The Architecture of Metaphor: Truth Beyond Literal Truth

Every effective therapist knows that sometimes the most profound truths arrive dressed as fiction. Metaphors are, in their essence, true lies—statements that are literally false yet psychologically, emotionally, and even neurologically accurate. When we say someone has a “broken heart,” we know cardiac tissue hasn’t fractured, yet this metaphor captures something essential about human suffering that medical terminology cannot touch.

Metaphors work because our minds are not filing cabinets storing discrete facts, but rather meaning-making systems that understand through pattern, relationship, and felt sense. The cognitive linguists Lakoff and Johnson demonstrated that our entire conceptual system is fundamentally metaphorical—we understand abstract concepts through embodied experience. We “fall” in love, “carry” burdens, and “breakthrough” barriers. These aren’t decorative language choices; they’re how consciousness itself navigates reality.

In trauma work, metaphors become particularly vital. Trauma often exists in realms beyond ordinary language—in the wordless territories of the amygdala and brainstem, in procedural memories encoded before speech developed, in experiences so overwhelming they shattered the narrative self. Here, literal truth fails us. We need true lies that can bridge the chasm between the unspeakable and the spoken, between fragmentation and integration.

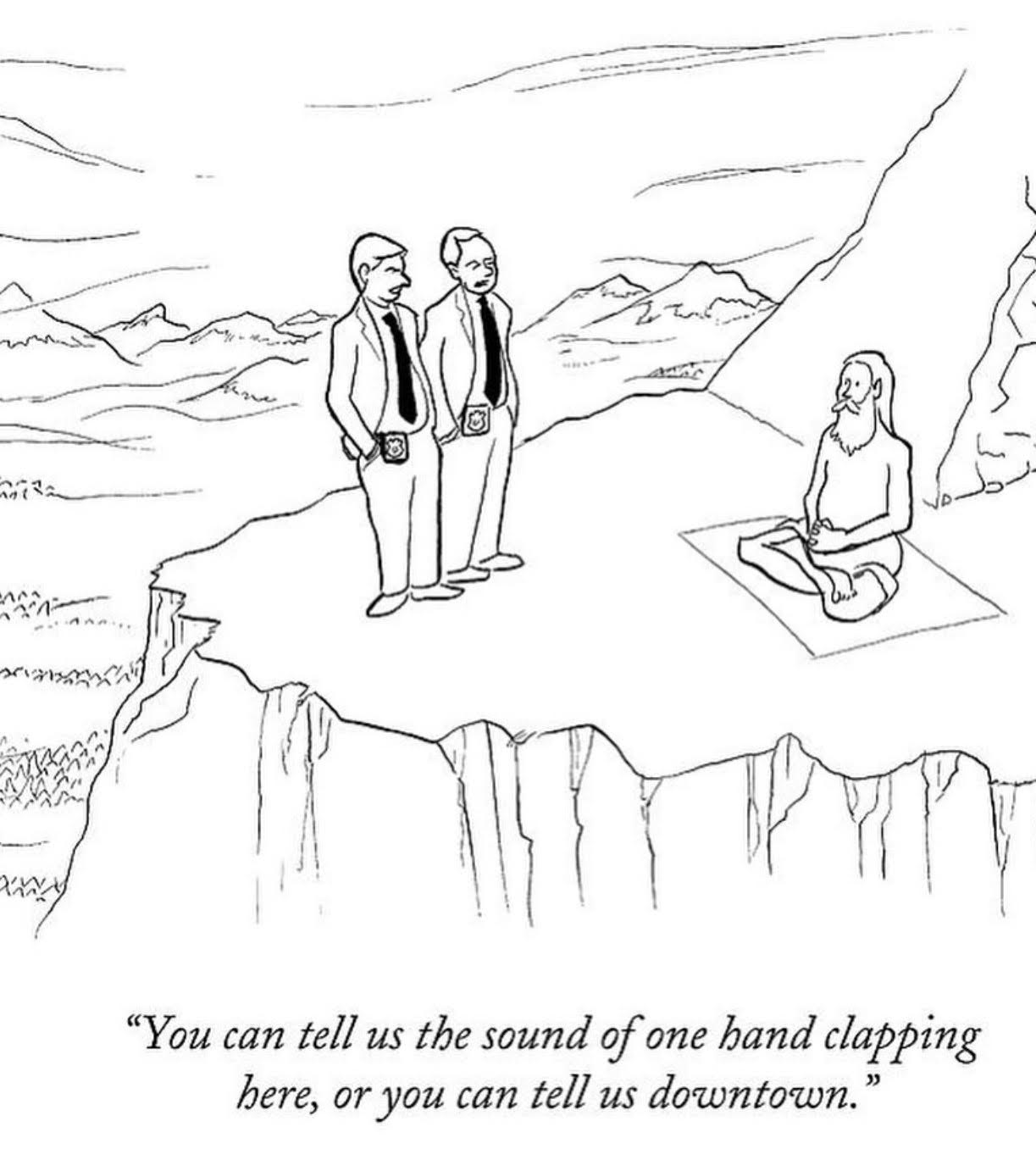

Zen Koans as Extended Metaphors for Consciousness

Zen koans—those enigmatic riddles like “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” or “Show me your original face before you were born”—function as extended metaphors for consciousness itself. They are designed not to be solved but to dissolve the solver, to short-circuit the rational mind and create an opening for a different kind of knowing.

Consider the koan: “Two hands clap and there is a sound. What is the sound of one hand?” This isn’t merely a puzzle; it’s a metaphor for the nature of trauma and healing. Trauma often leaves us with “one hand clapping”—attempting to complete patterns that were violently interrupted, reaching for connections that were severed, trying to make meaning from experiences that defied meaning-making.

The koan doesn’t offer resolution in the conventional sense. Instead, it invites us to inhabit paradox, to find a third way beyond the binary of problem-solution. This mirrors the therapeutic process where healing doesn’t mean “solving” trauma but learning to hold seemingly impossible contradictions: being simultaneously broken and whole, vulnerable and resilient, changed forever yet still essentially ourselves.

