The rockstar and prolific social worker Joanne Terrell at the University of Alabama once offered wisdom that continues to haunt the corridors of clinical practice: “If you ever think you’re right in ethics, you’re wrong.” Her words cut through the comfortable illusion that ethical practice follows clear guidelines, revealing instead that ethics exists perpetually in gray areas, where opposing forces pull practitioners toward incompatible conclusions. In the realm of psychotherapy, this tension has evolved into something more complex than traditional medical ethics ever anticipated, creating a three way conflict where patient care, insurance mandates, and liability concerns wage constant war over the soul of clinical practice.

Ethical Dilemmas in Therapy: Understanding the Three Masters

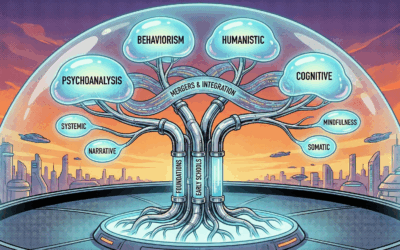

In an ideal world, psychotherapists would operate under a single ethical framework: medical ethics enforced by professional boards, centered on patient advocacy and personal autonomy. Social workers, psychologists, counselors, and other mental health professionals enter the field believing they will champion patient rights and facilitate healing. This noble vision represents the first master we serve, the ethical guidelines of our professional boards that prioritize patient welfare above all else.

Yet private practice reveals a more complicated reality. The moment a therapist opens their doors, they discover that patient centered ethics represents only one voice in many of competing demands. The introduction of insurance companies into mental health care has created a second master, one whose priorities often directly contradict those of traditional medical ethics. Insurance companies exist to generate profit, and their requirements for documentation, treatment justification, and compliance create an elaborate bureaucracy that fundamentally alters the therapeutic relationship.

Out of Network Therapists and State Insurance Laws

Many therapists believe they can escape this conflict by remaining out of network, accepting only cash payments and avoiding insurance entanglements altogether. This apparent solution, however, reveals a dangerous misunderstanding of contemporary healthcare law. Research into state regulations across the United States reveals a troubling reality: in states like California, New York, Texas, Florida, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, healthcare providers may still be bound by insurance regulations even when operating out of network.

State Laws for Out of Network Mental Health Providers

The regulatory landscape varies significantly across states, but common threads emerge that should concern every practicing therapist. In California, the Knox-Keene Health Care Service Plan Act and Health and Safety Code Section 1374.72 establish that any provider who might submit claims to an out of network insurance plan must comply with specific documentation and treatment standards. New York’s Insurance Law Article 49 creates similar obligations, while Texas Insurance Code Chapter 1301 extends insurance company oversight to any provider whose services might be reimbursed through out of network benefits.

Florida Statutes Title XXXVII, Chapter 627 mandates that mental health providers maintain records that meet insurance audit standards regardless of their network status. Illinois follows suit with the Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Code (405 ILCS 5/), which requires compliance with insurance documentation standards for any provider whose patients might seek reimbursement. Pennsylvania’s Act 68 and related regulations create a web of requirements that effectively bind all mental health providers to insurance standards if their patients have any form of health coverage.

These laws mean that the therapist who proudly declares independence from insurance networks while accepting cash from patients who submit superbills for out of network reimbursement may unknowingly violate state regulations. The penalties range from fines to loss of licensure, and ignorance of these requirements offers no defense.

Even more troubling, many therapists operating as “cash only” practices remain unaware they’re likely breaking the law. If your patient has any insurance whatsoever and might seek out of network reimbursement, you’re bound by insurance documentation standards in most states. That boutique practice charging $300 per session to avoid insurance hassles? They’re still legally required to maintain insurance compliant records. That therapist who markets themselves as “insurance free” to focus on pure clinical work? They’re one audit away from losing their license if their documentation doesn’t meet insurance standards they thought they’d escaped.

