts.

Psychological Significance: Yggdrasil embodies the archetype of the axis mundi or world axis—the central organizing structure that connects different levels of experience while providing continuity through change. As the living container of reality, it dramatizes the psychological principle that meaningful experience requires both differentiated domains and connections between them.

From a Jungian perspective, Yggdrasil represents the Self in its aspect as organizing framework for the entire psyche—the living structure that maintains relationship between conscious and unconscious contents while providing continuity through developmental transformations. Its constant damage from various sources, alongside its perpetual renewal, symbolizes how psychological wholeness requires ongoing maintenance rather than representing a fixed, perfected state.

The different realms connected by Yggdrasil’s branches and roots symbolize the various domains of psychological experience—personal consciousness, personal unconscious, collective unconscious, archetypal dimensions, instinctual foundations, and transcendent potentials. Their connection through the tree represents how these apparently separate domains actually form an integrated system rather than truly separate territories.

Odin’s self-sacrifice on the tree to gain runic knowledge represents how certain forms of wisdom require voluntary surrender of existing perspectives (symbolized by the hanging) and willingness to perceive from depths usually avoided (symbolized by the sacrificed eye given to the well).

Clinical Applications: The Yggdrasil pattern emerges in experiences of perceiving meaningful connection between apparently disparate aspects of life—psychological, physical, social, and spiritual. In therapy, this presents as the development of a coherent self-narrative that integrates diverse experiences while maintaining differentiation between domains. Working with this pattern involves supporting both differentiation and integration, helping clients distinguish between psychological territories while recognizing their underlying connection. For individuals whose early experience lacked containing structure, developing an internal “world tree” that organizes experience without rigid categorization provides essential psychological resources for navigating complexity.

Mimir

Mythological Background: A mysterious figure associated with profound wisdom, Mímir (or Mím) was either an Aesir god or a giant who guarded a well beneath one of Yggdrasil’s roots containing waters of wisdom. Odin sacrificed one of his eyes to drink from this well, gaining greater understanding. During the Aesir-Vanir war, Mímir was sent as a hostage to the Vanir along with Hœnir. When the Vanir discovered that Hœnir gave wise counsel only when Mímir was present, they felt cheated and decapitated Mímir, sending his head to the Aesir. Odin preserved the head with herbs and spells, consulting it for secret knowledge and wisdom. In some accounts, Odin carried Mímir’s head with him, while in others it remained by its well, continuing to guard the waters of wisdom and speaking prophecies.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá); Prose Edda; Ynglinga saga.

Psychological Significance: Mímir embodies the archetype of disembodied wisdom—knowledge separated from ordinary vitality and function but preserved for its essential value. His well and severed-yet-speaking head dramatize the psychological principle that certain forms of insight require separation from ordinary consciousness to maintain their integrity and power.

From a Jungian perspective, Mímir represents the transpersonal wisdom function that exists somewhat independently from the ego yet remains accessible through appropriate “sacrifice” (symbolized by Odin’s eye). His well beneath Yggdrasil’s root symbolizes how this wisdom emerges from depths of the collective unconscious rather than from personal experience or conventional knowledge.

The preservation of Mímir’s head after decapitation represents the psychological pattern of maintaining connection with wisdom traditions or insights from the past that would otherwise be lost. The herbs and charms used by Odin to preserve the head symbolize how ritual, symbol, and conscious intention help maintain access to wisdom that might otherwise degrade through time or cultural change.

Mímir’s role in the Aesir-Vanir hostage exchange suggests the psychological challenge of integrating wisdom functions with practical action (represented by Hœnir). The Vanir’s anger at discovering Hœnir’s dependence on Mímir symbolizes the frustration that occurs when action and wisdom remain insufficiently integrated, operating as separate functions rather than unified process.

Clinical Applications: The Mímir pattern emerges in experiences of accessing wisdom that transcends personal knowledge or conventional understanding. In therapy, this presents as insights that seem to emerge from beyond the individual, connecting personal experience to transpersonal patterns and meanings. Working with this pattern involves developing appropriate “sacrifices” (disciplined attention, surrender of assumptions, dedicated contemplative practice) that facilitate access to wisdom sources beyond ego, while integrating these insights with practical action rather than maintaining them as separate, disembodied knowledge. For individuals navigating complex ethical decisions or seeking meaning beyond personal history, engagement with Mímir-like wisdom sources may provide essential guidance.