The Tension of Opposites: Jung Meets Trauma Therapy

Carl Jung understood that psyche naturally generates oppositions—conscious and unconscious, persona and shadow, animus and anima. He saw psychological health not as choosing one side but as maintaining creative tension between polarities, what he called the “transcendent function.” This concept finds remarkable resonance with both Zen philosophy and modern trauma therapy.

Trauma creates its own painful polarities: hypervigilance alternating with dissociation, desperate attachment swinging to fierce independence, the body experienced as both betrayer and sole truth-teller. Traditional approaches often tried to resolve these tensions by privileging one side—teaching only relaxation to the hypervigilant, only grounding to the dissociated. But contemporary trauma therapy, informed by interpersonal neurobiology and somatic approaches, recognizes that healing happens in the paradox itself.

Example: The Window of Tolerance Koan

Consider how the “Window of Tolerance” concept in trauma therapy functions like a koan. We tell clients they need to stay within their window (regulated) while simultaneously acknowledging that growth requires occasionally touching the edges (dysregulation). How can both be true?

Like the Zen student sitting with “What is Buddha?” and receiving the answer “Three pounds of flax,” the traumatized nervous system must learn that safety and growth, stability and change, are not opposites to be resolved but paradoxes to be inhabited. The koan-like instruction might be: “Stay safe enough to be unsafe, be stable enough to change.”

Example: The Freeze Response Paradox

The freeze response presents another koan-worthy paradox. In freeze, we are simultaneously absent and hyper-present, numb yet in agony, disappeared yet trapped in our bodies. Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing works with this paradox not by forcing choice but by “pendulating“—gently moving between polarities until a natural rhythm emerges.

This mirrors the Zen koan “Are you dead or alive?” asked of meditation students in deep samadhi. The answer isn’t choosing death or life but recognizing a state beyond both—what trauma therapists might call “aliveness” rather than mere survival.

Neurophenomenology: Where Brain Meets Being

Neurophenomenology—the marriage of neuroscience with first-person experience—reveals that these paradoxes aren’t just philosophical curiosities but are encoded in our neural architecture. The brain itself is built on paradox: approach and avoidance systems, default mode and task-positive networks, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems all functioning through dynamic opposition.

