Carl Jung’s The Red Book: A Journey into the Collective Unconscious

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), the renowned Swiss psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology, left an indelible mark on the field of depth psychology with his groundbreaking concepts of archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the process of individuation. These revolutionary ideas emerged not only from Jung’s extensive clinical observations and theoretical studies but also from a profound personal journey of psychological transformation that he meticulously documented in his magnum opus, The Red Book.

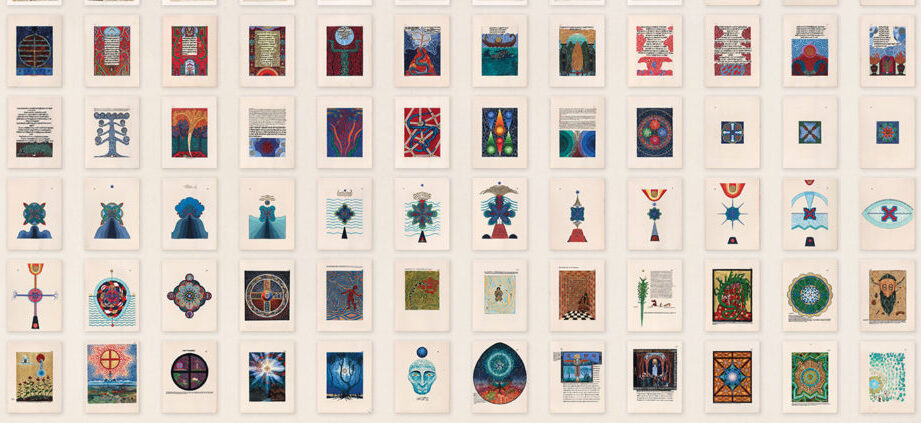

The Red Book, also known as Liber Novus (New Book), is a massive, illuminated manuscript that Jung created between 1913 and 1930. Filled with intricate calligraphy, stunning artwork, and vivid descriptions of his inner experiences, dreams, and visions, The Red Book provides an unparalleled window into the psyche of one of the most brilliant minds in psychology.

The Red Book is a monumental work that defies easy categorization or summary. Part personal diary, part mythological epic, part philosophical treatise, it offers a kaleidoscopic view of the human psyche in all its complexity and mystery. Through its vivid imagery, rich symbolism, and profound insights, The Red Book invites readers to embark on their own journey of self-exploration, to confront the shadows and potentials of their inner world.

As Jung himself wrote in the closing pages of The Red Book, “The way to your Self is the longest way and the hardest way. It is the way of your living soul, which is your true Self. May you succeed in your quest, may you come to realize your Self, may you arrive at your being, may you find your inner star, may you walk with its light, may you remain true to yourself. May your light shine!”

Cultural Projection and Anticipation: Jung’s Red Book as a Mirror of Modernity and Beyond

In The Red Book Jung is grappling with the fundamental tensions that characterized the early 20th century – a period marked by rapid industrialization, scientific advancement, and the erosion of traditional belief systems. In this context, Jung’s work can be understood as a microcosm of the broader cultural struggle between the classical values of order, harmony, and meaning, and the modernist impulse towards fragmentation, experimentation, and the questioning of established norms.

On one level, The Red Book is deeply rooted in the classical tradition, as evidenced by Jung’s extensive use of mythological and religious symbolism, his incorporation of elements from medieval manuscripts, and his overarching quest for wholeness and self-realization. The intricate mandala structures that recur throughout the work, for instance, can be seen as an attempt to restore a sense of unity and coherence in the face of the modern world’s increasing chaos and uncertainty.

At the same time, however, Jung’s approach in The Red Book is distinctly modernist in its emphasis on subjective experience, its exploration of the irrational and the unconscious, and its willingness to break with conventional forms of representation. The bold, expressive style of many of the paintings, the use of abstract and symbolic elements, and the incorporation of diverse cultural influences all reflect the experimental spirit of modernist art and thought.

In this sense, The Red Book can be understood as a kind of bridge between the classical and modernist worldviews – an attempt to negotiate the competing demands of tradition and innovation, order and chaos, the collective and the individual. Jung himself recognized this tension, writing in his autobiographical reflections, “I have had to make a virtue of necessity and find my way between the Scylla of academic science and the Charybdis of occultism.” (Memories, Dreams, Reflections, p. 197)

But perhaps the most remarkable aspect of The Red Book is the way in which it seems to anticipate the emergence of postmodernism and the crisis of meaning that would come to define the latter half of the 20th century. In his confrontation with the unconscious, Jung grappled with the very foundations of human knowledge and experience, questioning the stability of the self, the nature of reality, and the limits of language and representation.

