How to Understand The Epic of Gilgamesh

What is the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest surviving works of literature, dated to around 2100 BCE. This Sumerian epic poem tells the story of Gilgamesh, the hero-king of Uruk, and his adventures with his wild-man companion Enkidu. On the surface, it is a tale of heroic exploits, friendship, loss, the search for immortality, and the acceptance of death. Yet when viewed through the lens of depth psychology, the Epic of Gilgamesh can be seen as a profound exploration of the journey of the soul, the development of consciousness, and the process of individuation.

Drawing upon the pioneering work of depth psychologists like Carl Jung, Erich Neumann, and Joseph Campbell, this essay will explore the psychological and symbolic dimensions of the Gilgamesh story. It will argue that the epic encodes perennial truths about the structure and evolution of the psyche, reflecting universal patterns of psychological development. The figures of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the other characters will be seen as personifications of different aspects of the psyche, while their journeys and trials will be interpreted as stages in the individuation process.

This depth psychological approach to the Gilgamesh epic has significant implications not only for the understanding of this ancient tale but also for the appreciation of myth and literature more broadly. By revealing the archetypal and symbolic layers of meaning in the story, it opens up new dimensions of psychological and spiritual insight. The essay aims to demonstrate the enduring relevance of this Mesopotamian epic for illuminating the depths of the human psyche and the perennial challenges of the human condition.

The Hero’s Journey and the Individuation Process

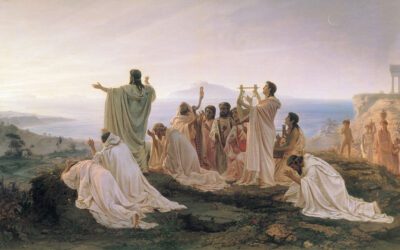

The narrative structure of the Epic of Gilgamesh closely follows the archetypal pattern of the hero’s journey, as described by comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell. In his seminal work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell identifies the basic stages of this monomyth: the call to adventure, the crossing of the threshold into the unknown, the road of trials, the supreme ordeal, the attainment of the boon, and the return and reintegration with society. This heroic cycle, he argues, symbolically expresses the process of psychological transformation and growth.

In the Gilgamesh story, these stages are clearly discernible. Gilgamesh, the young king of Uruk, is called to adventure when he is confronted with the wild man Enkidu, his destined friend and rival. Together, they cross the threshold into the cedar forest, the realm of supernatural danger, where they face the trials of battling the monster Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. Gilgamesh’s supreme ordeal comes with the death of Enkidu, which propels him on a quest for immortality. He finally attains the boon of wisdom and acceptance when he fails to achieve everlasting life and returns to Uruk to live out his days as a just and wise ruler.

From a Jungian perspective, this heroic cycle can be seen as a symbolic representation of the individuation process – the lifelong journey of psychological development whereby the ego becomes increasingly differentiated from the unconscious and integrated with the deeper layers of the psyche. The hero’s journey from the known to the unknown and back again mirrors the ego’s encounter with the unconscious, the assimilation of its contents, and the return to conscious life on a higher level of awareness and wholeness.

In this light, Gilgamesh’s story is not just a literal account of a king’s adventures but a mythic expression of the universal human journey towards self-realization. His trials and triumphs, his descents and ascents, reflect the archetypal process of navigating between the conscious and unconscious worlds, of integrating the light and shadow aspects of the psyche. As Edward Edinger writes in Ego and Archetype, “The hero myth…is an image of the development of the ego as it separates from the unconscious and then returns to establish a mature relationship with it.”

Gilgamesh and the Inflated Ego

At the beginning of the epic, Gilgamesh is described as a powerful and heroic figure, but also as a tyrannical and oppressive ruler. He is said to be two-thirds divine and one-third human, and his superhuman strength and energy are emphasized. However, he is also portrayed as arrogant, impulsive, and prone to abusing his power, taking what he wants and trampling on the rights of his subjects.

In psychological terms, Gilgamesh at this stage represents the inflated ego – the immature, unreflective ego that has not yet been tempered by contact with the unconscious. The inflated ego overestimates its own powers and importance, and seeks to dominate and control its environment. It is cut off from the deeper layers of the psyche, and lacks self-awareness and humility.

This aspect of Gilgamesh is vividly illustrated in the early episodes of the epic, such as his droit du seigneur (the right of the lord to sleep with brides on their wedding night) and his harsh treatment of the young men of Uruk. His subjects cry out to the gods for relief from his oppression, prompting the creation of Enkidu as a counterbalance to Gilgamesh’s power.