The best practice, of course, would be for these bureaucracies to get out of the way entirely and let the needs of patient care be the governing force. Insurance companies shouldn’t dictate clinical decisions. Lawyers shouldn’t drive treatment planning. Boards should trust clinical judgment. Unfortunately, this isn’t the world we live in. Instead, we operate in a system where profit motives, liability fears, and regulatory oversight have metastasized into a bureaucratic tumor that consumes more resources than actual patient care.

Professional Liability Insurance and Legal Risks in Therapy

The third master demanding allegiance is professional liability, a specter that haunts every clinical decision. While unethical or abusive providers deserve legal consequences and should make restitution for harm caused, the reality of modern practice means that even ethical, competent therapists face spurious lawsuits and harassment through legal channels. Professional liability insurance provides some protection, but avoiding court altogether remains the best practice rather than hoping to prevail once litigation begins.

This creates yet another layer of ethical complexity. Decisions that satisfy professional boards and insurance requirements may still leave therapists vulnerable to lawsuits. Conversely, actions taken to minimize liability exposure might violate board ethics or insurance regulations. The result is a constant triangulation where no decision fully satisfies all three masters.

The Impossible Task: Why You Can Never Do It “Right”

When therapists seek ethics consultation, they often arrive believing they “did it right.” They followed their board’s recommendations perfectly. Or they complied with every insurance mandate. Or they did exactly what their lawyer and professional liability insurance advised. The harsh reality that must be confronted is this: even if you guard against professional liability perfectly, you haven’t done it right, because you may have violated insurance requirements or board ethics. Even if you satisfy every insurance demand, you haven’t done it right, because you’ve likely increased liability exposure or violated ethical guidelines. Even if you follow board ethics to the letter, you haven’t done it right, because you’re now kicked out of insurance networks and facing lawsuits.

The problem is structural, not personal. Your policies for your clinic, your practice guidelines, your every interaction with patients must be governed by these three masters, and they are always pulling you in three different directions, all of the time. Not occasionally. Not in special circumstances. Always. Every progress note, every treatment plan, every clinical decision exists at the intersection of three incompatible value systems.

You may craft documentation that an insurance auditor loves, but it wouldn’t survive five minutes in court. You may develop policies your board praises as exemplary ethical practice, but they’ll get you sued by a patient’s family. You may implement risk management protocols that make your liability insurer ecstatic, but they’ll result in board sanctions for violating patient autonomy. There is no winning move, only strategic compromise.

When drafting policies, writing notes, or making clinical decisions, you must speak the language of all three realities simultaneously. This isn’t about finding balance or middle ground, because there often isn’t any. It’s about consciously choosing which master to disappoint in each specific situation while documenting your reasoning in language that minimizes damage from the other two. Every ethical decision in modern therapy practice involves calculating which failure mode is least destructive.

Common Ethical Conflicts in Mental Health Treatment

Documentation Requirements vs Patient Privacy

Insurance trends demand detailed documentation that often conflicts with patient privacy rights and therapeutic rapport. According to research published in the American Psychiatric Association’s guidelines on documentation, insurance audits require specific symptom descriptions, functional impairments, and treatment progress that patients may not want recorded in permanent files. Board ethics emphasize patient autonomy and minimal necessary documentation, while liability concerns push for exhaustive record keeping that could protect against future lawsuits.

Here’s the three way bind in action: A patient shares childhood sexual abuse details. Board ethics says document minimally to protect privacy. Insurance demands detailed trauma history to justify PTSD treatment. Liability insurance insists on comprehensive documentation to defend against potential “recovered memory” lawsuits. Whatever you write, you’re wrong by two of three standards.

Diagnosis Requirements and Treatment Planning Conflicts

Insurance reimbursement requires specific diagnoses from the DSM-5-TR, yet ethical practice sometimes calls for provisional or deferred diagnoses. The American Psychological Association’s ethical guidelines stress diagnostic accuracy and avoiding premature labeling, particularly with children and adolescents. However, insurance companies typically deny claims without definitive diagnoses submitted within the first few sessions. Meanwhile, liability concerns push therapists toward more severe diagnoses that justify intensive treatment, potentially stigmatizing patients unnecessarily.

