The Architecture of Exclusion: Understanding America’s Most Deliberate Suburb

In the rolling hills just southeast of Birmingham, Alabama, lies a municipality that represents perhaps the most successful experiment in socio-spatial engineering in American suburban history. Mountain Brook isn’t merely wealthy—with a median household income of $191,128, it has achieved a level of affluence that places it among the nation’s most exclusive communities. But this extraordinary concentration of wealth isn’t an accident of geography or market forces. It’s the deliberate outcome of nearly a century of calculated planning decisions, policy maneuvers, and psychological manipulation that transformed a visionary’s dream of a garden suburb into a fortress of privilege.

To understand Mountain Brook is to witness how aesthetic choices become economic barriers, how zoning laws encode social hierarchies, and how educational excellence can become a source of psychological torment. This is the story of a community that perfected the American suburban ideal—and in doing so, revealed its fundamental contradictions.

Part I: The Vision of Robert Jemison Jr. – Engineering Paradise

The Master Builder’s Psychology

Robert Jemison Jr., born in 1878, wasn’t just a developer—he was Birmingham’s financial architect. Through his corporation established in 1888, which included real estate, investment banking, and mortgage companies, Jemison functioned as what the Birmingham Public Library archives describe as the “central nervous system for Birmingham’s financial and physical growth.” His early developments—Ensley Highlands, Earle Place, Central Park—followed traditional urban grid patterns. But when he turned his attention to the land that would become Mountain Brook, something fundamental shifted in his vision.

The shift wasn’t merely aesthetic; it was psychological. Jemison, the great-nephew of a Confederate senator, carried within him the Southern aristocratic ideal of the landed estate, the pastoral retreat from urban complexity. His vision for Mountain Brook represented a profound rejection of the industrial city he had helped build—a desire to create what he explicitly termed a “peaceful retreat” for those who had profited from Birmingham’s furnaces and foundries.

This psychological foundation—the desire for separation, for elevation both literal and metaphorical—would become the community’s defining characteristic. Jemison wasn’t just developing land; he was engineering a social hierarchy made manifest in space.

Warren Manning’s Landscape of Exclusion

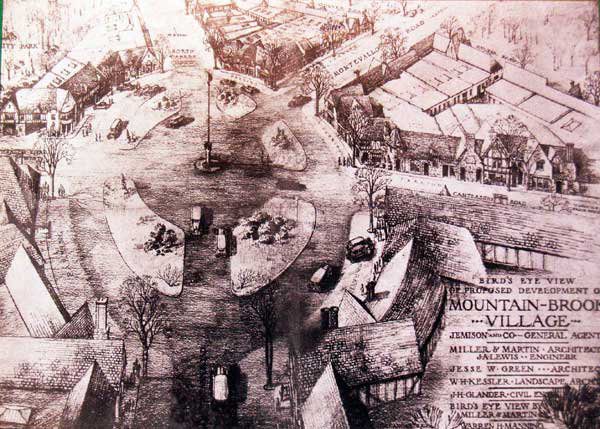

To realize his vision, Jemison enlisted Warren H. Manning, the renowned Boston landscape architect whose 1929 plan would define Mountain Brook’s physical and psychological character for the next century. Manning’s design philosophy, which he called “reverence for place,” sounds benign, even enlightened. But examined closely, it reveals itself as a sophisticated mechanism of exclusion.

Manning rejected the democratic grid in favor of winding roads that followed natural contours. He preserved Shades Creek’s floodplains for scenic value. He mandated estate-sized lots that showcased ancient trees and rock formations. The early planning documents reveal his intention to create a community that would “showcase the distinctive natural features of the ridge and valley lands.”

But this naturalistic approach had profound economic implications. As urban planning research demonstrates, low-density development following topographical features inherently increases infrastructure costs—roads must be longer, utilities more extensive, services more dispersed. Only those with substantial wealth could afford to live in such an intentionally inefficient landscape. The aesthetic choice was, from the beginning, an economic filter.

The three commercial villages—Mountain Brook Village, Crestline Village, and English Village—were designed with Tudor Revival architecture, importing an “Old World charm” that had nothing to do with Alabama’s actual history. This aesthetic colonization served a crucial psychological function: it allowed residents to imagine themselves as inheritors of English aristocratic traditions rather than beneficiaries of Birmingham’s industrial boom.

