The Empty Tomb:

The Cave Beneath

Drive up Highway 31 in Vestavia Hills, Alabama, and you’ll pass beneath a curious monument: a miniature Roman temple perched on a promontory, watching over the traffic like a displaced deity. This is the Sibyl Temple, the city’s official logo, its secular icon, its proud gateway. What most drivers don’t know is that this structure was designed as a tomb. Specifically, George B. Ward’s tomb, complete with a cave excavated beneath for his body.

He never made it in. Jefferson County law wouldn’t allow it.

This empty tomb, this monument to thwarted ambition, has become the perfect symbol for a city that embodies one of America’s most potent psychological contradictions: a community that promises transcendence through achievement while slowly suffocating under the weight of its own expectations. To understand how we got here, how a pagan dreamer’s mountain paradise became a pressure cooker suburb where teenagers break under the strain of perfection, we need to excavate not just the history, but the psyche of both the man and the moment that created this peculiar American tragedy.

The Man Before the Mountain

George Battey Ward was born March 1, 1867, in Atlanta, Georgia, but arrived in Birmingham shortly after its founding in 1871. His parents, George R. and Margaret Ward, operated the Relay House hotel along with his grandparents William and Jane Ketchum. Ward’s mother hosted many social events at the hotel and was one of the founding members of the Episcopal Church of the Advent, establishing from the beginning Ward’s connection to Birmingham’s social and religious elite.

Ward attended the Powell School until he was sixteen and took a job as a runner for Charles Linn’s National Bank of Birmingham. The young Ward narrowly missed death when a bullet was fired into a mob rushing the Jefferson County Courthouse to lynch murderer Richard Hawes on December 8, 1888, an early encounter with the violence that characterized Birmingham’s rough early years. That same year, Ward enrolled in prep school at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee, seeking the education that would elevate him beyond his banking runner status. When he returned to Birmingham, his education paid off with promotions that eventually led to the position of paying teller.

In 1899, he campaigned successfully for a seat on the Birmingham Board of Aldermen, but resigned after a few months to manage a bank in Sheffield, revealing early the pattern of restlessness that would characterize his career. In 1900, Ward returned to the National Bank of Birmingham, but left after only a year to form a new investment company with John M. Caldwell. This entrepreneurial venture would provide the foundation for his later wealth through Ward, Sterne & Company, though the specific nature of his investments remains less documented than his later eccentricities. He ran again for the Board of Aldermen in the 1901 election, defeating Christian Rambow for a four-year term representing Ward 2 of the city, beginning his serious political career.

Mayor of Birmingham and the City Beautiful

Ward ran against incumbent Mel Drennen in the 1903 Birmingham mayoral election but lost. When Drennen retired, Ward ran again, this time against four opponents, of which the strongest was Drennen protege Charles S. Simmons. Ward won the most votes in the primary, but avoided a run-off when Simmons withdrew from the race. He was inaugurated on May 4, 1905, for a two-year term that would transform Birmingham’s physical landscape and civic culture.

During his first term, Ward surprised many by taking charge personally of the details of governing. Accused of running the city as a one-man show, he responded with characteristic bluntness: “Why not, when I know best?” This attitude, simultaneously progressive and autocratic, would define his approach to governance. In the 1907 Birmingham mayoral election, Ward faced Frank P. O’Brien for the first time. Although O’Brien promised to improve the undermanned Birmingham Police Department, Ward narrowly won re-election, in part by identifying O’Brien as a puppet of liquor and gambling interests, demonstrating his ability to navigate Birmingham’s complex political landscape.

Ward’s mayoral achievements were substantial and transformative. He codified and published the Birmingham Municipal Code for the first time, bringing order to a chaotic system of laws and regulations. Understanding that law meant nothing without public knowledge, he mailed a copy of the city’s sanitation laws to every household. He established the position of City Comptroller and reported the city’s financial balance to the press each month, bringing unprecedented transparency to city finances. He created several departments, including one responsible for building inspections, modernizing Birmingham’s administrative structure. He enlarged the police department and upgraded firefighting equipment, addressing public safety in a city prone to both crime and fires. He invested heavily in sewer construction and worked tirelessly to help the Birmingham City Schools keep pace with the rapidly growing student population.