Consider a college student with mild anxiety. Board ethics suggests avoiding pathologizing normal developmental stress. Insurance won’t pay without an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Liability concerns warn that under-diagnosing could lead to lawsuits if the student later harms themselves. You must choose which master to serve, knowing you’re failing the others.

Session Frequency and Duration Battles

Insurance companies increasingly limit session frequency and total authorized sessions, citing “medical necessity” criteria that often contradict clinical judgment and evidence based practice. The National Association of Social Workers’ practice standards emphasize treatment planning based on clinical assessment rather than arbitrary limits. Yet therapists who provide additional sessions risk insurance audits, recoupment demands, and fraud allegations. From a liability perspective, prematurely terminating treatment due to insurance limits could constitute patient abandonment.

A severely depressed patient needs twice weekly sessions. Insurance authorizes weekly only. Board ethics demands adequate treatment frequency. Liability standards require meeting the standard of care. Insurance threatens recoupment for unauthorized sessions. Providing needed care violates insurance rules. Following insurance rules violates ethical and liability standards. There is no right answer, only choosing which violation to commit.

The Suicide Contract Controversy: When Evidence Contradicts Legal Protection

Perhaps no example better illustrates the three way ethical bind than the use of suicide contracts or “no harm agreements.” Research consistently demonstrates their clinical ineffectiveness. A comprehensive review in the British Journal of Psychiatry found no evidence that suicide contracts reduce suicide risk and suggested they might actually increase risk by creating false security or damaging therapeutic alliance when patients feel coerced.

Professional boards generally discourage their use, recognizing the lack of empirical support. The American Association of Suicidology’s position statement explicitly states that no-suicide contracts should not replace comprehensive risk assessment and evidence based interventions. Insurance companies remain largely neutral, neither requiring nor prohibiting their use.

Yet from a liability perspective, suicide contracts persist because they demonstrate “due diligence” in court. When defending against wrongful death lawsuits, attorneys argue that contracts show the therapist took suicide risk seriously and attempted intervention. Some facilities and practices mandate their use specifically for legal protection, forcing clinicians to choose between evidence based practice and liability reduction.

Informed Consent Complications in Modern Practice

The informed consent process has evolved into a minefield where satisfying one master inevitably disappoints others. Board ethics require clear, understandable consent focused on patient rights and treatment risks. Insurance companies demand specific language about coverage limitations, authorization requirements, and financial responsibilities. Liability concerns push for exhaustive documentation of every possible risk, creating consent forms so lengthy and complex that meaningful informed consent becomes impossible.

Consider telehealth consent requirements that exploded during the COVID-19 pandemic. State boards require basic consent for remote services. Insurance companies add requirements about technology platforms, interstate practice limitations, and emergency protocols. Liability insurers insist on documentation about technical failures, privacy limitations, and jurisdictional complexities. The resulting consent process can consume entire sessions, ironically reducing time for actual therapeutic intervention.

HIPAA vs Insurance Audits: The Privacy Paradox

HIPAA regulations ostensibly protect patient privacy, yet insurance audits routinely demand access to complete clinical records. The Department of Health and Human Services’ minimum necessary standard conflicts with insurance companies’ audit requirements for comprehensive documentation. Therapists face an impossible choice: provide minimal information and risk claim denials and network expulsion, or share detailed records and potentially violate patient privacy rights.

The situation worsens when patients request record restrictions under HIPAA while using insurance benefits. Technically, patients can request that certain information not be shared with insurers, but doing so may result in claim denials and retroactive billing. Therapists must navigate between honoring patient preferences, maintaining insurance compliance, and avoiding fraud allegations.

Treatment Termination: Abandonment vs Financial Reality

Ending treatment presents another ethical minefield. Board ethics prohibit patient abandonment and require appropriate termination procedures with referrals. Insurance companies may abruptly terminate authorization, forcing immediate treatment cessation. Liability concerns arise from both premature termination (abandonment claims) and extended treatment (dependency fostering allegations).