Part II: The Legal Architecture of Apartheid

Incorporation as Insulation

Mountain Brook’s incorporation on May 24, 1942, represented more than administrative convenience—it was an act of preemptive defense against demographic change. The new city immediately adopted Alabama’s first Council-Manager form of government, prioritizing professional administration over democratic participation. The current governance structure maintains this approach, with an appointed city manager handling day-to-day operations while the elected council sets policy.

But the most significant early policy decisions weren’t about street maintenance or garbage collection. They were about population control. The original development covenants, as documented in historical research, included explicit racial restrictions. Mountain Brook was founded as a “whites-only town,” with property deeds containing legally enforceable racial covenants that prevented sale or occupancy by Black families.

These weren’t subtle dog whistles—they were explicit statements of racial exclusion that reflected the national real estate codes of the era, which sought to protect white neighborhoods from what the industry termed “infiltration” by “inharmonious racial groups.”

The Zoning Weapon

While racial covenants would eventually be struck down by courts, Mountain Brook had already developed a more sophisticated and legally durable mechanism of exclusion: zoning. The city’s zoning ordinance, which mandates minimum lot sizes of 30,000 square feet (approximately 0.69 acres), represents one of the most restrictive in the nation.

This requirement isn’t merely about preserving green space or maintaining aesthetic standards. Research on exclusionary zoning demonstrates that minimum lot sizes function as wealth tests, ensuring that only those who can afford nearly an acre of some of Alabama’s most expensive land can live in Mountain Brook. The current property assessment base exceeds $896 million, generating the tax revenue necessary to maintain superior services while keeping tax rates relatively moderate.

The genius—if we can call it that—of Mountain Brook’s zoning strategy is how it converts aesthetic preferences into economic barriers that achieve racial exclusion without mentioning race. The prohibition on apartments, townhouses, or any form of multi-family housing ensures that no affordable options exist within city limits. Every residence must be a single-family estate, every lot must be substantial, every structure must conform to stringent architectural standards.

Part III: The School Secession – Education as Fortification

Brown v. Board and the Great Escape

The creation of Mountain Brook City Schools in the 1950s represents the most consequential decision in the city’s history—a deliberate act of educational secession designed to avoid racial integration. Following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, Alabama passed legislation enabling municipalities to form independent school districts. Mountain Brook seized this opportunity, creating what Birmingham Watch identifies as an explicitly segregationist institution.

This wasn’t a subtle maneuver. Research on Birmingham’s school segregation demonstrates that the formation of “Over the Mountain” school districts, including Mountain Brook, was fundamentally about maintaining racial homogeneity. The timing—immediately following Brown—and the demographics—overwhelmingly white then and now—make the intent unmistakable.

The Excellence Trap

Yet something unexpected happened. The segregated school system, funded by extraordinary property wealth and supplemented by private donations through the Mountain Brook Schools Foundation, achieved genuine academic excellence. Every school in the district has received Blue Ribbon recognition. Mountain Brook High School consistently ranks in the nation’s top 1% of non-magnet schools. The average ACT score of 26.7 far exceeds state and national averages.

This excellence created a powerful feedback loop. Superior schools justified high property values, which generated tax revenue for better schools, which attracted affluent families, which drove property values higher. The school system became not just an educational institution but the economic engine of the entire community—what some researchers call the “education-property value nexus.”

But this success came with a hidden cost that wouldn’t be fully recognized for decades.

Part IV: The Psychology of Exclusivity

Mimetic Dominance and the Luxury of Place

Mountain Brook’s appeal can’t be explained solely through quality-of-life metrics. Research from the Chicago Booth School of Business on the psychology of exclusivity reveals a fundamental human motivation: we value things more highly when others desire them but can’t have them. This phenomenon, termed “mimetic dominance-seeking,” means people will pay premiums of 50% or more for exclusive status.

Mountain Brook residency functions as what researchers identify as “cultural capital”—a marker of sophisticated taste and social distinction. The community’s barriers to entry aren’t bugs in the system; they’re features. The difficulty of obtaining Mountain Brook residency is precisely what makes it valuable to those who achieve it.