This is particularly evident in the Incantations section of the work, where Jung engages in a kind of proto-postmodernist deconstruction of traditional forms of meaning-making. The fragmented, non-linear text, the juxtaposition of image and word, and the use of irony and self-reflexivity all prefigure the strategies that would later be adopted by postmodernist artists and thinkers in their challenge to the grand narratives of modernity.

Moreover, Jung’s emphasis on the role of the unconscious and the importance of symbolism and myth can be seen as a direct challenge to the rationalist and positivist assumptions of the modern era. By insisting on the primacy of the inner world and the power of the imagination, Jung anticipated the postmodern turn towards subjectivity, relativism, and the celebration of difference and plurality.

In this light, The Red Book emerges as a truly visionary work – not only in its exploration of the depths of the human psyche but also in its uncanny ability to foreshadow the cultural and intellectual developments that would shape the course of the 20th century and beyond. Jung’s insights into the archetypal patterns and psychological forces that underlie human experience, his recognition of the importance of myth and symbolism, and his willingness to confront the darkness and uncertainty of the modern world all contribute to the enduring relevance and power of this extraordinary work.

Of course, it would be a mistake to reduce The Red Book to a mere reflection of cultural trends or intellectual movements. At its core, the work remains a deeply personal and idiosyncratic creation – a testament to Jung’s own unique vision and his lifelong quest for self-knowledge and transformation. But by situating the work within its broader historical and cultural context, we can begin to appreciate the ways in which Jung’s journey into the unconscious was not merely a private affair but also a profound engagement with the larger forces that were shaping the modern world.

In many ways, The Red Book can be seen as a kind of warning or prophecy – a call to confront the darker aspects of human nature and the dangers of a world that had lost touch with its mythic and spiritual roots. Jung himself was acutely aware of the potential for destruction and chaos that lurked beneath the surface of modern civilization, and he saw his own journey into the unconscious as a necessary step towards healing the rift between the individual and the collective, the rational and the irrational, the conscious and the unconscious.

Origins and History:

The genesis of The Red Book can be traced back to a pivotal period in Jung’s life and career. In 1913, Jung underwent a dramatic break with his mentor and collaborator, Sigmund Freud, due to irreconcilable differences in their theoretical views. This split left Jung in a state of profound psychological crisis, as he grappled with feelings of disorientation, self-doubt, and the loss of his intellectual and emotional anchor.

During this turbulent time, Jung began experiencing a flood of vivid dreams, visions, and fantasies that he feared were signs of impending psychosis. Rather than suppressing or ignoring these disturbing experiences, Jung made the courageous decision to engage with them directly, using them as a catalyst for self-exploration and personal growth.

Jung started recording his inner experiences in a series of notebooks, which he referred to as his “Black Books.” These notebooks served as the raw material for what would eventually become The Red Book, a more polished and elaborate version of his psychological journey.

Over the course of sixteen years, Jung devoted himself to the creation of The Red Book, pouring his heart and soul into every page. He spent countless hours writing, painting, and illustrating, often working late into the night in a state of creative fervor. Jung referred to this process as his “confrontation with the unconscious,” a voluntary descent into the unknown depths of his psyche.

Despite the central role that The Red Book played in his personal and professional development, Jung never intended for it to be published during his lifetime. He considered it to be a private document, a personal record of his innermost thoughts and experiences. It wasn’t until many years after his death, in 2009, that The Red Book was finally published, thanks to the efforts of Jung’s family and a dedicated team of scholars led by Dr. Sonu Shamdasani.

How to Read the Red Book:

There are several methods, techniques, and approaches that can be helpful when reading and attempting to understand The Red Book by Carl Jung:

Amplification:

This is a technique often used in Jungian analysis, which involves exploring the cultural, mythological, and historical context of a symbol or image to enrich its meaning. When encountering a particular symbol or figure in The Red Book, research its significance in various cultural and religious traditions to gain a deeper understanding of its psychological implications.

Visual Analysis:

Pay close attention to the intricate illustrations and calligraphy throughout the book. Analyze the colors, forms, and symbols used in each image and consider how they relate to the accompanying text. Jung’s artwork often provides additional layers of meaning and insight into his psychological state and the archetypal themes he explores.

Comparative Analysis:

Compare and contrast the ideas and symbols in The Red Book with those in Jung’s later writings, such as Psychology and Alchemy, Answer to Job, and Aion. This approach can help you understand how the raw material of Jung’s visions was refined and integrated into his mature psychological theories.

Personal Reflection:

Use the book as a catalyst for your own personal growth and self-exploration. Reflect on how the themes and symbols in The Red Book relate to your own life experiences, dreams, and inner struggles. Consider keeping a journal to record your thoughts and insights as you read.

