What were the Situationists International

The Situationist International (SI) was a radical avant-garde movement that emerged in the 1950s and reached its peak of influence in the late 1960s, around the time of the May 1968 uprising in France. Founded on the idea of fusing art, politics, and everyday life into a revolutionary praxis, the SI sought to overthrow the alienating and oppressive structures of modern capitalist society. At the heart of their critique was the concept of the spectacle, developed by Guy Debord in his 1967 book “The Society of the Spectacle.” For Debord and the Situationists, the spectacle referred to the domination of social life by images, representations, and commodities, leading to a state of passive consumption, alienation, and the degradation of authentic human experience.

In many ways, the SI embodied the archetype of the trickster, a boundary-crossing, convention-defying figure who subverts established norms through wily strategies, playful mischief, and creative manipulation. Like the trickster, the SI aimed to disrupt the existing order through unconventional tactics and provocations, from the practice of détournement (the subversive alteration of cultural elements) to the construction of situations (ephemeral moments of authentic, unalienated experience).

This paper will explore the SI’s embodiment of the trickster archetype and its relevance to fields like anthropology, psychology, and Jungian thought. It will examine how the SI’s emphasis on play, spontaneity, and the power of the unconscious echoed the trickster’s transgressive and transformative qualities. At the same time, it will consider the limitations and contradictions of the SI’s approach, and the ways in which their critique of modern society both reflected and challenged prevailing intellectual currents of their time.

Origins and Development of the SI

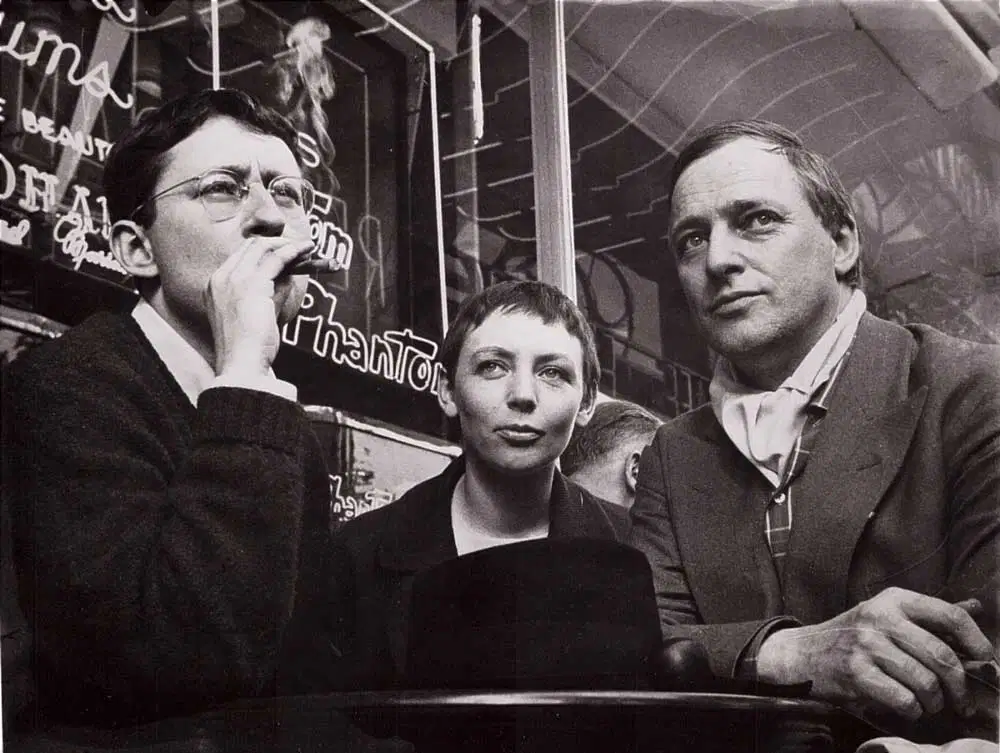

The Situationist International had its roots in the avant-garde artistic and political milieu of postwar Europe. In the early 1950s, Guy Debord and other young radicals formed the Letterist International, a Paris-based group that experimented with poetry, film, and urban drifting. Influenced by Dada, Surrealism, and Marxism, the Letterists sought to break down the boundaries between art and life, and to create new forms of expression and experience beyond the confines of the capitalist spectacle.

