Existential Psychotherapy and the Human Condition

1. Introduction: Rollo May and the Existential Approach

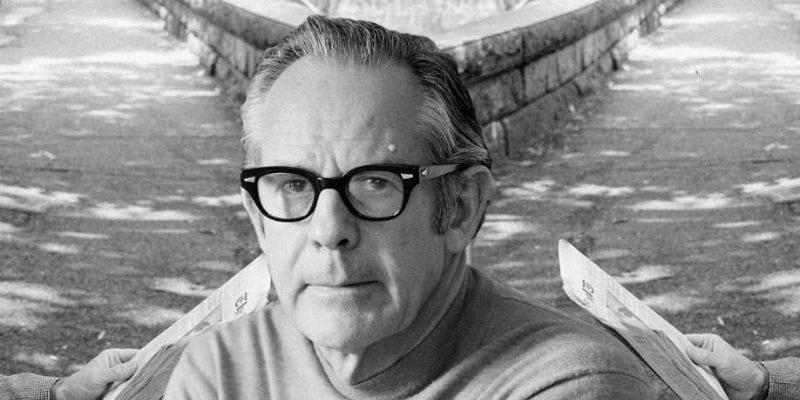

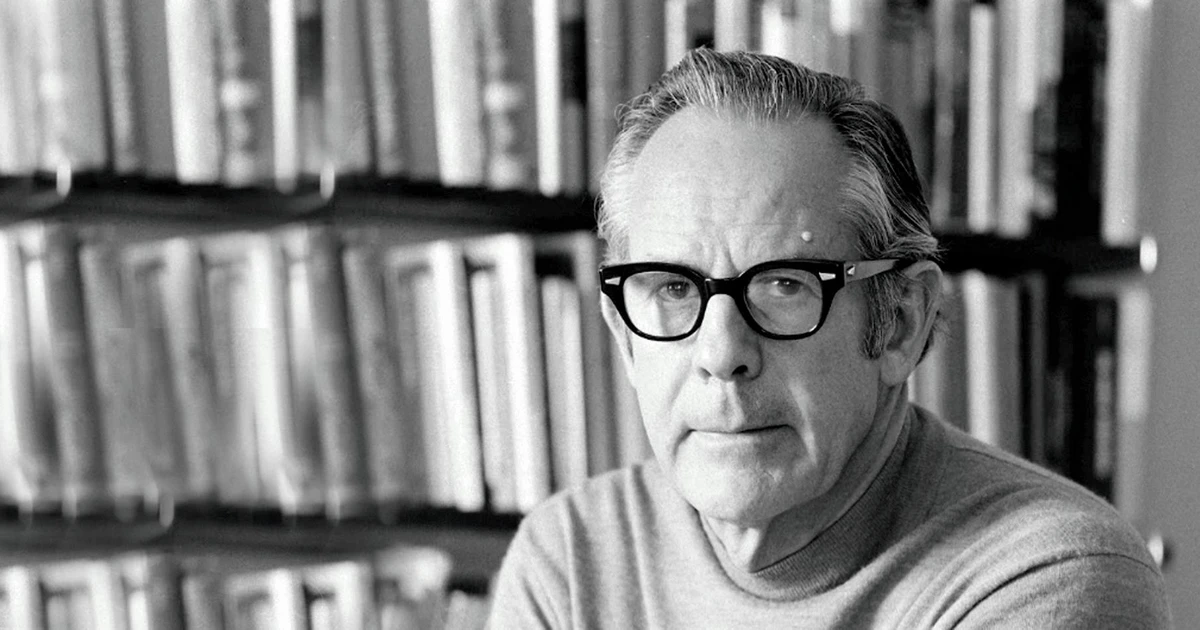

Rollo May (1909-1994) stands as one of the most influential figures in American psychology, renowned for introducing existential psychology to the United States and reshaping therapeutic approaches through his integration of philosophy, psychology, and profound human insight. Just as Robert Moore would later bring archetypal psychology into mainstream consciousness, May bridged European existential philosophy with American clinical practice, creating a therapeutic approach that addressed the deepest questions of human existence. May’s journey was not merely intellectual but deeply personal, as his own confrontation with mortality through tuberculosis led him to discover the existential roots of anxiety and human suffering.