When patients lose insurance coverage mid-treatment, therapists face wrenching decisions. Continuing pro bono treatment may be financially unsustainable and create liability issues around standard of care. Immediate termination could constitute abandonment. Reduced fee arrangements might violate insurance contracts if the patient later regains coverage. Each option carries risks across all three domains.

Mandatory Reporting and Confidentiality Conflicts

Mandatory reporting requirements create some of the most acute ethical tensions. State boards establish reporting requirements for child abuse, elder abuse, and imminent danger. Insurance companies may require different reporting thresholds or additional notifications. Liability concerns push both toward over-reporting (avoiding failure to report lawsuits) and under-reporting (maintaining therapeutic alliance and avoiding defamation claims).

The complexity multiplies when dealing with adolescent patients. Some states grant minors consent capacity for mental health treatment while requiring parental involvement for insurance billing. The Guttmacher Institute’s research on minor consent laws reveals a patchwork of conflicting requirements that leave therapists vulnerable regardless of their choices.

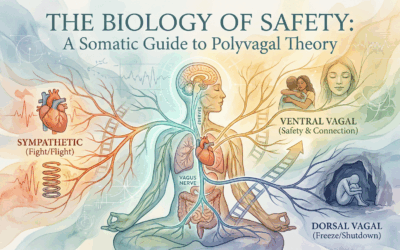

Crisis Intervention: Safety vs Autonomy vs Coverage

Crisis situations crystallize the three way bind. Board ethics emphasize least restrictive interventions and patient autonomy. Insurance companies may require specific protocols or refuse coverage for certain interventions. Liability concerns push toward conservative approaches and hospitalization to avoid wrongful death suits.

Consider a patient expressing suicidal ideation without clear intent or plan. Ethical practice might support continued outpatient treatment with increased monitoring. Insurance might deny coverage for increased session frequency. Liability concerns favor hospitalization despite its potential trauma and disruption. No choice fully satisfies all three masters.

Best Practices for Navigating Ethical Conflicts in Therapy

Developing Comprehensive Practice Policies

Creating robust practice policies requires speaking the language of all three masters simultaneously. This is not optional. Every policy statement, every consent form, every clinical protocol must be written with awareness of how it will be read by an insurance auditor, a plaintiff’s attorney, and a board investigator. A single paragraph often needs three different phrasings woven together: medical necessity language for insurance, risk acknowledgment for liability, and patient empowerment language for ethics.

Consider a simple informed consent statement about treatment risks. Your board wants clear, honest communication about potential negative outcomes. Insurance wants documentation that treatment is medically necessary despite risks. Liability counsel wants exhaustive listing of every conceivable risk to prevent “failure to warn” lawsuits. The resulting document becomes a Frankenstein’s monster of competing agendas, where clarity dies in service of comprehensive coverage.

Start by conducting a thorough review of your state’s regulations, your insurance contracts, and your professional board’s ethical guidelines. Map areas of conflict and develop specific protocols for common scenarios. But here’s the critical part: accept that your policies will always be wrong by someone’s standards. The goal isn’t to satisfy all three masters, which is impossible, but to fail each one strategically in ways that minimize overall risk.

The Three Languages You Must Master

Insurance Language: Learn to frame clinical decisions in terms of medical necessity, functional impairment, and measurable outcomes. Every intervention must be justified as the least costly effective treatment. Progress must be quantifiable. Setbacks must be explained as complications requiring continued treatment, not therapeutic impasses.

Liability Language: Master the art of defensive documentation that demonstrates reasonable professional judgment. Every decision needs a risk-benefit analysis. Every unusual intervention requires informed consent documentation. Every termination needs careful transition planning. Write as if a hostile attorney will scrutinize every word.

Ethics Language: Maintain focus on patient autonomy, collaborative treatment planning, and minimal necessary intervention. Document shared decision making, respect for patient values, and commitment to beneficence. Frame treatments as empowering patient choice even when insurance or liability concerns actually drive decisions.