In 1957, Debord and his comrades joined forces with artists and activists from other countries to found the Situationist International. The SI quickly developed a reputation for its uncompromising rhetoric and its daring interventions in the fields of art, politics, and everyday life. In their journal “Internationale Situationniste” and in books like Raoul Vaneigem’s “The Revolution of Everyday Life,” the Situationists launched a devastating critique of consumer society, bureaucratic socialism, and the cultural conformism of the postwar era.

At the same time, the SI was rife with internal conflicts and contradictions. The group was notoriously sectarian and hierarchical, with Debord and other leading members frequently purging or excommunicating those who deviated from the official line. This led to a series of splits and schisms, as well as a gradual shift from a focus on art and urbanism to a more explicitly political and revolutionary stance.

Key Ideas and Practices

The Spectacle

The concept of the spectacle was the cornerstone of the SI’s theoretical edifice. For Debord, the spectacle was not simply the mass media or advertising, but a much broader social phenomenon that permeated every aspect of modern life. In his view, the spectacle was a form of alienated representation that had replaced authentic human experience and social relations. Under the reign of the spectacle, individuals were reduced to passive spectators, consuming pre-packaged images and commodities instead of actively shaping their own lives and destinies.

Debord argued that the spectacle was the product of the capitalist mode of production, which had transformed everything – from culture to politics to personal identity – into a commodity to be bought and sold on the market. In this sense, the spectacle was not just a distortion of reality, but a reflection of the fundamental alienation and reification of human life under capitalism.

Détournement and the Construction of Situations

To combat the spectacle, the Situationists developed a range of subversive tactics and practices. One of the most important was détournement, the art of hijacking and repurposing existing cultural elements for radical ends. By altering the context and meaning of familiar images, slogans, and artifacts, the SI sought to jolt people out of their complacency and reveal the absurdity and emptiness of consumer society.

Another key Situationist concept was the construction of situations – ephemeral moments of authentic, unalienated experience created through the free interplay of people and their surroundings. These situations were meant to be transformative, liberatory ruptures in the fabric of everyday life, opening up new possibilities for creativity, desire, and self-realization.

The Situationists believed that the construction of situations was the key to overcoming the spectacle and creating a new, post-capitalist society. Rather than waiting for a distant revolution, they argued, radicals should begin experimenting with new forms of life and social relations in the here and now. This emphasis on the immediate transformation of everyday life, rather than abstract political programs or ideologies, was a hallmark of the SI’s approach.

Unitary Urbanism and Psychogeography

The SI’s critique of the spectacle was closely linked to their analysis of urban space and the built environment. Drawing on the work of Marxist theorists like Henri Lefebvre, the Situationists argued that the modern city was a key site of alienation and domination, designed to facilitate consumption, surveillance, and control.

To counter this, the SI developed the concept of unitary urbanism – a radical approach to city planning that prioritized the needs and desires of inhabitants over the demands of capital and bureaucracy. Unitary urbanism called for the creation of fluid, malleable spaces that could be constantly adapted and transformed by the people who lived in them.

Closely related to unitary urbanism was the practice of psychogeography – the study of the psychological and emotional effects of urban environments. Through techniques like the dérive (a form of aimless drifting through the city), the Situationists sought to map the hidden contours of desire and resistance that lurked beneath the surface of the rational, functional city.

The SI in May 1968 and Beyond

The Situationist International reached the height of its influence during the May 1968 uprising in France. Although the SI was only one of many groups involved in the rebellion, their ideas and slogans played a key role in shaping the discourse and tactics of the movement. Graffiti and posters bearing Situationist aphorisms appeared throughout Paris, while student occupations and worker strikes echoed the SI’s call for a radical transformation of everyday life.

