*This review contains spoilers for the film The Boy and the Heron

What is The Boy and the Heron trying to tell us?

To escape from this depressing situation, they often find themselves wishing they could live in a world of their own – a world they can say is truly theirs, a world unknown even to their parents. To young people, anime is something they incorporate into this private world.

I often refer to this feeling as one yearning for a lost world. It’s a sense that although you may currently be living in a world of constraints, if you were free from those constraints, you would be able to do all sorts of things. And it’s that feeling, I believe, that makes mid-teens so passionate about anime.”

― Hayao Miyazaki, Starting Point 1979-1996

The Boy and the Heron may be one of Miyazaki’s most challenging and personal films. Viewers may not understand the underlying assumptions that make up its implicit messages and extended metaphors. There is not one interpretation but moreover a language that Miyazaki speaks in that, even when understood well, does not communicate a singular message or define a unipolar meaning. Some biographic elements are unmissable – Miyazaki’s relationship with his own parents is present but not the point. Miyazaki’s father is working on a post-war peaceful quest for a better world through design and manufacturing, while Miyazaki himself is working on a post-war peaceful project through the artistic and imaginative.

The Language of The Unconcious

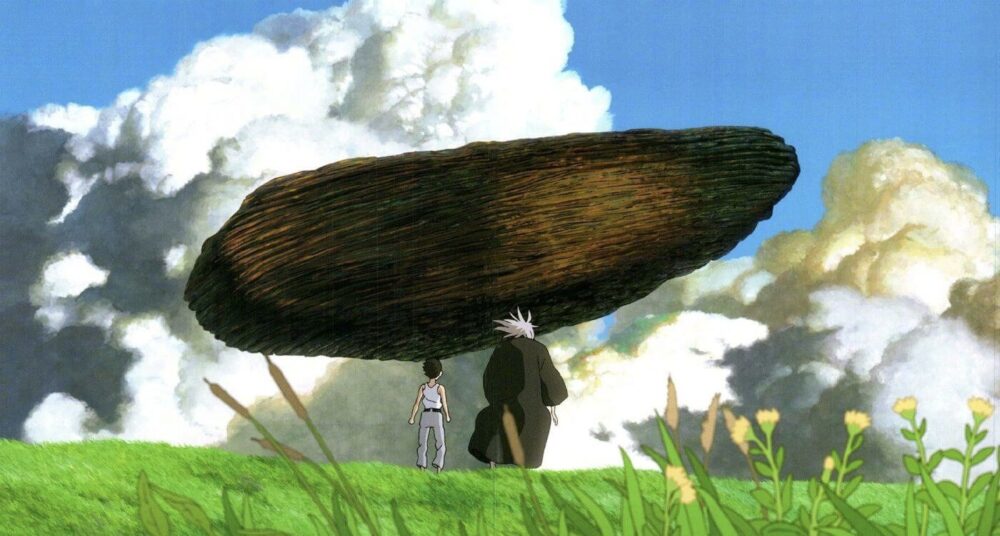

Like many Miyazaki movies, water represents the spirit realm that lies beneath the real world and is the source of our spiritual and intuitive artistic concepts of childhood. Stone is the medium through which humans can interact with the spirit world, both through building the things that we see in our intuitive and artistic spaces through creativity and architecture, and also, as Miyazaki never lets us forget, through death. Stone is what is erected over our bodies when we die as a tomb or gravestone, and the building blocks and stone toys in the movie are often referred to as being similar to gravestones.

This film is full of the post-industrial animism that Miyazaki loves to put into tension with the secular and scientific in his films. Many of the stones in the film are referenced as being alive or crackling with electricity. Often they look neolithic, carved into temples, inlaid with runes, or arranged as dolmens – the origin of architecture. Stone in the movie represents the human attempts to build constructs in the real world out of the unconscious. They are the bridge between the worlds. Stone is linked to humans’ attempts to bridge and control both realms; however, it is also associated with the hubris, grandiosity, and damage that can result from said attempt to exert control.

The “Lost World” of Artistic Intuition

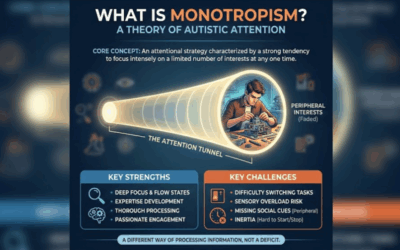

Miyazaki has said in interviews that the “lost world” he references, which lies under the surface of reality, is not nostalgia from lived experience because even children with no lived experience “remember.” Thinkers like Henri Corbin, Anthony Stevens, David Abram, and Erich Neumann have interacted with this same phenomenon.