Dialogue with the Text:

Engage in an active dialogue with the book by asking questions, challenging assumptions, and considering alternative interpretations. Treat the book not as a fixed set of ideas but as a living document that invites ongoing exploration and discovery.

Scholarly Commentary:

Consult scholarly works and commentaries on The Red Book to gain additional perspectives and insights. Books like Sonu Shamdasani’s C. G. Jung: A Biography in Books, James Hillman’s Lament of the Dead, and Murray Stein’s Jung’s Red Book for Our Time can provide valuable context and analysis.

Group Discussion:

Join or form a study group or book club dedicated to reading and discussing The Red Book. Sharing your insights and hearing others’ perspectives can deepen your understanding and provide new avenues for exploration.

Meditative Reading:

Approach the book as a meditative text, reading slowly and contemplatively. Allow yourself to sit with the images and ideas that resonate with you, even if their meaning is not immediately clear. Trust in the power of the symbols to work on your unconscious and reveal their significance over time.

Characters and Symbols in the Red Book:

Philemon

Philemon, a wise old man with the horns of a bull, serves as a spiritual guide and guru figure throughout The Red Book. He engages Jung in philosophical dialogues and provides guidance on his journey through the unconscious. Philemon represents the archetypal Wise Old Man and acts as a mediator between Jung’s conscious mind and the deeper layers of the unconscious. Through his interactions with Jung, Philemon helps him navigate the challenges of individuation and interpret the meaning of his visions, fostering a deeper understanding of the psyche and the process of self-realization.

Jung’s painting of Philemon, created after 1924, showcases his developed artistic skills and attention to detail. The use of vibrant colors, precise linework, and the incorporation of mandala-like structures demonstrate Jung’s growing mastery of symbolic representation. Philemon’s central placement in the art, along with the use of a domed building and palm trees in the background, creates a sense of spiritual authority and wisdom. The inclusion of a domed building resembling the Tomb of Theodoric and the mosaic-like elements from the Tomb of Galla Placidia in Ravenna reflect Jung’s fascination with Byzantine art and its influence on his artistic expression.

Siegfried

Jung’s illustration of the ambush of Siegfried on the mountain path is rendered in a style reminiscent of popular historical literature of the period. The simplified layout and use of bold colors suggest Jung’s attempt to capture the essence of the scene rather than striving for realism. The central placement of Siegfried, with his shield aloft, creates a sense of drama and tension. The use of diagonal lines in the composition adds to the dynamic quality of the scene.

The image represents Jung’s confrontation with the hero archetype and the need to sacrifice the inflated sense of self to achieve psychological growth. The Siegfried myth, rooted in Germanic folklore, reflects the archetypal hero’s journey and its significance in the collective unconscious.

Salome

Salome, a young, beautiful, and seductive woman, appears in The Red Book as a figure who performs an erotic dance and tempts Jung with her allure. She demands the head of John the Baptist, a symbol of the ego’s attachment to morality and conventional wisdom. Salome represents the anima, the feminine aspect of Jung’s psyche, and embodies the power of the unconscious to both fascinate and destroy.

Through her actions and presence, Salome challenges Jung to confront and integrate his own feminine nature, a crucial step in the individuation process. Jung’s depiction of Salome as a demure young woman deviates from the more sensual and provocative representations common in the art of the time. This suggests Jung’s personal interpretation of the figure and its psychological significance

Elijah

Elijah, a blind prophet and father figure, engages Jung in discussions about the nature of God, prophecy, and the relationship between the human and the divine. As a symbol of the archetypal Father and the religious function of the psyche, Elijah challenges Jung to confront his own understanding of God and to differentiate between genuine spiritual experience and inflation. Through his dialogues with Elijah, Jung grapples with the role of religion and spirituality in the individuation process and the importance of maintaining a grounded, humble approach to the numinous.

Izdubar

Izdubar, a mighty Babylonian hero similar to Gilgamesh, seeks Jung’s help in his quest for immortality and faces various trials and challenges throughout The Red Book. As a representation of the archetype of the Hero and the ego’s journey towards self-realization, Izdubar’s story parallels Jung’s own individuation process. The hero’s confrontation with mortality and the limits of human power mirrors Jung’s own struggles and insights as he navigates the depths of the unconscious.

Jung’s representation of Izdubar, an early name for Gilgamesh, showcases his adaptation of ancient mythological figures into his own symbolic language. The use of a stylized, almost hieratic pose and the incorporation of a Minoan double-bladed ax demonstrate Jung’s eclectic approach to visual symbolism. The Gilgamesh epic, one of the oldest known literary works, reflects the universal themes of the hero’s journey, mortality, and the search for meaning, which Jung sought to integrate into his own psychological understanding.