However, the May events also marked the beginning of the end for the SI. In the aftermath of the uprising, the group was torn by internal disputes and recriminations, as well as by the departure of key members like Raoul Vaneigem. In 1972, Guy Debord formally dissolved the SI, declaring that it had fulfilled its historical mission and was no longer necessary.

Despite its relatively short lifespan, the SI had a profound impact on the counterculture and radical politics of the late 20th century. Their critique of consumerism, media manipulation, and the alienation of everyday life influenced everything from punk rock to the anti-globalization movement. At the same time, their emphasis on play, creativity, and spontaneity inspired a new generation of artists, activists, and dreamers around the world.

The Trickster Archetype Embodied

One way to understand the Situationist International is through the lens of the trickster archetype. Found in myths and folklore around the world, the trickster is a boundary-crossing, convention-defying figure who subverts established norms and structures through wily strategies, playful mischief, and creative manipulation.

Like the trickster, the SI sought to disrupt the existing order of things through a variety of unconventional tactics and provocations. Their practice of détournement – hijacking and repurposing the language and imagery of the spectacle – bears a strong resemblance to the trickster’s penchant for mischievous inversion and sabotage. By turning the tools of domination against themselves, the SI aimed to expose the absurdity and emptiness of consumer society.

The SI’s emphasis on the power of play, spontaneity, and the imagination also echoes the trickster’s ludic and subversive qualities. For the Situationists, the creation of situations was a way of reenchanting the world, infusing everyday life with a sense of magic, wonder, and possibility. This utopian vision of a society in which work and play, art and life are reconciled bears a strong resemblance to the trickster’s disruptive and liberatory role in traditional cultures.

Moreover, the SI’s organizational style and group dynamics had a distinctly tricksterish quality. The Situationists were notorious for their internal conflicts, schisms, and purges, with members constantly challenging each other’s positions and practices. This culture of irreverent debate and self-critique reflected both the SI’s commitment to radical democracy and the trickster’s love of paradox, contradiction, and the carnivalesque overturning of roles and identities.

From a Jungian perspective, the SI’s embrace of the trickster archetype can be seen as an attempt to integrate the repressed, shadow aspects of the psyche and society. For Jung, the trickster represented the primitive, irrational, and subversive forces that civilized cultures sought to suppress or control. By unleashing these transgressive energies, the SI hoped to shatter the illusions of the spectacle and catalyze a radical transformation of consciousness and social relations.

This Jungian dimension is also evident in the SI’s fascination with myth, symbolism, and the power of the unconscious. Debord’s films, for instance, are full of dreamlike, surreal imagery that seems to tap into the collective archetypes and fantasies of modern society. The notion of the “revolutionary imaginary” as a wellspring of utopian desires and aspirations likewise resonates with Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious as a reservoir of primordial, transformative energy.

At the same time, the SI’s approach differed from classical Jungianism in its emphasis on the necessity of external, material transformation. While Jung tended to focus on the inner journey of individuation, the Situationists insisted that personal liberation was inseparable from the radical restructuring of social relations. Their goal was not merely to explore the depths of the psyche, but to actively create a world in which the free development of each individual was the condition for the free development of all.

Anthropological and Sociological Resonances

The Situationist International’s ideas also have striking parallels with certain currents in anthropology and sociology. Their fascination with the gift economy and the transformative power of festival and ritual echoes the work of thinkers like Marcel Mauss and Georges Bataille, who saw in the practices of premodern cultures a radical alternative to the utilitarian logic of capitalism.

Like these anthropologists, the Situationists were interested in the way that collective acts of creative destruction and transgression could dissolve social hierarchies and create new forms of solidarity and meaning. The potlatch ceremonies of the Pacific Northwest, the sacrificial rituals of ancient religions, the carnivals of medieval Europe – all of these served as inspiration for the SI’s vision of a world turned upside down, a world in which the sacred and the profane, the high and the low, would be joyfully reconciled.

