Who was Simone Weil?

Simone Weil, the French philosopher, mystic, and political activist, left an indelible mark on 20th-century thought through her profound and often paradoxical reflections on the human condition. Born in 1909 to a wealthy Jewish family in Paris, Weil was a precocious child who excelled academically and developed a deep concern for social justice at an early age. Despite her privileged background, she chose to live a life of voluntary poverty and solidarity with the oppressed, working in factories, participating in the Spanish Civil War, and ultimately seeking spiritual truth through a unique form of Christian mysticism. While her life was cut short by illness at the age of 34, Weil’s writings continue to inspire and challenge readers with their penetrating insights into the nature of suffering, the search for meaning, and the possibility of transcendence. Central to her philosophy was a deep grappling with the contradictions and mysteries of existence, which she sought to illuminate through a masterful use of metaphor, simile, and paradox. These rhetorical devices were not merely stylistic flourishes, but essential tools for conveying the depth and complexity of her spiritual and political vision. By exploring Weil’s use of these literary techniques, we can gain a deeper appreciation for her unique contributions to the fields of philosophy, theology, and psychology, and find new ways to apply her insights to the challenges of our own time.

Simone Weil, the French philosopher, mystic, and political activist, left an indelible mark on 20th-century thought through her profound and often paradoxical reflections on the human condition. Born in 1909 to a wealthy Jewish family in Paris, Weil was a precocious child who excelled academically and developed a deep concern for social justice at an early age. Despite her privileged background, she chose to live a life of voluntary poverty and solidarity with the oppressed, working in factories, participating in the Spanish Civil War, and ultimately seeking spiritual truth through a unique form of Christian mysticism. While her life was cut short by illness at the age of 34, Weil’s writings continue to inspire and challenge readers with their penetrating insights into the nature of suffering, the search for meaning, and the possibility of transcendence. Central to her philosophy was a deep grappling with the contradictions and mysteries of existence, which she sought to illuminate through a masterful use of metaphor, simile, and paradox. These rhetorical devices were not merely stylistic flourishes, but essential tools for conveying the depth and complexity of her spiritual and political vision. By exploring Weil’s use of these literary techniques, we can gain a deeper appreciation for her unique contributions to the fields of philosophy, theology, and psychology, and find new ways to apply her insights to the challenges of our own time.

The Roots of Weil’s Mysticism

Weil’s spiritual journey was shaped by a wide range of influences, from ancient Greek philosophy to Christian mysticism, Buddhism, and Hinduism. She was particularly drawn to the concept of “affliction,” which she saw as a state of physical and psychological suffering that stripped away the illusions of the self and opened the way for a direct encounter with the divine. For Weil, suffering was not merely something to be avoided or overcome but a potential gateway to spiritual transformation and union with God. At the same time, Weil’s mysticism was deeply grounded in a concern for social justice and a critique of oppressive power structures. She believed that the suffering of the oppressed and marginalized was a direct manifestation of the brokenness of the world and that true spirituality required a commitment to alleviating this suffering through concrete political action.

Weil’s Philosophy and Its Implications

Central to Weil’s thought was the idea of “decreation,” a process of stripping away the false self in order to make room for the divine. She believed that the ego, with its attachments and desires, was the primary obstacle to spiritual growth and that true freedom could only be found through a radical renunciation of the self. This idea has profound implications for psychology and the understanding of human development, challenging dominant notions of individuality and self-actualization. At the same time, Weil’s philosophy emphasized the importance of attention and receptivity in the face of suffering and injustice. She believed that the ability to truly see and attend to the reality of others’ pain was a prerequisite for genuine compassion and solidarity. This idea has important applications in fields such as psychotherapy and social work, suggesting the need for a kind of radical empathy that goes beyond mere sympathy or pity.

Central to Weil’s thought was her dialectical approach, which sought to reconcile seemingly opposing ideas and experiences. She was deeply influenced by Platonic philosophy, with its emphasis on the transcendent realm of ideas, while also drawing on Christian theology and her own experiences of physical and emotional pain. Weil’s writing style reflects this dialectical tension, as she grapples with the paradoxes and contradictions of human existence, seeking to find unity and meaning in the midst of suffering and despair. One of the key focal points of Weil’s philosophy was the concept of affliction, which she saw as a profound form of suffering that encompassed physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions. For Weil, affliction was not merely an individual experience but a reflection of the brokenness and injustice of the world. She believed that by embracing and understanding affliction, one could begin to access a deeper level of spiritual truth and compassion.