But Ward’s most lasting contribution was his aesthetic vision for Birmingham. He urged utilities to bury their services underground, removing the web of wires that cluttered the skyline. He instituted city-wide clean-up days to beautify downtown, mobilizing citizens in collective action. Most significantly, he oversaw an enormous expansion of dedicated public park land, including the purchase of 100 acres at Green Springs, which is now known as George Ward Park. In a gesture that revealed his democratic approach to public space, he had signs warning people to “Keep Off the Grass” removed to encourage public use of parks, believing that beauty should be accessible to all.

Ward was known for his strict enforcement of saloon regulations, which he considered a better alternative than strict prohibition, revealing a pragmatic approach to moral legislation. Nevertheless, he became a leader in campaigning for the 1907 referendum which established local prohibition in Jefferson County, demonstrating his ability to read political winds and adapt accordingly.

His 1908 pamphlet, “Compliments of G. Ward,” preserved in the Birmingham Public Library archives, reveals the mind of an energetic micromanager with an almost obsessive belief in the power of aesthetic intervention. “Paint your house,” he commanded. “If you cannot paint it, whitewash it. If you cannot whitewash all of it, whitewash the fence. Clean up the yard. Burn up the rubbish. Haul off the old cans.” He organized “block improvement societies” and personally inspected neighborhoods, handing out prizes for the best-kept yards. This wasn’t mere governance; it was an attempt to impose order on chaos through sheer force of will, a belief that if you could just get the whitewash on enough fences and plant enough greenery, you could elevate the human spirit itself.

The Constitutional Crisis and Commission Presidency

In 1907, the Alabama legislature passed a new municipal code which changed the balance of power in city government. Previously, the mayor held one vote in meetings of the Board of Aldermen and made all committee appointments. The new law separated legislative and executive powers, giving the mayor only veto power over the Board while increasing his power to hire and fire city workers. This restructuring would precipitate a constitutional crisis that revealed the fragility of Birmingham’s democratic institutions.

In August 1907, while Ward was on a six-week tour of Europe, presumably studying the classical architecture and civic planning that would later influence Vestavia, the Board of Aldermen voted 10-7 to reorganize as a City Council with John L. Parker as President and Acting Mayor. Parker immediately re-assigned all the committees, leaving Ward’s supporters primarily in charge of cemetery issues, a deliberate insult that relegated them to the least significant governmental function.

With the support of the Birmingham Police Department, Ward opted to ignore the Board’s actions. He called a meeting of the “Board of Aldermen” and refused to allow Council members to take seats as officers of the city. Parker filed suit against Ward, and won a judgment from the Alabama Supreme Court giving the Council control of the city. The anti-Ward faction’s main goal of loosening restrictions on saloons, however, was pre-empted by the popular election for prohibition which took effect at the same time, a pyrrhic victory that demonstrated Ward’s continued influence even in defeat.

In 1910, Ward decided to run for Sheriff of Jefferson County, a position that was arguably more powerful than mayor in Alabama’s political structure. He spent a great deal of money on his campaign and expected a victory based on polls taken in advance of the election, but ended up losing badly to Walter McAdory. After the election, Ward announced that he would never return to politics, a promise he would soon break.

Nevertheless, the progressive movement in Birmingham politics which had reached a peak in 1910 enticed him back, and he decided to make a run for President of the new Birmingham City Commission in 1913. The first commission had been appointed by Governor B. B. Comer. In the race for the second commission’s presidency, Ward squared off against labor candidate Clement Wood, winning easily. He took the oath of office on November 13, 1913, beginning what would be his final and most frustrating political chapter.

Ward’s primary task as Commission President was to lobby to secure additional municipal revenues. He proclaimed that Birmingham’s low tax collections placed it alone at the very bottom of the 38 American cities with populations of 100,000 to 300,000. In order to make up the difference, Birmingham’s business license fees were among the highest in the country. In anticipation of being absorbed into Greater Birmingham, many formerly-independent cities had undertaken large public works projects which were folded into Birmingham’s debt, then over $600,000 and growing by $1,000 a day.

Departmental budgets were repeatedly tightened while broad subcommittees explored options for improving municipal finances. The city’s recreation and welfare departments closed. Students in city schools were charged fees. Police and fire department personnel were reduced by a third, and the Birmingham Zoo was closed down. These austerity measures revealed the limits of Ward’s progressive vision when confronted with fiscal reality.

