From Jewish Messiah to Greco-Roman Hero: The Transformations of Jesus in Early Christianity

The story of Jesus Christ is undoubtedly one of the most influential narratives in human history. But the Jesus we know today – the divine-human savior who died and rose again for the salvation of the world – is in many ways a product of the complex cultural and religious milieu of the ancient Mediterranean.

To understand how the Jewish Messiah became the cosmic Christ of Christian faith, we must explore the profound transformations that the Jesus narrative underwent in the centuries after his death. In particular, we must consider how the early Christian movement, in its efforts to spread the gospel message to the wider Greco-Roman world, adapted and reinterpreted the story of Jesus to align with the heroic archetypes and mythic patterns of classical pagan culture.

The Jewish Messiah: A Savior for Israel

To grasp the significance of these transformations, we must first understand the original context of the Jesus story within Jewish messianic tradition. In ancient Israelite prophecy and apocalyptic literature, the Messiah was envisioned as a divinely appointed savior who would liberate the Jewish people from foreign oppression and establish a new age of peace and justice. This messianic figure was often portrayed as a royal descendant of King David who would restore the glories of Israel’s ancient monarchy.

However, the Jewish Messiah was not typically depicted as a divine being or a cosmic redeemer. Rather, he was understood as a human agent of God’s will, chosen to fulfill a specific historical and political role on behalf of the Jewish nation. The Messiah’s mission was to bring about the redemption of Israel, not necessarily the salvation of all humanity.

This is the context in which Jesus of Nazareth initially emerged as a messianic claimant. The earliest traditions about Jesus, preserved in the synoptic gospels and other early Christian writings, present him as a Jewish prophet and wonder-worker who preached the coming of God’s kingdom and challenged the religious and political authorities of his day. While Jesus’ followers came to see him as the promised Messiah, their understanding of his identity and mission was still deeply rooted in Jewish apocalyptic expectation.

The Greco-Roman Hero: A Model for Transformation

However, as Christianity began to spread beyond its Jewish origins into the wider Greco-Roman world, the story of Jesus underwent a profound metamorphosis. To make the gospel message compelling to pagan audiences, early Christian evangelists and theologians had to translate the Jewish Messiah into a heroic figure that would resonate with the mythic imagination of classical culture.

In the Greek and Roman world, the hero was a central figure of religious and literary tradition. Heroes like Heracles, Odysseus, and Aeneas were celebrated as models of virtue, courage, and divine favor. But what set these heroes apart was not just their great deeds, but their transformative journeys, particularly their descent into the underworld.

The hero’s journey to the realm of the dead, known as the katabasis, was a common motif in Greek and Roman myth. This terrifying voyage was seen as the ultimate test of the hero’s mettle, a liminal experience that marked the transition from mortal to immortal status. By descending into the underworld and returning alive, the hero demonstrated his exceptional nature and proved his worthiness for divine honors.

This mythic pattern of death, descent, and resurrection became a powerful template for early Christian reinterpretations of the Jesus story. By portraying Christ as a divine hero who descended into the depths of Hades and emerged victorious over the powers of death, Christian theologians could present the gospel in terms that would be both familiar and compelling to pagan audiences.

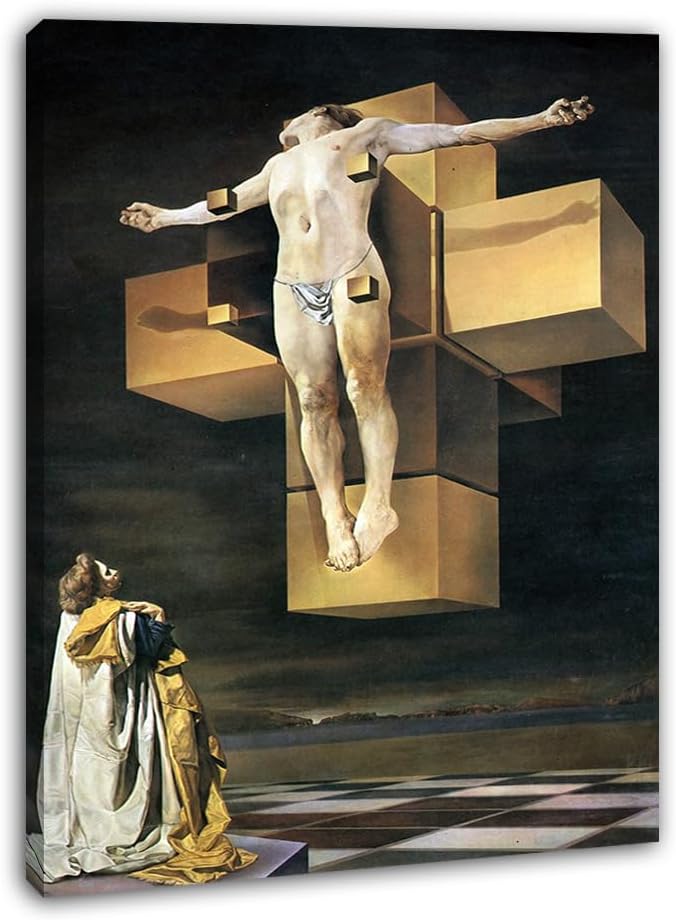

The Harrowing of Hell: Christ as Epic Hero

One of the most striking examples of this Christianization of the Greco-Roman hero myth is the tradition of the Harrowing of Hell. This story, which became a central theme in medieval Christian art and literature, depicts Christ’s descent into the underworld in the days between his crucifixion and resurrection.