Corbin coined the term mundus imaginalis to describe an intermediary realm between the physical and the divine, accessible through the imagination. This realm, he argued, is as real as the material world, and it is the source of all true art and spirituality.

Stevens has written about the collective unconscious as a repository of ancient, archetypal wisdom that we all share. This wisdom, he suggests, is rooted in our evolutionary history and our deep connection to the natural world. It manifests in the form of symbols, myths, and intuitive knowledge that can guide us towards wholeness and meaning.

Abram argues that the human capacity for language and symbolic thought emerged from our reciprocal relationship with the living landscape. For our ancestors, the world was alive with meaning and intelligence, and every rock, tree, and animal had a story to tell. Abram suggests that by reconnecting with this animistic perception, we can begin to heal the rift between ourselves and the more-than-human world.

Miyazaki is calling us back to a world that the modern world forgot when it individuated from the Edenic state that was nature and synthesis with nature. We all come from this place, and Miyazaki feels that the trick to art is the sincerity and integrity to hear the voices inherent in the living elements of stone, metal, water, fire, and spirit. Before we were conscious, these things spoke to us directly through archetypes, and Miyazaki wants to point us back to an enchanted world of art where they can speak again.

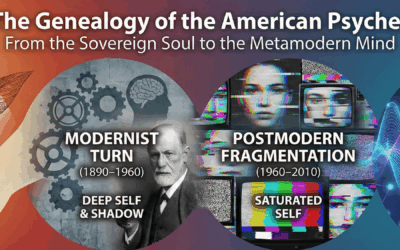

Archetypes, Embodiment, and the Artistic Mind

As Anthony Stevens argues in his book Archetype Revisited, archetypes can be seen as evolutionary adaptations, “inborn templates” of cognition and behavior that guided our ancestors in meeting the challenges of survival and reproduction. Neurologist Antonio Damasio, in his book Descartes’ Error, posits that reason and emotion are not separate but intimately intertwined in the brain. Our “gut feelings” and “somatic markers” – the visceral sensations that guide our decisions and valuations – are not just primitive impulses to be controlled by the intellect but essential sources of wisdom and intuition.

This “embodied” view of the mind is supported by research on the role of neurotransmitters, hormones, and other biochemicals in regulating mood, memory, and motivation. Oxytocin, for example, the so-called “cuddle hormone,” has been shown to promote pair-bonding, maternal care, and social trust – all behaviors that go beyond mere sexual gratification.

Similarly, the complex interplay of genetics, epigenetics, and the environment in shaping human behavior and development challenges the Freudian idea of the psyche as a fixed, universal structure. As evolutionary anthropologist Louise Barrett argues in her book Beyond the Brain, the mind is not a static product but a dynamic process that emerges from the interaction of the organism with its physical and social environment.

The human capacity for language, symbolism, and culture is not just a “veneer” over primal drives, as Freud sometimes suggested, but a radical evolutionary innovation that has transformed the very nature of our minds and bodies. The enlarged neocortex, the extended period of childhood dependency, the plasticity of the brain – all these adaptations point to the centrality of learning, socialization, and flexible behavior in human life.

The philosopher and ecologist David Abram, in his book The Spell of the Sensuous, goes even further in challenging the modern Western view of the mind as a disembodied, rational agent separate from nature. Drawing on the animistic worldviews of indigenous peoples, Abram argues that human consciousness is profoundly shaped by our sensory engagement with the living landscape.

These perspectives are highly relevant to understanding the role of intuition, art, and cultural trauma in Miyazaki’s work and life. They suggest that the creative process is not just a matter of intellectual problem-solving but a embodied sincerity and emotionally resonant engagement with the world. By tapping into the wellspring of archetypal imagery and the sensuous intelligence of the natural world, the artist can access a profound source of meaning and healing.

Miyazaki’s Pact with the Stone

Miyazaki presents artistry as a kind of pact made with the “stone,” a living entity that has fallen from the heavens. This stone bestows thirteen creative tools, represented by stone blocks, which allow the artist to shape the world. But this pact comes with a price – the artist must grapple with their own perfectionism, the limitations of mortality, and the difficulty of pleasing others while staying true to their vision.