The Alabama legislature only grudgingly prepared a bill for referendum that would allow Birmingham to increase its municipal income tax rate from 1% to 1.5%. The measure failed in referendum in 1915, a devastating blow to Ward’s plans for civic improvement. In the face of the city’s financial incapacity, Ward mounted an aggressive public relations campaign to beautify the city through citizen-led action. The department of public works assisted citizen-led drives to tend vacant lots and plant gardens. Ward’s City Beautiful movement attracted the attention of the national press, with journalists marveling at Birmingham’s transformation despite its poverty. The cooperation of the local press helped preserve Ward’s reputation despite the city’s precarious financial situation.

The Final Defeat and Psychological Transformation

Frustrated by his inability to secure adequate revenues, Ward announced he would not run for re-election in 1917. However, he changed his mind and decided to run after all, a decision that would prove politically fatal. His opponent was Nathaniel Barrett, a physician who was endorsed by the “True Americans,” an anti-immigration, racist, and anti-Catholic political organization that had gained prominence in association with the Guardians of Liberty.

The True Americans were particularly active in Birmingham, where “nativists,” as they came to be called, virtually controlled local elections in the late 1910s. They were characterized by their strong opposition to immigration, particularly from Catholic countries, and their efforts to maintain what they viewed as the purity of American society. Barrett, a Baptist, had been a leader in the campaign to prohibit the showing of movies on Sundays and labeled Ward, an Episcopalian, as a “tool of the Catholics” during the 1917 election campaign. Barrett was a member of several fraternal organizations, including the Knights Templar, the Shrine, Knights of Pythias, and the Junior Order of United American Mechanics, organizations that provided the social and political infrastructure for nativist politics.

Ward’s popularity carried him in the central city, where his progressive reforms had improved life for working-class residents, but the annexed suburbs overwhelmingly supported Barrett, revealing the geographic and class divisions that would continue to characterize Birmingham politics. Ward left politics for the last time, but not before one final gesture of defiance.

During President Warren Harding’s 1921 visit to Birmingham, Ward rode alongside African American barber Frank McQueen in the lead car, representing the “Pioneers of 1871” who had lived in the city since its founding. This gesture, in the context of 1920s Alabama, was remarkably progressive and demonstrated Ward’s continued willingness to challenge social conventions even after his political career had ended. It was also, perhaps, a final rebuke to the nativist forces that had driven him from office.

This defeat marked a critical psychological pivot. Having been rejected by the public sphere, Ward, the visionary controller, did not abandon his vision. He simply transferred it. He retreated from the city and ascended Shades Mountain to build a private “City Beautiful,” a personal kingdom where his aesthetic and social vision could be implemented without the messy compromises of democracy.

The Creation of Vestavia

In 1923, Ward purchased a 20-acre parcel of land on the ridge of Shades Mountain. His inspiration came from a souvenir model he had purchased during a 1907 trip to Italy, a trip that occurred during his mayoral tenure when he was presumably studying European civic planning and architecture. The model was of what was then called a “Temple of Vesta,” later believed to have been built to honor Ceres, but now known as the Temple of Hercules Victor. The original temple was a peripteros-style structure constructed in the 2nd century B.C. in the Forum Boarium in Rome. Like that temple, Ward’s “Vestavia” would consist of a cylindrical building with twenty columns encircling it, though Ward’s model would have been a speculative reconstruction of the original Roman temple, filtered through Renaissance and Enlightenment imagination.

Ward commissioned architect William Leslie Welton to design the structure, beginning a collaboration that would produce one of the most unusual residential structures in American architectural history. Having made the decision to use “the rich vari-colored ores of his native mountains” instead of marble, Welton simplified the decorative scheme of the original. As Ward put it, “I was compelled to drift toward the simplicity of the Doric, and forego the more attractive Ionic columns with their exquisite detail.” This compromise between classical idealism and Alabama materialism would characterize the entire project.

The documented specifications were impressive and reveal the scale of Ward’s ambition. The columns were 32 inches in diameter at the base and 28 feet tall, proportions more suited to the Corinthian order than the Doric, revealing the tension between Ward’s classical aspirations and practical limitations. The entablature was 60 feet in diameter, incorporating molded medallions and garlands of flowers and fruits of a style popular for 18th century interiors, a baroque touch that would have horrified classical purists. The portico was 14 feet wide from the outer edge to the wall, providing a circular promenade around the entire structure. The walls were constructed of uncoursed sandstone, 2 feet thick at the base, with the chimney flue for the massive fireplace concealed inside, combining ancient aesthetics with modern convenience.