Idun

Mythological Background: Goddess of youth and renewal, Iðunn was keeper of the golden apples that preserved the gods’ immortality and vitality. Without these apples, the gods would age and weaken like mortals. In the most significant myth involving her, the giant Þjazi, in eagle form, forced Loki to lure Iðunn and her apples outside Asgard, whereupon Þjazi abducted her to his realm. As the gods began to age without the apples, they threatened Loki with torture and death unless he rescued her. Transforming into a falcon, Loki flew to Jötunheimr, changed Iðunn into a nut (or in some versions, a sparrow), and carried her back to Asgard. Þjazi pursued them in eagle form but was killed when he followed too closely to the walls of Asgard, where the gods had prepared a fire that burned his feathers, allowing them to slay him. Iðunn was wife to Bragi, god of poetry, and in some sources was said to house her apples in an ash box, possibly connecting her to the world tree Yggdrasil.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Lokasenna); Prose Edda (particularly Skáldskaparmál).

Psychological Significance: Iðunn embodies the archetype of renewal that preserves vitality through cyclical restoration rather than static permanence. Her golden apples dramatize the psychological resources that maintain enthusiasm, creativity, and engagement through life’s phases rather than allowing gradual depletion through time.

From a Jungian perspective, Iðunn represents the anima in its rejuvenating aspect—the feminine principle that reconnects masculine consciousness to its sources of vitality when routine and convention have depleted its energy. The theft of her apples by the giant Þjazi symbolizes how contact with these rejuvenating resources can be lost through the dominance of raw instinctual forces (represented by the giant in eagle form) that appropriate rather than relate to feminine energies.

The rapid aging of the gods without Iðunn’s apples represents the psychological staleness and rigid convention that develops when consciousness loses connection with its renewing sources. The necessity of Loki’s trickery to both lose and recover Iðunn suggests how the mercurial, boundary-crossing function serves both separation from and reconnection with these vital resources.

Iðunn’s marriage to Bragi, god of poetry, suggests the intimate connection between cyclical renewal and creative expression—how artistic and poetic functions depend on regular reconnection with rejuvenating psychological sources rather than merely technical skill.

Clinical Applications: The Iðunn pattern emerges in experiences of psychological renewal after periods of depletion, staleness, or convention-bound functioning. In therapy, this presents as rediscovery of enthusiasm, creativity, and vitality through reconnection with previously neglected psychological resources. Working with this pattern involves identifying what nourishes unique individual vitality, developing practices that maintain regular connection with these resources, and recognizing when vital energies have been “abducted” by instinctual forces requiring recalibration. For individuals experiencing burnout or loss of meaning in previously satisfying activities, the Iðunn perspective offers hope for renewal through reconnection rather than wholesale reinvention.

Bragi

Mythological Background: God of poetry, eloquence, and music, Bragi was renowned for his wisdom and verbal skill. Son of Odin in some accounts, he was husband to Iðunn, goddess of youth and renewal. Bragi was described as having runes carved on his tongue, symbolizing the magical power of poetic speech. As the divine poet, he entertained in Valhalla, greeting heroes upon their arrival with poetry honoring their deeds. The tradition of the bragarfull or “Bragi’s cup” involved making solemn vows over a consecrated drink at funerals and feasts, connecting oath-taking with poetic articulation. The term “bragr” in Old Norse refers to both poetry and the highest form of something, suggesting how poetic expression represented the pinnacle of cultural achievement. In some sources, Bragi appears as the deified form of the legendary human skald Bragi Boddason, potentially representing the transformation of human achievement into divine principle.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Lokasenna); Prose Edda; Sigrdrífumál.

Psychological Significance: Bragi embodies the archetype of articulate consciousness—the psychological function that transforms raw experience into meaningful expression. His rune-carved tongue dramatizes how this articulation involves both technical skill (knowledge of the runes as poetic conventions) and access to magical or numinous dimensions beyond ordinary speech.

From a Jungian perspective, Bragi represents the logos principle in its creative rather than merely analytical aspect—the capacity to bring forth new meaning through structured expression rather than simply describing what already exists. His marriage to Iðunn suggests how this articulating function depends on regular renewal from unconscious sources (Iðunn’s apples) rather than being self-sustaining through technical skill alone.

The tradition of the bragarfull or “Bragi’s cup” symbolizes how solemn commitment gains power through articulate expression rather than mere internal intention. This connection between speech, drink, and binding commitment represents the psychological principle that transformation requires bringing unconscious intent into formed expression to achieve lasting effect.

Bragi’s role greeting heroes in Valhalla with poetry honoring their deeds represents how narrative integration serves psychological completion—how experiences achieve their full meaning and value when articulated into coherent expression that can be shared with others.