At the same time, the SI’s uncompromising anti-colonial politics and their critique of Western ethnocentrism set them apart from the primitivist romanticism of some earlier avant-garde movements. For the Situationists, the point was not to idealize or imitate premodern cultures, but to extract from them the timeless principles of revolt and self-determination that could be applied to the struggles of the present.

In this sense, the SI’s project was in line with the radical anthropology of the 1960s and 70s, which sought to challenge the complicity of the discipline with colonial domination and capitalist exploitation. Like the SI, thinkers such as Dell Hymes and Stanley Diamond called for a “reinvention of anthropology” that would place the needs and desires of oppressed peoples at the center of the research agenda.

The SI’s ideas also resonated with the emerging field of critical sociology, represented by figures like Henri Lefebvre and Jean Baudrillard. Like the Situationists, these thinkers sought to expose the hidden power structures and ideological mystifications that shaped the fabric of everyday life under capitalism. Lefebvre’s critique of the “bureaucratic society of controlled consumption” and Baudrillard’s theory of the “simulacrum” owed much to the SI’s pioneering analysis of the spectacle.

However, while the SI shared many affinities with these intellectual currents, they also fiercely guarded their independence and originality. The Situationists had little patience for academic jargon or theoretical hairsplitting, and they frequently denounced the “recuperation” of their ideas by the very institutions they sought to overthrow. For them, radical theory was inseparable from radical practice, and the ultimate test of any concept was its ability to transform the concrete conditions of everyday life.

Limitations and Contradictions

Despite their many insights and innovations, the Situationist International was not without its limitations and contradictions. One of the most obvious was the group’s notorious sectarianism and infighting, which often seemed to prioritize ideological purity over practical efficacy. The SI’s insistence on total opposition to the spectacle sometimes led them to reject potential allies and coalitions, and their frequent purges and excommunications created an atmosphere of paranoia and self-righteousness.

There were also tensions and ambiguities in the SI’s theoretical framework. While their critique of the spectacle was powerful and prescient, it sometimes tended towards a reductive economism that downplayed the complexity and specificity of cultural and political struggles. The SI’s emphasis on the liberatory potential of technology and automation, meanwhile, sat uneasily with their primitivist romanticism and their skepticism towards the supposed benefits of “progress.”

Moreover, for all their talk of “realizing art” and “abolishing work,” the Situationists never quite managed to articulate a convincing vision of what a post-revolutionary society might actually look like. Their calls for the immediate establishment of workers’ councils and the abolition of the state often seemed more like poetic slogans than practical proposals, and their dismissal of reformist demands and transitional programs as “spectacular” concessions sometimes verged on an apocalyptic purism.

Finally, the SI’s embrace of the trickster archetype and the transgressive power of the unconscious was not without its risks and limitations. While the group’s provocations and interventions could be startlingly effective at puncturing the complacency of the spectacle, they also ran the risk of devolving into empty gestures or self-indulgent provocations. The SI’s celebration of play and spontaneity, meanwhile, sometimes downplayed the hard work and discipline that real social transformation requires.

Glossary of Situationalists International Concepts:

Détournement

- The subversive misappropriation, hijacking, or recontextualization of existing media, images, text and ideas in order to undermine their original meaning or purpose and create new subversive, satirical or revolutionary meanings.

- A key Situationist tactic to challenge the dominant language, images and ideas of consumer capitalism and the “society of the spectacle.”

- Examples include satirically altered advertisements, collages juxtaposing contradictory text and images, or the ironic reuse of well-known quotes.

Dérive

- An unplanned, intuitive way of spontaneously drifting or wandering through an urban environment, guided by the aesthetic contours and ambiances of the surroundings, in order to study the psychogeography of a city.

- A method for creatively exploring urban spaces outside of the usual motives for travel like work or commerce. By dérive one could investigate how different environments evoke distinct emotions and behaviors.

- The aim was to break from habitual, alienated relations to the city to make way for more liberatory and playful forms of urban life.

Unitary Urbanism

- A revolutionary approach to architecture and city planning aiming to break down the segregation of the city into distinct zones of living, working, and consumption and instead create dynamic spaces fostering play, creativity, and community.

