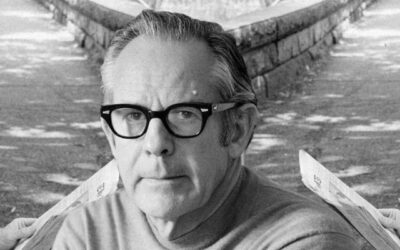

1. Who Was Otto Rank?

Otto Rank (1884-1939) was an Austrian psychoanalyst, writer, and teacher who was one of Sigmund Freud’s closest colleagues and most brilliant students. Rank made significant contributions to psychoanalytic theory before breaking with Freud and developing his own school of thought that emphasized the creative power of the will and the existential anxiety of life and death.

Some of Rank’s key ideas included:

- The Trauma of Birth: Rank saw birth as the original source of anxiety, when we leave the comfort of the womb and face the challenges of the world as separate beings. He believed this early experience shaped our psychological development.

- Will & Creation: Rank focused on the importance of human will, creativity, and our drive to individuate and develop our own identities separate from our parents and society’s expectations. He saw the courage to affirm one’s will as vital for growth.

- Art & Artist: For Rank, the artist was the exemplar of an individual who asserts their creative will to fashion something meaningful and personal in the face of life’s limits and anxieties. He analyzed the psychology of art and the artistic personality.

- Life Fear & Death Fear: Rank described the fundamental human struggle between our fear of life (feeling overwhelmed by the challenges of existence) and our fear of death (being terrified of nonexistence). Facing these fears was crucial for living authentically.

- Therapy as Education: Breaking from Freud’s focus on the past, Rank re-envisioned therapy as a creative, future-oriented process of separation and education for a new way of living according to one’s own will and values.

2. Birth as the Original Trauma

One of Rank’s most radical ideas was his emphasis on the existential significance of birth. In his 1924 book The Trauma of Birth, Rank proposed that the physical event of birth was the source of what Freud called “primal anxiety” – the original experience of overwhelming fear and helplessness that shapes our psychology.

For Rank, birth represents our first great separation – the loss of the nurturing, symbiotic unity of the womb as we are thrust into a world of frustrations and challenges. He suggested this early ordeal sets up the fundamental dialectic of human existence between union and separation, dependence and autonomy.

According to Rank, the rest of life involves symbolically repeating and working through this primal separation from the mother. Our relationships, creative activities, and neurotic patterns all bear the imprint of this original trauma and our efforts to cope with it.

In contrast to Freud’s emphasis on the Oedipus complex and psychosexual development, Rank gave primacy to pre-Oedipal issues of separation, individuation, and the formation of identity. He saw the ego’s struggle to establish itself as an autonomous entity in the face of engulfment anxiety as the key developmental challenge.

While many of Rank’s colleagues rejected his birth trauma theory as too speculative, it anticipated later research on attachment, object relations, and the lifelong impact of early bonding and separation experiences. Rank’s ideas also resonated with the existential focus on facing the realities of aloneness and mortality.

3. The Creative Power of the Will

At the heart of Rank’s psychology was a new emphasis on the importance of human will and creativity. In contrast to Freud’s focus on unconscious drives and the deterministic effects of the past, Rank highlighted our capacity to shape our own lives through acts of intention and imagination.

In his books Art and Artist and Will Therapy, Rank celebrated the power of the creative will to fashion new realities and transcend the limits of biology and circumstance. He saw this capacity as the essence of our humanity – the spiritual spark that allows us to rise above mere instinct and conditioning.

For Rank, the urge to create was a fundamental expression of the life force itself – the élan vital that propels us to individuate, evolve, and give birth to the new. He believed every human being was a potential artist, capable of crafting a unique identity and vision for their existence.

This creative impulse, however, was always in tension with the anxiety of life and death. To affirm one’s will was to face the existential responsibilities and uncertainties of being a self-determining individual. It meant having the courage to separate from the herd, to risk failure and loss, to confront aloneness and mortality.

In his therapeutic work, Rank aimed to support patients in awakening to their creative will and finding the strength to live according to their own values and purpose. He saw therapy not as a cure for illness but as a process of existential education – a way of developing the psychological capacities needed to embrace life in all its possibility and pain.

Rank’s celebration of the creative will was a key influence on humanistic and existential approaches to psychology. His ideas anticipated later research on motivation, agency, and the importance of personal meaning-making. They continue to inspire therapists and individuals seeking to live more authentic, self-directed lives.

4. The Psychology of the Artist

One of Rank’s most enduring contributions was his exploration of the psychology of art and the artistic personality. In Art and Artist, he analyzed the creative process and the unique dynamics of the artist’s life as a model for human development.

For Rank, the artist was the ultimate example of an individual who asserts their creative will in the face of life’s limits and uncertainties. Through their work, artists confront the fundamental anxieties of existence – the fears of life and death, isolation and meaninglessness. They transmute these fears into something meaningful and beautiful.