The Red One

The Red One, a devilish, trickster-like figure with red skin, challenges Jung with riddles and paradoxes, tempting him to doubt his own understanding. As a symbol of the shadow, the rejected or repressed aspects of the personality, The Red One forces Jung to confront the darker, more chaotic aspects of his psyche. By engaging with this figure, Jung learns to integrate the shadow into his conscious understanding, a necessary step towards wholeness and self-acceptance.

The Serpent

The Serpent, a wise, oracular creature that speaks in cryptic riddles, provides Jung with enigmatic advice and challenges him to decipher its meaning. Representing the archetype of transformation and the kundalini energy of the unconscious, The Serpent guides Jung through the process of psychic death and rebirth necessary for individuation. Its presence highlights the importance of embracing change and allowing the old, limiting aspects of the self to be shed in favor of new growth and understanding.

Ka

Ka, an Egyptian concept of the vital essence or soul, is represented in The Red Book as a bird-like being that instructs Jung on the nature of the soul and its journey after death. As a symbol of the individual soul and its relation to the collective unconscious, Ka helps Jung understand the transpersonal aspects of the psyche and the continuity of the soul beyond the individual ego. This understanding is crucial for Jung’s later theories on the collective unconscious and the archetypal foundations of human experience.

Maria

Maria, a young woman who appears as a spiritual guide and anima figure, engages Jung in discussions about love, spirituality, and the path of inner development. Representing a higher, more integrated form of the anima, Maria guides Jung towards a greater understanding of the spiritual dimensions of the individuation process. Her presence illustrates the importance of embracing the feminine aspects of the psyche and integrating them with the masculine, rational mind in order to achieve wholeness and balance.

The Cabiri

The Cabiri, gnome-like figures associated with the ancient mysteries of Samothrace, challenge Jung with cryptic teachings and initiate him into their occult knowledge. As representatives of the archetypal forces of the collective unconscious and the transformative power of ancient wisdom traditions, The Cabiri guide Jung towards a deeper understanding of the universal patterns and principles underlying human experience. Their presence in The Red Book highlights the importance of engaging with the timeless wisdom of the past in order to navigate the challenges of the present and future.

The Magician Ha

The Magician Ha, a mysterious, shape-shifting sorcerer with powers of transformation, puts Jung through various magical trials and initiations, testing his resolve and understanding. Representing the archetypal Magician and the ego’s capacity for creative transformation, Ha challenges Jung to master the forces of the unconscious and to use them for the purpose of individuation and self-realization. Through his encounters with Ha, Jung learns to harness the power of the imagination and the creative potential of the psyche in service of his own growth and development.

Atmavictu

The image of Atmavictu showcases Jung’s experimentation with different artistic traditions, including elements of Navajo sand painting and Celtic art. The use of vibrant colors and intricate patterns demonstrates Jung’s growing interest in the symbolic potential of visual expression. The central placement of Atmavictu, along with the detailed border featuring various creatures and symbols, creates a sense of cosmic significance and interconnectedness. Jung’s incorporation of elements from diverse artistic traditions reflects his growing interest in comparative mythology and the universality of archetypal symbolism.

Mandala

Jung’s mandala on page 125 showcases his synthesis of traditional and avant-garde elements, combining a radiating golden mandala in the upper zone with a Swiss landscape rendered in a folk-art style below. The image is a synthesis of the classical. The juxtaposition of both modern and classical style and content show case a tension of the opposites between the old world and the new spiritual lessons Jung saw as inevitable transformations. One way to read this image is as a messiah figure bringing light and fire to a traditional world that cannot comprehend it.

Jung himself may be there messianic fire bringer but he may also have been seeing how new age spirituality would threaten and transform old heirarchies over the next few decades.

The division of the image into transcendental and mundane zones, along with the mediating figure of the yogi, creates a sense of balance and integration between the spiritual and the earthly realms. Jung’s use of the mandala form reflects his growing interest in Eastern spiritual traditions and their potential for psychological insight and transformation. The incorporation of the Swiss landscape demonstrates his commitment to grounding his psychological ideas in the context of his own cultural heritage.

Faces and Skulls

The final image in The Red Book, featuring faces arranged around a mandala morphing into skulls, showcases Jung’s experimentation with a style reminiscent of the Belgian Symbolist painter James Ensor. The use of a caricature-like approach and the juxtaposition of life and death elements create a sense of psychological and existential introspection. The circular arrangement of the faces and skulls, along with the mandala-like structure, evokes a sense of cyclicality and transformation. The use of skull imagery and the themes of life and death reflect the influence of Symbolist and Expressionist art movements, which sought to explore the deeper psychological and existential dimensions of human experience. The artwork anticipates similar styles of expressionism and illustration with roots in the 60s and cultural dominance in mainstream culture of the 70s.