Weil’s Relevance for Contemporary Psychology and Spirituality

While Weil’s ideas were rooted in a specific historical and cultural context, her insights into the nature of suffering, the self, and the search for meaning continue to resonate with contemporary audiences. Her vision of a spirituality that is grounded in compassion, social justice, and the embrace of affliction offers a powerful challenge to dominant paradigms of individualism and self-fulfillment. For those struggling with psychological distress or existential despair, Weil’s writings offer a unique perspective on the transformative potential of suffering and the possibility of finding meaning and connection in the midst of pain. Her emphasis on attention, receptivity, and the renunciation of the false self provides a framework for therapeutic approaches that prioritize mindfulness, acceptance, and the cultivation of compassion. Moreover, Weil’s critique of oppressive power structures and her commitment to social justice serve as a reminder that individual healing and transformation cannot be separated from the larger project of collective liberation. Psychologists and therapists who are informed by her ideas may be called to not only address the immediate suffering of their clients but also to work towards dismantling the systemic and structural forces that contribute to this suffering.

Simone Weil’s life and thought offer a powerful testament to the human capacity for spiritual transformation and the search for meaning in the face of suffering and injustice. Her mystical vision, grounded in a deep concern for the oppressed and a radical critique of the self, continues to inspire and challenge those seeking to understand the complexities of the human psyche and the possibilities for healing and liberation. By engaging with Weil’s ideas, contemporary psychologists and therapists can develop new approaches to understanding and treating psychological distress, ones that prioritize mindfulness, compassion, and the embrace of suffering as a potential gateway to growth and connection. At the same time, her legacy serves as a call to action, reminding us of the urgent need to address the structural and systemic causes of suffering and to work towards a world of greater justice, solidarity, and love.

Weil’s Mysticism in Context

While Weil’s mystical philosophy was highly original, it also shared some key similarities and differences with other mystics throughout history. Like many Christian mystics, such as Meister Eckhart and St. John of the Cross, Weil emphasized the importance of self-renunciation and the embrace of suffering as a means of spiritual purification and union with the divine. However, Weil’s mysticism was less focused on ecstatic visions or supernatural experiences and more grounded in a stark confrontation with the reality of human affliction and injustice. In this sense, her approach bears some resemblance to the engaged Buddhism of Thich Nhat Hanh or the liberation theology of Gustavo Gutiérrez, which see spiritual practice as inextricably linked to social and political activism.

For Weil, writing was not merely an intellectual exercise but a spiritual discipline and a means of bearing witness to the truth of human suffering. She saw her role as a philosopher and mystic as one of illuminating the hidden structures of oppression and injustice, and of pointing the way towards a more authentic and compassionate way of being in the world. In this sense, Weil’s writing was deeply personal and yet also universal, grounded in her own experiences of affliction and solidarity while also speaking to the shared struggles and aspirations of humanity as a whole. Her ultimate purpose was not to create a systematic philosophy or to garner fame and recognition, but to serve as a channel for the transformative power of love and truth.

Weil and Depth Psychology

While Weil was not a psychologist in the formal sense, her insights into the nature of the self and the process of spiritual transformation bear some striking similarities to the depth psychology of Carl Jung and other psychoanalytic thinkers. Like Jung, Weil saw the ego as a kind of false self, a construct that needed to be stripped away in order to access a deeper level of spiritual reality. She also emphasized the importance of embracing the shadow side of the psyche, the aspects of ourselves that we tend to repress or deny, as a necessary step in the process of individuation and wholeness. However, Weil’s approach was less focused on the individual psyche in isolation and more attuned to the ways in which personal suffering and transformation are shaped by larger social and political forces. For therapists and counselors seeking to integrate Weil’s ideas into their practice, there are several key principles that can serve as a guide. First and foremost is the importance of cultivating a deep sense of empathy and attentiveness to the reality of clients’ suffering, without judgment or agenda. This means creating a space of radical acceptance and presence, where clients can explore the full range of their experiences and emotions without fear of rejection or stigma. It also means being willing to sit with the discomfort and uncertainty that often accompany deep psychological work, trusting in the transformative potential of the process.