In Jungian theory, the inflation of the ego is a common stage in psychological development, particularly in the first half of life. The ego must first develop a sense of its own strength and agency before it can relativisitself and recognize its place within the larger fabric of the psyche. However, if the ego remains in this inflated state, it risks becoming cut off from its unconscious roots and falling into stagnation or destruction.

Gilgamesh’s journey, then, can be seen as a process of ego-deflation – of the gradual diminishment of the ego’s grandiosity and the development of a more balanced and integrated self. This process begins with his encounter with Enkidu, his double and shadow.

Enkidu as Gilgamesh’s Shadow

Enkidu, the wild man created by the gods to challenge Gilgamesh, is in many ways the opposite of the king. Where Gilgamesh is cultured, civilized, and urban, Enkidu is rustic, savage, and at home in the wilderness. Where Gilgamesh is restless and aggressive, Enkidu is content and peaceful in his communion with nature and animals.

In Jungian terms, Enkidu represents Gilgamesh’s shadow – the repressed, unconscious aspects of his personality that he has rejected or denied. The shadow is all that we are not conscious of, all that we have not developed or acknowledged in ourselves. It often contains qualities that are opposite to our conscious self-image, and that we project onto others.

For Gilgamesh, Enkidu embodies all that he has sacrificed or lost in his pursuit of power and glory – his connection to nature, his capacity for simple joys and friendships, his instinctual wisdom. Enkidu is the uncivilized, natural man that Gilgamesh has left behind in his ascent to kingship and heroism.

The initial conflict between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, culminating in their wrestling match, can be seen as the ego’s first confrontation with the shadow. The ego naturally resists and seeks to dominate the shadow, seeing it as a threat to its sovereignty. But through the struggle, the ego begins to recognize the shadow as a part of itself, and to integrate its qualities.

This is precisely what happens with Gilgamesh and Enkidu. After their combat, they embrace and become fast friends, forming a bond of love and loyalty that will carry them through their subsequent adventures. Psychologically, this represents the ego’s acceptance and assimilation of the shadow, leading to a more whole and balanced personality.

As Erich Neumann writes in The Origins and History of Consciousness, the integration of the shadow is a crucial step in the individuation process: “The shadow personifies everything that the subject refuses to acknowledge about himself and yet is always thrusting itself upon him directly or indirectly. . . . The realization of the shadow, which is at first a process of disillusionment, leads to humility, the insight that the self has limits and is not identical with its own light.”

The Shadow and the Animal Soul

Enkidu’s role as Gilgamesh’s shadow is further underscored by his close association with animals. When he is first created, Enkidu lives amongst the beasts, grazing and drinking with them at the watering hole. He is hairy, savage, and ignorant of human ways, more animal than man.

In many cultures, animals are symbolic of the instinctual, unconscious layers of the psyche – what Jung called the “animal soul.” They represent the primal, chthonic energies of nature, the untamed wildness of the id. Enkidu’s animal nature thus points to his embodiment of all that is unconscious and instinctive in Gilgamesh.

The process of Enkidu’s civilization, his gradual humanization through contact with the priestess Shamhat and the shepherds, can be seen as the cultivation and refinement of the animal soul. Just as Enkidu learns to eat bread, drink wine, and wear clothes, so too the raw energies of the unconscious must be tempered and integrated into the conscious personality.

But this process of civilization is not without its costs. In becoming human, Enkidu loses his primal innocence and his harmony with nature. The animals flee from him, no longer recognizing him as one of their own. He has gained knowledge and consciousness, but at the price of his instinctual wholeness.

This theme of the loss of animal innocence through the acquisition of consciousness is a common one in myth and depth psychology. It is echoed in the biblical story of the Fall, where Adam and Eve’s eating from the Tree of Knowledge marks their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. It is also reflected in the psychoanalytic notion of the Oedipus complex, where the child’s development of ego-consciousness entails a separation from the primal union with the mother.

For Gilgamesh, too, the friendship with Enkidu and the integration of his animal soul is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it leads to a greater wholeness and balance of personality, a tempering of his fiery heroic nature. On the other hand, it also exposes him to the pains of love and loss, and to the ultimate reality of death.