The skillful practitioner learns to write single sentences that speak all three languages simultaneously. For example: “After discussing treatment options including risks and benefits (liability), the patient chose to continue weekly therapy to address functional impairments in work performance (insurance) through a collaborative approach respecting their stated treatment goals (ethics).”

Creating Ethical Decision Making Frameworks

Develop a systematic approach to ethical dilemmas that acknowledges all three competing demands. When facing difficult decisions, document how each option affects board compliance, insurance requirements, and liability exposure. This documentation itself serves multiple purposes: demonstrating ethical deliberation for board reviews, showing good faith effort for insurance appeals, and establishing reasonable professional judgment for liability defense.

Consider establishing an ethics consultation group with colleagues who understand the three way bind. Regular case consultation provides peer support, diverse perspectives, and documentation of professional deliberation. Some liability insurers offer premium discounts for participation in peer consultation groups, recognizing their value in risk reduction.

Documentation Strategies That Serve All Masters

Master the art of strategic documentation that satisfies multiple requirements without compromising therapeutic work. Develop templates that capture insurance required elements while maintaining clinical focus. Use precise language that meets legal standards without pathologizing patients unnecessarily. Create separate sections for different audiences: clinical notes for treatment purposes, administrative notes for insurance requirements, and risk management documentation for liability protection.

Learn to write progress notes that tell different stories to different readers. Insurance auditors see medical necessity and treatment progress. Board reviewers see ethical practice and patient centered care. Attorneys see risk assessment and professional judgment. The same note can satisfy all three when crafted skillfully.

Insurance Navigation and Appeals Processes

Become expert in insurance appeals and grievance processes. When insurance requirements conflict with clinical judgment or ethical obligations, document the conflict and appeal denials systematically. Successful appeals create precedents that protect both individual patients and future practice. Failed appeals document good faith efforts that may protect against board complaints or liability claims.

Develop relationships with insurance case managers and medical directors. Understanding their pressures and constraints enables more effective advocacy. Sometimes reframing clinical needs in insurance language achieves coverage without compromising care. Other times, documenting insurance barriers protects against abandonment allegations when treatment must end.

Risk Management Without Compromising Care

Implement risk management strategies that enhance rather than obstruct therapeutic work. Instead of defensive practice that prioritizes liability protection over patient care, develop approaches that achieve both. Comprehensive assessment protocols can identify risks while building therapeutic alliance. Safety planning can replace problematic suicide contracts while providing better clinical intervention and legal documentation.

Invest in ongoing training that addresses all three domains. Clinical training improves patient care and satisfies board requirements. Insurance compliance training reduces audit risks and claim denials. Risk management training minimizes liability exposure. Integrated training that addresses all three simultaneously proves most valuable.

Building Collaborative Professional Networks

Cultivate relationships with professionals who understand the three way bind. Develop referral networks with colleagues who navigate similar challenges. Establish connections with attorneys who understand mental health practice, insurance representatives who respect clinical judgment, and board members who recognize real world constraints.

Consider joining professional organizations that advocate for realistic integration of competing demands. The National Association of Social Workers, American Counseling Association, and similar organizations work to influence policy across all three domains. Their practice guidelines and advocacy efforts help reconcile conflicting requirements.

Training and Supervision Considerations

For those training new therapists or providing supervision, explicitly address the three way bind rather than pretending it doesn’t exist. Traditional training often emphasizes ideal practice without acknowledging real world constraints. Supervisees need preparation for the ethical complexity they’ll face, including strategies for managing competing demands without burning out or becoming cynical.

Develop supervision models that examine cases through all three lenses. Help supervisees understand that feeling pulled in multiple directions reflects systemic problems rather than personal inadequacy. Teach them to document their reasoning when forced to choose between competing goods, all of which serve important purposes.