The film suggests that each of us must find our own relationship to the burden and ecstasy of the creative process. Aspiring to a perfect, eternal tower may be a noble pursuit, but in the end, we can only work with the time and tools allotted to us. What matters is picking up the blocks, however few or flawed, and having the courage to build.

This idea of a creative pact with the living world is a powerful metaphor for the role of the artist in Miyazaki’s vision. The artist, like the shaman or the mystic, is a mediator between the human and more-than-human realms, a conduit for the creative energy that flows through all things. But this role comes with great responsibility and the ever-present risk of losing oneself in the pursuit of perfection or the desire for recognition.

In the end, Miyazaki suggests, the true test of the artist is not in the grandeur of their creation, but in the sincerity and integrity with which they approach the act of creation itself. It is in the willingness to listen to the whispers of the stone, to honor the living spirit in all things, and to create from a place of compassion and reverence for the world.

Consumerism in the Artistic Space

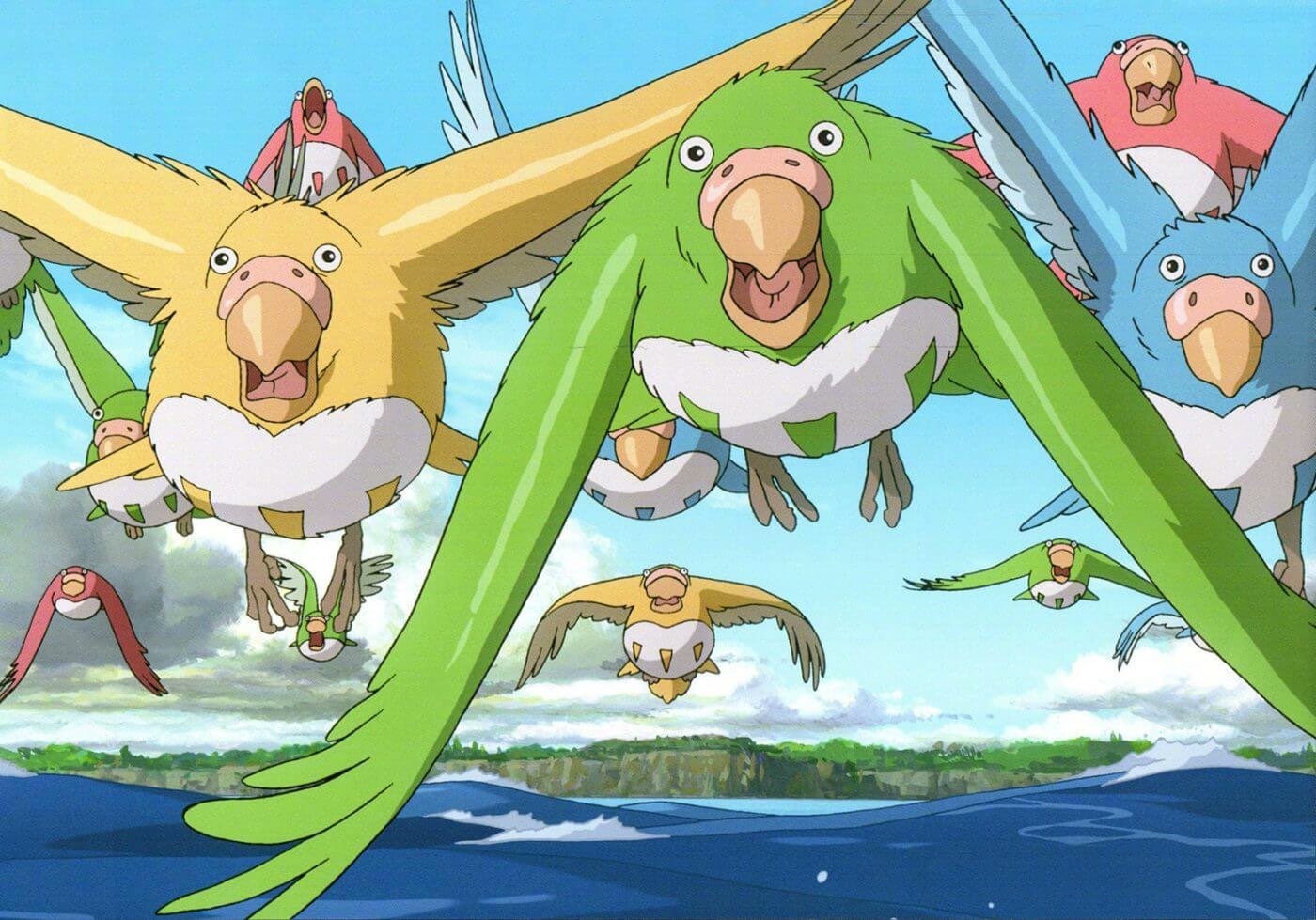

While the most of the film is a complex and extended metaphor, there are some relatively dirrect references that are hard to unse. The parakeets represent the voracious needs of the audience to consume new content without discrimination or a desire to grow. They are dangerous, willing to eat bread and fruit or the living flesh of the artist without any distinction. The parakeets cannot tell the difference between the Kardashians and Citizen Kane, American cheese or filet mignon. Outside of the tower, they become simple, dumb animals again, pooping on the characters but also pretty birds that are somewhat beutifull part of nature.

For Miyazaki, there is no good or evil, like everything else he sees inevitable natural forces that should be balanced and have their tensions maintained, much like the world of the artist. The parakeets’ behavior within the tower can be seen as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked consumption and the commodification of art. When audiences become too ravenous, too focused on devouring content without appreciation for its deeper meaning or the effort that goes into its creation, they risk destroying the very thing they crave. The artist, in turn, must find ways to satiate this hunger while preserving their own integrity and the essence of their work.

The parakets may be a metaphor for the bird or reptile part of the triune brain that is so connected to our early ancestory as animals it has lost humaninty. They are the saddest charachters in the film, cut off from both the human and the spirit world. Yet, the parakeets’ transformation outside the tower also suggests that this hunger for new novel content is not inherently malicious. It is a natural impulse, one that can be harnessed and directed towards more meaningful engagement. We can synthesize the spiritual and the human if we want too. Our animal nature defines us when we do not choose eiither for the right reasons.