When we engage with koans or hold therapeutic paradoxes, specific neural networks activate. The anterior cingulate cortex, our conflict-monitoring system, lights up when encountering contradictions. But rather than resolving into frustration, sustained paradox engagement can lead to what neuroscientists call “transient hypofrontality”—a temporary quieting of the prefrontal cortex’s usual categorizing and analyzing, allowing other ways of knowing to emerge.

Subcortical Healing: The Wisdom Below Words

Trauma lives primarily in subcortical regions—the brainstem’s survival responses, the limbic system’s emotional memories, the cerebellum’s procedural patterns. These ancient brain regions don’t speak in words or logic; they communicate through sensation, image, and felt sense. This is why talk therapy alone often fails to heal trauma—we’re literally speaking the wrong language.

Zen koans, like effective trauma interventions, bypass the cortical narrator to engage these subcortical systems directly. When we sit with “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” the rational mind eventually exhausts itself, creating space for subcortical wisdom to emerge. Similarly, somatic trauma therapies invite clients to “drop below the story” into pure sensation, where healing happens at the level of neural integration rather than narrative understanding.

The Default Mode Network: Where Koans and Trauma Meet

The Default Mode Network (DMN), our brain’s “resting state” system, becomes particularly interesting in both koan practice and trauma healing. In trauma, the DMN often becomes hijacked by rumination and hypervigilance. But both meditation on koans and somatic trauma work can restore healthy DMN function—not by suppressing it but by allowing it to flow between focused attention and open awareness.

The koan “Who is carrying this corpse around?” directly points to DMN processes—our sense of self that persists across time, carrying our history. Trauma therapy asks a similar question: “Who are you beyond your trauma?” Both invite a loosening of rigid self-concepts while maintaining enough ego strength to function.

The Salience Network: Discovering What Matters

The Salience Network, anchored by the anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, determines what’s important enough to pay attention to. Trauma dysregulates this network, making everything (or nothing) seem threatening. Koans recalibrate salience by presenting problems that seem urgent but have no conventional solution, teaching the nervous system to hold importance lightly.

When a therapist asks, “What do you notice in your body right now?”—seemingly simple yet profoundly complex—they’re offering a koan to the salience network. What matters in this moment? The racing heart? The quiet breath? The space between them?

Integration: The Middle Way Through Trauma

The Buddha’s Middle Way—avoiding extremes of indulgence and asceticism—offers a template for trauma integration. We neither deny our wounding nor become identified with it. We acknowledge fragmentation while cultivating wholeness. We honor survival strategies while developing new responses.

This integration happens not through force but through what Dan Siegel calls “COAL”—Curiosity, Openness, Acceptance, and Love. These qualities emerge naturally when we stop trying to solve the unsolvable and instead learn to inhabit paradox with grace. The koan of trauma might be: “How do you heal what cannot be fixed?” The answer, like all good koan responses, is both impossible and inevitable: You heal by becoming large enough to hold both the wound and the wholeness.

The Ultimate Koan: Being Human

Perhaps the ultimate koan is consciousness itself—how does matter become aware? How does trauma, encoded in flesh and synapse, transform into wisdom? These questions have no answers in the conventional sense, yet we live the answers every day in our healing journeys.

When clients arrive shattered by trauma, carrying impossible contradictions, we don’t offer them solutions but something more valuable: companionship in paradox. We sit together with the koans of their experience until something shifts—not because we’ve solved anything but because we’ve expanded beyond the need for resolution.

The Zen master Dogen wrote, “Practice and enlightenment are one.” Similarly, in trauma therapy, the journey and destination merge. Each moment of staying present with difficult sensation, each breath taken in the face of activation, each choice to remain curious rather than conclusive—these are simultaneously the path and the arrival.

In the end, koans and trauma therapy share a secret: The paradoxes that seem to trap us are actually doorways. The opposites that tear us apart can become the dynamic tension that holds us together. The true lies of metaphor, whether in ancient Zen riddles or modern therapeutic frameworks, point us toward truths that transcend ordinary understanding—truths that can only be lived, embodied, and shared in the sacred space between one human consciousness and another.

0 Comments