A New Paradigm for Understanding the Self

“The ultimate aim of the self is to be itself in relation to objects which are themselves.”

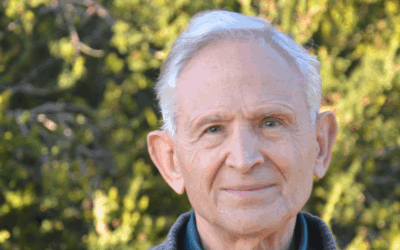

1. Who was Ronald Fairbairn

Ronald Fairbairn (1889-1964) was a Scottish psychoanalyst who played a pivotal role in the development of object relations theory. Diverging from classical Freudian drive theory, Fairbairn proposed a new model of the psyche centered on the individual’s relationships with real and internalized others. His innovative concepts of the endopsychic structure, the schizoid personality, and the moral defense revolutionized psychoanalytic thinking and paved the way for a more interpersonal and relational approach to therapy.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Fairbairn’s key ideas and their lasting impact on psychoanalytic theory and practice. It traces his intellectual journey, the central threads of his thought, and the ways he challenged and transformed the Freudian paradigm. It invites us to consider how Fairbairn’s insights can enrich our understanding of the self and its struggles in an increasingly interconnected world. I use Fairbains insights in therapy at Taproot Therapy Collective at my practice in Alabama.

Main Ideas

- Fairbairn rejected Freud’s drive theory, arguing that the psyche is fundamentally object-seeking rather than pleasure-seeking. Libido is not a biological drive but a function of the ego’s need for relationships.

- He proposed a new model of the endopsychic structure, composed of the central ego, the libidinal ego, and the antilibidinal ego. These structures are shaped by early object relationships and defensive splitting.

- Fairbairn saw psychopathology as rooted in failures of early dependency. When the infant’s needs for love and security are not met, it internalizes the rejecting parts of the object, leading to a basic schizoid split in the ego.

- He described the schizoid personality as the basic structure of psychopathology, characterized by a split between the self and others, and a retreat into an inner world of phantasy.

- Fairbairn emphasized the role of the moral defense in psychic life. The individual’s need to preserve the goodness of the object leads to a repression of bad object experiences and a split in the ego.

- He saw transference as a real relationship, not just a repetition of the past. The therapeutic relationship provides a new object experience that can help to heal early developmental failures.

- Fairbairn’s model implies a two-person psychology, where the self exists always in relation to others. This challenged the one-person model of classical theory and anticipated the relational turn in psychoanalysis.

- His ideas have been influential in the development of attachment theory, self psychology, and relational psychoanalysis. They continue to inspire new clinical and theoretical approaches today.

2. Biographical Context

Born in Edinburgh in 1889, Ronald Fairbairn grew up in a strict Calvinist household, the son of a Presbyterian minister. This early exposure to a religious worldview emphasizing sin, guilt, and the need for redemption would later inform his psychoanalytic theories, particularly his ideas on the moral defense and the splitting of the ego.

Fairbairn studied philosophy and divinity at Edinburgh University, but his interests soon turned to medicine and psychology. After serving in World War I, he completed his medical training and began working at the Gartnavel Royal Hospital in Glasgow, where he became interested in the treatment of schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders.

In the 1920s, Fairbairn underwent a personal analysis with E.H. Connell, a pioneer of psychoanalysis in Scotland. This experience introduced him to Freudian theory and sparked his lifelong fascination with the inner world of the psyche. He began applying psychoanalytic ideas to his work with schizophrenic patients, developing his own innovative techniques and theories in the process.

Fairbairn’s first major psychoanalytic publication, “Schizoid Factors in the Personality” (1940), laid out his critique of Freudian instinct theory and his alternative model of the endopsychic structure. He argued that schizoid tendencies – the splitting of the ego and the retreat into an inner world – were not limited to psychotic patients but were present to varying degrees in all individuals.

In 1941, Fairbairn was elected a member of the British Psychoanalytical Society, where he became a leading figure in the “Middle Group” of analysts who sought to integrate Kleinian and Freudian ideas. He served as president of the Scottish branch of the society from 1945 to 1947 and played a key role in establishing psychoanalysis as a respected profession in Britain.

Throughout the 1940s and 50s, Fairbairn continued to develop and refine his object relations theory, publishing seminal papers such as “A Revised Psychopathology of the Psychoses and Psychoneuroses” (1941), “The Repression and the Return of Bad Objects” (1943), and “Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality” (1952). These works challenged orthodox Freudian views and laid the groundwork for a new paradigm in psychoanalytic thinking.

Despite the originality and depth of his contributions, Fairbairn’s work was slow to gain recognition outside of Britain. His writing style was dense and difficult, and his ideas were often overshadowed by those of more prominent figures like Melanie Klein and Donald Winnicott. It was not until the 1970s and 80s that his theories began to receive wider attention, thanks in part to the efforts of his students and followers.