- Against the functionalist urbanism of modernist planners, unitary urbanism called for cities organized around the fulfillment of authentic human desires and the “construction of situations.”

- City spaces would be designed to enable and encourage the free creation of the situations, fluid mobility and play. The Situationists experimented with utopian urban plans to this effect.

Constructed Situation

- Deliberately orchestrated events or environments staged by the Situationists aimed at provoking critical awareness of the alienation and passivity of everyday life under capitalism and sparking desire for revolutionary social change.

- Anticipated a future society based around the continuous free construction of situations fulfilling authentic human desires and enabling creativity, play, and a more passionate collective life.

- Examples of constructed situations included Situationist interventions, gatherings and exhibitions designed to jolt audiences out of complacency and into an awareness of their own radical possibilities.

Psychogeography

- The study of the specific psychological and emotional effects of different geographic environments on individuals.

- A Situationist method of investigating how urban spaces are structured to reinforce alienation, consumption, and docility, and experimenting with alternatives.

- Through the dérive and other psychogeographic practices, the Situationists aimed to discover liberating ways of inhabiting and altering the city in opposition to capitalist urbanism.

Spectacle

- In Debord’s analysis, the dominant mode of capitalist society where authentic life is replaced by the passive consumption of images.

- Social life becomes a giant “spectacle” – a never-ending stream of commodified, constructed representations (advertisements, media, brands, etc.) that monopolize appearance and define reality.

- “The spectacle is not a collection of images,” Debord wrote, “rather, it is a social relation among people, mediated by images.” Spectacle obscures and justifies capitalist domination.

Alienation

- For the Situationists, the condition of human life and labor under capitalism in which we are cut off from our authentic creativity, desires, and power and instead live as atomized consumers and workers.

- Everyday life becomes an alienated existence of passively accepting the roles, habits and desires dictated by capitalist culture and the spectacle.

- The Situationists sought the revolutionary overcoming of alienation through the collective “realization of art” in everyday life – the fulfillment of authentic human desire and creativity.

Radical Subjectivity

- The Situationist emphasis on subjective lived experience, authentic desire, spontaneity and creativity as the basis for revolutionary theory and practice.

- Against the abstract and bureaucratic politics of Stalinist “objective” Marxism, the Situationists affirmed the radical possibilities of each individual’s passionate subjective refusal of alienated life.

- The Situationists saw the liberation of human subjectivity via the revolution of everyday life as key to making a true social revolution against capitalism and its spectacle.

Recuperation

- The processes by which originally subversive ideas, practices, and cultural forms are “recovered” by being repackaged and absorbed back into dominant capitalist society, neutering their revolutionary meaning.

- The Situationists saw recuperation as an omnipresent threat against any movement or avant-garde opposing the spectacle. Subversions are turned into harmless spectacles and commodities.

- Debord theorized how capitalism constantly adapts to neutralize threats via this process. The SI tried to resist recuperation through ceaseless innovation of new scandals, ruptures, and negations.

Anti-Cinema

- The Situationist critique and practice of filmmaking in opposition to the dominant commercial/narrative conventions of mainstream cinema and towards revolutionary purposes.

- If the spectacle reduces its viewers to passive consumers, anti-cinema would aim to activate the radical consciousness and creativity of the audience.

- Key anti-cinema works included Debord’s experimental found-footage films like Society of the Spectacle designed to critically awaken the viewer rather than spectacularly pacify them.

Realization and Abolition of Art

- The Situationists were influenced by Dada and Surrealism’s drive to merge art and life, but ultimately deemed these movements failed in abolishing the separation between aesthetic activity and politics/everyday existence.

- For the SI, the revolutionary “realization of art” would mean not elevating art into a specialized profession but diffusing creative activity throughout all spheres of life – the construction of situations.

- They envisioned the “real movement that abolishes the present state of things” would make every individual an artist capable of creatively constructing their own passionate everyday life.

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

0 Comments