May’s work represents a significant departure from the mechanistic and reductionist approaches that dominated psychology in his time. Rather than viewing humans as merely responding to drives or environmental conditioning, May emphasized human freedom, choice, responsibility, and the search for meaning. His approach treats each person as a unique being-in-the-world, struggling with the fundamental questions of existence: How do I live authentically? How do I face my freedom? How do I create meaning in a world that often seems meaningless?

This essay explores the theories and ideas of Rollo May, examining his contributions to existential psychology, his understanding of human nature, and the enduring relevance of his work for understanding the human condition in contemporary times. We use Rollo May’s ideas in Alabama at our therapy practice.

2. Life and Influences: The Making of an Existential Psychologist

2.1 Biographical Foundations

Rollo Reese May was born in 1909 in Ohio and grew up in Marine City, Michigan. His early family life was marked by tension and discord, which likely influenced his later interest in human anxiety and psychological distress. After completing his undergraduate studies in English at Oberlin College in 1930, May joined a group of artists traveling to Europe, where he studied local art in Poland and eventually took a teaching position at the American College in Salonika, Greece.

During this formative period in Europe, May was introduced to the works of European existentialists and attended summer school taught by Alfred Adler, though he found Adler’s theories somewhat simplistic. Upon returning to the United States, May pursued theological studies at Union Theological Seminary, where he formed a lifelong friendship with the existential theologian Paul Tillich, who introduced him to the works of Kierkegaard and Heidegger.

May’s path took a significant turn when he contracted tuberculosis in his late 30s. During his extended stay at Saranac Sanitarium in upstate New York, May had a profound realization that would shape his entire career. While reading the works of existentialist philosophers, particularly Søren Kierkegaard, May discovered that his own profound anxiety had more to do with the existential dread of nonbeing than with Freudian concepts of libido or drive theory. This insight became the foundation for his existential approach to psychology.

2.2 Intellectual Influences

May’s thought was shaped by a rich tapestry of influences from philosophy, psychology, theology, and literature. From European existentialism, particularly the works of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Heidegger, May absorbed the emphasis on individual existence, freedom, and authentic living. The existentialist focus on confronting the givens of existence—death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness—became central to his therapeutic approach.

From psychoanalytic thought, May drew upon Freud’s understanding of the unconscious, but reinterpreted it through an existential lens. He considered Otto Rank to be the most important precursor of existential therapy, appreciating Rank’s emphasis on the will and creativity. May once wrote, “I have long considered Otto Rank to be the great unacknowledged genius in Freud’s circle.” May also drew influence from North American humanism and sought to reconcile existential psychology with other philosophies, especially Freud’s.

May was also deeply influenced by humanistic psychology, particularly the work of Abraham Maslow, though he felt that humanistic approaches sometimes failed to grapple sufficiently with the darker dimensions of human existence. His approach would ultimately bridge humanistic psychology’s emphasis on growth and self-actualization with existentialism’s unflinching confrontation with anxiety, guilt, death, and the struggles of freedom.

3. May’s Core Theoretical Concepts

3.1 Being-in-the-World (Dasein)

Central to May’s existential psychology is the concept of Dasein, or “being-in-the-world.” May viewed each person as having “an inherent need to exist in the world into which we are born, and to achieve a conscious and unconscious sense of ourselves as an autonomous and distinct entity.” This being-in-the-world comprises three simultaneous and interrelated modes: our physical and physiological environment (Umwelt), the social world of other people (Mitwelt), and the psychological world of our self, potentials, and values (Eigenwelt).

For May, authentic existence requires engagement with all three modes. The Umwelt corresponds to our biological needs and the physical environment – the dimension that Freud emphasized in his theories. The Mitwelt encompasses our social relationships and interpersonal connections. The Eigenwelt refers to the relationship with oneself – self-awareness, values, and personal meaning. May argued that psychological health requires balance and integration across these three dimensions of existence.

Unlike theorists who focus predominantly on one aspect of human experience, May insisted that all three modes must be given equal emphasis to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the human personality. This holistic approach aims to overcome the fragmentation often found in more reductive psychological theories.

3.2 Anxiety and Its Meaning

Perhaps May’s most significant contribution was his reframing of anxiety from a merely pathological symptom to an ontological experience fundamental to human existence. Through his personal battle with tuberculosis, May came to recognize that anxiety had far more to do with “the dread of nonbeing, as described by such existentialists as Kierkegaard, than with the mechanical and metaphysical construct of libido.”