Rank was fascinated by the paradoxes of the artistic personality. He saw artists as driven by a deep need to express their individuality and leave a lasting mark on the world. At the same time, they often struggled with feelings of inferiority, alienation, and a longing for acceptance and immortality through their creations.

In his case studies of famous artists like Wagner and Nietzsche, Rank traced how these conflicts shaped their lives and work. He examined their relationships with mentors, muses, and audiences as part of the never-ending struggle between separation and union, individuation and dependence.

Rank believed that studying artists could illuminate universal aspects of the human condition. We are all engaged in the creative project of shaping our identities and searching for meaning in the face of existential realities. We all grapple with the competing needs for self-expression and connection, originality and belonging.

At its best, Rank believed, the artistic life could serve as a model for authentic living. By embracing their creative will and facing life’s challenges with honesty and courage, artists could inspire us to do the same. They could point the way toward a life of greater freedom, purpose, and aliveness.

Rank’s ideas about art and creativity have had a lasting influence on psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology, and the study of high ability. His emphasis on the heroic journey of individuation and self-expression anticipated later research on motivation, flow states, and the personality traits of creative individuals.

5. Life Fear and Death Fear

At the core of Rank’s understanding of the human condition was the concept of life fear and death fear. He saw these twin anxieties as the fundamental challenge every individual must face in the journey toward selfhood and authenticity.

Life fear, for Rank, was the dread of having to confront life as an isolated, self-responsible individual. It was the anxiety of embracing the challenges and possibilities of existence, of having to rely on one’s own will and judgment in a world of uncertainty and struggle.

Death fear, on the other hand, was the terror of nonbeing – the knowledge that we are finite creatures whose lives are inherently fragile and transitory. It was the ultimate threat to our sense of meaning and permanence in the face of an indifferent universe.

Rank believed that much of human behavior and culture could be understood as attempts to deny or transcend these twin fears. Our drive for success, power, and immortality through our creations; our urge to lose ourselves in love, groups, and beliefs; our need for heroes and gods to save us – all reflect the ongoing struggle with life and death anxiety.

The neurotic, for Rank, was an individual who was overwhelmed by these fears and unable to face them constructively. They might cling to dependencies and illusions of safety, avoiding the challenges of separation and autonomy. Or they might adopt a grandiose, self-aggrandizing style, denying their vulnerability and finitude.

The journey of therapy, in Rank’s view, was about helping individuals confront their life fear and death fear more consciously and courageously. It was about supporting them in embracing the challenges of independent living while also accepting the realities of their mortal condition.

This required what Rank called “the courage to be” – the willingness to affirm one’s existence in the face of uncertainty and pain, to choose life and meaning despite the knowledge of death. It meant developing the strength to love knowing loss, to create knowing destruction, to connect knowing separation.

For Rank, this capacity to face life and death with open eyes was the hallmark of psychological maturity and health. It represented a heroic stance toward existence – an affirmation of life in all its beauty and tragedy, its ecstasy and anguish.

Rank’s insights into life fear and death fear anticipated later developments in existential psychology and terror management theory. His ideas continue to inspire therapists and individuals grappling with the fundamental challenges of the human condition in an age of anxiety and uncertainty.

6. Therapy as Creative Education

In his break with classical psychoanalysis, Rank re-envisioned the therapeutic process as a creative, future-oriented dialogue aimed at helping individuals strengthen their will and find their own path in life. He saw therapy not as a cure for mental illness but as a kind of existential education.

For Rank, the key task of therapy was to support patients in separating from old dependencies, assumptions, and patterns that were limiting their growth. It was about awakening their potential for self-determination and helping them take responsibility for shaping their own lives.

This required a new kind of therapeutic relationship, one centered on the patient’s creative will rather than on the authority of the analyst. Rank emphasized the importance of the “here-and-now” encounter between therapist and patient, the living reality of their mutual influence and collaboration.

The therapist, in Rank’s view, was not a detached expert interpreting the patient’s unconscious but an active partner in an ongoing dialogue. Their role was to listen empathically, mirror the patient’s experience, and offer perspectives that could expand their sense of possibility and choice.

At the same time, Rank believed the therapist needed to be willing to challenge the patient’s evasions and illusions, to confront them with the realities they were denying or avoiding. This included the realities of the therapeutic relationship itself – the transference longings, resistances, and anxieties that arose in the process.

The goal of this confrontation was not to break the patient’s will but to strengthen it – to help them face difficult truths and take responsibility for their own feelings and actions. It was a way of inviting them into a more authentic, alive relationship with self and others.

Ultimately, for Rank, therapy was a kind of creative apprenticeship. It was an opportunity for patients to discover and develop their own voice, values, and vision for their lives. By wrestling with the fundamental questions of existence in the context of a supportive yet challenging relationship, they could grow in their capacity for love, work, and self-realization.

