The Dream of Mathematical Prophecy

In Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, the mathematician Hari Seldon develops psychohistory—a mathematical sociology capable of predicting the future of large populations with statistical certainty. This fictional science, combining history, sociology, and mathematical statistics, represents humanity’s eternal desire to pierce the veil of time and glimpse our collective destiny. But what happens when this science fiction conceit begins to manifest in our contemporary world through big data, behavioral economics, and algorithmic prediction?

The concept of psychohistory emerges from a fundamental observation: while individual human behavior remains chaotic and unpredictable, large populations exhibit statistical regularities that can be modeled mathematically. This mirrors the principles of statistical mechanics in physics, where the random motion of individual gas molecules gives rise to predictable laws of thermodynamics at scale. The question that haunts us is not whether such predictions are possible, but whether we possess the courage to confront what they reveal about our trajectory.

The Visionaries Who Saw Beyond Their Time

Philip K. Dick stands as perhaps the most prescient of science fiction authors, not for his technological predictions but for his psychological insights into the nature of reality in a mediated society. Writing in the 1960s and 70s, Dick anticipated the crisis of authenticity that would define the digital age. His novels explored themes of simulated realities, corporate control of consciousness, and the dissolution of consensus reality—all before the internet existed. In works like “Ubik” and “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”, Dick portrayed worlds where the boundary between real and artificial, human and machine, authentic and simulated had become hopelessly blurred.

Dick’s paranoid visions weren’t merely literary devices but profound meditations on the trajectory of technological society. He understood that the primary battleground of the future would not be physical space but human consciousness itself. His concept of the “Black Iron Prison”—a metaphysical trap of false realities and control systems—prefigures our current predicament within algorithmic filter bubbles and manufactured consent.

The Media Theorists and Their Warnings

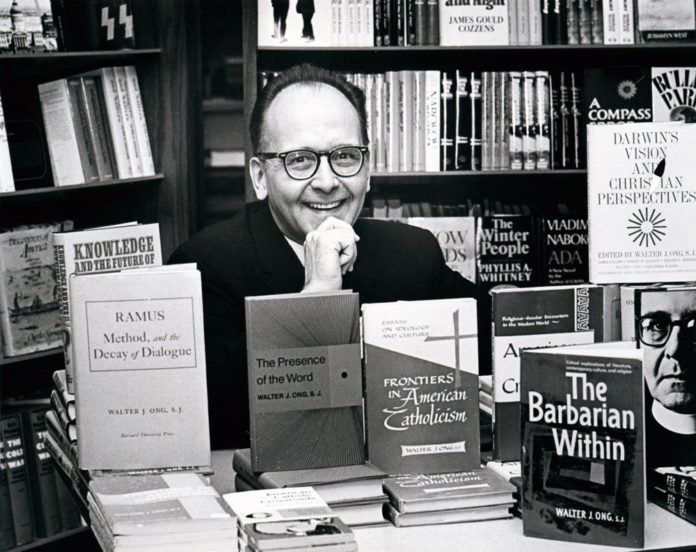

Marshall McLuhan’s declaration that “the medium is the message” revolutionized our understanding of how communication technologies reshape human consciousness and social organization. McLuhan saw that electronic media would create a “global village,” but he also warned of the retribalización and fragmentation this would entail. His insights into how media environments shape perception proved devastatingly accurate as social media platforms now demonstrably alter cognitive patterns and social behaviors.

Jean Baudrillard pushed these insights further with his theory of simulacra and simulation. For Baudrillard, we had entered a phase where simulations no longer referred to any underlying reality but had become self-referential systems generating their own hyperreality. The map had not only preceded the territory—it had replaced it entirely. His analysis of the Gulf War as a media spectacle that bore little relation to actual events on the ground presaged our current era of manufactured realities and competing narrative frameworks.

Guy Debord and the Situationists diagnosed modern capitalism as a “Society of the Spectacle” where authentic social life had been replaced by its representation. Debord’s insight that “all that was once directly lived has become mere representation” captures the essence of our social media age decades before its arrival. The Situationists understood that advanced capitalism wouldn’t merely exploit labor but would colonize consciousness itself, turning everyday life into a commodity to be consumed.

Vilém Flusser’s media philosophy explored how communication technologies fundamentally alter human consciousness and social relations. His concept of “technical images” as a new form of consciousness that would supersede linear writing proved remarkably prescient. Flusser saw that digital media would create new forms of magical thinking where images wouldn’t represent reality but would become programmatic instructions for creating it.

Edward Bernays, the “father of public relations” and Freud’s nephew, demonstrated how psychological insights could be weaponized for social control. His techniques for manufacturing consent laid the groundwork for modern propaganda and advertising. Bernays showed that democratic societies could be managed through the scientific manipulation of public opinion, turning psychology into a tool of governance.