In recent decades, Fairbairn’s ideas have experienced a resurgence of interest among psychoanalysts, psychotherapists, and scholars across the humanities and social sciences. His emphasis on the primacy of object relations, the interpersonal matrix of the self, and the therapeutic power of the real relationship have struck a chord with contemporary sensibilities and concerns.

As we grapple with the challenges of an increasingly globalized and interconnected world, Fairbairn’s vision of the self as fundamentally embedded in social relations takes on new urgency and relevance. His work invites us to explore the complex interplay between our inner and outer worlds, and to envision new forms of healing and growth in the context of authentic human engagement.

3. Core Concepts

3.1 The Endopsychic Structure

At the heart of Fairbairn’s theory is his model of the endopsychic structure – the internal world of object relationships that shapes the individual’s sense of self and others. In contrast to Freud’s tripartite structure of id, ego, and superego, Fairbairn proposed a new topography of the psyche centered on three ego-structures: the central ego, the libidinal ego, and the anti-libidinal ego.

The central ego represents the core of the personality, the seat of conscious awareness and the agency of the self. It is the part of the psyche that engages with the external world and seeks to maintain relationships with real others. In healthy development, the central ego integrates and mediates between the other ego-structures, allowing for a fluid and flexible sense of self.

The libidinal ego is the part of the self that seeks connection and intimacy with others. It is the repository of good object experiences, the internalized sense of being loved and cared for. When development proceeds normally, the libidinal ego is integrated with the central ego, allowing the individual to form satisfying and reciprocal relationships.

The anti-libidinal ego, in contrast, is the part of the self that fears and defends against intimacy. It is the repository of bad object experiences, the internalized sense of being rejected or deprived. When development is disrupted by early failures of dependency, the anti-libidinal ego becomes split off from the central ego, leading to a basic schizoid division in the personality.

For Fairbairn, these ego-structures are not innate or biological, but are formed through the individual’s early experiences of object relations. In the first months of life, the infant is completely dependent on the mother for both physical and emotional sustenance. If the mother is consistently responsive and attuned to the infant’s needs, the infant internalizes a sense of being loved and valued, forming the basis for a secure and integrated sense of self.

However, if the mother is rejecting, inconsistent, or unable to meet the infant’s needs, the infant experiences a profound sense of deprivation and rage. Unable to tolerate these overwhelming negative feelings, the infant defensively splits them off from conscious awareness, projecting them onto the mother or other external objects. This splitting of the ego sets the stage for later psychopathology, as the individual continues to relate to others through the lens of these early unresolved conflicts.

Fairbairn’s model of the endopsychic structure thus offers a new way of understanding the formation of personality and the origins of emotional distress. It shifts the focus from innate drives and instincts to the dynamic interplay of internal objects and ego-structures. It suggests that our sense of self and others is not fixed or given, but is constantly being shaped and reshaped through our relationships and experiences.

At the same time, Fairbairn’s model also points to the transformative potential of the therapeutic relationship. By providing a new and corrective object experience, the therapist can help the individual to repair early developmental failures and to achieve a more integrated and authentic sense of self. This emphasis on the real relationship as a vehicle for change would become a hallmark of Fairbairn’s approach and a key influence on later relational and interpersonal theories.

3.2 The Schizoid Personality

Building on his model of the endopsychic structure, Fairbairn developed a groundbreaking theory of the schizoid personality as the basic prototype of psychopathology. He argued that schizoid tendencies – the splitting of the ego and the retreat into an inner world of fantasy – were not limited to psychotic patients, but were present to varying degrees in all individuals.

At the core of the schizoid personality is a fundamental split between the self and others, rooted in early experiences of deprivation and rejection. When the infant’s needs for love and security are not met, it defensively withdraws from the external world, creating an inner realm of imaginary objects and relationships. This retreat into fantasy allows the infant to maintain a sense of omnipotent control over its objects, but at the cost of genuine engagement with reality.

As development proceeds, this basic schizoid split becomes entrenched through the individual’s patterns of relating to self and others. The schizoid person adopts a “closed system” approach to relationships, avoiding dependency and vulnerability by maintaining a rigid boundary between inner and outer worlds. They may appear outwardly detached or self-sufficient, while secretly longing for intimacy and connection.

Fairbairn described several key features of the schizoid personality:

- Splitting of the ego: The schizoid person experiences a basic division between the “central ego” (the conscious self) and the “libidinal ego” (the unconscious self that longs for connection). This split allows them to maintain a facade of independence while disowning their own neediness and vulnerability.

- Schizoid object relations: The schizoid person relates to others as part-objects rather than whole persons. They may idealize or devalue others based on their ability to gratify specific needs, while failing to recognize their full humanity and complexity. This schizoid mode of relating perpetuates a cycle of disappointment and withdrawal.

- Schizoid fantasy: The schizoid person relies on fantasy and daydreaming as a way of coping with the pain of real relationships. They may create elaborate inner worlds populated by idealized or persecutory objects, while neglecting the challenges and rewards of external reality. This retreat into fantasy provides a sense of safety and control, but at the cost of genuine growth and development.