Clinical Applications: The Bragi pattern emerges in the capacity to transform confusing or overwhelming experience into meaningful articulation. In therapy, this presents as the movement from inchoate feeling or fragmented perception toward coherent narrative and expressive voice. Working with this pattern involves developing both technical means of expression (vocabulary, narrative structure, metaphoric range) and openness to inspiration beyond conscious intention. For individuals who struggle to articulate their experience or who feel disconnected from creative expression, developing Bragi-like qualities may provide essential channels for psychological integration and shared meaning.

Skadi

Mythological Background: A giantess (jötunn) who became associated with the Aesir, Skadi was goddess of winter, mountains, skiing, hunting, and vengeance. After the gods killed her father Þjazi (when recovering Iðunn), Skadi came to Asgard armed for war, demanding compensation. The gods offered her three forms of redress: tears of gold from all the gods for her father, making her laugh despite her grief, and allowing her to choose a husband from among them, though she could see only their feet when choosing. Expecting to select the beautiful Baldr, she chose the feet that seemed most perfect, which belonged instead to Njord, god of the sea. Their marriage failed due to incompatible preferences—Skadi could not tolerate the cries of seabirds and brightness of the shore, while Njord could not endure the howling wolves and darkness of her mountain home. They separated amicably, each returning to their preferred environment. In some accounts, Skadi later married Odin and bore him sons, while in others she returned to her independent life as a huntress in the mountains.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda; Prose Edda; place names throughout Scandinavia.

Psychological Significance: Skadi embodies the archetype of the independent feminine that values clarity, solitude, and self-sufficiency over relationality or compromise. Her preference for the mountains over the seashore dramatizes the psychological orientation toward distinct boundaries and elevated perspective rather than fluidity and receptivity.

From a Jungian perspective, Skadi represents the anima in its autonomous, self-directed aspect—the feminine principle that maintains its essential nature rather than adapting to masculine expectations or needs. Her journey to Asgard seeking justice rather than approval symbolizes how this autonomous feminine consciousness addresses power structures directly rather than through indirect influence or accommodation.

The failed marriage with Njord, despite mutual respect, represents the psychological challenge of integrating fundamentally different orientations—the tension between clarity and boundary (Skadi’s mountains) and fluidity and communion (Njord’s seashore). Their amicable separation suggests the psychological wisdom of recognizing when certain internal elements function better with differentiation rather than forced integration.

Skadi’s compensation from the gods—gold tears, laughter, and husband-choice—symbolizes the multidimensional nature of psychological repair after injury: material acknowledgment, emotional release, and relational reconfiguration. That these forms of compensation ultimately prove insufficient for complete integration suggests the limitations of conventional reconciliation when addressing fundamental differences in orientation.

Clinical Applications: The Skadi pattern emerges in individuals who prioritize autonomy, clarity, and self-sufficiency, particularly women who define themselves outside conventional relational expectations. In therapy, this presents as the capacity for clear boundaries and independent purpose, sometimes accompanied by difficulty with extended intimacy or accommodating others’ different orientations. Working with this pattern involves honoring legitimate needs for autonomy and distinct territory while developing capacity for meaningful connection without essential compromise. For women socialized toward excessive accommodation, developing Skadi-like qualities may provide essential resources for psychological differentiation and authenticity.

Ran

Mythological Background: Goddess of the drowning sea, Rán was wife to Ægir (personification of the peaceful ocean) and mother of the nine wave-maidens. She possessed a net with which she caught sailors who fell into the sea, drawing them to her underwater hall. Unlike Hel, who received those who died of illness or old age, Rán specifically claimed those who perished in the treacherous depths. Sailors carried gold with them so they would be welcomed in her realm if they drowned. With Ægir, she hosted feasts for the gods in their underwater hall illuminated by glowing gold, using a cauldron obtained through Thor’s confrontation with the giant Hymir. While dangerous and feared, Rán was not considered malevolent but rather a necessary power who claimed what belonged to her domain and maintained appropriate boundaries between realms.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda; Prose Edda; Friðþjófs saga; various poetic references.

Psychological Significance: Rán embodies the archetype of dangerous receptivity—the feminine principle that draws consciousness into depths where ordinary functioning ceases but new potential may emerge. Her net dramatizes how certain psychological energies actively capture awareness rather than passively receiving it, creating immersion experiences that transcend ordinary boundaries.