Additionally, Weil’s emphasis on the spiritual dimensions of suffering and healing suggests the importance of incorporating contemplative practices and meaning-making into the therapeutic process. This could involve mindfulness techniques, guided imagery, or other forms of spiritual exploration, as well as helping clients to find a sense of purpose and connection beyond their individual struggles. Finally, Weil’s commitment to social justice and the alleviation of oppression calls for a therapeutic approach that is attuned to the ways in which systemic and structural factors shape individual experiences of distress and resilience. This could involve advocating for clients’ rights and access to resources, as well as working to dismantle the oppressive beliefs and practices that contribute to psychological harm. By integrating these principles into their work, therapists can help clients to not only heal from their own wounds but also to become agents of transformation in the world, embodying the kind of compassionate presence and engaged spirituality that Weil so powerfully exemplified.

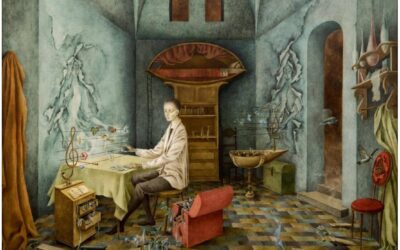

Weil’s Writing Style as a Reflection of Her Philosophy

Simone Weil’s distinctive writing style is not merely a matter of aesthetics but a direct reflection of her philosophical and spiritual vision. Her prose is characterized by a striking combination of clarity and complexity, directness and depth, that mirrors her dialectical approach to understanding the human condition. Weil’s writing is often aphoristic and fragmentary, eschewing systematic exposition in favor of a more experiential and intuitive mode of expression. This style reflects her belief in the limitations of abstract reasoning and her emphasis on the primacy of attention and receptivity in the face of reality.

One of the most notable features of Weil’s writing is her use of paradox and contradiction to convey spiritual truths. For example, she writes that “attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer,” suggesting that the act of fully attending to something, whether it be a mathematical problem or a human face, is a form of communion with the divine. Similarly, she asserts that “affliction is an uprooting of life, a more or less attenuated equivalent of death,” indicating that the experience of extreme suffering can be a kind of spiritual death and rebirth. These paradoxical statements reflect Weil’s belief in the ultimate unity of opposites and her desire to break through the limitations of dualistic thinking. Weil’s writing is also marked by a poetic and metaphorical quality that seeks to evoke spiritual realities rather than simply describe them. She frequently uses images drawn from nature, such as light, water, and plants, to convey the subtle dynamics of the inner life. For example, she compares the soul to a plant that must be continually uprooted in order to grow, suggesting that spiritual progress often involves a painful process of detachment and renunciation. At the same time, Weil’s writing is grounded in concrete, embodied experience, reflecting her commitment to a spirituality that is engaged with the world and its suffering.

Another key aspect of Weil’s writing style is her use of repetition and variation to create a sense of depth and resonance. She often returns to the same themes and images throughout her work, each time revealing new layers of meaning and insight. This iterative quality reflects her understanding of the spiritual life as a process of continual refinement and purification, in which the same truths must be encountered again and again at deeper levels of understanding. Weil’s writing is characterized by a profound sense of urgency and intensity, reflecting her belief in the vital importance of spiritual and political awakening. Her prose is often forceful and uncompromising, challenging readers to confront the reality of suffering and injustice and to respond with compassion and action. At the same time, her writing is infused with a deep sense of humility and reverence, recognizing the ultimate mystery and unknowability of the divine. In all these ways, Weil’s writing style embodies her unique philosophical and spiritual vision, inviting readers to enter into a transformative encounter with reality in all its complexity and depth. By attending closely to the rhythms and textures of her prose, we can begin to appreciate the full richness and subtlety of her thought, and to glimpse the radical possibilities for healing and liberation that she sought to illuminate.

“Decreation” in Weil’s Work

Weil’s concept of decreation, the stripping away of the false self to make space for the divine, bears striking similarities to the transformative processes described in various depth psychological and therapeutic traditions, including Jung’s idea of alchemical transformation, Roberto Assagioli’s concept of psychosynthesis, Gestalt therapy’s emphasis on self-awareness and contact, and Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy’s model of the self.

