-

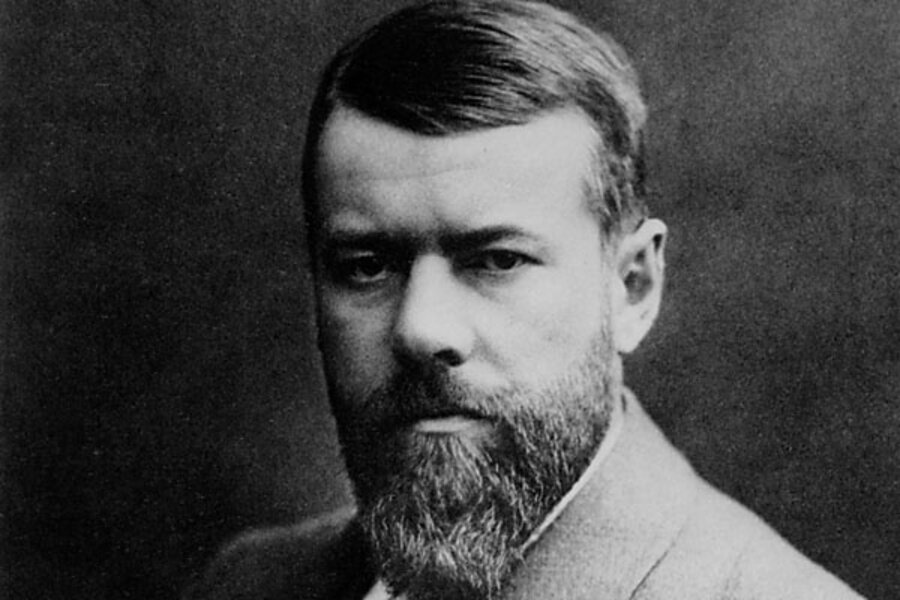

Who Was Max Webber?

Max Weber (1864-1920) stands as one of the founding fathers of modern sociology, alongside Émile Durkheim and Karl Marx. His groundbreaking work on social theory, religion, bureaucracy, and the nature of modernity has profoundly shaped our understanding of society and continues to influence social sciences today. Weber’s multifaceted approach to studying social phenomena, combining historical analysis with a keen understanding of economic and political structures, has provided invaluable insights into the complexities of modern life.

In this comprehensive essay, we will explore Weber’s key theoretical contributions, their impact on sociological thought, and their enduring relevance in the contemporary world. We will examine his concepts of social action, ideal types, and the Protestant work ethic, as well as his analyses of bureaucracy, rationalization, and the “iron cage” of modernity. By engaging with Weber’s ideas, we aim to shed light on the continuing significance of his work for understanding the structures and dynamics of modern society.

-

Weber’s Methodology and Approach to Social Science

2.1. Verstehen and Interpretive Sociology

Central to Weber’s approach to sociology is the concept of “Verstehen” (understanding), which emphasizes the importance of grasping the subjective meanings that individuals attach to their actions and experiences. Unlike the positivist approaches dominant in his time, Weber argued that social scientists must go beyond mere observation of external behaviors to comprehend the internal motivations and cultural contexts that shape human action.

This interpretive approach to sociology has had a profound influence on qualitative research methods and the development of symbolic interactionism, ethnomethodology, and other interpretive schools of thought in sociology. By emphasizing the role of meaning and interpretation in social life, Weber laid the groundwork for a more nuanced and culturally sensitive approach to studying human societies.

2.2. Ideal Types and Conceptual Analysis

Weber developed the concept of “ideal types” as a methodological tool for analyzing complex social phenomena. An ideal type is a conceptual construct that abstracts and synthesizes the essential features of a social phenomenon, serving as a benchmark against which empirical reality can be compared and understood. Examples of Weberian ideal types include bureaucracy, charismatic authority, and the Protestant ethic.

The use of ideal types has become a fundamental aspect of sociological analysis, allowing researchers to create theoretical models that capture the essential characteristics of social institutions, processes, and behaviors. This approach has been particularly influential in comparative historical sociology, organizational studies, and the analysis of social change.

2.3. Value-Free Social Science and the Fact-Value Distinction

Weber argued for a “value-free” approach to social science, maintaining that researchers should strive to separate their personal values and political beliefs from their scientific analyses. He emphasized the importance of distinguishing between empirical facts and value judgments, arguing that while values may guide the choice of research topics, they should not influence the conduct or interpretation of scientific inquiry.

This commitment to scientific objectivity and the fact-value distinction has been both influential and controversial in the development of sociology as a discipline. While many sociologists have embraced Weber’s call for methodological rigor and objectivity, others have criticized this approach as unrealistic or even undesirable, arguing for more explicitly value-oriented or critical forms of social research.

-

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

3.1. Religious Origins of Capitalist Values

In his seminal work “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” (1905), Weber proposed a novel explanation for the rise of modern capitalism in Western Europe and North America. He argued that the ascetic values and beliefs of certain Protestant denominations, particularly Calvinism, played a crucial role in fostering the attitudes and behaviors conducive to capitalist economic development.