The Sacred Marriage and the Anima

The friendship of Gilgamesh and Enkidu is often interpreted as a kind of platonic same-sex partnership. But from a depth psychological standpoint, it can also be seen as an inner marriage of masculine and feminine energies, of ego and soul.

In Jungian theory, the soul or anima is the feminine aspect of a man’s psyche, the inner counterpart to his masculine ego-consciousness. The anima represents all that is receptive, intuitive, and nurturing in the psyche – qualities that are often repressed or undervalued in patriarchal societies.

Enkidu, though male, embodies many traditionally feminine characteristics. He is gentle, empathetic, and closely attuned to nature. He tempers Gilgamesh’s aggressive, warlike tendencies and teaches him the value of friendship and love. In this sense, he can be seen as Gilgamesh’s anima figure, his soul-companion.

The union of Gilgamesh and Enkidu thus represents what Jung called the “sacred marriage” – the conjunctio or inner alchemical wedding of masculine and feminine energies. This sacred marriage is a key stage in the individuation process, leading to a greater wholeness and balance of the psyche.

As Robert Bly writes in his book Iron John, the sacred marriage is the hero’s reward for his trials and ordeals:

“The sacred marriage involves a Hieros Gamos ceremony in which the hero encounters the feminine, either in the form of God’s Queen of Heaven or the Goddess of Earth. By loving the Goddess, the hero gains his own soul. . . . For men in our culture, it is the woman inside us, the unconscious, the soma, whom we must travel far to meet.”

The union of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, their loving bond and shared adventures, can be seen as a mythic image of this inner sacred marriage. Through their relationship, Gilgamesh begins to integrate his anima and to develop a more soulful, balanced masculinity.

The Monster as Threshold Guardian

After becoming friends, Gilgamesh and Enkidu set out on a series of heroic adventures, the first of which is the battle with Humbaba, the monstrous guardian of the Cedar Forest. This episode marks their crossing of the first threshold of the hero’s journey, the entry into the realm of supernatural danger.

In Campbell’s monomyth, the hero’s passage across the threshold is often blocked by a “threshold guardian” – a fearsome monster or demon that must be overcome before the journey can continue. The hero must summon all his courage and skill to defeat this guardian and gain entry to the new world.

Humbaba clearly fits this archetypal role. He is a terrifying giant, appointed by the god Enlil to guard the sacred cedars from human intrusion. He is described as having the face of a lion, the talons of an eagle, and a body covered in horny scales. His roar is like a flood, his breath like fire, and his jaws like death itself.

Psychologically, the threshold guardian represents the ego’s fear of the unknown, its resistance to change and transformation. The monster embodies all the anxieties and insecurities that arise when the ego is challenged to leave its familiar world and confront the mysteries of the unconscious.

Humbaba can thus be seen as a projection of Gilgamesh’s own inner demons, the shadows that he must overcome in order to grow and individuate. By facing and defeating the monster, Gilgamesh proves his heroic mettle and gains access to a new level of self-knowledge and power.

Interestingly, Enkidu at first opposes the fight with Humbaba, urging Gilgamesh to turn back. This hesitation reflects the natural reluctance of the unconscious to change, its fear of losing its primal innocence. But Gilgamesh’s determination wins out, and Enkidu agrees to stand by his friend in battle.

The confrontation with Humbaba is a pivotal moment in Gilgamesh’s psychological development. By vanquishing the monster-guardian, he crosses the threshold from the known to the unknown, from the safe confines of the ego to the perilous depths of the unconscious. He emerges victorious but also fundamentally changed, having tasted the wonder and terror of the numinous.

The Forest as the Realm of the Unconscious

The Cedar Forest itself is rich in psychological symbolism. Forests, in myth and literature, are often depicted as dark, mysterious places, the abode of magic and danger. They represent the unconscious realm of the psyche, the untamed wilderness of instinct and imagination.

In fairy tales like “Hansel and Gretel” or “Little Red Riding Hood,” the forest is the place where the hero gets lost and must confront supernatural threats in order to find the way back home. It is a liminal zone, a place of initiation and transformation, where the old identity is shed and a new one is forged.

The Cedar Forest in the Gilgamesh epic serves a similar symbolic function. It is a place of mystery and danger, guarded by the fearsome Humbaba. Its cedars are sacred to the gods, not to be cut down by mortal men. By entering the forest, Gilgamesh and Enkidu are venturing into the unknown, the realm of the supernatural.