Summary of The Red Book

Part 1: Liber Primus (The Way of What Is to Come):

The first part of The Red Book, titled Liber Primus, chronicles Jung’s initial forays into the realm of the unconscious. In a series of vivid fantasies and dialogues, Jung encounters a cast of inner figures, each representing different aspects of his psyche. These figures include the wise old man Philemon, the young girl Salome, the prophet Elijah, and the Germanic hero Siegfried, among others.

Allusions and Symbolism:

Throughout Liber Primus, Jung makes extensive use of mythological, religious, and literary allusions to convey the depth and complexity of his psychological experiences. The opening passages, in which Jung descends into the underworld of the psyche, draw heavily on the Greco-Roman myth of the hero’s katabasis, or journey to the underworld, as well as Dante’s Inferno from The Divine Comedy.

The figure of Philemon, who appears as a wise old man with the horns of a bull, evokes the ancient Greek god Dionysus, as well as the archetypal image of the Wise Old Man that recurs throughout world mythology. Philemon serves as Jung’s guide and interlocutor, helping him navigate the treacherous waters of the unconscious.

Jung’s encounter with the biblical figure Salome, who performs an erotic dance before asking for the head of John the Baptist, alludes to the story from the Gospels while also symbolizing the anima, Jung’s term for the feminine aspect of the male psyche. Salome represents the alluring yet dangerous power of the unconscious, the need to confront and integrate the repressed feminine side of the self.

The murder of Siegfried, the legendary Germanic hero, represents the ego’s necessary sacrifice of its heroic ideals and personas in order to achieve greater self-knowledge. By slaying the dragon of the unconscious and bathing in its blood, Siegfried attains a new level of invulnerability and wisdom. For Jung, this myth symbolized the painful but liberating process of letting go of the ego’s attachments and illusions.

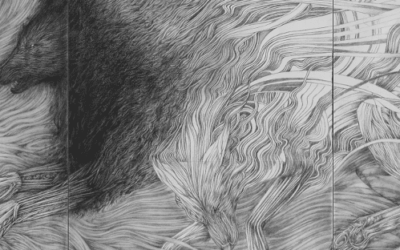

Artwork and Interpretation:

The artwork of Liber Primus is characterized by a raw, expressive style that vividly conveys the intensity and chaos of Jung’s inner experiences. The illustrations are often dark and unsettling, filled with violent, erotic, and grotesque imagery that reflects Jung’s confrontation with the shadow, the rejected or repressed aspects of the personality.

One of the most striking images in this section is the triptych of the giant Izdubar, a figure from Babylonian mythology. Jung depicts Izdubar as a towering, god-like being with a serpent coiled around his body, suggesting the archetype of the Self, the organizing principle of the psyche that encompasses both conscious and unconscious elements. The integration of the serpent, a ubiquitous symbol of the unconscious and the chthonic realm, hints at the process of individuation, the development of a more complete and authentic selfhood.

Another key image is the Eye of Horus, an ancient Egyptian symbol of protection, wholeness, and spiritual power. In Jung’s rendition, the Eye of Horus is surrounded by a mandala-like structure, representing the unity and balance of the Self. The image suggests the need for inner vision and insight, the ability to see beyond the illusions of the ego and perceive the deeper truths of the psyche.

The Sun God motif also appears repeatedly in Liber Primus, often in the form of a solar disc or a radiant figure. Jung’s fascination with solar symbolism was influenced by the work of contemporary scholars like Max Müller and James Frazer, who saw the sun as one of the earliest and most universal religious symbols. For Jung, the sun represented the archetypal image of the Self, the central source of light, life, and consciousness in the psyche.

Jung’s depiction of the hero slaying the dragon, a classic motif in mythology and folklore, takes on added significance in light of his solar symbolism. By conquering the dragon of the unconscious, the hero (representing the ego) is able to reclaim the hidden treasure of the Self, often symbolized by a golden sun disk or a luminous jewel. This process of heroic self-conquest and self-discovery lies at the heart of Jung’s concept of individuation.

Psychological Concepts:

Liber Primus laid the groundwork for many of Jung’s most important psychological concepts, which he would continue to develop and refine throughout his career. The encounters with inner figures like Philemon and Salome anticipate Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, the shared repository of human experience that manifests through universal symbols and archetypes.

Jung’s active engagement with these figures through dialogue and imagination demonstrates the technique of active imagination, a cornerstone of Jungian therapy. By engaging directly with the characters and images that emerge from the unconscious, Jung believed that individuals could tap into the hidden wisdom of the psyche and facilitate the process of self-realization.