According to this tradition, Christ stormed the gates of Hades, confronted the devil, and liberated the righteous souls who had been imprisoned there since the beginning of time. This dramatic tale of cosmic combat and redemption echoes the katabasis narratives of Greek and Roman epic, particularly the underworld journeys of Odysseus and Aeneas.

But the Harrowing of Hell is more than just a Christian appropriation of pagan myth. It represents a profound transformation of the Jewish messianic idea into a universalist vision of divine salvation. By portraying Christ as a hero who descends into the depths to rescue all the lost souls of history, the Harrowing myth expands the scope of redemption beyond the confines of Israel to encompass the entire cosmos.

Moreover, the Harrowing of Hell narrative introduces a new dimension to the idea of the hero’s transformative journey. In classical myth, the hero’s katabasis was primarily a personal ordeal, a test of individual virtue and courage. But in the Christian vision, Christ’s descent becomes an act of cosmic redemption, a sacrificial journey undertaken for the sake of all humanity. The hero’s transformation, in this sense, is not just a personal apotheosis but a universal one, a redemptive act that heals the rift between the divine and the human.

Pagan Echoes: The Assimilation of Greco-Roman Culture

The influence of Greco-Roman myth on early Christianity extends far beyond the heroic motif of the katabasis. As the new faith spread throughout the Mediterranean world, it absorbed and assimilated a wide range of pagan cultural elements, from philosophical ideas to religious rituals and symbols.

One of the most notable examples of this cultural syncretism is the dating of Christmas to December 25th. This date, which coincides with the winter solstice, was originally associated with the birth of various pagan solar deities, such as the Roman Sol Invictus and the Persian Mithra. By adopting this date for the celebration of Christ’s birth, the early church was able to tap into the symbolic power of the solstice and present Jesus as the true light of the world.

Other pagan symbols and motifs that found their way into Christian tradition include the Christmas tree, which may have originated in the cult of the Germanic god Woden, and the pomegranate, a fruit associated with the Greek goddess Persephone and her own mythic descent into the underworld. Even the figure of Jesus himself was sometimes depicted in ways that echoed pagan iconography, such as the image of Christ as the Good Shepherd, which parallels representations of the Greek god Hermes.

These pagan influences were not always welcomed by Christian authorities, and there were periodic efforts to purge the church of “heathen” elements. But the assimilation of Greco-Roman culture proved to be an essential factor in Christianity’s success and spread. By adapting to the cultural milieu of the ancient Mediterranean, the early church was able to present the gospel message in terms that resonated with a wide range of peoples and traditions.

The Enduring Power of Myth

The transformation of Jesus from Jewish Messiah to Greco-Roman hero is a fascinating example of the ways in which religious narratives evolve and adapt as they cross cultural boundaries. By recasting the story of Jesus in the mold of classical myth, early Christianity was able to present a compelling and culturally relevant vision of divine salvation to the pagan world.

But this process of mythic assimilation was not just a matter of superficial accommodation. The integration of Greco-Roman heroic themes into the Christian narrative also reflects a deeper psychological and spiritual truth – the universal human longing for transformation, redemption, and transcendence.

In this sense, the story of Jesus’ descent into the underworld is more than just a Christian appropriation of pagan myth. It is a powerful symbol of the journey that each of us must undertake, a call to confront the darkness within and without, and to emerge reborn into a new life.

As the psychologist Carl Jung recognized, the hero’s journey is a potent archetype of the human psyche, a template for the process of individuation and self-realization. By descending into the depths of the unconscious and facing the shadows of the self, we can undergo a profound transformation, a death and rebirth of the ego that leads to greater wholeness and authenticity.

In the end, the enduring power of the Jesus story lies not just in its historical or theological significance, but in its ability to speak to the deepest longings and aspirations of the human heart. Whether we approach it as a matter of faith or as a mythic archetype, the tale of the hero’s descent and resurrection continues to inspire and challenge us, calling us to embark on our own journeys of transformation and redemption.

TAGS: Christianity, Greco-Roman culture, myth, hero’s journey, Jesus Christ, katabasis, individuation, Jewish Messiah, Harrowing of Hell, paganism, Carl Jung, syncretism, Sol Invictus, Mithraism

Bibliography:

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, 1949.

- Eliade, Mircea. The Myth of the Eternal Return: Cosmos and History. Princeton University Press, 1954.

- Freke, Timothy, and Peter Gandy. The Jesus Mysteries: Was the “Original Jesus” a Pagan God? Harmony, 1999.

- Jung, Carl Gustav. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press, 1959.

- Klauck, Hans-Josef. The Religious Context of Early Christianity: A Guide to Graeco-Roman Religions. Fortress Press, 2003.

- Price, Robert M. “The Christ Myth Theory and Its Problems.” Atheist Alliance International, 2011.

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Harvard University Press, 1985.

- Koester, Helmut. Introduction to the New Testament: History and Literature of Early Christianity. Walter de Gruyter, 2000.

0 Comments