What was the Aum Shinrikyo Cult?

Cultural Anxieties, Psychological Manipulation, and a Cult’s Deadly Legacy

Stealing from Other Systems Aum Shinrikyo, like many cults, appropriated and repackaged beliefs and practices from various religions, philosophies, and scientific fields, rather than developing a wholly original worldview. The group cobbled together elements of Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity and New Age spirituality into an eclectic amalgam used to justify their leader’s authority.

Aum’s central practice of spiritual training through ascetic yoga and meditation was borrowed from Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Shoko Asahara, the cult’s founder, styled himself as a holy man or guru in the mold of figures like Buddha or Jesus Christ, claiming special enlightenment and spiritual powers.

The group’s belief in an impending apocalypse, after which only Aum members would survive to rebuild the world, echoes fundamentalist Christian ideas about the end times. Asahara also incorporated pseudo-scientific ideas into his teachings, claiming that modern technology and materialism were poisoning the world.

At the core of Aum’s philosophy was the Buddhist concept of Poa, which they reinterpreted to argue that non-believers should be killed to stop them from accumulating negative Karma. In this way, the cult twisted teachings about non-violence for its own violent ends. Ultimately, Aum stitched together preexisting religious, spiritual and scientific threads to create a patchwork ideology that seemed profound and ahead of its time, but lacked true substance or originality.

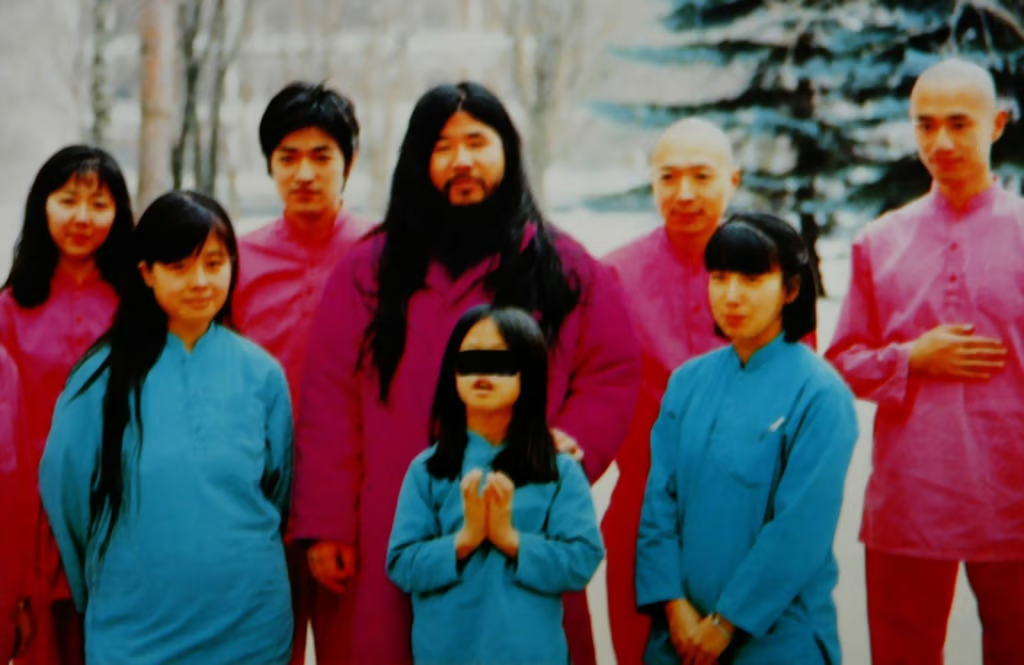

Asahara’s Leadership and Psychology

Shoko Asahara, born Chizuo Matsumoto in 1955, was a partially blind acupuncturist and failed politician before founding Aum Shinrikyo in 1984. Bullied as a child due to his disability, Asahara developed deep insecurities and resentments. He craved power, respect, and a sense of importance.

Despite lacking formal religious training, Asahara was a skilled speaker and manipulator. He had a forceful, charismatic personality and claimed to possess spiritual powers like levitation and mind-reading. Members were encouraged to see him as a living Buddha.

Like other cult leaders, Asahara demanded absolute loyalty and obedience from his followers. He used techniques like sleep deprivation, starvation diets, and constant indoctrination to break down followers’ independent will. Unique to Aum was the use of technological devices like electrodes to monitor followers’ brainwaves during meditation.

However, Asahara’s need for control stemmed from deep-seated insecurities. His visions of grandeur concealed a fragile ego. Ultimately, when legal pressure on the cult mounted in the 1990s, Asahara lashed out in violence, seemingly to protect his power and self-image as much as his spiritual movement.

Rise and Fall Timeline

1984: Shoko Asahara founds Aum Shinrikyo as a yoga and meditation group.

1987: Asahara and 24 followers run for election to Japanese parliament, but all suffer defeat. Asahara begins preaching about an apocalyptic World War III.

1988: Aum Shinrikyo is granted official religious corporation status by the Japanese government, making it tax-exempt. Membership surpasses 4,000.

1989: Aum members start mysteriously disappearing. It’s later revealed they were killed for attempting to leave the group.

1990: Aum begins stockpiling chemical weapons and holding paramilitary training exercises. Membership surpasses 10,000.