This psychology helps explain why Mountain Brook remains, as ComebackTown notes, such a “lightning rod” in regional discussions. The community’s exclusivity generates both intense desire and deep resentment—a dynamic that reinforces the very boundaries it claims to transcend.

The Performance of Perfection

Life in Mountain Brook requires constant performance of success. The manicured gardens that define the community’s aesthetic aren’t just landscaping—they’re statements of cultural belonging. The Tudor Revival architecture isn’t just style—it’s costume, allowing residents to perform a version of aristocratic refinement.

This performance extends to every aspect of life. The community feedback platform MB Listens reveals residents’ preoccupations: maintaining “character,” preserving “standards,” protecting “quality of life.” These euphemisms encode deeper anxieties about status, exclusion, and the constant threat that paradise might be lost if vigilance weakens.

Part V: The Achievement Crisis – When Success Becomes Pathology

The At-Risk Aristocracy

In 2019, the National Academies of Sciences made a startling declaration: youth in high-achieving schools should be classified as an “at-risk” population, comparable to children living in poverty or foster care. This designation wasn’t about material deprivation but about the psychological costs of extreme achievement pressure.

For Mountain Brook’s youth, the pressure begins early and never relents. The expectation isn’t just success but exceptional success—admission to elite universities, prestigious careers, the ability to maintain their parents’ socioeconomic status. The district’s own data shows 95% of graduates attending four-year universities, but this statistic masks the psychological toll of maintaining such standards.

Research on high achievers reveals a constellation of mental health challenges that Alabama therapists report seeing regularly: chronic anxiety, clinical depression, impostor syndrome, and burnout. The pressure isn’t just academic—it’s existential. Students understand, often explicitly, that their performance directly impacts property values, that their test scores are part of the community’s economic infrastructure.

The Infrastructure of Intervention

The scope of Mountain Brook’s youth mental health crisis can be measured by the community’s response. The school system’s resource list includes extensive mental health services. All In Mountain Brook, a community organization, focuses specifically on suicide prevention and mental wellness. The city has established connections with the Psychiatric Intake Response Center at Children’s of Alabama.

These aren’t precautionary measures—they’re crisis responses to documented problems. The community that achieved everything it set out to achieve finds itself investing heavily in mitigating the psychological damage of that achievement. The paradise that Robert Jemison envisioned has become, for many young residents, a pressure cooker where the fear of failure overshadows any joy in success.

The Property Value Trap

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of Mountain Brook’s achievement culture is how it explicitly links student performance to real estate values. School administrators acknowledge feeling pressure to maintain high test scores to “prop up real estate values in the area.” This creates a perverse dynamic where children’s mental health is sacrificed to maintain their parents’ property investments.

This isn’t metaphorical—it’s a material reality. Every decline in test scores threatens property values. Every student who struggles represents a potential economic liability. The children of Mountain Brook carry not just their own futures but the community’s entire economic model on their shoulders.

Part VI: The Environmental Paradox – When Beauty Becomes Pollution

The Burden of the Aesthetic Ideal

Mountain Brook’s commitment to aesthetic perfection extends to its landscapes, where estate-sized lots feature immaculate lawns that embody the community’s values of order and refinement. But this aesthetic ideal carries an environmental cost that directly contradicts the community’s founding principle of natural preservation.

The Shades Creek Watershed Management Plan documents the consequences: excessive nutrient loading from fertilizer runoff, chronic erosion, degraded water quality. The very creek that Warren Manning sought to preserve as a scenic amenity has become a victim of the aesthetic standards his plan established. The manicured perfection of Mountain Brook’s lawns is literally poisoning the waterway that defines its geography.

This environmental degradation reveals a fundamental contradiction in Mountain Brook’s identity. The community that prides itself on preserving natural beauty is simultaneously destroying it through the pursuit of artificial perfection. The gardens that signify belonging are ecological disasters. The lawns that demonstrate wealth are sources of pollution.

Regional Cooperation Through Crisis

Ironically, environmental crisis may be forcing Mountain Brook into the regional cooperation it has historically resisted. The Shades Creek Greenway project, which requires coordination with Birmingham and other municipalities, represents a rare instance of Mountain Brook acknowledging its interdependence with surrounding communities.

The creek doesn’t respect municipal boundaries. Pollution from Mountain Brook’s lawns affects downstream communities. The need for watershed management creates what policy researchers call “forced collaboration”—cooperation driven not by goodwill but by ecological necessity.