Psychologically, their journey into the Cedar Forest represents the ego’s descent into the unconscious, the exploration of the deep psyche. It is a journey of self-discovery and self-transcendence, where the hero must confront the shadows and marvels hidden within his own soul.

The felling of the sacred cedars, though a seemingly hubristic act, can be seen as a necessary part of this process. It represents the ego’s assertion of its own will and agency, its capacity to shape and transform the raw materials of the unconscious. By cutting down the trees, Gilgamesh is in effect harvesting the energies of the deep psyche and using them for his own growth and individuation.

But this act of heroic assertion is not without consequences. The destruction of the cedars angers the gods, particularly Enlil, who had appointed Humbaba as their guardian. Gilgamesh’s triumph over the unconscious is thus a double-edged sword – it leads to growth and self-knowledge but also incurs the wrath of the transpersonal powers.

This motif of the hero’s sacrilege, his transgression against the gods, is a common one in mythology. It reflects the ego’s inherent hubris, its tendency to overreach its proper bounds and incur nemesis or divine retribution. Gilgamesh’s victory in the Cedar Forest is thus both a psychological triumph and a spiritual error, one that will have fateful consequences later in the story.

The Bull of Heaven and the Mother Complex

After slaying Humbaba, Gilgamesh and Enkidu return to Uruk as heroes. But their triumph is short-lived, as they soon face a new challenge in the form of the Bull of Heaven, sent by the goddess Ishtar to punish Gilgamesh for spurning her advances.

Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, represents the archetype of the Great Mother, the feminine power of creation and destruction. When Gilgamesh refuses her offer of marriage, citing the fate of her previous lovers, he is in effect rejecting the power of the Great Mother, asserting his independence from the matriarchal unconscious.

Ishtar’s rage at this rejection takes the form of the Bull of Heaven, a monstrous creature that causes widespread destruction and death. The bull is a common symbol of masculine potency and aggression, but also of the destructive aspect of the feminine. In this context, it represents the vengeful fury of the rejected Great Mother, her power to emasculate and destroy.

Psychologically, Gilgamesh’s refusal of Ishtar can be seen as the ego’s necessary separation from the maternal unconscious, its assertion of its own masculine identity. But this separation is never complete or easy, and often provokes a backlash from the unconscious in the form of neurosis or inner conflict.

The Bull of Heaven thus represents what Jung called the “mother complex” – the dysfunctional attachment to the maternal that can hinder masculine development. By clinging to the security and power of the mother, the ego fails to fully individuate and assert its own agency. It remains caught in a regressive, dependent state.

Gilgamesh’s battle with the Bull of Heaven, aided by Enkidu, is therefore a pivotal moment in his psychological development. By slaying the bull, he overcomes the regressive pull of the mother complex and asserts his heroic masculinity. He proves his capacity to stand alone, separate from the maternal matrix.

But again, this triumph comes at a cost. By killing the Bull of Heaven, Gilgamesh and Enkidu have angered the gods and upset the balance of nature. Their heroic victory is also an act of hubris, a transgression against the divine order. They have, in effect, overreached the proper bounds of the ego and incurred the wrath of the unconscious.

The Death of Enkidu and the Descent into the Underworld

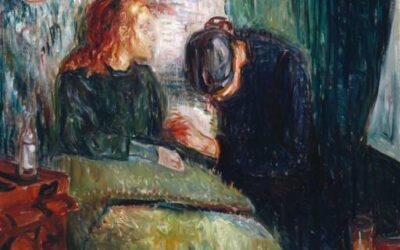

This nemesis takes the form of Enkidu’s death, decreed by the gods as punishment for the slaying of Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. Enkidu’s death is the pivotal event of the epic, the crisis that propels Gilgamesh on his quest for immortality and self-knowledge.

On a psychological level, Enkidu’s death represents the loss of the animathe feminine soul-mate that had previously complemented and balanced Gilgamesh’s masculine ego. With Enkidu gone, Gilgamesh is thrown back upon himself, forced to confront his own mortality and incompleteness.

Gilgamesh’s grief for Enkidu is thus not just a personal sorrow but an existential crisis, a realization of the ultimate aloneness and finitude of the ego. As he wanders the wilderness in mourning, Gilgamesh is forced to confront the reality of death and the limits of his heroic power.

This confrontation with mortality is a key stage in the individuation process. It marks the ego’s realization of its own contingency and relativity, its dependence on forces beyond its control. The death of a beloved other is often the catalyst for this realization, shattering the ego’s illusions of immortality and invincibility.