The confrontation with the shadow, personified in figures like the Red One and the magician Ha, prefigures Jung’s emphasis on shadow work as a crucial aspect of psychological growth. By acknowledging and integrating the darker, less acceptable aspects of the personality, Jung argued that individuals could achieve a greater sense of wholeness and authenticity.

The theme of sacrifice and death, exemplified by the murder of Siegfried and the descent into the underworld, anticipates Jung’s conception of the ego-self axis. Jung believed that the ego, the center of conscious identity, must undergo a process of death and rebirth in order to align itself with the larger, transpersonal Self. This process of ego-transcendence is a key aspect of individuation, the lifelong journey of psychological and spiritual development.

Part 2: Liber Secundus (The Great Work):

The second part of The Red Book, Liber Secundus, marks a shift into a more mythological and visionary mode of expression. Jung’s fantasies take on an increasingly archetypal character as he encounters a host of figures from various world mythologies, including the Sumerian king Izdubar, the Gnostic prophet Simon Magus, and the divine child motif.

Allusions and Symbolism:

The title of Liber Secundus, “The Great Work,” is a direct reference to the alchemical magnum opus, the process of transforming base matter into the philosopher’s stone, the ultimate symbol of spiritual perfection and enlightenment. Jung uses alchemical symbolism extensively throughout this section to convey the deep, often paradoxical process of psychic transformation.

The figure of Abraxas, a lion-headed deity with a serpent’s tail, represents the union of opposites, the reconciliation of good and evil, masculine and feminine, conscious and unconscious. Abraxas serves as a powerful symbol of the Self, the totality of the psyche that transcends the dualistic categories of the ego.

The scenes with the prophet Elijah and his blind daughter Salome continue to explore the dynamics of the anima and the process of anima work, the integration of the feminine aspect of the psyche. Salome’s dance, which culminates in the beheading of John the Baptist, symbolizes the sacrifice of the ego’s attachment to rigid, moralistic attitudes in order to embrace the fluid, creative power of the unconscious.

The Gnostic figure Simon Magus, who engages in a series of mystical and magical practices, represents the archetype of the Magician, the ego’s capacity for creative manipulation of psychic contents. Through his dialogues with Simon Magus, Jung grapples with the ethical implications of harnessing the power of the unconscious for personal transformation.

Artwork and Interpretation:

The artwork of Liber Secundus becomes increasingly complex and symbolic, reflecting the deepening of Jung’s inner journey. Mandala-like structures emerge as the dominant motif, representing the Self archetype and the innate drive towards wholeness and integration. Jung’s intricate, circular designs suggest the unfolding of the psyche’s potential, the gradual actualization of the Self.

The image of the divine child, which appears in several key scenes, is another central symbol in Liber Secundus. Represented as a young boy or infant, often surrounded by concentric circles or other mandala-like forms, the divine child embodies the new, reborn self that emerges from the depths of the unconscious. This figure is closely associated with the archetype of the Self, the source of creativity, vitality, and spiritual renewal.

Other significant images include the serpent biting its own tail, known as the Ouroboros, a symbol of eternity, wholeness, and the cyclical nature of psychic life; the Philosopher’s Stone, the alchemical symbol of supreme attainment and the union of opposites; and the City of the Sun, a mystical image of the realized Self, the ultimate destination of the individuation journey.

Jung’s use of vivid colors and intricate geometric patterns in these illustrations underscores the numinous, archetypal quality of the experiences they represent. The juxtaposition of abstract forms with figurative elements creates a dreamlike, surreal atmosphere that captures the fluid, non-linear logic of the unconscious.

Psychological Concepts:

Liber Secundus develops and expands upon many of the key concepts introduced in Liber Primus, particularly the centrality of the mandala as a symbol of the Self and the process of individuation. Jung’s growing fascination with mandalas during this period reflects his belief in their universal significance as archetypal images of wholeness and integration.

The alchemical symbolism that permeates Liber Secundus prefigures Jung’s extensive study of alchemy as a metaphor for psychic transformation, a theme he would develop in great depth in works like Psychology and Alchemy and Mysterium Coniunctionis. Jung saw in the alchemists’ quest for the philosopher’s stone a powerful analog to the process of individuation, the transmutation of the base elements of the psyche into the gold of self-realization.

The encounters with anima figures like Salome and the Maiden anticipate Jung’s later formulation of the four stages of anima development: Eve (instinctual), Helen (romantic), Mary (spiritual), and Sophia (wisdom). These stages represent the progressive integration of the feminine aspect of the psyche, leading to greater emotional and intuitive depth.