According to Weber, the Calvinist doctrine of predestination led believers to seek signs of their salvation in worldly success, encouraging hard work, frugality, and reinvestment of profits. This “this-worldly asceticism” gradually evolved into a secular work ethic that continued to drive capitalist development even as religious motivations waned.

3.2. The Unintended Consequences of Religious Ideas

Weber’s analysis of the Protestant ethic highlights the importance of unintended consequences in social and historical processes. He argued that the religious reformers who promoted ascetic Protestantism had no intention of fostering capitalism; rather, their primary concern was the salvation of souls. Yet their teachings inadvertently contributed to the development of a new economic system and way of life.

This insight into the unintended consequences of social action has become a central theme in sociological analysis, encouraging researchers to look beyond the stated intentions of social actors to understand the broader and often unexpected impacts of their beliefs and behaviors.

3.3. The Cultural Foundations of Economic Systems

By linking religious ideas to economic behavior, Weber challenged the economic determinism of Marxist thought and highlighted the importance of cultural factors in shaping social and economic systems. His work demonstrated that economic structures are not solely determined by material conditions but are also influenced by cultural values, beliefs, and practices.

This cultural approach to understanding economic phenomena has had a lasting impact on economic sociology, development studies, and comparative analyses of economic systems. It has encouraged researchers to consider the complex interplay between cultural, social, and economic factors in shaping patterns of economic behavior and institutional development.

-

Rationalization and the “Iron Cage” of Modernity

4.1. The Process of Rationalization

Weber identified rationalization as a key feature of modern Western society, describing it as the increasing dominance of rational calculation, efficiency, and control in all spheres of life. This process involves the systematic organization of social life according to principles of efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control, often at the expense of traditional, emotional, or value-rational forms of action.

Weber argued that rationalization has profoundly shaped modern institutions, from bureaucratic organizations and legal systems to scientific research and technological development. While acknowledging the benefits of rationalization in terms of increased efficiency and productivity, Weber also warned of its potential negative consequences for human freedom and meaning.

4.2. Bureaucracy and Formal Organizations

Weber’s analysis of bureaucracy as the quintessential form of rational organization has been particularly influential in organizational sociology and public administration. He identified key features of bureaucratic organizations, including hierarchical structure, specialized roles, written rules and procedures, and impersonal relationships.

While recognizing the efficiency and effectiveness of bureaucratic organization, Weber also highlighted its potential drawbacks, including the dehumanization of social relationships, the stifling of creativity and innovation, and the concentration of power in the hands of technical experts and administrators.

4.3. The “Iron Cage” of Rationality

Weber famously described the outcome of the rationalization process as an “iron cage” (stahlhartes Gehäuse) in which individuals are increasingly trapped by systems of efficiency and control. He warned that the dominance of instrumental rationality in modern society could lead to a loss of meaning, freedom, and human agency, as individuals become mere “cogs in a machine” within large-scale bureaucratic systems.

This critique of modernity has had a profound impact on social theory and critical sociology, influencing thinkers such as the Frankfurt School theorists and contemporary critics of neoliberal capitalism. Weber’s concept of the “iron cage” continues to resonate with analyses of alienation, bureaucratization, and the commodification of social life in contemporary societies.

-

Authority, Power, and Legitimacy

5.1. Types of Legitimate Authority

Weber developed a influential typology of legitimate authority, distinguishing between three ideal types: traditional authority, based on long-established customs and traditions; charismatic authority, derived from the exceptional personal qualities of a leader; and legal-rational authority, grounded in formal rules and procedures.

This framework has been widely applied in political sociology, organizational studies, and leadership research, providing a nuanced understanding of the different bases of power and legitimacy in social systems. Weber’s analysis highlights the historical shift from traditional and charismatic forms of authority to the predominance of legal-rational authority in modern bureaucratic societies.

5.2. The Sociology of Politics and the State

Weber made significant contributions to political sociology, offering a comprehensive analysis of the modern state as a monopoly of legitimate violence within a given territory. He emphasized the importance of studying the actual functioning of political systems, rather than relying solely on formal constitutional arrangements or ideological claims.

His work on political parties, electoral systems, and the relationship between economics and politics has influenced generations of political sociologists and comparative politics scholars. Weber’s insights into the tension between bureaucratic administration and democratic accountability remain highly relevant to contemporary debates about governance and political representation.

5.3. The Ethics of Politics and the Vocation of Science

In his famous lectures “Politics as a Vocation” and “Science as a Vocation,” Weber explored the ethical challenges faced by individuals in political and scientific pursuits. He distinguished between an “ethic of ultimate ends” (Gesinnungsethik) and an “ethic of responsibility” (Verantwortungsethik), arguing that political leaders must balance their ideals with a pragmatic consideration of the consequences of their actions.

These reflections on the ethics of public life and the role of values in social science have had a lasting impact on discussions of political leadership, professional ethics, and the relationship between scholarship and social engagement.

-

Weber’s Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

6.1. The Continuing Influence of Weberian Sociology

Weber’s theoretical and methodological contributions continue to shape sociological research and theory across a wide range of subfields. His emphasis on multi-causal explanations, the importance of cultural factors, and the need for historically grounded analysis has influenced comparative-historical sociology, economic sociology, and the sociology of religion, among other areas.