In Jungian psychology, the process of individuation is often compared to the alchemical process of transmuting base metals into gold. This involves a symbolic death and rebirth, as the ego is dissolved and reconstituted at a higher level of consciousness. Similarly, Weil’s decreation involves a kind of spiritual alchemy, in which the false self is “burned away” to reveal the pure gold of the authentic self. Both processes require a willingness to confront and integrate the shadow aspects of the psyche, the rejected or repressed parts of ourselves that we tend to project onto others.

Roberto Assagioli’s psychosynthesis also emphasizes the importance of self-transformation through the integration of various psychological functions and subpersonalities. Like Weil, Assagioli believed that the path to wholeness involved a process of disidentification from the ego and a surrendering to a higher spiritual reality. He used the image of a house to describe the psyche, with the ego residing on the ground floor and the higher self or soul on the upper floors. The work of psychosynthesis involves “furnishing” the upper rooms of the house, creating a space for the divine to enter and transform the personality.

Gestalt therapy, with its emphasis on present-moment awareness and the unity of mind and body, also shares some key principles with Weil’s philosophy. In Gestalt theory, the self is seen as an emergent property of the organism-environment field, rather than a fixed entity. The goal of therapy is to help clients develop greater self-awareness and contact with their environment, dissolving the barriers between self and other. This process of contact and withdrawal, figure and ground, bears some resemblance to Weil’s dialectical approach to the self and the world.

Finally, Internal Family Systems therapy, developed by Richard Schwartz, posits that the psyche is composed of various sub-personalities or “parts,” each with its own unique perspective and role. The goal of IFS is to help clients develop a greater sense of self-leadership, compassionately witnessing and integrating these different parts into a cohesive whole. This process of inner dialogue and reconciliation resembles Weil’s idea of attention and receptivity in the face of suffering, as well as her ultimate vision of the self united with God. While each of these therapeutic approaches has its own unique framework and techniques, they all share a fundamental commitment to the transformative power of self-awareness, acceptance, and integration. Like Weil’s philosophy, they recognize that the path to wholeness and healing often involves a painful process of letting go and surrendering to a greater reality beyond the ego. By drawing on these diverse traditions, contemporary therapists can help clients to cultivate the kind of radical attention and compassion that Weil saw as essential for spiritual growth and social justice. At the same time, Weil’s mystical vision and prophetic voice continue to challenge and inspire us to look beyond the confines of any single therapeutic approach, and to embrace the ultimate mystery and complexity of the human soul.

“It is only from the light which streams constantly from heaven that a tree can derive the energy to strike its roots deep into the soil. The tree is in fact rooted in the sky.”

— Simone Weil

Weil’s Conception of God and Self

In Simone Weil’s philosophy, the concepts of God and self are intimately intertwined and often paradoxical. For Weil, God is not a separate, anthropomorphic entity but rather the ultimate reality and ground of being. At the same time, she believed that the self, as conventionally understood, was an illusion and an obstacle to spiritual growth. In order to truly know God, one had to undergo a process of decreation, stripping away the false layers of the ego to reveal the divine spark within. Weil’s conception of God was deeply influenced by her readings of Plato, who posited a transcendent realm of perfect Forms beyond the world of appearances. Like Plato, Weil believed that ultimate reality was not to be found in the material world but in a higher, immaterial realm of truth and goodness. However, she also drew on Christian mystical traditions, particularly the apophatic or negative theology of Meister Eckhart and St. John of the Cross, which emphasized the ultimate unknowability and ineffability of God. For Weil, God was not a being among beings but the very ground of existence itself. In her essay “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” she writes, “God is not somewhere in the sky, he is in everything that is.” This immanent, pantheistic vision of God as the underlying reality of all things is balanced by an equally strong sense of God’s transcendence and otherness. Weil often uses paradoxical language to express this tension, as in her famous statement, “God is absent from the world, except in the existence of those in whom his love is alive.”