From a Jungian perspective, Rán represents the unconscious in its actively claiming aspect—not merely waiting to be explored but reaching out to seize consciousness when it ventures into certain territories. The drowning she causes symbolizes the necessary surrender of ordinary ego functioning when engaging with particular unconscious depths, while the gold carried by sailors represents the valuables from conscious life that remain meaningful even in these transformative states.

The contrast between Rán and her husband Ægir suggests the psychological distinction between peaceful communion with the unconscious (Ægir’s calm seas and generous hospitality) and overwhelming immersion that suspends ordinary functioning (Rán’s drowning grasp). Their joint hosting of divine feasts represents how these complementary aspects of depth experience can serve heightened consciousness when properly contained.

Rán’s motherhood of the nine wave-maidens symbolizes how this immersive feminine principle generates multiple forms of transformative energy (the waves) that affect consciousness in diverse ways, from gentle influence to overwhelming power.

Clinical Applications: The Rán pattern emerges in experiences where consciousness is involuntarily drawn into psychological depths that suspend ordinary functioning. In therapy, this presents in overwhelming emotional states, captivating creative processes, or spiritual immersions that temporarily eclipse routine awareness. Working with this pattern involves developing capacity to surrender appropriately to these immersions while carrying “gold” (core values and identity elements) that maintains continuity through transformative encounters. For individuals who rigidly resist unconscious depths, recognizing the potentially generative nature of Rán-like experiences may reduce fear and facilitate necessary surrender, while those prone to drowning in overwhelming states may need strategies for maintaining essential continuity.

Sigyn

Mythological Background: Wife of Loki and goddess of fidelity and compassion, Sigyn is primarily known for her devotion during Loki’s punishment. After Loki engineered Baldr’s death and verbally attacked all the gods, he was bound with the entrails of his son Narfi (transformed into a wolf, who then killed his brother Váli), with a serpent positioned above to drip venom onto his face. Sigyn remained by her husband’s side, holding a bowl to catch the venom. When the bowl filled and she had to empty it, the venom would briefly touch Loki, causing him to writhe in agony—which was said to cause earthquakes. Despite Loki’s betrayal of the gods and the horrific nature of his punishment, Sigyn remained faithful to him, alleviating his suffering as much as possible without directly opposing the divine judgment.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá); Prose Edda.

Psychological Significance: Sigyn embodies the archetype of committed compassion that remains present with suffering without the power to completely eliminate it. Her bowl-holding dramatizes the psychological function that creates temporary relief within ongoing painful processes rather than escaping or resolving them entirely.

From a Jungian perspective, Sigyn represents the feminine principle in its aspect as witness and mitigator—the capacity to remain connected to what suffers without being overcome by it or having the power to transform it completely. Her unwavering presence with the bound and punished Loki symbolizes how certain forms of psychological healing come not through escape from painful consequences but through committed witnessing that eases without eliminating necessary suffering.

The inevitable moments when Sigyn must empty her bowl, allowing the venom to touch Loki, represent the psychological truth that even the most devoted caregiving includes necessary gaps—moments when pain must be directly experienced rather than shielded against.

Sigyn’s loyalty to Loki despite his crimes suggests how healthy psychological integration includes compassionate connection even to aspects of self that have caused harm or betrayal, without either rejecting them entirely or denying their genuine responsibility.

Clinical Applications: The Sigyn pattern emerges in situations requiring sustained compassionate presence with suffering that cannot be immediately resolved. In therapy, this presents as the capacity to witness pain without premature intervention, creating containment through presence rather than through solutions or escape. Working with this pattern involves developing the stamina for sustained compassionate attention, recognizing the value of mitigation rather than elimination of certain forms of suffering, and honoring the necessity of brief but inevitable moments when pain must be directly experienced. For caregivers at risk of burnout, the Sigyn myth provides important recognition of both the value and inherent limitations of compassionate witnessing.

Vidar

Mythological Background: Son of Odin and the giantess Gríðr, Víðarr was known as the silent god and one of the strongest of the Aesir. Though rarely mentioned in myths before Ragnarök, he played a crucial role in that final conflict. After Fenrir devoured Odin, Víðarr avenged his father by placing one foot on the wolf’s lower jaw (wearing a special shoe gathered from leather scraps people had saved) and pulling the upper jaw apart, killing the beast. Víðarr was one of the few gods destined to survive Ragnarök and participate in the renewal of the world afterward. His realm, Vidi, was described as a land of long grass and young saplings—images of growth and renewal.

Major Appearances: The Poetic Edda (particularly Völuspá and Vafþrúðnismál); Prose Edda.