For May, anxiety differs from fear in that fear has a specific object, while anxiety is a response to a threat to the values one identifies with existence. Normal anxiety is proportionate to the threat and can be used constructively to confront the situation. Neurotic anxiety, on the other hand, is disproportionate, typically unconscious, and leads to avoidance behaviors.

May argued that anxiety cannot and should not be eliminated entirely, as it is inherent to human freedom and growth. Instead, the therapeutic goal is to help individuals develop the courage to face their anxiety constructively and use it as a catalyst for authentic living. May wrote extensively on this topic in his influential book “The Meaning of Anxiety” (1977), which remains one of his most significant contributions to psychological literature.

3.3 Freedom, Destiny, and Responsibility

Existential psychology places freedom at the center of human experience. May emphasized that existential psychology focuses on “freedom and destiny in regard to searching for the meaning of anxiety in a patient.” A person desires “freedom of the mind and body” and that an existentialist approach could help a person understand the whole version of themselves.

However, freedom for May is always situated within the context of destiny – the givens of our existence that we cannot change, such as our biological makeup, historical context, and inevitable death. The human task is to exercise freedom responsibly within the limitations of destiny. This creates an existential tension that many people try to escape by denying either their freedom (leading to conformity and deterministic thinking) or their limitations (leading to narcissistic fantasies of omnipotence).

May argued that psychological health requires acknowledging both our freedom and our limitations, and accepting responsibility for the choices we make within these parameters. The therapist’s role is to help patients recognize how they have limited their freedom through unexamined choices and defenses, and to encourage them to reclaim their capacity for conscious choice and responsibility.

3.4 The Daimonic

May introduced the concept of the daimonic to describe the natural functions that have the power to take over the whole person. A key aspect of the therapeutic process involves helping patients “integrate their daimonic into consciousness, recapture their lost will, take responsibility for their own lives, and make choices that lead to the fulfillment of their own innate potentials.”

The daimonic is neither good nor bad in itself but becomes destructive when the personality is too weak to integrate it. For example, anger is a natural human emotion that, when consciously integrated, can provide energy for setting boundaries and fighting injustice. However, when unintegrated, it can erupt destructively as rage or violence, or be turned inward as depression.

May’s understanding of the daimonic offers a more nuanced view of human destructiveness than traditional notions of evil or psychopathology. It recognizes that the same energies that can lead to creativity and vitality can also, when unintegrated, lead to destruction and suffering. The goal of therapy is not to eliminate the daimonic forces but to help the individual develop a strong enough center to integrate them constructively.

3.5 Love and Will

In his book “Love and Will” (1969), May addressed the crisis of meaning in modern society by exploring the dialectical relationship between love and will. He observed that contemporary culture had separated these two fundamental human capacities, with love often reduced to sentimental feelings or sexual desire, and will degraded to mere willpower or control.

May argued that love without will lacks the capacity for sustained commitment, while will without love becomes manipulative power. Authentic love requires the will to extend oneself for the growth of another, and genuine will needs the empathy and care that love provides. By reconnecting love and will, individuals can overcome the apathy and alienation characteristic of modern life and engage in meaningful, committed relationships and projects.

Through this work, May “emphasized the role of anxiety, creativity, love, and will in shaping the human condition and the therapeutic process.” His approach “drew on a range of philosophical, psychological, and anthropological insights, from existentialism to humanism to studies of art and culture.”

4. Existential Psychotherapy: Theory and Practice

4.1 Goals and Methods

The primary goal of existential psychotherapy as formulated by May is “to help patients recover their repressed Dasein, integrate their daimonic into consciousness, recapture their lost will, take responsibility for their own lives, and make choices that lead to the fulfillment of their own innate potentials.” As May expressed it, “The aim of therapy is that the patient experience his existence as real … which includes becoming aware of his potentialities, and becoming able to act on the basis of them.”

Unlike many therapeutic approaches that focus primarily on symptom reduction or behavioral change, existential therapy aims at a more profound transformation—helping individuals become more fully present and authentic in their existence. This involves confronting existential anxiety, accepting personal freedom and responsibility, engaging meaningfully with others, and finding purpose in life’s inherent struggles.

May described this unique aim of existential therapy: “Existential therapy is something radically different. The aims are to open the person up—to help this person become more sensitive to life, to beauty… Now that sounds a bit sentimental, I know, but it’s a very serious thing we need.”