At the same time, Weil’s understanding of the self was marked by a deep skepticism towards the ego and its claims to autonomy and self-sufficiency. She believed that the self, as ordinarily conceived, was a kind of fiction or construct, an attempt to assert a separate identity in the face of the ultimate unity of all things. In order to truly know God, one had to undergo a process of decreation, a stripping away of the false layers of the ego to reveal the divine spark within.

One of the most striking examples of Weil’s paradoxical vision of God and self can be found in her statement to the French Resistance during World War II: “The tree is not rooted in the ground, it is rooted in the sky.” This enigmatic phrase suggests a radical inversion of the usual understanding of reality, in which the visible world of appearances is seen as the ultimate ground of being. For Weil, the true roots of existence are not to be found in the material world but in a higher, transcendent realm of truth and goodness. The tree, like the self, only appears to be separate and autonomous, but in reality, it is sustained by a divine source beyond itself. By recognizing this ultimate dependence on God, one can begin to let go of the illusion of the separate self and open oneself to the transformative power of divine love.

Another powerful image in Weil’s writing is the labyrinth, which she sees as a symbol of the spiritual journey. In her notebook, she writes, “The labyrinth which God has made for us is the labyrinth of our life in time. We think we are going forward, but we are only going towards the center. At the center, God is waiting to eat us.” This haunting image suggests that the path to spiritual transformation is not a straightforward one but rather a winding, circuitous journey that ultimately leads to a confrontation with the divine. The center of the labyrinth, where God is waiting to “eat us,” represents the point of ultimate surrender and self-emptying, in which the false self is consumed and transformed by the fire of divine love.

“The world is the closed door. It is a barrier. And at the same time it is the way through.

Two prisoners whose cells adjoin communicate with each other by knocking on the wall. The wall is the thing which separates them but it is also their means of communication. … Every separation is a link.”

― Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace

Weil’s Perspective on Religion

Simone Weil’s philosophy is characterized by a deep engagement with the nature of God and the human relationship to the divine. In her writings, she offers a unique perspective on two seemingly disparate phenomena: atheism and addiction. For Weil, both the atheist and the addict are grappling with the reality of God, albeit in different and ultimately incomplete ways. In her essay “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” Weil suggests that the atheist is not simply denying the existence of God but rather fixating on the impersonal aspects of the divine. She writes, “The atheist is one who has a conception of God. Only it is a wrong conception. He denies God conceived according to this conception. The atheist is therefore an idolater, with or without knowing it.” For Weil, the atheist’s rejection of God is based on a limited and ultimately distorted understanding of the divine as a personal being or a separate entity. In rejecting this anthropomorphic conception of God, the atheist is actually affirming the impersonal, transcendent reality that underlies all things. However, by fixating on this impersonal aspect of God to the exclusion of the personal, the atheist is missing the full truth of the divine nature.

Weil suggests that the way beyond atheism is not to simply affirm a personal God but rather to recognize the ultimate unity of the personal and impersonal aspects of the divine. She writes, “God is both personal and impersonal, and neither. He is transcendent with respect to this distinction.” By embracing this paradoxical understanding of God, one can begin to move beyond the limitations of both theism and atheism and enter into a deeper relationship with the divine. In a similar vein, Weil sees addiction as a misguided attempt to satisfy the soul’s hunger for God. In her book “Gravity and Grace,” she writes, “Every sin is an attempt to fly from emptiness.” For Weil, the addict is not simply seeking pleasure or escape but rather trying to fill the void within themselves that can only be satisfied by divine love. Weil suggests that the addict’s craving for their substance of choice is actually a distorted expression of the soul’s longing for God. In her essay “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” she writes, “The miser, the voluptuary, and the power-seeker are really God-seekers […] They are going in the wrong direction, but at least they have raised their eyes.”

In this sense, the addict is engaged in a kind of perverse spiritual quest, seeking to “eat God” through the consumption of finite substances. However, this attempt is ultimately doomed to failure, as no created thing can satisfy the infinite hunger of the soul. Weil writes, “We are like a man who is hungry and who dreams every night that he is eating his fill, but he awakes with his hunger intact.” The way beyond addiction, for Weil, is not simply to renounce the object of desire but rather to redirect that desire towards its true source in God. By recognizing the ultimate emptiness of created things and turning towards the divine love that alone can satisfy the soul, the addict can begin to find true healing and wholeness. Simone Weil’s reflections on atheism and addiction offer a profound challenge to our usual ways of thinking about these phenomena. By seeing the atheist and the addict as engaged in a misguided search for God, she invites us to look beyond the surface of their beliefs and behaviors and recognize the deeper spiritual hunger that drives them.