Self-Reference and Extended Metaphor

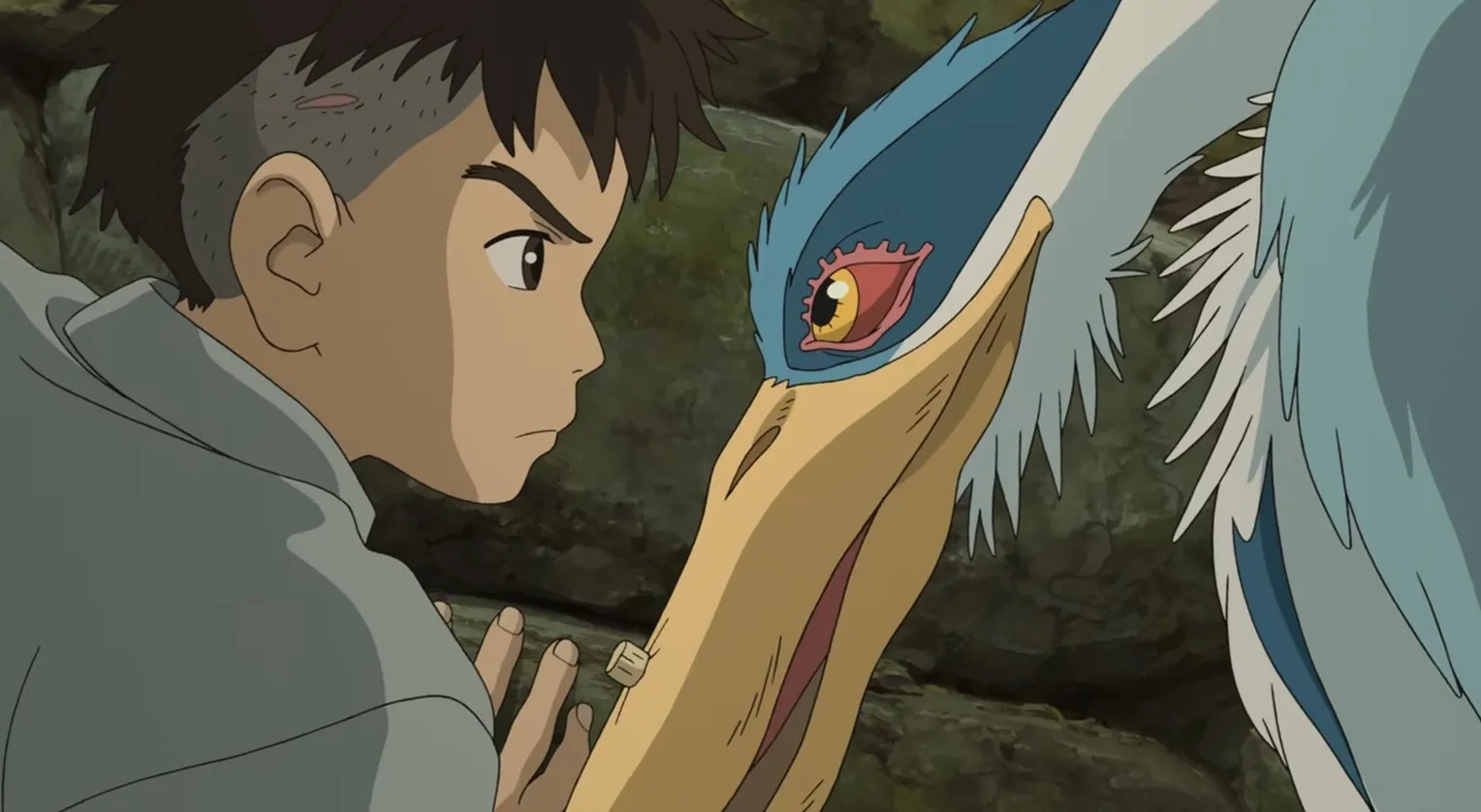

Many Ghibli staff have spoken about the personal influences that Miyazaki puts into the film about his childhood life and the people in his filmmaking process. His producer Toshio Suzuki has spoken saying that he believes that he is portrayed, sometimes unflatteringly, by Miyazaki as the titular heron. As the producer and “realist” in the creative space, the producer has to translate and more often compromise the artistic vision into what can actually be made and mass-produced. The titular boy first sees the heron introducing him to the world of the magical that might also be the endless possibilities of animation. The Heron (producer) recognizes ability but also seeks to control and manipulate it to make the compromises that make it shareable with others by carving off pieces of the unrealistic but beautiful infinite possibilities all art has. At first, the heron threatens the boy, but the boy has fletched his arrows with magical feathers, perhaps like a talented writer’s or animator’s quill, that are so swift that they cannot be coopted or controlled. By the end, they have an uneasy allegiance.

The mentor animator Isao Takahata was supposed to be the focus of the film through his stand-in, the Grand Uncle, but his death meant the focus of the film shifted to the relationship between the boy and the heron. After finishing the movie, you may feel like you watched two movies spliced together. And you did, in that the movie sets up a very different conversation than it ultimately has the ability to have. This change in the expected and the outcome may be part of the point the final film is trying to make.

In the real-world context around Studio Ghibli, Miyazaki was never able to find a successor for his studio. His son has spoken out about his resentment at the animation industry, and Miyazaki has been quietly critical of his son Goro’s output. No successor for his studio has been found. Miazaki prepared to make a movie very personla movie about his relationship with his