The Human Cost of Ethical Conflicts in Therapy

The three way bind extracts a significant toll on mental health providers. Moral distress from constantly choosing between competing ethical demands contributes to burnout, secondary trauma, and professional exodus. Therapists report feeling like they’re failing someone regardless of their choices: patients, insurers, boards, or themselves.

This systemic dysfunction affects patient care quality. Time spent navigating competing requirements reduces therapeutic availability. Energy depleted by administrative battles diminishes clinical presence. Defensive practice born from liability fears constrains therapeutic creativity. The profession loses experienced practitioners who refuse to continue fighting unwinnable battles.

Systemic Reform: Imagining Ethical Alignment

While individual practitioners must navigate current realities, systemic reform remains essential. Advocacy efforts should focus on aligning the three masters rather than accepting their perpetual conflict. This means pushing for insurance regulations that respect clinical judgment, liability standards that recognize good faith clinical effort, and board ethics that acknowledge practical constraints.

Some states have begun experimenting with integrated approaches. Vermont’s mental health parity enforcement includes provisions protecting clinical judgment. Oregon’s coordinated care organizations attempt to align financial incentives with patient outcomes. These experiments suggest possibilities for reducing the three way bind through systemic reform rather than individual accommodation.

Technology and Future Ethical Challenges

Emerging technologies add new dimensions to existing ethical conflicts. Artificial intelligence therapy tools raise questions about liability for algorithmic decisions. Digital therapeutics blur boundaries between medical devices and psychological interventions. Telehealth platforms create jurisdictional complexities that multiply regulatory requirements.

Each technological advance potentially offers solutions while creating new problems. Electronic health records could streamline documentation for all three masters but raise privacy concerns. Outcome measurement tools could demonstrate treatment effectiveness but risk reducing therapy to metrics. Therapists must evaluate new technologies through all three lenses, adopting those that serve multiple masters while avoiding those that exacerbate conflicts.

Conclusion: Embracing Ethical Complexity in Mental Health Practice

Joanne Terrell’s wisdom about ethical gray areas proves more prescient with each passing year. “If you ever think you’re right in ethics, you’re wrong,” she taught, because ethics is always a push and pull between opposing forces, and there’s never an easy answer. In modern psychotherapy practice, this truth has evolved into something even more complex: not just gray areas between right and wrong, but a perpetual state of being wrong by at least two out of three essential standards.

The fantasy of doing ethics “right” dissolves when facing the reality of three masters with incompatible demands. You cannot satisfy your board, insurance companies, and liability concerns simultaneously. This is not a skills deficit or knowledge gap that more training will fix. It’s the fundamental structure of American mental health care. Every single decision you make as a therapist will violate at least one, usually two, of these three frameworks.

Excellence in modern psychotherapy requires not moral purity but skillful triangulation. The best practitioners accept that they will always be failing someone’s standards. They learn to speak multiple languages simultaneously, crafting interventions that serve patients while strategically choosing which violations to commit. They document not to prove they did it right, but to show they thoughtfully chose which way to do it wrong. They appeal systematically, advocate persistently, and most importantly, maintain clarity about their primary commitment to patient welfare while acknowledging that even this commitment requires constant compromise.

When you find yourself pulled in three directions, remember: this isn’t a problem to be solved but the permanent condition of ethical practice. The therapist who claims they’ve found a way to satisfy all three masters is either lying or dangerously naive. The ethical therapist accepts this reality not as defeat but as the complex terrain of contemporary practice. In the gray areas where insurance mandates clash with clinical judgment, where liability concerns conflict with therapeutic risk taking, and where board ethics meet market realities, dedicated professionals continue finding ways to serve their patients not despite the impossibility of doing it right, but through the conscious choice of how to do it wrong in the least harmful way.

The work remains possible, even necessary, precisely because it is difficult. Each therapist who successfully navigates these competing demands creates small spaces where healing occurs despite systemic dysfunction. These spaces exist not because we’ve solved the three way bind, but because we’ve learned to dance within it, always pulled in three directions, never doing it right, but doing it anyway with as much integrity as the broken system allows.

0 Comments