At the same time, her vision of God as both personal and impersonal, transcendent and immanent, challenges us to expand our own understanding of the divine and our relationship to it. By embracing the paradoxical nature of God and directing our desire towards its true source, we can begin to find the fulfillment and wholeness that we all seek. Ultimately, Weil’s philosophy is a call to radical honesty and self-emptying love, a willingness to confront the deepest longings of the soul and surrender them to the transformative power of divine grace. By following her example of attention and compassion, we can begin to awaken to the God who is always already present within us and find our true home in the heart of the divine.

The intelligent man who is proud of his intelligence is like the condemned man who is proud of his large cell.

Simone Weil

Weil’s Main Focus is on Love

“Love is a sign of our wretchedness. God can only love himself. We can only love something else.

God’s love for us is not the reason for which we should love him. God’s love for us is the reason for us to love ourselves. How could we love ourselves without this motive?

It is impossible for man to love himself except in this roundabout way.

If my eyes are blindfolded and if my hands are chained to a stick, this stick separates me from things but I can explore them by means of the stick. It is only the stick which I feel, it is only the wall which I perceive. It is the same with creatures and the faculty of love. Supernatural love touches only creatures and goes only to God. It is only creatures which it loves (what else have we to love?), but it loves them as intermediaries. For this reason it loves all creatures equally, itself included. To love a stranger as oneself implies the reverse: to love oneself as a stranger.

Love of God is pure when joy and suffering inspire an equal degree of gratitude.”

In this passage, Weil is exploring the nature of love and its relationship to God and creation. She suggests that human love is always mediated through created things, which serve as “intermediaries” between ourselves and God. Just as a person with blindfolded eyes and chained hands can only explore the world through the medium of a stick, so we can only love God through the medium of creatures.

This idea of love as a “roundabout way” of relating to God and ourselves is central to Weil’s philosophy. She sees love not as a direct connection between the self and the other, but rather as a kind of obstacle or separation that paradoxically allows for a deeper form of unity. By loving creatures as intermediaries, we are able to love God indirectly and to love ourselves as part of creation.

At the same time, Weil emphasizes the purity and equality of supernatural love, which touches all creatures equally and inspires gratitude in both joy and suffering. This love is not based on God’s love for us, but rather on the recognition of our own wretchedness and the need for a “motive” to love ourselves.

Weil’s vision of love as a “stick” that separates us from things while also allowing us to explore them is a powerful and paradoxical image that challenges our usual understanding of connection and separation. It suggests that our experience of love is always mediated and indirect, yet no less real or transformative for that fact.

By embracing this vision of love as a kind of obstacle or intermediary, we can begin to see our own limitations and dependencies in a new light, not as barriers to God but as the very means by which we can approach the divine. In loving creatures as strangers and strangers as ourselves, we participate in the mystery of God’s love for creation and find our true place in the web of interconnection that sustains us all.

Simone Weil’s Life and Work

Timeline of Simone Weil’s Life

Simone Weil’s Publications:

“Oppression and Liberty” (1934):

In this early work, Weil explores the nature of oppression and the conditions necessary for genuine human liberation. Drawing on her experiences as a factory worker and her philosophical reflections, Weil argues that oppression is rooted in the dehumanization of labor and the reduction of individuals to mere instruments of production. She calls for a radical reconceptualization of work, emphasizing the importance of creativity, autonomy, and the recognition of the inherent dignity of all human beings. Weil’s critique of the oppressive structures of modern industrial society lays the foundation for her later reflections on the nature of power, social justice, and the human condition.