The interior on the main floor was an undivided circular space 28 feet across which Ward used as a living room and library, a democratic space that rejected the compartmentalization of Victorian domestic architecture. The walls were washed to a soft gray color with numerous niches for sculpture, creating a gallery effect. The windows were draped with gold scrims in summer and red velvet in winter, seasonal changes that echoed ancient Roman practice. The bookcases, in an unusual architectural feature, were hung from the ceiling on stout metal chains, creating a sense of floating knowledge.

A circular wrought iron staircase accessed Ward’s bedroom suite above, with a small bath and closet concealed behind partitions. Clerestory windows in a raised part of the attic roof provided natural light. Ward decorated the curving wall with postcard reproductions of paintings from the Louvre, a middle-class touch that revealed the democratic nature of his classical obsession. The lower floor was part basement and partly open to the gardens. It contained a large semi-circular dining room with room for 42 seats, a guest suite, kitchen, pantries, servants’ quarters, and garage, combining classical entertainment space with modern service requirements.

The Gardens and Grounds

Ward’s gardens were as elaborate as his house, perhaps more so, representing his attempt to recreate not just Roman architecture but an entire Roman landscape in Alabama. The upper 10 acres next to the house featured sculpted topiary hedges that required constant maintenance in Alabama’s climate. Statuary was placed throughout the grounds, creating encounters with classical figures at every turn. Most famously, he built miniature temple-style houses for three dogs on the property, including one called “Villa Cleopatra” that featured actual columns and decorative elements, treating his pets as Roman citizens deserving of architectural dignity.

A large reflecting pool, stocked with goldfish, was contained within low stone walls which hid green and blue subsurface lights, creating ethereal effects at night. A tiered fountain featured built-in planters for ferns and flowering vines, combining water features with botanical display. Near the entrance to the grounds Ward had built a raised dais with a large bronze bowl on a pedestal flanking a throne-like stone chair from which he could survey his domain, a touch that revealed the imperial nature of his self-conception.

The sunken garden was accessed by a path lined with hedges and sculpted pedestals bearing portrait statues, including Caesar, Virgil, Sappho, Chronos, Nidia and Glaucus, a pantheon that mixed historical figures with fictional characters from Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novel “The Last Days of Pompeii.” These alternated with rose-colored garden lights that created a theatrical pathway. Numerous metal trellises in the shape of scallop shells supported different breeds of rose. A broad pool was planted with Egyptian lotus, introducing African flora to the Roman landscape. Another well-shaded pool featured a large statue of Vesta poised on a boulder while emptying two large water pitchers, the goddess herself presiding over the waters.

The gardens continued through what Ward called a “mystic maze,” though what made it mystic remains undocumented, to muscadine arbors that were one of the few successful agricultural experiments on the estate. Beyond lay fruit orchards and a field of clover, practical spaces that provided food for the table while maintaining the estate’s pastoral character. The estate was reached by a driveway paved with crushed white limestone that gleamed in moonlight, secured behind a massive wrought iron gate flanked by stone piers topped with planters. The remaining lower 10 acres below the access road were left in a “rustic” condition with a few winding pathways, a romantic wilderness that contrasted with the formal gardens above.

Ward’s most documented experiment was his importation of Italian elements in an attempt to recreate authentic Roman agriculture. He imported Italian cypress trees, most of which died in Alabama’s humidity, a failure he refused to accept. He brought in grapevines from Italy for what he called a “vineyard of Bacchus” that never quite took to the Alabama soil but which he maintained stubbornly year after year. Most remarkably, he imported actual Italian soil, shipped across the Atlantic at considerable expense, because he believed Alabama dirt wasn’t classical enough for his Roman vines. The vines died, of course. Alabama humidity and Italian grapes were never going to be compatible. But Ward replanted them, year after year, in what can only be described as horticultural madness or admirable stubbornness, depending on your perspective.

The Sibyl Temple and Death’s Architecture

In 1929, at the height of his powers and just before the Great Depression would begin eating away at his fortune, Ward commissioned the Sibyl Temple. Designed by the firm of Miller and Martin and completed that year, this structure was smaller than the main residence but in many ways more psychologically revealing. While the Temple of Vesta was about life, hearth, and home, the Temple of Sibyl was always about death.