animator world-builder friend and mentor, and then halfway through the film, this person died. What might have started as a love letter to his collaborators and mentors had to become an honest reflection on what the role of art is in the culture of mass production and the relationships that define that system. Not only this but also with in the temporal relationships of the possible.

I do not think that there is one interpretation or one symbol for the world Miyazaki describes. The realities of the unconscious, has images that are notoriously self-reflexive and kaleidoscopic. It is no coincidence that there are visual allusions to almost all of Miyazaki’s works in the world that by the end we can falling apart. Clearly, this film is a reflection on his body of work, its role in the culture, and the relationships and compromises Miyazaki had to make to create the art.

The artistic unconscious Eden state that exists within the tower is a timeless. Anyone can be encountered at any point in their life, and all times and artistic visions are intertwined in a chreative anarchy with its own harmony. It represents a place that is perfect but also impossible. The boy protagonist can meet his mother at his own age, but without letting go of her and returning her to her own time, he will not exist. Without returning to his own life, he himself will never really get to live.

The boy ultimately rejects the Grand Uncle’s magical powers of the 13 blocks and the project of fixing or carrying on the greater project. Miyazaki, a notorious perfectionist, is maybe accepting some kind of limitations here. The boy leaves holding only one block uncorrupted by the malice.

The Grand Uncle’s resemblance to Friedrich Nietzsche is probably no accident. Some thinkers have such a profound world-breaking effect on the arts that their legacy is in the response of new legacies that they creates but are too singular a vision to be carried on in any direct sense. These geniuses become reference points for other creative legacies and cannot be ignored even by their detractors.