Gilgamesh’s journey to the underworld in search of his ancestor Utnapishtim is thus a mythic image of the ego’s descent into the depths of the unconscious, the realm of death and transformation. By confronting the reality of mortality, Gilgamesh is forced to let go of his heroic inflation and develop a more humble, realistic sense of self.

This descent into the underworld is a common motif in mythology, often symbolizing a journey of initiation and rebirth. In the Greek myth of Orpheus, for example, the hero descends to Hades to retrieve his dead lover Eurydice, much as Gilgamesh seeks out Utnapishtim to learn the secret of immortality.

Psychologically, this descent represents the ego’s willingness to confront and integrate the dark, chthonic aspects of the psyche – what Jung called the “shadow” and the “anima.” By journeying into the underworld of the unconscious, the hero seeks to reconcile the opposites within himself and attain a higher level of self-knowledge.

But this journey is perilous and not always successful. Gilgamesh ultimately fails to attain immortality, losing the magic plant that would have restored his youth. He returns to Uruk empty-handed, forced to accept the reality of his own mortality.

This acceptance of death is the final stage of Gilgamesh’s psychological development. By relinquishing his heroic quest for immortality, he attains a new level of wisdom and maturity. He becomes a true king, ruling his city with justice and compassion, no longer driven by the demons of his own ego.

The Wisdom of Acceptance and the Return to the City

In the end, Gilgamesh’s journey is one of disillusionment and acceptance. He sets out as a heroic warrior, eager to prove his might and win eternal fame. But through his adventures and losses, he learns the limits of heroic individualism and the necessity of humility and community.

Gilgamesh’s ultimate wisdom is the wisdom of acceptance – acceptance of mortality, of human finitude, of the cyclical nature of life and death. By embracing his own limitations and relativity, he paradoxically transcends them, attaining a new level of consciousness and inner peace.

This wisdom is symbolized by Gilgamesh’s return to Uruk and his dedication to the city’s welfare. No longer seeking individual glory, he becomes a servant of the collective, working for the good of his people. He channels his energies into building and creating rather than battling and destroying.

In psychological terms, this represents the ego’s integration with the larger Self, its willingness to serve the greater whole rather than its own narrow interests. The individuated ego recognizes its place within the larger mandala of the psyche and works to harmonize and balance the various forces within.

Gilgamesh’s return to Uruk can also be seen as a return to the feminine, the maternal matrix of civilization and culture. After his heroic adventures and confrontations with the masculine energies of the wilderness, he comes back to the city, the embodiment of the feminine principle of containment and nurture.

This return to the feminine is a necessary counterbalance to the masculine thrust of the hero’s journey. It represents the integration of the anima, the inner feminine, and the recognition of the ego’s ultimate dependence on the Great Mother of the unconscious.

As Erich Neumann writes in The Origins and History of Consciousness:

“The hero myth in which the male overcomes the Terrible Mother is only one side of the story. The other side shows the male as an infantile figure who is overcome and sucked in by the Terrible Mother. . . . The hero’s victory over the feminine is thus only a partial solution of the masculine-feminine problem. The final stage demands a reconciliation of the opposites.”

Gilgamesh’s story, seen in this light, is not just a tale of heroic exploits but a myth of psychological wholeness – of the reconciliation of masculine and feminine, ego and unconscious, civilization and nature. His journey is a model of the individuation process, the lifelong struggle to integrate the disparate parts of the psyche.

The Relevance of Gilgamesh for Modern Psychology

The Epic of Gilgamesh, though ancient, has lost none of its psychological relevance for modern readers. Its themes of friendship, loss, the fear of death, and the search for meaning are as pressing today as they were in ancient Mesopotamia.

For depth psychologists, the epic is a treasure trove of archetypal symbolism and psychological insight. Its characters and motifs – the hero, the shadow, the anima, the underworld journey, the sacred marriage – are key elements of the Jungian worldview, reflecting deep structures of the psyche.

Gilgamesh’s story can be seen as a paradigm of the individuation process, the hero’s journey towards wholeness and self-realization. His adventures and trials mirror the challenges faced by every individual in the struggle to mature and integrate the psyche.

At the same time, the epic also reflects the collective psychological development of humanity as a whole. Gilgamesh’s journey from heroic individualism to self-transcendence and service to the community can be seen as a model for the evolution of human consciousness itself.