The temple was a monopteros, a circular temple without walls, built of steel-reinforced concrete that was originally painted a muted rose color. Eight fluted columns, 16 feet tall, supported a dome weighing 63 tons. The design showed multiple influences: the siting was probably inspired by the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, sometimes associated with the Tiburtine Sibyl, which overlooks a dramatic gorge. The domed roof may have been inspired by speculative reconstructions of circular temples. The capitals resembled those on the Roman “Tower of the Winds” in Athens, mixing Greek and Roman elements in typical neoclassical fashion.

But the real significance lay underground. Ward had excavated a cave beneath the temple, accessed by a hidden entrance disguised as a decorative garden feature. This cave was to be his tomb, and he spent considerable time and money making it suitable for eternal habitation. The vault was constructed into the foundations, creating a permanent sepulcher. Ward’s will specified his desire to be buried in this tomb, dressed in appropriate classical garments, maintaining his Roman identity even in death.

When Ward died on September 11, 1940, the tragic irony of his carefully planned afterlife became apparent. Jefferson County law prevented burial outside of designated cemeteries. The man who had been Birmingham’s mayor, who had shaped its parks and civic spaces, who had retreated to build his own private paradise, was denied his final wish by the very governmental structures he had once controlled. Ward was interred at Elmwood Cemetery instead, just another citizen in a conventional grave, his elaborate tomb forever empty.

Life at Vestavia

The documented events at Vestavia reveal a carefully orchestrated performance that continued for nearly two decades. Ward hosted an annual dinner for Latin students from Ramsay High School, using his estate as an educational stage for classical learning. He held a “Blossomtime Festival” with area pageant queens, combining classical aesthetics with Southern belle culture. Regular piano concerts and listening parties featured his automatic Victrola VE 10-50 record changer, one of the most advanced audio systems of its time.

Notable guests included George Washington Carver, the famous botanist who presumably would have been interested in Ward’s agricultural experiments. Better Homes and Gardens editor Elmer Peterson visited, possibly to document the gardens for national publication. Most remarkably, Arnaldo Mussolini, brother of the Italian dictator, visited the estate, creating an awkward connection between Ward’s Roman fantasies and the fascist appropriation of Roman imagery.

The Roman theme permeated every aspect of estate life. Servants were not just dressed as Roman soldiers but were given Roman names that replaced their actual identities. The cook became Lucullus, named after the famous Roman general known for his lavish banquets. The chauffeur was renamed Cataline, after the Roman conspirator. The gardeners became Pompey and Marcellus, names that carried their own historical weight. These servants were required to stay in character, creating a total theatrical environment. Ward paid triple the going rate for domestic service but demanded absolute participation in his Roman fantasy, creating a peculiar economy of performance.

The estate’s lighting system was equally theatrical. A green beacon announced when Ward was receiving guests, a red light indicated the gates were closed, and white lights shone during private parties. Extensive garden lighting created what observers called a “constellation” visible from the valley below. The Alabama Powergram noted that Ward was “the largest rural electrical customer in the state,” a distinction that revealed the scale of his illuminated fantasy.

The loudspeaker system Ward installed in 1931 was one of the first residential public address systems in Alabama. Every Sunday afternoon, Ward played classical music, particularly Wagner and Verdi, transforming the mountain into an open-air concert hall. He used the system for traffic direction on busy weekends, acting as a self-appointed traffic controller on the mountain roads. Most famously, he maintained a network of informants among local mothers and would broadcast curfew reminders to specific teenagers. “Johnny Jones! Your mother says to come home!” became a regular feature of Saturday nights on Shades Mountain. In his final years, Ward used the system to deliver impromptu lectures about the birds he observed, consistent with his role as founder and president of the Alabama Audubon Society from 1927 until his death.

The Decline and Transformation

By 1935, Ward’s fortune had declined due to the Great Depression and his health was failing. He was diagnosed with terminal throat cancer and suffered a stroke. His brokerage business, Ward, Sterne & Company, experienced significant decline during this period. The elaborate parties became less frequent, the gardens began to show signs of neglect, and the classical fantasy began to fray at the edges.

Ward died on September 11, 1940. A codicil to his will, dated April 13, 1940, stipulated that the house and upper 10 acres would pass to his nieces, and the lower 10 acres, including the Sibyl Temple, would be given to Jefferson County or the city of Birmingham as a public park. However, because his debts exceeded his assets, the executors listed both properties for sale for about $30,000. The estate that had cost hundreds of thousands to build and maintain was reduced to a distressed property.