Returning to the neolithic symbolism, the ultimate pact that gave the Grand Uncle artist his creative power comes from a sentient, perhaps omniscient, alien stone that fell from heaven to the base of the tower. It gave him 13 stone blocks as artistic tools that let him play god in the creative world but may slowly have become corrupted with the forces they have needed to interact with. It can be interacted with by carving, shaping, and stacking magical stones. The Grand Uncle wants to give the boy the chance to inherit this pact, but it is not something that the boy is willing or able to do. This breaks the imperfect world of the old artist, and he will never see it perfected or finished. But the point may be that we never can.

The pact we make with the stone as artists is our relationship to death itself. It means that we have to decide if we will be so perfectionistic that our art can never be mass-produced or known. It becomes how much of our own legacy we think the next generation can or should carry on and how much of our own identity we put into our artistic legacy. It is the realization that often there are great artists who can be conversed with through history but not singularly understood and may have no direct symbolic or artistic descendants. Our pact with the stone is our own relationship to the limitations of life, godhood, and the burden of the artistic genius.

Even in the film, the symbols for Miyazaki may not be Miyazaki himself. Instead, Miyazaki is seeing himself as a kind of archetype or his life’s journey as a kind of archetypal struggle. He is coming to terms with the inevitabilities that move the inner and outter worlds. In his worldview, there are only forces out of balance, not good or evil. Just like our unconscious and in our dreams, the symbols we use for ourselves are also symbols for our children and our gods.

The boy is definitely a stand-in for Miyazaki from one perspective but also maybe his son, who he is freeing from the burden of having a life run by dreams; his grandson, to whom he may be saying goodbye; his mentor, whose mantle he is refusing politely; and his own legacy that he may be symbolically externalizing to come to terms with.

Thie film is a meditation on the co-mingling of Miazaki’s biographical past and future but also the myths and expectations around him. It is a meditaion on the capitalist societies relationship to the artistic drives and the moderating and limiting forces one must reckon with to create that art. Some of these tensions are through the communities of people we need ti create somethingn like a move and some of them are abouut the limitations of the human and our place in history.

It is also an invitation for the next generation to pick up the blocks, even if they have to start with one block uncorrupted with malice instead of a tower made of a set of 13 that has had to make some compromises.

In The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki presents two contrasting father figures: Mahito’s father, the practical entrepreneur of the outer world, and the Grand Uncle, the twisted, godlike genius of the inner world. Despite their differences, both men share a common goal – to make a better world. Mahito’s father pursues this aim through his post-war work in design and manufacturing, while the Grand Uncle attempts to shape reality itself through his mastery of the magical realm.

The film suggests that the key to making a better world lies in the sincerity with which we approach our work and our creativity. Mahito, as the young protagonist, must navigate the tensions between these two worlds and find his own path forward. In rejecting the Grand Uncle’s offer of the 13 blocks and the burden of perfection they represent, Mahito chooses to start anew with a single, uncorrupted block. A choice reflecting Miyazaki’s faith that the next generation will commit to authenticity and integrity in the face of the compromises and corruptions that can come with the pursuit of art, influence and creative recognition and expresion.

More on the Metaphor in Miyazaki

This is a great video by Densetsu Media further exploring the influences and themes in the film

Filmography

- Castle in the Sky (1986)

- My Neighbor Totoro (1988)

- Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989)

- Porco Rosso (1992)

- Princess Mononoke (1997)

- Spirited Away (2001)

- Howl’s Moving Castle (2004)

- Ponyo (2008)

- The Wind Rises (2013)

- The Boy and the Heron (2023)

Further Reading

- Cavallaro, D. (2006). The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki. McFarland & Company.

- Napier, S. J. (2005). Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Odell, C., & Le Blanc, M. (2009). Studio Ghibli: The Films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. Kamera Books.

- Yamanaka, H. (2008). The Utopian “Power to Live”: The Significance of the Miyazaki Phenomenon. In M. W. MacWilliams (Ed.), Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime (pp. 237-255). M.E. Sharpe.

- McCarthy, H. (1999). Hayao Miyazaki: Master of Japanese Animation. Stone Bridge Press.

- Miyazaki, H. (2009). Turning Point: 1997-2008. VIZ Media LLC.

- Kaplan, D. E. (2019). The Animistic Imagination: Animism, Metaphor, and Meaning-Making in Animation. Animation Studies, 14.

- Schodt, F. L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Stone Bridge Press.

- Lamarre, T. (2009). The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation. University of Minnesota Press.

- Yoshioka, S. (2018). Toshio Suzuki and Studio Ghibli: The Producer as Auteur. Palgrave Macmillan.

0 Comments