4.2 The Therapeutic Relationship

May placed great emphasis on “the therapeutic relationship as a dialogical encounter” which has shaped the practice of existential and humanistic psychotherapy. “Therapists influenced by May strive to create a genuine, empathetic, and collaborative relationship with their clients, one that can facilitate deep self-exploration and transformation.”

For May, the therapeutic relationship is not merely a means to an end but an authentic human encounter. The therapist does not position themselves as a detached expert but as a fellow human being who accompanies the client in facing the challenges of existence. This requires presence, courage, and the willingness to be affected by the client’s struggles.

While May retained the Freudian term “patient,” he agreed that it was “misleadingly passive; changing one’s personality requires considerable effort and courage.” He emphasized that the “therapist must be sufficiently flexible to understand and use each patient’s constructs and language, rather than seeking to impose a single theoretical framework on all humanity.”

4.3 Therapeutic Techniques

In terms of specific techniques, May was procedurally eclectic. He recognized that therapists might draw from various approaches (e.g., Freudian, Rogerian) while maintaining an existential orientation. This flexibility reflects May’s belief that techniques should serve the deeper aim of helping clients experience their existence more authentically.

May was critical of what he called therapeutic “gimmicks”—techniques that treat isolated symptoms without addressing the whole person in their existential situation. May believed that modern psychotherapy was “branching away from its original founders: Freud, Jung, Rank, and Adler” and instead “isolated and ‘cured’ specific patient symptoms, called gimmicks.” He argued that “treating gimmicks puts the patient at a disadvantage by giving them a short-lasting fix, while distracting patients from their real problems.”

Instead, May advocated for a more holistic approach that explores the client’s being-in-the-world. This might involve examining how the client experiences their physical environment (Umwelt), social relationships (Mitwelt), and relationship with self (Eigenwelt). It also involves helping clients become aware of how they have constricted their freedom through neurotic patterns and defenses, and supporting them in making new, more authentic choices.

4.4 Stages of Development

May proposed a developmental framework that differs significantly from Freud’s psychosexual stages or Erikson’s psychosocial stages. May’s model included stages such as: “Innocence: an infant has few drives other than the will to live,” “Rebellion: a developing child seeks freedom but cannot properly care for herself,” and “Decision: a transitional stage during which a teenager or young adult makes decisions about his or her life, while seeking further independence from her parents.”

These stages reflect May’s existential emphasis on the developing person’s increasing freedom and responsibility. Unlike more deterministic developmental theories, May’s framework focuses on how individuals progressively encounter and cope with the existential givens of life—freedom, isolation, meaninglessness, and death.

5. May’s Contributions to Understanding Anxiety and Mental Health

5.1 The Existential Basis of Anxiety

May’s most enduring contribution may be his reframing of anxiety from a merely pathological symptom to an ontological condition inherent to human existence. Through his personal confrontation with mortality during his tuberculosis, May came to understand anxiety as the experience of being aware of the possibility of nonbeing—both literal nonbeing (death) and symbolic nonbeing (meaninglessness, isolation, loss of identity).

In the existential approach, anxiety is understood in relation to “four primary givens of existential therapy: freedom of choice, isolation, the inevitability of death, and meaninglessness.” Rather than focusing solely on the human dilemma in modern society, “existential therapy focuses on freedom and destiny in regard to searching for the meaning of anxiety in a patient.”

May distinguished between normal anxiety—a proportionate response to a genuine threat to one’s values or existence—and neurotic anxiety, which is disproportionate and typically unconscious. The goal of therapy is not to eliminate anxiety entirely (which would be impossible and undesirable) but to help the individual confront it consciously and use it constructively. Normal anxiety can be a catalyst for growth, creativity, and authentic living when faced with courage.

5.2 Modern Forms of Psychopathology

May’s existential psychology sought “to explain such modern forms of psychopathology as apathy and depersonalization” that traditional psychological approaches often failed to adequately address. May was particularly concerned with the psychological consequences of modernity—alienation, meaninglessness, and the loss of community and tradition.

For May, many psychological disorders could be understood as responses to the existential challenges of modern life. Depression might reflect an avoidance of the pain of existence or a loss of meaningful engagement with the world. Anxiety disorders could represent unsuccessful attempts to cope with the dread of nonbeing. Compulsive behaviors might serve to distract from existential anxiety or create an illusion of control in a world experienced as chaotic.