The estate went unsold for several years and fell into disrepair. Without Ward’s obsessive maintenance, the gardens became overgrown, the pools filled with debris, and the buildings began to deteriorate. Nature began reclaiming what Ward had carved from the mountain, with kudzu beginning its slow consumption of the abandoned structures.

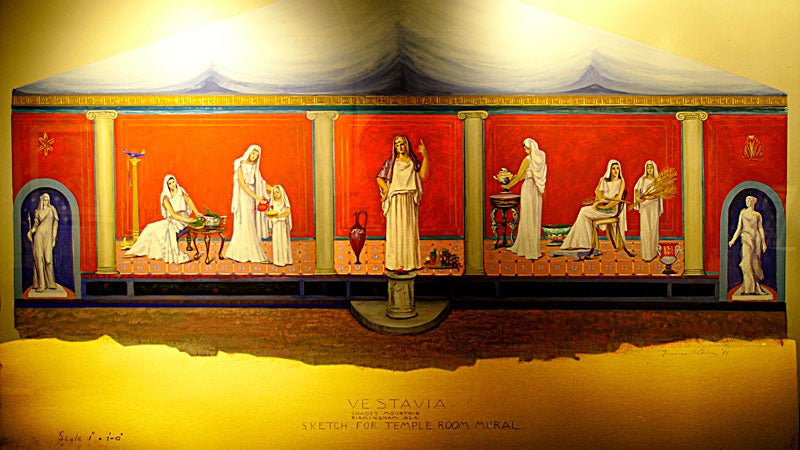

In 1947, developer Charles Byrd purchased the estate and transformed it into a tourist attraction called the “Vestavia Roman Rooms.” Byrd hired renowned church architect and decorator Viggo F. E. Rambusch to assist local architect Charles Snook with restoration plans in 1948. The upstairs bedroom was remade into a recreated “altar room” with new interior murals to match the artwork found in the Roman original. Young socialites posed for robe-clad figures in an 88-foot by 13-foot mural executed by Frances O’Brien, transforming Ward’s private space into public spectacle.

A larger kitchen and banqueting room was added to the basement. The restaurant served steaks and seafood in the evenings, soups and sandwiches at lunch. Mrs. Ewing Steele’s orange rolls became famous there and later became a staple at The Club on Red Mountain. Patrons could bring their own wine bottles, paying a nominal corkage fee to circumvent lingering prohibition-era restrictions. During renovations, significant changes were made to the Sibyl Temple. A chandelier and benches were removed, beginning the process of stripping the temple of its mortuary purpose. In 1950, Robert Jemison gave Byrd eight marble columns salvaged from the People’s Bank, which were used to create a pergola that served as a backdrop for an outdoor stage, adding new classical elements that Ward never envisioned.

The suburban City of Vestavia Hills was incorporated in 1950, using a drawing of Ward’s estate on its official seal. The name “Vestavia Hills” was Byrd’s creation for his residential subdivision, directly borrowing from Ward’s estate to provide instant prestige to his development. The new suburb traded on Ward’s classical aspirations while embracing the conformity and exclusivity that Ward had rejected.

The Baptist Transformation and Demolition

On March 4, 1958, the newly-formed Vestavia Hills Baptist Church purchased the property and moved its worship services from Vestavia City Hall to the former banqueting room. The congregation raised the old dance floor for the pulpit and installed the choir in the former bandstand. A former hothouse was converted into a baptistry and former storage and utility rooms were enlarged into nurseries. The original rooms of the house and the gatehouse were used for Sunday School classes and office space. Pastor John Wiley observed that his congregation was “repeating a pattern established by the early church, which made churches of former pagan temples in the Roman empire,” a historical parallel that would have amused or horrified Ward.

The church initially planned to preserve the structure. A late 1950s brochure stated, “We plan to erect a first building for our educational activities. Later we shall build a new sanctuary. The original structure shall be maintained for its beauty and historical association.” This promise would not be kept.

An $800,000 fund-raising campaign started in 1962, initially planning four new buildings around the temple. During the campaign, it was estimated that an additional $120,000 would be needed to relocate utilities and repair the 1925 structure. By 1968, faced with these costs, the church revised its building plan to include the removal of Ward’s former home. The church ran an advertisement in the Wall Street Journal offering the house as “free for the taking,” but received no legitimate offers.