The appearance of Gnostic themes and figures, such as Simon Magus and the Seven Sermons to the Dead (an intriguing text that Jung claimed to have received from the spirits of the dead), reflects Jung’s growing interest in Gnosticism as a historical parallel to his own psychological explorations. Jung saw in the Gnostics’ emphasis on personal experience, symbolic interpretation, and the pursuit of inner knowledge a kindred spirit to his own approach to the psyche.

The theme of the divine child, which recurs throughout Liber Secundus, anticipates Jung’s later writings on the archetype of the child, which he saw as a symbol of the Self’s potential for growth, renewal, and future-oriented development. The child motif also connects to Jung’s concept of the puer aeternus, the eternal youth, which he saw as a common figure in mythology and fairy tales representing the need for psychological maturation and responsibility.

Part 3: Scrutinies:

The final section of The Red Book, titled “Scrutinies,” represents Jung’s attempt to integrate and reflect upon the profound experiences recorded in the preceding pages. Here, Jung’s writing takes on a more philosophical and introspective tone as he seeks to extract the deeper meaning and implications of his visionary journey.

Allusions and Symbolism:

In the Scrutinies, Jung engages in a series of dialogues with various personified aspects of his psyche, including the Cabiri (gnome-like figures from Greek mythology associated with the mysteries of Samothrace), Ka (an Egyptian conception of the vital essence or life-force), and Philemon (who reappears in this section as a wise spiritual guide).

These dialogues are rich in mythological and philosophical allusions, drawing upon a wide range of sources from Plato and Pythagoras to Meister Eckhart and the Upanishads. Jung’s goal in these conversations is to bridge the gap between his personal experiences and the universal truths of the human condition, to find the archetypal significance behind his individual journey.

A central theme of the Scrutinies is the nature of the God-image and its relation to the Self. Jung’s reflections on this topic draw upon a variety of religious and philosophical traditions, including Christianity, Buddhism, Neoplatonism, and medieval mysticism. He grapples with the question of whether the God-image is a mere projection of the psyche or a reflection of an objective, transpersonal reality.

Ultimately, Jung comes to see the God-image as a symbol of the Self, the totality of the psyche that transcends the individual ego. This realization marks a crucial turning point in Jung’s understanding of the religious function of the psyche, which he would explore in depth in his later writings on the psychology of religion.

Artwork and Interpretation:

The artwork of the Scrutinies is sparser and more abstract than in the previous sections, reflecting the increasingly conceptual and philosophical nature of Jung’s reflections. The images are often geometric and schematic, with circular and quaternity structures predominating. These forms suggest the process of integration and wholeness that Jung saw as the ultimate goal of the individuation journey.

One of the most striking images in this section is the Systema Munditotius (“The Whole System of the World”), a complex mandala that Jung described as a “synthesis of all my most important ideas.” The image incorporates a quaternity structure, astrological symbols, and mythological figures to create a comprehensive map of the psyche and the cosmos. It reflects Jung’s growing interest in the idea of synchronicity, the meaningful coincidence of inner and outer events.

Other significant images include the Philosopher’s Stone, now depicted as a radioactive cube, suggesting the tremendous energy and potential for transformation that lies within the Self; and the Lapis Oculus (“The Stone Eye”), an all-seeing eye that represents the realized Self, the point of unity from which all the diverse elements of the psyche can be viewed and integrated.

Psychological Concepts:

The Scrutinies contain some of the most important and far-reaching ideas in The Red Book, anticipating many of the central themes of Jung’s mature psychology. Jung’s reflections on the God-image and its relation to the Self laid the groundwork for his later writings on the psychology of religion, including Answer to Job and Psychology and Religion: West and East.

In these works, Jung developed his understanding of the religious function of the psyche, arguing that the experience of the divine is a fundamental aspect of human psychology. He saw the God-image not as a literal, external reality but as a symbol of the Self, the archetype of wholeness and meaning that guides the process of individuation.

The concept of individuation, the lifelong process of psychological development and self-realization, finds its fullest expression in the Scrutinies. Jung’s dialogues with his inner figures demonstrate the ongoing nature of this process, which requires a constant balancing and integration of the conscious and unconscious elements of the psyche.

The Systema Munditotius mandala, with its synthesis of psychological, mythological, and astrological symbolism, anticipates Jung’s later development of the theory of synchronicity, the acausal connection between inner and outer events. This theory, which Jung developed in collaboration with physicist Wolfgang Pauli, suggests that the boundaries between mind and matter are not as absolute as previously thought, and that meaningful coincidences can emerge from the deeper, archetypal levels of the psyche.