“Waiting for God” (1942):

In this profound and deeply personal work, Weil grapples with the central questions of faith, suffering, and the human relationship to the divine. Written during her spiritual awakening, “Waiting for God” showcases Weil’s unique blend of philosophical rigor and mystical intensity. She explores the concept of “affliction,” the experience of extreme suffering that strips away the illusions of the self and reveals the fundamental reality of human vulnerability and dependence. Weil argues that it is through embracing this affliction and surrendering to the “void” of God’s apparent absence that one can paradoxically experience the fullness of divine love and grace. Her reflections on the nature of prayer, the meaning of the cross, and the call to self-renunciation continue to inspire and challenge readers seeking a deeper understanding of the spiritual life.

“The Need for Roots” (1949):

In this posthumously published work, Weil offers a penetrating analysis of the moral and spiritual crisis of modern society, rooted in what she sees as the uprooting of individuals from their cultural, historical, and spiritual traditions. She argues that the rise of totalitarianism and the dehumanizing tendencies of modern capitalism have created a profound sense of alienation and disconnection, leaving individuals adrift in a world without meaning or purpose. Weil calls for a renewed focus on the cultivation of roots, the nurturing of human communities based on shared values, mutual obligation, and a deep sense of belonging. Her vision of a society grounded in the principles of justice, compassion, and the sacred continues to inspire those seeking to build a more humane and sustainable world.

Timeline of Weil’s Life:

Early Life and Education

1909: Born in Paris to a wealthy, agnostic Jewish family.

1928: Enters the École Normale Supérieure, where she studies philosophy and excels academically.

1931: Graduates with a degree in philosophy and begins teaching in secondary schools.

Political Activism and Spiritual Awakening

1932: Joins unemployed workers in demonstrations and supports labor unions.

1934-1935: Takes a leave of absence from teaching to work in factories, experiencing firsthand the oppressive conditions of industrial labor.

1936: Participates in the Spanish Civil War, supporting the Republican cause against the Fascists.

1938: Undergoes a profound spiritual awakening, marked by mystical experiences and a growing interest in Christianity.

Exile and Final Years

1942: Flees Nazi-occupied France for the United States, where she works for the Free French resistance movement.

1943: Dies at the age of 34, likely from tuberculosis exacerbated by self-imposed asceticism and strict fasting.

Posthumous Publications and Legacy

1947: “Gravity and Grace,” a collection of Weil’s spiritual writings, is published posthumously.

1949: “The Need for Roots,” Weil’s reflections on the moral and spiritual foundations of society, is published.

1950s-Present: Numerous collections of Weil’s essays, letters, and notebooks are published, cementing her reputation as one of the most original and provocative thinkers of the 20th century.

Simone Weil’s life and work continue to inspire philosophers, theologians, and all those seeking to understand the depths of the human experience. Her uncompromising pursuit of truth, her solidarity with the oppressed, and her profound spiritual insights make her a unique and enduring voice in the history of modern thought.

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here.

Bibliography:

Weil, S. (1973). Gravity and Grace. Routledge. Weil, S. (2001). Waiting for God. HarperCollins. Weil, S. (2002). The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind. Routledge. Weil, S. (1973). Oppression and Liberty. University of Massachusetts Press. Weil, S. (1956). Notebooks of Simone Weil. Routledge & Kegan Paul. Weil, S. (1951). Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Further Reading:

Fiori, G. (1989). Simone Weil: An Intellectual Biography. Verso. McLellan, D. (1990). Utopian Pessimist: The Life and Thought of Simone Weil. Poseidon Press. Springsted, E. O. (1983). Simone Weil and the Suffering of Love. Cowley Publications. Perrin, J. M., & Thibon, G. (1953). Simone Weil as We Knew Her. Routledge & Kegan Paul. Nevin, T. R. (1997). Simone Weil: Portrait of a Self-Exiled Jew. University of North Carolina Press. Dunne, J. (1993). Back to the Rough Ground: “Phronesis” and “Techne” in Modern Philosophy and in Aristotle. University of Notre Dame Press. Blum, L. A. (1989). Compassion. In O. Flanagan & A. O. Rorty (Eds.), Identity, Character, and Morality: Essays in Moral Psychology (pp. 229-253). MIT Press. Vetö, M. (1994). The Religious Metaphysics of Simone Weil. State University of New York Press. Cabaud, J. (1964). Simone Weil: A Fellowship in Love. Harvill Press. Springsted, E. O. (1986). Simone Weil and the Suffering of Love. Cowley Publications.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Mystics and Gurus

0 Comments