Opposition to demolition came from multiple women’s organizations. The Women’s Civic Club of Birmingham, the Women’s Committee of 100, and the Women’s Chamber of Commerce joined in opposing the demolition plans and wrote and telephoned area leaders to plead for its preservation. The Alabama Historical Commission backed their efforts in 1969. These protests failed, however, and the congregation voted to proceed with demolition in 1970.

The actual demolition in April 1971 was both a spectacle and a liquidation. Statuary, kitchenwares and other trappings were sold at public auction which netted $2,971 for the building fund. The event was the public’s last opportunity to explore the deteriorating house. The demolition took three weeks. The twenty Doric columns, too massive to demolish conventionally, had to be toppled one by one using cables and bulldozers. Each falling column was witnessed by church members who saw it as progress toward their new sanctuary. The pink sandstone from the walls was crushed and used as fill for the new church’s parking lot. Ward’s temple literally became the foundation for Baptist station wagons.

The Sibyl Temple’s Preservation and Modern Vestavia Hills

The church donated the smaller Sibyl Temple to the Vestavia Hills Garden Club, which orchestrated its relocation in 1976. The move required closing roads and removing power lines to transport the 87-plus-ton structure. The temple was carefully relocated to its current position at Highway 31, where it serves as a gateway to the city. Significantly, the cave beneath, Ward’s intended tomb, was filled with concrete for “safety reasons,” the final denial of Ward’s burial wishes. The temple now serves as a symbol for the city of Vestavia Hills, marking the northern entrance while the main estate building still appears on the city’s official seal, though the building itself is long gone.

The transformation from Ward’s vision to modern Vestavia Hills represents a complete inversion of his original intention. Ward’s estate had been open to visitors of all races, though at different times, and represented a space of eccentric individualism and classical education. Modern Vestavia Hills became one of Alabama’s most exclusive suburbs, with a population that is overwhelmingly white and affluent. The city’s identity centers on its school system, established in 1970, just one year before Ward’s temple was demolished. Property values are directly tied to test scores, creating a different kind of performance pressure than Ward’s theatrical Roman fantasies.

Ward’s motto “A Life Above” originally referred to aesthetic and spiritual elevation, a rising above the mundane through beauty and classical culture. The modern city has transformed this into a focus on academic achievement and economic success. The school system has become what Ward’s sacred flame was meant to be: the thing that must be maintained at all costs, the guarantee of the community’s continuity and value.

Birmingham’s Pattern of Historic Loss

Ward’s temple wasn’t the only significant structure Birmingham lost during this era. The city has a documented pattern of demolishing historic structures that reveals a civic psychology unable to value its own history. Birmingham Terminal Station, a magnificent Byzantine-style structure designed by P. Thornton Marye that had served as the city’s gateway for sixty years, was demolished in 1969 despite a massive preservation campaign that drew national attention. Veterans returning from World War II had kissed the ground of this station. By 1969, the city decided that memory was worth less than parking spaces.

Ward’s Vestavia Temple was demolished just two years later in 1971, with notably less public outcry. The difference was telling: Terminal Station was public memory, shared by all of Birmingham’s citizens. Ward’s temple was private eccentricity, the fantasy of one man. The city had learned to mourn the loss of collective symbols but couldn’t see value in individual vision.

The pattern continued. The Milner Hotel, also known as the Sherrod Historic Railroad building, built in 1904, was demolished in 2009 for a parking lot that remains empty to this day. The Birmingham Southern Railroad Freight Depot, a handsome 1928 building, was demolished in 2014 for a redevelopment that never materialized. Between 1960 and 2020, Birmingham demolished over 200 structures listed as “historically significant” by various preservation groups. Of these, fewer than 20% were replaced with buildings of equal or greater architectural merit. The rest became parking lots, vacant lots, or generic commercial structures.

This pattern reveals more than poor urban planning. It reveals a civic psychology that cannot bear to look at its own reflection, that prefers parking lots to monuments because parking lots don’t remind you of anything. Birmingham’s economy has always been extractive, first iron and coal, now healthcare and banking. Extractive economies don’t value preservation; they value consumption. The logic of the mine and the furnace is to take what you need and leave a hole. This logic, internalized over generations, creates a civic psychology that sees destruction as progress, that cannot imagine value in what already exists.