Neil Postman’s warning that we were “amusing ourselves to death” through television culture seems almost quaint compared to our current digital predicament. Yet his core insight remains valid: that the logic of entertainment had colonized all forms of public discourse, making rational debate impossible. Postman understood that Huxley’s vision of control through pleasure was more insidious than Orwell’s vision of control through pain.

The Universe 25 Experiment and Social Collapse

John B. Calhoun’s Universe 25 experiment with mice populations in utopian conditions revealed disturbing patterns relevant to human societies. Despite unlimited food and absence of predators, the mouse colonies invariably collapsed into dysfunction and eventual extinction. The mice developed what Calhoun called a “behavioral sink”—a collection of pathological behaviors including withdrawal, aggression, and the cessation of normal reproductive behaviors.

The experiment’s phases mirror troubling aspects of advanced human societies: initial growth and prosperity followed by stagnation, social breakdown, and population collapse. The emergence of “the beautiful ones”—mice that withdrew from social interaction to focus solely on grooming and self-maintenance—eerily parallels contemporary phenomena of social withdrawal and narcissistic self-absorption in digital spaces.

The Mathematics of Inevitability

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver’s information theory provided the mathematical framework for understanding communication as a probabilistic system. Their work showed how information, entropy, and noise govern all communication systems, from telephone lines to human societies. This mathematical approach to information flow reveals constraints on social organization that no amount of technological progress can overcome.

Chaos theory and complexity science have shown us that while individual events remain unpredictable, system-level patterns exhibit remarkable regularities. The same power laws that govern earthquakes and forest fires also describe stock market crashes and social revolutions. These mathematical regularities suggest that certain civilizational patterns—cycles of integration and disintegration, periods of stability punctuated by rapid change—may be as inevitable as physical laws.

Network theory reveals how the structure of connections determines system behavior. As our societies become increasingly interconnected, they exhibit the properties of complex networks: small-world effects, scale-free distributions, and cascade failures. The mathematics tells us that highly connected systems are both more efficient and more fragile—a truth we’re discovering as global supply chains and information networks create unprecedented vulnerabilities.

What We Can Predict But Refuse to Accept

The mathematical models and historical patterns point toward several uncomfortable truths about our civilizational trajectory. Wealth concentration follows predictable power laws that, left unchecked, lead to social instability. The Gini coefficient’s steady rise across developed nations follows mathematical patterns seen before every major social upheaval in history.

Climate models, despite uncertainty in specifics, converge on catastrophic outcomes if current trends continue. The mathematics of exponential growth in resource consumption meeting finite planetary boundaries admits no escape through technological fixes alone. Yet we continue to organize our societies around growth imperatives that mathematics tells us are impossible to sustain.

The attention economy’s effects on human cognition follow predictable patterns of addiction and tolerance. The mathematics of variable ratio reinforcement—the same principles that make slot machines addictive—now govern social media engagement. We can predict with considerable accuracy the cognitive and social degradation this will produce, yet we continue to expose our children to these systems.

Demographic transitions in developed nations point toward population aging and decline that will fundamentally alter economic and social structures. The mathematics of pension systems and healthcare costs reveal looming crises that political systems seem incapable or unwilling to address. We know what’s coming but lack the political will to prepare.

The Lessons We Failed to Learn

Marcel Mauss’s study of gift economies revealed forms of social organization based on reciprocity rather than market exchange. Despite anthropological evidence of their stability and psychological benefits, we’ve largely abandoned these insights in favor of market fundamentalism. The gift economy persists in fragments—open source software, Wikipedia, mutual aid networks—but remains marginalized.

Erich Fromm’s analysis of the psychological roots of authoritarianism explained how freedom creates anxiety that drives people to seek escape in submission to authority. His warning about the “escape from freedom” predicted the appeal of authoritarian movements in democratic societies. Despite witnessing this pattern repeatedly, we fail to address the psychological conditions that create it.

The Left and Right Hand Path traditions in cultural psychology—representing different approaches to consciousness and social organization—offer insights into the dialectical nature of human development. The suppression of one path in favor of the other creates imbalances that eventually demand correction, often through violent upheaval. Yet we continue to ignore these cyclical patterns in favor of linear progress narratives.