May’s approach to psychopathology differs from more medicalized models in that it views symptoms not merely as biological dysfunctions but as expressions of the individual’s struggle with the fundamental challenges of existence. This more humanistic perspective allows for a deeper understanding of suffering and more meaningful interventions that address the person’s whole being-in-the-world.

5.3 Creativity, Love, and Authenticity as Paths to Health

While May took the darker aspects of human existence seriously, he also emphasized the positive capacities that enable us to live meaningfully despite the existential givens. Creativity, love, and the courage to be authentic are central to psychological health in May’s framework.

Creativity allows us to bring something new into being, affirming our freedom and capacity to shape our world. Love enables us to transcend our isolation and connect meaningfully with others. Authenticity—living in accordance with our deepest values and potentials—provides an antidote to the depersonalization and conformity of modern society.

May emphasized that existential therapy aims “to open the person up—to help this person become more sensitive to life, to beauty,” highlighting the positive, life-affirming aspects of his approach despite its unflinching confrontation with life’s difficulties.

6. Cultural Analysis and Social Critique

6.1 The Crisis of Meaning in Modern Society

May was deeply concerned with the psychological impact of modernity and offered penetrating cultural criticism alongside his clinical insights. He observed that technological progress and material abundance had not led to greater psychological well-being but often to increased alienation, anxiety, and meaninglessness.

In works like “Man’s Search for Himself” (1953) and “The Courage to Create” (1975), May analyzed how modern society had undermined traditional sources of meaning and identity without providing adequate replacements. The decline of religious certainty, community bonds, and shared cultural narratives left many individuals adrift, unsure of how to find purpose in an increasingly complex, fragmented world.

For May, this crisis of meaning contributed to a range of social problems, from escapism through drugs and consumerism to ideological extremism and violence. He saw many of these issues as attempts to flee from the anxiety of freedom and the responsibility of creating meaning in one’s life.

6.2 Power, Violence, and Social Justice

In “Power and Innocence” (1972), May explored the relationship between power, violence, and human psychology. He argued that power is a fundamental aspect of being human—the capacity to affect and be affected, to cause effects in one’s world and in others. When healthy power is blocked or denied, it can transform into violence and destructiveness.

May believed that many social problems stemmed from misdirected or repressed power. Those who feel powerless in constructive ways may seek power through violence, domination, or manipulation. Similarly, idealistic attempts to deny the role of power in human relationships can lead to naive political approaches that ultimately fail or backfire.

For May, a more just society would require acknowledging the reality of power while channeling it constructively. This means creating social conditions where individuals can exercise meaningful agency in their lives while respecting the freedom and dignity of others. It also means developing the psychological maturity to handle power responsibly, which he saw as an essential aspect of adult development.

6.3 Technology, Alienation, and the Future of Humanity

May was among the first psychologists to seriously consider the psychological impact of technological advancement. While appreciating technology’s benefits, he warned of its potential to diminish authentic human experience and exacerbate alienation.

He observed how technology had contributed to the mechanization of human relationships, the acceleration of life’s pace, and the weakening of direct experience. These changes, while offering conveniences, threatened to undermine the depth and meaning of human existence. May was particularly concerned about how technology might distance us from the existential realities of life—pain, death, anxiety, and the struggle for meaning—that ultimately provide the context for authentic living.

Rather than rejecting technology outright, May advocated for a more mindful approach that would preserve human values and authentic experience. This would require developing what he called an “inner gyroscope”—a strong sense of self and values that could navigate technological society without becoming lost in its distractions and demands.

7. Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

7.1 Influence on Psychology and Psychotherapy

“By bringing the insights of existential philosophy to bear on the concrete challenges of clinical practice, May helped to humanize and deepen the therapeutic enterprise. His emphasis on creativity, courage, and the search for meaning in the face of life’s existential givens continues to resonate with therapists and clients alike.”

May’s work has significantly influenced the development of humanistic and existential psychotherapies, but his impact extends beyond these specific schools. Elements of his thinking have been incorporated into a range of therapeutic approaches, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, narrative therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions. His emphasis on meaning, choice, and authentic living resonates with contemporary positive psychology’s focus on well-being and the good life.

May’s “contributions have significantly shaped modern psychological practice, particularly in the realms of existential and humanistic therapy. His emphasis on understanding existential themes has broadened psychotherapy’s scope, offering more nuanced and holistic approaches to mental health.”