Part VII: The Colonial Economy and Regional Dynamics

The Parasitic Paradise

Mountain Brook’s relationship with Birmingham exemplifies what critics describe as a “colonial economy”—extracting value from the urban core while contributing little to its maintenance. Residents depend on Birmingham for employment, cultural amenities, and infrastructure, yet the municipality’s policies ensure that its tax revenues remain within its borders.

This dynamic isn’t unique to Mountain Brook, but the community’s extreme wealth makes it particularly stark. The per capita income differential between Mountain Brook and Birmingham represents one of the nation’s most extreme examples of metropolitan inequality. The prosperity that Mountain Brook enjoys depends directly on the urban economy it refuses to support through regional tax sharing or consolidated governance.

The Reddit Question

The persistence of Mountain Brook’s mystique can be seen in online discussions where newcomers struggle to understand the community’s appeal. A Reddit thread asking “Can someone help me understand why Mountain Brook is considered upscale?” reveals the gap between reputation and visible reality. Respondents cite the schools, the exclusivity, the history—but struggle to articulate what makes the community worth its premium prices beyond these circular justifications.

This confusion points to a deeper truth: Mountain Brook’s value is largely psychological. It’s not just about the schools or the houses or the trees—it’s about what living there signifies, about the identity it confers, about the boundaries it maintains.

Part VIII: The Architecture of Isolation

The Governance of Exclusion

Mountain Brook’s Council-Manager government operates with remarkable efficiency, managing a budget that would be the envy of many larger cities. The five-member council, elected at-large rather than by district, ensures that community-wide interests (maintaining property values) always supersede any particular neighborhood’s concerns.

The appointment of school board members by the City Council creates an unusual integration of municipal and educational governance. This structure ensures that school policy never diverges from the community’s economic interests. There’s no possibility of a rogue school board implementing policies that might threaten property values or demographic homogeneity.

The Comprehensive Plan’s Contradictions

Mountain Brook’s planning documents reveal the tensions within its identity. The comprehensive plan speaks of “diversity” and “sustainability” while maintaining zoning codes that make both impossible. The community profile celebrates “small-town charm” while exhibiting metropolitan wealth concentration.

These contradictions aren’t oversights—they’re strategies. By speaking the language of inclusion while maintaining structures of exclusion, Mountain Brook can present itself as progressive while preserving its fundamental character. The planning documents perform openness while the zoning code enforces closure.

Part IX: The Future of the Fortress

Demographic Destiny

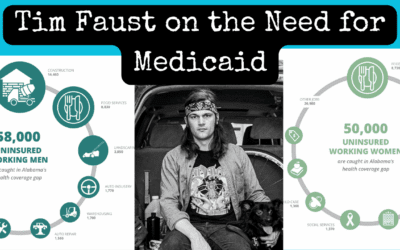

Mountain Brook faces a demographic challenge that threatens its carefully constructed equilibrium. The population of 22,160 has remained relatively stable, but the age distribution is shifting. Young families struggle to afford entry, even with high incomes. Elderly residents have few options for downsizing within the community due to the absence of smaller homes or condominiums.

This demographic trap is a direct result of the zoning policies that protected Mountain Brook’s exclusivity. The mandate for estate-sized lots means there’s no housing diversity, no lifecycle housing options. Residents must either maintain large properties into old age or leave the community entirely. The fortress that keeps others out also keeps residents in, unable to adapt to changing life circumstances.

The Mental Health Reckoning

The recognition of Mountain Brook’s youth as an at-risk population represents a potential inflection point. The community that prided itself on producing exceptional children must now reckon with the psychological damage that exceptionalism inflicts. The investment in mental health resources through All In Mountain Brook and school-based services suggests at least some recognition of the crisis.

But addressing symptoms without changing structures has limited efficacy. As long as children’s academic performance remains tied to property values, as long as the community’s identity depends on exclusivity and achievement, the pressure will persist. The question is whether Mountain Brook can imagine a version of itself that maintains excellence without pathology, distinction without destruction.

The Sustainability Question

The environmental challenges facing Shades Creek represent another forcing function for change. The community’s aesthetic standards are literally unsustainable, poisoning the watershed that defines its geography. The need for regional cooperation on environmental issues may crack open the fortress mentality, creating precedents for other forms of collaboration.