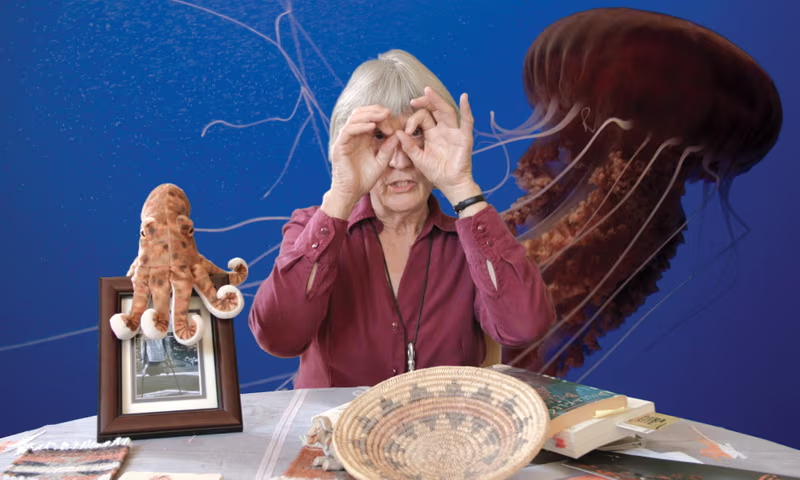

Donna Haraway’s cyborg feminism anticipated the breakdown of traditional boundaries between human and machine, nature and culture. Her insights into how technology reconstructs identity and social relations proved prescient, yet we stumbled into the digital age without seriously considering her warnings about the need for new forms of politics and ethics adequate to our hybrid reality.

Friedrich Kittler’s media archaeology revealed how communication technologies shape not just what we think but how we think. His insight that “media determine our situation” proves more relevant each day as algorithmic mediation shapes increasing portions of human experience. Yet we treat these transformations as merely technical rather than fundamentally existential.

Jung’s Thread and the Fragility of Civilization

Carl Jung’s observation that our psyche “hangs by a thread” captures the precarious nature of human consciousness balanced between order and chaos. Jung understood that civilization itself represents a thin veneer over primordial forces that modernity has not eliminated but merely repressed. The return of the repressed—in the form of mass movements, technological addictions, and meaning crises—suggests that thread is fraying.

Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious reveals how archetypal patterns persist beneath the surface of rational civilization. These patterns—the shadow, the trickster, the apocalypse—emerge with particular force during periods of rapid change. Our failure to consciously integrate these forces leaves us vulnerable to their autonomous eruption in destructive forms.

The individuation process Jung described—the integration of conscious and unconscious elements into a unified whole—applies not just to individuals but to civilizations. Our collective failure to undergo this process, to confront our shadow and integrate our projections, leaves us trapped in cycles of inflation and collapse.

The Limits of Prediction

Despite mathematical regularities and historical patterns, fundamental limits constrain our predictive abilities. Quantum mechanics reveals irreducible uncertainty at the foundation of reality. Gödel’s incompleteness theorems show that no formal system can be both complete and consistent. These mathematical limits suggest prophecy’s ultimate impossibility.

Human reflexivity—our ability to change behavior based on predictions—creates feedback loops that invalidate linear extrapolations. The very act of prediction alters what’s being predicted. This reflexive paradox means psychohistory must remain forever approximate, its predictions probabilistic rather than deterministic.

Black swan events—unpredictable occurrences with massive consequences—punctuate history in ways no model can anticipate. The emergence of the internet, the COVID-19 pandemic, the invention of nuclear weapons—these discontinuities reshape the landscape of possibility in ways that retrospectively seem inevitable but were prospectively invisible.

The Cold Equations of Civilizational Fate

The mathematics reveals patterns. The theorists provide frameworks. The experiments show outcomes. The science fiction authors imagine possibilities. Yet between knowledge and action falls the shadow of human nature—our cognitive biases, our social inertia, our existential anxiety.

We stand at an inflection point where the curves of technological acceleration, ecological degradation, social fragmentation, and cognitive overwhelm intersect. The mathematics suggests a phase transition approaching—a fundamental reorganization of human civilization whose specific form remains uncertain but whose inevitability grows clearer.

The thread holding our collective psyche may be fraying, but it has not yet snapped. In the gap between prediction and fate lies the space for human agency. Not the agency to prevent the inevitable, but to shape how we meet it. The choice is not whether to change but how to change—consciously or unconsciously, gracefully or catastrophically.

The equations are cold, but we need not be.

Bibliography

Asimov, Isaac. Foundation. Gnome Press, 1951.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. Horace Liveright, 1928.

Calhoun, John B. “Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 66, no. 1, 1973, pp. 80-88.

Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. Hamish Hamilton, 1955.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Zone Books, 1994.

Dick, Philip K. Ubik. Doubleday, 1969.

Flusser, Vilém. Into the Universe of Technical Images. University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Fromm, Erich. Escape from Freedom. Farrar & Rinehart, 1941.

Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge, 1991.

Jung, Carl. Man and His Symbols. Dell Publishing, 1964.

Kittler, Friedrich. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford University Press, 1999.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. MIT Press, 2001.

Mauss, Marcel. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. W.W. Norton, 1990.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Viking, 1985.

Shannon, Claude and Warren Weaver. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press, 1949.

0 Comments