Ward’s Lasting Influence

Despite the demolition of his main temple, Ward’s influence on Birmingham persists in several documented ways. He founded the Alabama Audubon Society in 1927 and served as its president for thirteen years until his death. His papers at the Birmingham Public Library, cataloged as AR12, include 24 volumes of scrapbooks detailing his career and local history, alongside extensive files on his personal interests in music, flowers, and birds. His correspondence includes letters with Margaret Mitchell, author of Gone with the Wind, who wrote to him seeking copies of his mother’s memoirs.

Ward’s approach to conservation was characteristically eccentric. He would dress in his Roman senator costume to deliver lectures about bird protection to skeptical Alabama farmers. He created what he called “bird sanctuary zones” on his estate, complete with miniature Roman temples as birdhouses built to exact scale with tiny columns, pediments, and even minute frescoes painted on interior walls that only the birds would see. While his methods were unusual, his practical conservation work was substantial. He personally funded the protection of over 1,000 acres of bird habitat and established three permanent sanctuaries that still exist today.

The land Ward designated as parks during his mayoral tenure eventually became part of Birmingham’s park system, including what is now George Ward Park. His influence on Birmingham’s garden culture, while harder to trace, can be seen in the city’s continued emphasis on public green spaces and the Birmingham Botanical Gardens, established in 1962 on land Ward had originally designated as a park.

Vesta’s Fire and Its Meaning

To understand George Ward’s life and legacy, we must understand why he chose Vesta as his patron goddess. Vesta was the ancient Roman goddess of the hearth, home, and family. She occupied a central place in Roman religion and culture because she represented the most fundamental human institution: the home. But Vesta was more than a domestic deity. She was the link between private and public life, between the family hearth and the civic flame.

In Roman culture, Vesta personified the hearth, which was the symbolic and literal center of domestic life. Every Roman household maintained a hearth in her honor. But beyond private worship, Vesta’s eternal fire in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum symbolized the security and continuity of the Roman state itself. The flame was tended by the Vestal Virgins, priestesses sworn to celibacy for 30 years, whose duties included maintaining the sacred fire, performing rituals, and safeguarding important wills and documents. If the eternal flame went out, it was considered a dire omen for the empire. The Romans celebrated Vesta through festivals like the Vestalia, held from June 7 to 15, during which the public could enter the inner sanctum of her temple and offer sacrifices.

Vesta’s fire symbolized the unity of home and state, linking private households to the broader Roman community. She represented chastity, loyalty, and continuity, values critical to Roman social and religious life. The goddess embodied the intersection of domestic, civic, and religious life, representing purity, domestic order, and stability, both for families and the city. Temples to Vesta, often circular to resemble the hearth, inspired architectural forms that Ward would later emulate in Alabama.

For Ward, a lifelong bachelor who never married, Vesta offered multiple layers of meaning. The celibate discipline of the Vestal Virgins mirrored his own unmarried state. The concept of sacred guardianship aligned with his view of himself as guardian of civic virtue and aesthetic standards. The eternal flame represented the continuity he sought to maintain despite political rejection. As a former mayor who believed in the City Beautiful movement, Ward understood Vesta’s dual nature as both domestic and civic goddess. The connection between private virtue and public good that Vesta represented aligned perfectly with his progressive vision of urban reform through aesthetic intervention.

His defeat by nativist forces made the idea of maintaining a sacred flame on private property particularly appealing. If the public sphere rejected his vision of beauty and order, he would maintain it privately, keeping the flame burning on his mountaintop regardless of democratic opinion. In Baptist-dominated Alabama, choosing a pagan goddess was itself an act of rebellion against the forces that had rejected him. The Roman rituals and toga parties were deliberate provocations against the “True Americans” who had labeled him a tool of foreign influences. Vesta represented a cosmopolitan, classical alternative to American Protestant fundamentalism.

Ward’s ceremonial fires at Vestavia, documented in contemporary accounts, were his attempt to maintain the sacred flame of civilization on an Alabama mountaintop. These fires symbolized continuity in the face of change, vigilance against barbarism, and moral light in a darkening world. They were both literal flames during parties and festivals and metaphorical flames in the form of year-round garden lighting that created a “constellation” visible from the valley. His green, red, and white beacon system was another form of the eternal flame, constantly signaling the estate’s status and Ward’s presence.

0 Comments