Rank’s ideas about the therapeutic process had a profound influence on the development of humanistic, existential, and relational approaches to psychotherapy. His emphasis on the here-and-now encounter, the patient’s creative will, and the growth-promoting power of the therapeutic relationship anticipated later research on common factors in effective therapy.

7. Legacy and Influence

Otto Rank’s original and wide-ranging ideas had a significant impact on the development of psychotherapy, psychology, and the human sciences in the 20th century. Although his break with Freud and the psychoanalytic establishment marginalized him for a time, his influence continued to spread through his writings, teachings, and the work of his students and admirers.

Some of the key thinkers and movements influenced by Rank include:

- Humanistic psychology: Rank’s emphasis on the creative potential of the individual, the importance of the will and self-determination, and the growth-oriented nature of the therapeutic relationship were key influences on founders of humanistic psychology like Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow, and Rollo May. His ideas about art, love, and the human condition also resonated with humanistic thinkers.

- Existential therapy: Rank is often considered one of the pioneers of existential psychology and therapy alongside figures like Ludwig Binswanger and Viktor Frankl. His focus on life and death anxiety, the need for meaning and purpose, and the challenges of authentic living anticipated central themes in existential thought.

- Gestalt therapy: The founders of Gestalt therapy, Fritz and Laura Perls, were deeply influenced by their contact with Rank and his ideas. Rank’s emphasis on the here-and-now encounter, the creative function of anxiety, and the importance of separation and individuation can be seen in the theory and practice of Gestalt therapy.

- Object relations theory: Although Rank’s break with Freud initially led to his ideas being rejected by most psychoanalysts, his focus on early mother-child dynamics, pre-oedipal development, and separation-individuation processes anticipated later developments in object relations theory by thinkers like Melanie Klein and Margaret Mahler.

- Interpersonal psychoanalysis: Rank’s emphasis on the actual relationship between therapist and patient, the mutuality of the therapeutic encounter, and the curative power of new experience in the present moment were key influences on the interpersonal school of psychoanalysis developed by thinkers like Harry Stack Sullivan and Karen Horney.

- Attachment theory: While not a direct influence, Rank’s ideas about the formative impact of early bonding and separation experiences, the lifelong significance of the mother-child relationship, and the role of dependence and autonomy in development anticipated later research and theorizing in attachment theory by John Bowlby and others.

Beyond the field of psychology, Rank’s ideas about creativity, will, and the cultural role of myth and art have continued to inspire thinkers and practitioners in diverse fields. His writings on the hero’s journey of individuation, the psychological functions of religion, and the creative power of ideologies have influenced figures like Ernest Becker, Joseph Campbell, and Rollo May.

As the existential and humanistic traditions Rank helped to inspire have grown in influence, his ideas have gained renewed attention and appreciation. His prescient insights into birth, death, creativity and the search for meaning seem more relevant than ever in our age of anxiety and uncertainty.

Engaging with Rank’s multidimensional legacy invites us to reconnect psychology with the great philosophical and spiritual questions of human existence. It challenges us to place the lived experience of the individual – their hopes, fears, and strivings for authentic selfhood – at the center of our therapeutic and theoretical concerns.

In an era of medicalization, manualization, and quick-fix treatments, Rank’s vision of therapy as a creative, transformative journey of education and individuation remains a vital reminder of the deeper potentials of the healing relationship. His ideas continue to inspire new generations of therapists and thinkers seeking a more humane, artful, and existentially-grounded approach to understanding and alleviating human suffering.

At the same time, Rank’s work embodies the open-ended, ever-evolving spirit of psychological inquiry. He saw theories not as fixed dogma but as provisional tools for grappling with the complexities of the psyche and the human condition. Even as we learn from his insights, he invites us to move beyond them – to create new frameworks that address the realities and challenges of our time.

As we enter a world of accelerating change, dislocation, and uncertainty, Rank’s call to embrace our creative will in the face of anxiety seems more urgent than ever. In a time of fading inherited meanings and multiplying existential threats, his conception of the heroic journey of individuation offers a source of inspiration and guidance.

Engaging with Rank, we are challenged to envision an psychology that is adequate to the full range of human possibility and struggle – a discipline that reckons unflinchingly with the depths of our existential condition while affirming the resilience of the human spirit. Such a psychology would aim not merely to describe behavior or reduce symptoms, but to support the fundamental human task of creating meaning and realizing our potential for freedom, relatedness, and growth.

This is the unfinished project that Rank’s life and work calls us to take up anew – the ongoing quest to fathom the mysteries of the psyche and the self, to alleviate suffering and awaken the creative energies of life. As scholars, therapists, and seekers, we are invited to bring our own will and imagination to this great undertaking – to participate in the never-ending work of psychological and cultural renewal.

In this spirit, engaging with Rank becomes an occasion for our own creative individuation – an opportunity to confront the questions that animate our lives and to find our own voice in the conversation of ideas. As we grapple with his insights and challenges, we are called to become authors of our own psychological destinies, to take responsibility for the theories and practices that shape our world.

0 Comments