- Fear of engulfment: The schizoid person fears being overwhelmed or engulfed by others’ needs and demands. They may experience intimacy as a threat to their autonomy and sense of self, leading them to withdraw or lash out in self-protection. This fear of engulfment is rooted in early experiences of being invaded or controlled by powerful parental figures.

For Fairbairn, the schizoid personality represented a tragic failure of human potential – a state of arrested development in which the self remains trapped in a closed system of internal objects and fantasies. He saw the schizoid split as the root of all psychopathology, from the mild neuroses of everyday life to the severe fragmentations of psychosis.

At the same time, Fairbairn also recognized the creative and adaptive aspects of schizoid functioning. He noted that many artists, writers, and intellectuals display schizoid traits, using their rich inner lives as a source of inspiration and meaning. He also saw the schizoid person’s struggle for autonomy and self-definition as a universal human dilemma, reflecting the tension between our need for connection and our fear of being overwhelmed by others.

Fairbairn’s concept of the schizoid personality has had a profound impact on psychoanalytic theory and practice. It has shed light on the subtle ways in which we all defend against vulnerability and dependency, and the hidden costs of these defenses for our relationships and our sense of self. It has also pointed to the importance of early object relations in shaping personality development, and the need for a therapeutic approach that addresses these formative experiences.

In recent decades, Fairbairn’s ideas have been taken up and extended by a range of theorists and clinicians, from attachment researchers to relational psychoanalysts. His emphasis on the schizoid split as a basic structure of human experience has resonated with postmodern critiques of the unitary self, and with contemporary explorations of multiple self-states and dissociation.

As we navigate an increasingly fragmented and uncertain world, Fairbairn’s insights into the schizoid dilemma take on new relevance and urgency. They invite us to confront the ways in which we all retreat into fantasy and self-protection, and to envision new forms of connection and wholeness in the face of existential isolation. They challenge us to risk the vulnerability of real engagement, and to discover the transformative power of authentic human encounter.

3.3 The Moral Defense

One of Fairbairn’s most original and enduring contributions to psychoanalytic theory is his concept of the moral defense. He proposed that the individual’s need to preserve the goodness and integrity of the parental objects leads to a fundamental splitting of the ego, in which bad object experiences are repressed and separated from conscious awareness.

For Fairbairn, the moral defense is rooted in the infant’s absolute dependency on the mother for survival and emotional sustenance. In the face of inevitable frustrations and failures in this early relationship, the infant is confronted with a profound moral dilemma. On one hand, it experiences intense rage and aggression towards the mother for not meeting its needs. On the other hand, it cannot afford to fully acknowledge or express these negative feelings, for fear of losing the mother’s love and protection.

To resolve this dilemma, the infant unconsciously employs a defensive strategy of splitting and repression. It splits off the bad, frustrating aspects of the mother and internalizes them as part of its own ego-structure, while preserving the good, gratifying aspects as an idealized internal object. This allows the infant to maintain a sense of safety and goodness in its relationship with the mother, while taking on the burden of badness and aggression within its own self.

Over time, this basic pattern of moral defense becomes entrenched in the individual’s personality structure. The bad, rejected parts of the self are experienced as shameful and unacceptable, leading to feelings of guilt and inferiority. The good, idealized parts are experienced as unrealistic and unattainable, leading to a sense of longing and despair. The individual becomes caught in a cycle of self-blame and self-punishment, constantly striving to redeem the bad self in the eyes of the good object.

Fairbairn saw the moral defense as a universal feature of human development, arising from the inherent conflicts and power imbalances of the parent-child relationship. He argued that all individuals retain some degree of splitting and repression in their personality structure, even as they progress towards greater integration and wholeness.

At the same time, he recognized that the moral defense can become pathological when it is overused or rigidly maintained in later life. In such cases, the individual remains trapped in a closed system of internal objects, unable to engage fully with the challenges and rewards of external reality. They may experience a profound sense of inner emptiness and worthlessness, while presenting a facade of moral rectitude and self-sufficiency.

Fairbairn’s concept of the moral defense has had a significant impact on psychoanalytic understandings of guilt, shame, and the superego. It has shed light on the complex ways in which individuals internalize and perpetuate the conflicts and power dynamics of their early object relationships, and the lasting impact of these internalized structures on personality development.

In the clinical context, Fairbairn’s ideas have informed a therapeutic approach that seeks to identify and work through the individual’s moral defenses, allowing for a greater integration of split-off aspects of the self. By providing a new relational experience in which the patient can express and explore their authentic feelings and needs, the therapist can help to heal the basic schizoid split and restore a sense of wholeness and vitality.

Fairbairn’s emphasis on the moral dimension of psychic life has also resonated with contemporary concerns about the ethical and political implications of psychoanalytic practice. His ideas have been taken up by relational and feminist theorists, who have sought to challenge the power imbalances and cultural biases inherent in traditional models of the psyche. They have also been applied to the study of social and political processes, from the dynamics of oppression and resistance to the complex negotiations of identity and difference in a globalized world.

0 Comments