7.2 Relevance to Contemporary Issues

Despite the decades that have passed since May’s major works were published, his insights remain remarkably relevant to the psychological challenges of our time. In an era of rapid technological change, global connectivity, and increasing complexity, many individuals struggle with the same existential questions that May addressed—questions of meaning, identity, freedom, and authentic connection.

“As the field of psychology continues to evolve, May’s insights remain as relevant as ever. In a world marked by rapid change, dislocation, and the erosion of traditional sources of meaning, the existential questions that May grappled with have only become more urgent.”

May’s analyses of anxiety, alienation, and the search for meaning speak directly to contemporary concerns about rising rates of depression, anxiety disorders, and “diseases of despair.” His cultural critiques anticipate many current debates about the psychological impact of digital technology, consumer culture, and the erosion of community bonds. And his emphasis on creativity, courage, and personal responsibility offers valuable resources for those seeking to live meaningfully in challenging times.

7.3 Criticisms and Limitations

Despite his significant contributions, May’s work has not been without criticism. May has been “criticized for theoretical confusions and contradictions, failing to adhere to a consistent set of constructs, an inadequate explanation of the causes and dynamics of neurosis, a lack of originality, and a lack of scientific rigor.” Some have found his concepts too abstract or difficult to operationalize for empirical research.

May’s “existential approach to psychology has sparked debate due to its abstract nature and philosophical underpinnings. Critics argue for more empirical grounding in psychological practice, while supporters find deep value in the existential perspective.”

From a contemporary perspective, May’s work might also be criticized for insufficient attention to cultural, gender, and socioeconomic factors that shape individual experience. While he acknowledged social dimensions of existence, his focus on universal existential givens sometimes overshadowed the specific contexts that condition how these givens are experienced.

Despite these limitations, May’s work remains valuable for its depth, humanity, and integration of philosophical insight with clinical practice. His willingness to engage with the most profound questions of human existence has ensured his enduring relevance in a field sometimes prone to reductionism and oversimplification.

8.The Enduring Significance of Rollo May

Rollo May stands as a pivotal figure in the history of psychology who bridged the worlds of European existential philosophy and American clinical practice. Through his personal journey, scholarly work, and therapeutic innovation, he developed an approach to understanding the human condition that remains profoundly relevant today.

May’s existential psychology offers a compelling alternative to reductive approaches that view humans primarily in terms of drives, conditioning, or neurochemistry. By emphasizing freedom, choice, meaning, and the courage to face anxiety, he articulated a vision of psychological health that honors the complexity and depth of human experience. His insights into anxiety, love, creativity, and power continue to illuminate the challenges and possibilities of human existence.

In an age of increasing technological mediation, social fragmentation, and existential uncertainty, May’s work speaks with renewed urgency. His emphasis on authentic presence, meaningful connection, and the creative confrontation with life’s fundamental givens provides valuable guidance for those seeking to live with depth and purpose in challenging times. As we navigate the complexities of the 21st century, Rollo May’s existential vision offers a compass for the journey toward more authentic and meaningful lives.

Bibliography

May, R. (1953/1973). Man’s Search for Himself. Dell.

May, R. (1958/1967). Existence: A New Dimension in Psychiatry and Psychology. Simon & Schuster.

May, R. (1969). Love and Will. W.W. Norton & Company.

May, R. (1972). Power and Innocence: A Search for the Sources of Violence. W.W. Norton & Company.

May, R. (1975). The Courage to Create. W.W. Norton & Company.

May, R. (1977). The Meaning of Anxiety. W.W. Norton & Company.

May, R. (1983). The Discovery of Being: Writings in Existential Psychology. W.W. Norton & Company.

May, R. (1991). The Cry for Myth. W.W. Norton & Company.

Further Resources on May’s Work

Books

DeCarvalho, R. J. (1991). The Founders of Humanistic Psychology. Praeger.

Schneider, K., Bugental, J., & Pierson, J. F. (Eds.). (2001). The Handbook of Humanistic Psychology: Leading Edges in Theory, Research, and Practice. Sage Publications.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Institute and Archives

The Rollo May Collection at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The Existential-Humanistic Institute, which continues May’s legacy through training and education.

Lectures and Interviews

“Rollo May on Existential Psychotherapy” – A video dialogue on the practice of psychotherapy.

“The Human Dilemma” – May’s lecture on freedom and destiny in modern society.

Articles and Reviews

Journal of Humanistic Psychology – Contains numerous articles on May’s contributions and contemporary applications of his work.

0 Comments