1992: Asahara publishes Declaring Myself the Christ, claiming to be the “Lamb of God.”

1994: The cult is suspected in the disappearance of lawyer Tsutsumi Sakamoto and his family. He was working on a class action lawsuit against Aum at the time.

1995: On March 20, Aum members release sarin nerve gas on the Tokyo subway, killing 12 and injuring over 5500, in an attempt to bring about Asahara’s prophesied doomsday war.

May 1995: Asahara is arrested. Investigations reveal the cult was responsible for another sarin gas attack the previous year.

1996-2000: Aum leaders are put on trial. Asahara is ultimately sentenced to death, along with 12 other cult members.

2000: Remaining Aum members establish Aleph as a successor group to the cult, but under strict government surveillance.

2018: Asahara and six other cult leaders are executed by hanging for their role in the Tokyo subway attack and other murders.

The Cult and its Cultural Context

Aum Shinrikyo’s rise in 1980s Japan can be partly attributed to the cultural anxieties of the time. Japan’s postwar economic boom was slowing down and its future seemed uncertain. Traditional social structures were breaking down as the country rapidly modernized.

In this climate of change, some young people felt alienated, aimless, and distrustful of mainstream institutions. Aum’s vision of an alternate spiritual community that rejected materialism and promised transcendence beyond the struggles of modern life appealed to those feeling left behind or dissatisfied by Japan’s direction.

Psychologically, Aum provided members a way to compensate for feelings of powerlessness and insecurity by subsuming themselves into a greater whole. By dedicating themselves totally to Asahara and his mission, they found a sense of meaning, purpose and importance they lacked in ordinary life.

Adjacent conspiracy theories and apocalyptic ideas were also common in Japan at the time. Asahara’s prophecies of World War III tapped into broader preoccupations in the culture, giving followers the thrilling sense that they possessed special knowledge of secret truths.

Exit and Deprogramming

After Asahara’s 1995 arrest, Japanese police launched a campaign to dismantle the cult’s remaining infrastructure and deprogram members. Cult compounds were raided, assets were seized, and followers faced pressure to renounce their beliefs and reintegrate into society.

Due to the intense mental conditioning used by the cult, many members initially resisted. Some had spent up to a decade utterly submitting to Asahara’s authority, to the point that they struggled with basic decision-making. Others suffered severe anxiety, depression and PTSD-like symptoms upon the cult’s dissolution.

However, with time and counseling, many were able to rebuild their lives. For some, learning about the full extent of Asahara’s deceptions and crimes was the push they needed to finally leave. Others found that reconnecting with family, working a job, or building new social ties outside the cult setting gradually loosened its psychological grip.

Still, a core of diehard believers persisted. These followers went on to join Aleph and other Aum offshoots in the late 1990s and 2000s. Some maintained that Asahara was innocent and had been framed by a conspiracy between the government and rival religions. Even after Asahara’s execution, Aleph continues to revere him as a spiritual leader.

Recognizing Abuse and Control

Aum Shinrikyo employed coercive control tactics that are found not just in cults, but in abusive personal relationships, extreme political movements, and high-pressure religious and business groups. Recognizing the signs can help prevent exploitation:

- Social isolation and fostering an “us vs. them” mentality

- Absolute authoritarian leadership that cannot be questioned

- Required demonstrations of loyalty, such as monetary “investment”

- Control of members’ daily lives and relationships

- Guilt, shame, or withholding affection used to influence behavior

- Special insider language that reinforces a feeling of superiority

- Extreme promises that seem too good to be true

In personal relationships, red flags include partners who try to restrict outside contact, demand access to money, or constantly criticize to undermine self-esteem. In politics, leaders who demonize opponents, insist on total faith and obedience, or promote apocalyptic thinking may be using cult-like manipulation. In high-pressure business settings, beware of constant upselling using insider lingo and insinuations that “success” depends on buying the next thing.

Ultimately, while human social dynamics make everyone somewhat vulnerable to manipulation, critical thinking is the best defense. Carefully assessing extraordinary claims, being wary of emotional exploitation, and maintaining relationships outside any one group can prevent the sort of all-consuming involvement that enables control.

Bibliography

Lifton, Robert Jay. Destroying the World to Save It: Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism. New York: Holt, 1999.

Mullins, Mark R. “The Legal and Political Fallout of the ‘Aum Affair.'” Japan Christian Review 63 (1997): 55-68.

Metraux, Daniel Alfred. Aum Shinrikyo’s Impact on Japanese Society. Lewiston, N.Y.: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2000.

Oxford Handbook on Religion and Violence. Edited by Michael Jerryson, Mark Juergensmeyer, & Margo Kitts. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Kaplan, David E. and Andrew Marshall. The Cult at the End of the World: The Terrifying Story of the Aum Doomsday Cult, from the Subways of Tokyo to the Nuclear Arsenals of Russia. New York: Crown Publishers, 1996.

Goldwag, Arthur. Cults, Conspiracies, and Secret Societies. New York: Vintage Books, 2009.

Hassan, Steven. Combating Cult Mind Control: The #1 Best-Selling Guide to Protection, Rescue and Recovery from Destructive Cults. Newton, MA: Freedom of Mind Press, 2015.

Other Cults and Conspiracy Theories

0 Comments