In our own time, as we face the challenges of environmental catastrophe, social fragmentation, and existential uncertainty, the lessons of Gilgamesh are more relevant than ever. The epic reminds us of the necessity of humility, the limits of heroic ego-consciousness, and the ultimate interdependence of humanity and nature.

As we seek to navigate the perils of the modern world, we would do well to heed the wisdom of Gilgamesh – to embrace our own finitude, to serve the greater whole, and to seek a harmonious balance between the forces of ego and unconscious, masculine and feminine, civilization and wildness.

In the end, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a testament to the enduring power of myth to illuminate the depths of the human soul. Its ancient symbols and motifs still resonate with us today because they reflect universal patterns of psychological development and transformation.

By engaging with this timeless story, we connect with the collective unconscious, the shared wellspring of human experience. We find guidance and inspiration for our own journeys of self-discovery and individuation.

As the late mythologist Joseph Campbell wrote:

“Myths are public dreams, dreams are private myths. By finding your own dream and following it through, it will lead you to the myth-world in which you live. But just as in dream, the subject and object, though they seem to be separate, are really the same.”

The Epic of Gilgamesh, in the end, is not just a story of a long-dead king but a living myth, a dream of the human soul. By entering into its world and walking with its heroes, we come to know ourselves more deeply and to find our place in the great drama of existence.

So let us journey with Gilgamesh, through the wild forests and the dark underworld of the psyche, to the shining city of the Self. Let us learn, with him, the wisdom of acceptance and the power of myth to guide us home.

References

- Burkert, Walter. Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual. University of California Press, 1979.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New World Library, 2008.

- Dalley, Stephanie, trans. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Edinger, Edward F. The Eternal Drama: The Inner Meaning of Greek Mythology. Shambhala, 2001.

- Ellwood, Gracia Fay. “C. G. Jung and His Psychology of Religion.” Journal of Bible and Religion 33, no. 3 (July 1965): 215–21.

- Ellwood, Robert S. The Politics of Myth: A Study of C. G. Jung, Mircea Eliade, and Joseph Campbell. SUNY Press, 1999.

- Frank, Jerome D. “The Psychological Aspects of Myths and Rites.” American Journal of Psychotherapy 5, no. 1 (January 1951): 40–57.

- Freud, Sigmund. The Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud. Translated by A. A. Brill. Modern Library, 1995.

- George, Andrew, trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian. Penguin, 2003.

- Heidel, Alexander, trans. The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels. University of Chicago Press, 1963.

- Henderson, Joseph L. Thresholds of Initiation. Wesleyan University Press, 1967.

- Hillman, James. The Dream and the Underworld. Harper & Row, 1979.

- Jacobi, Jolande. “Symbols in an Individual Analysis.” In Man and His Symbols, edited by C. G. Jung and M. L. von Franz. Doubleday, 1964.

- Jacoby, Mario. Individuation and Narcissism: The Psychology of the Self in Jung and Kohut. Routledge, 1991.

- Jung, C. G. Symbols of Transformation. Princeton University Press, 1956.

- Jung, C. G., and C. Kerényi. Essays on a Science of Mythology. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton University Press, 1969.

- Jung, C. G., Joseph L. Henderson, Marie-Louise von Franz, Aniela Jaffé, and Jolande Jacobi. Man and His Symbols. Doubleday, 1964.

- Kerenyi, C. Prometheus: Archetypal Image of Human Existence. Princeton University Press, 1997.

- Langdon, Stephen. The Epic of Gilgamish. Clarendon Press, 1917.

- Maier, John R. “Gilgamesh the King of Joy.” Comparative Literature Studies 12, no. 1 (January 1975): 1–32.

- Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype. Translated by Ralph Manheim. Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Neumann, Erich. The Origins and History of Consciousness. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton University Press, 1970.

- Otto, Rudolf. The Idea of the Holy. Translated by John W. Harvey. Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Perera, Sylvia Brinton. Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women. Inner City Books, 1981.

- Sandars, Nancy K., trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Penguin Classics, 1972.

- Shaw, Miranda. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Tigay, Jeffrey H. The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2002.

- Van der Leeuw, G. Religion in Essence and Manifestation: A Study in Phenomenology. Harper Torchbooks, 1963.

- West, M. L. The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. Clarendon Press, 1999.

- Wolff, Toni. “Structural Forms of the Feminine Psyche.” In The Feminine in Fairy Tales, edited by Irene Claremont de Castillejo. Spring Publications, 1973.

0 Comments