But environmental cooperation is easier than social integration. Mountain Brook can work with Birmingham on greenways while maintaining its exclusionary zoning. It can address water quality while preserving demographic homogeneity. The environmental crisis may force some changes, but whether these lead to fundamental transformation remains doubtful.

Part X: Lessons from the Laboratory

The Success of Spatial Engineering

Mountain Brook proves that deliberate spatial engineering can create and maintain extraordinary concentrations of wealth and achievement. Through careful planning, strategic policy, and sustained political will, a community can effectively separate itself from regional challenges while capturing regional resources. The median household income of $191,128 and property assessments approaching $900 million demonstrate the material success of this approach.

For those interested in replicating Mountain Brook’s model, the formula is clear: establish aesthetic standards that require wealth to maintain, implement zoning that prevents affordable housing, secure educational independence to guarantee quality and exclusivity, and maintain political structures that prioritize property values over all other concerns.

The Costs of Perfection

But Mountain Brook also demonstrates the hidden costs of engineered exclusivity. The mental health crisis among its youth reveals that even privilege can become pathology when taken to extremes. The environmental degradation shows that aesthetic perfection can be ecologically destructive. The regional tensions illustrate how local success can undermine metropolitan cohesion.

These aren’t unfortunate side effects—they’re structural consequences of Mountain Brook’s model. A community built on exclusion will always generate pressure on those inside and resentment from those outside. A place that defines itself through achievement will always create anxiety about failure. A landscape maintained to artificial standards will always conflict with natural systems.

The American Dilemma Crystallized

Mountain Brook represents the American suburban dilemma in its purest form: the tension between individual success and collective wellbeing, between local control and regional equity, between the desire for community and the imperative of exclusion. It shows what’s possible when a group of people with sufficient resources decide to create their own reality—and what’s lost in that creation.

The community that Robert Jemison envisioned as a peaceful retreat has become a fortress of anxiety. The garden suburb that Warren Manning designed to harmonize with nature has become an ecological burden. The schools that were created to avoid integration have become pressure cookers that damage the very children they’re meant to serve.

The Perfect Prison

Mountain Brook, Alabama stands as perhaps the most successful example of suburban social engineering in American history. Through nearly a century of calculated planning decisions, policy maneuvers, and psychological manipulation, it has created an enclave of extraordinary wealth, educational achievement, and aesthetic refinement. By every material measure, it has achieved its founders’ goals and more.

Yet this success has come at costs that are only now being fully recognized. The youth mental health crisis, the environmental degradation, the regional inequality—these aren’t failures of the Mountain Brook model but its logical outcomes. The community has created what we might call a “perfect prison”—a place of extraordinary privilege that also constrains and damages those within it.

The story of Mountain Brook asks us to consider what we’re optimizing for when we build communities. If the goal is property values and test scores, Mountain Brook provides a blueprint. If the goal is human flourishing and ecological sustainability, it offers a cautionary tale. The community that achieved everything it set out to achieve now faces the question of whether those achievements were worth their price.

As Mountain Brook enters its ninth decade, it stands at a crossroads. It can continue to perfect its model of exclusion, accepting the psychological and environmental costs as necessary prices for privilege. Or it can begin to imagine a different future—one that maintains excellence without pathology, distinction without destruction, community without exclusion.

The choice it makes will reveal not just Mountain Brook’s future but something essential about the American experiment itself: whether we can create places of genuine prosperity that don’t depend on others’ deprivation, whether we can build communities that elevate without isolating, whether we can achieve success that doesn’t consume those who attain it.

The gardens of Mountain Brook remain magnificent, the schools exceptional, the property values astronomical. But behind the Tudor facades and manicured lawns, a question haunts this perfect suburb: What does it profit a community to gain the whole world if it loses its soul? Mountain Brook has spent nearly a century avoiding this question. The mental health statistics, the environmental data, and the regional tensions suggest it can’t avoid it much longer.

The fortress on the hill has never been more valuable or more vulnerable. Its walls have never been higher or more fragile. Mountain Brook has achieved the American Dream and discovered it might be a nightmare. What it does with that discovery will determine not just its own future but the future of the suburban ideal it has so perfectly, and so problematically, embodied.

0 Comments