Contemporary sociologists continue to draw on Weberian concepts and methods to analyze phenomena such as globalization, neoliberalism, religious fundamentalism, and the changing nature of work and organizations in the digital age.

6.2. Weber and the Challenges of Late Modernity

Many of the issues that concerned Weber at the turn of the 20th century remain highly relevant in the context of late modernity. His analyses of rationalization, bureaucratization, and the tension between efficiency and human values speak to ongoing debates about the impact of technology, the role of expertise in governance, and the challenges of maintaining democratic accountability in complex societies.

Weber’s work on the cultural foundations of economic behavior and the unintended consequences of social action provides valuable insights for understanding contemporary phenomena such as the global financial crisis, the rise of populist movements, and the cultural tensions associated with globalization.

6.3. Weber and Interdisciplinary Social Science

Weber’s interdisciplinary approach, combining insights from history, economics, political science, and cultural analysis, has been influential in promoting a more holistic and integrated approach to social research. His work has inspired scholars in fields such as historical sociology, political economy, and cultural studies to transcend disciplinary boundaries in pursuit of a more comprehensive understanding of social phenomena.

-

Lasting Relevance of Weber on Psychology

Max Weber’s contributions to sociology and social theory have left an indelible mark on our understanding of modern society. His nuanced analyses of rationalization, bureaucracy, authority, and the cultural foundations of economic behavior continue to provide valuable insights into the complexities of social life in the 21st century.

Weber’s methodological innovations, including the use of ideal types and the emphasis on interpretive understanding, have shaped the development of qualitative research methods and comparative analysis in the social sciences. His commitment to value-free social science, while controversial, has encouraged ongoing reflection on the relationship between facts and values in social research.

As we confront the challenges of late modernity, including the intensification of globalization, the transformation of work and organizations in the digital age, and the resurgence of populist and nationalist movements, Weber’s insights remain as relevant as ever. His warning about the potential for rationalization to create an “iron cage” of efficiency and control resonates with contemporary critiques of neoliberalism and technocratic governance.

By engaging with Weber’s ideas and building on his theoretical and methodological contributions, contemporary sociologists can continue to develop nuanced and historically grounded analyses of social phenomena. In doing so, they can honor Weber’s legacy while addressing the pressing social issues of our time.

-

Weber’s Key Works and Their Sociological Significance

8.1. “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” (1905)

This seminal work explores the relationship between religious ideas and economic behavior, challenging economic determinism and highlighting the importance of cultural factors in shaping social and economic systems.

8.2. “Economy and Society” (published posthumously in 1922)

This comprehensive treatise covers a wide range of sociological topics, including Weber’s theories of social action, authority, bureaucracy, and social stratification. It remains a foundational text in sociological theory.

8.3. “The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism” (1915)

This comparative study of Chinese religion and society demonstrates Weber’s approach to historical sociology and his interest in understanding the cultural foundations of different economic systems.

8.4. “Ancient Judaism” (1917-1919)

This work explores the development of ancient Jewish religion and its impact on Western rationalism, showcasing Weber’s approach to the sociology of religion and historical analysis.

8.5. “Politics as a Vocation” and “Science as a Vocation” (1919)

These influential lectures examine the ethical challenges faced by individuals in political and scientific pursuits, exploring themes of responsibility, values, and the nature of modern professions.

-

Bibliography

Aron, R. (1967). Main Currents in Sociological Thought: Durkheim, Pareto, Weber. Basic Books.

Bendix, R. (1960). Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait. Doubleday.

Collins, R. (1986). Weberian Sociological Theory. Cambridge University Press.

Gerth, H. H., & Mills, C. W. (Eds.). (1946). From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. Oxford University Press.

Kalberg, S. (1994). Max Weber’s Comparative-Historical Sociology. University of Chicago Press.

Mommsen, W. J. (1989). The Political and Social Theory of Max Weber: Collected Essays. University of Chicago Press.

Parsons, T. (1937). The Structure of Social Action. McGraw-Hill.

Roth, G., & Schluchter, W. (1979). Max Weber’s Vision of History: Ethics and Methods. University of California Press.

Scaff, L. A. (1989). Fleeing the Iron Cage: Culture, Politics, and Modernity in the Thought of Max Weber. University of California Press.

Schluchter, W. (1981). The Rise of Western Rationalism: Max Weber’s Developmental History. University of California Press.

Swedberg, R. (1998). Max Weber and the Idea of Economic Sociology. Princeton University Press.

Turner, B. S. (1981). For Weber: Essays on the Sociology of Fate. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Weber, M. (1949). The Methodology of the Social Sciences (E. A. Shils & H. A. Finch, Trans.). Free Press.

Weber, M. (1958). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (T. Parsons, Trans.). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Weber, M. (1968). Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). Bedminster Press.

Weber, M. (1994). Political Writings (P. Lassman & R. Speirs, Eds.). Cambridge University Press.

Whimster, S., & Lash, S. (Eds.). (1987). Max Weber, Rationality and Modernity. Allen & Unwin.

0 Comments