Artwork Themes and Symbolism:

The artwork of The Red Book is a crucial component of the work, providing a vivid visual language that complements and enhances the written content. Jung’s illustrations are not mere decorations but are integral to the meaning and impact of the text. The images are often highly symbolic, drawing upon a rich variety of cultural, mythological, and religious sources to convey the depth and complexity of Jung’s inner experiences.

One of the most prominent and recurring symbols in the artwork is the sun disc, which appears in various forms throughout the text. The sun disc is a universal symbol of the Self, the central, organizing archetype of the psyche that represents wholeness, unity, and the integration of conscious and unconscious elements. Jung’s depiction of the sun disc often incorporates mandala-like structures, circular patterns that suggest the cyclical, transformative nature of the individuation process.

The mandala, a circular form with a central point and radiating patterns, is another key motif in The Red Book’s artwork. Jung saw the mandala as a primal image of wholeness and balance, a visual representation of the Self archetype. He believed that the spontaneous creation of mandalas in art, dreams, and visions reflected the psyche’s innate drive towards integration and self-realization.

Jung’s illustrations also incorporate a wide range of mythological and religious symbols from various traditions, reflecting his belief in the universality of certain archetypal patterns. The snake or serpent, for example, appears frequently in The Red Book, often in the form of the Ouroboros, the snake biting its own tail. This ancient symbol represents the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, as well as the union of opposites and the integration of the shadow.

Other prominent mythological figures in the artwork include the hero, often depicted slaying a dragon or other monster; the Wise Old Man, represented by characters like Philemon; and the anima, the feminine aspect of the male psyche, embodied in figures like Salome and the Maiden. These archetypal images reflect the various stages and challenges of the individuation journey, the process of psychological and spiritual development that Jung saw as the ultimate goal of human life.

To fully appreciate and understand the artwork of The Red Book, it is essential to approach it with an open, intuitive mindset, allowing the images to speak directly to the unconscious. Jung believed that the language of the psyche is primarily visual and symbolic, and that engaging with images on their own terms can bypass the rational, conceptual mind and access deeper levels of meaning and insight.

Viewers can begin by simply sitting with the images, observing their own emotional and intuitive responses without trying to analyze or interpret them right away. It can be helpful to pay attention to the colors, forms, and composition of each image, as well as any associations or memories that arise in response to them.

Jung encouraged his patients to engage in active imagination, a technique of dialoguing with inner figures and images that appear in dreams, visions, and artwork. By treating these images as autonomous entities with their own wisdom and perspective, Jung believed that individuals could gain valuable insights into their own psyche and facilitate the process of individuation.

In approaching The Red Book’s artwork, readers can experiment with this technique, imagining themselves entering into the world of the image and interacting with the figures and symbols that appear there. This process can yield surprising and meaningful insights that may not be immediately apparent from a purely intellectual analysis.

The Red Book’s Legacy and Influence:

The publication of The Red Book in 2009 was a landmark event in the history of depth psychology, providing an unprecedented glimpse into the inner world of one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. The book’s vivid imagery, profound symbolism, and penetrating insights have captured the imaginations of scholars, artists, and spiritual seekers alike, sparking a renewed interest in Jung’s life and work.

For Jungian analysts and scholars, The Red Book serves as a primary source of Jung’s ideas, offering a unique window into the germination and development of his key concepts. By tracing the evolution of Jung’s thought from the raw material of his fantasies and visions to the refined theories of his later works, The Red Book provides a invaluable resource for understanding the intellectual and creative process behind analytical psychology.

Beyond the realm of psychology, The Red Book has also had a significant impact on the fields of art, literature, and spirituality. Jung’s vibrant illustrations and calligraphy have inspired countless artists to explore the potential of visual art as a means of self-expression and psychological exploration. The book’s mythological and archetypal themes have resonated with writers and poets seeking to tap into the deeper layers of the human experience.

In the realm of spirituality, The Red Book has been hailed as a visionary work that bridges the gap between psychology and religion. Jung’s exploration of the numinous dimensions of the psyche, his engagement with a wide range of spiritual traditions, and his emphasis on the transformative power of inner experience have made him a key figure in the ongoing dialogue between Western psychology and Eastern contemplative practices.

Perhaps most importantly, The Red Book has served as an inspiration and guide for individuals seeking to embark on their own journey of self-discovery and transformation. By sharing his own intimate struggles and triumphs, Jung has provided a powerful example of the courage and integrity required to confront the depths of the psyche and emerge with newfound wisdom and self-awareness.

References:

Jung, C. G. (2009). The Red Book: Liber Novus. Ed. and Intro. by Sonu Shamdasani. Trans. by M. Kyburz, J. Peck, and S. Shamdasani. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Shamdasani, S. (2012). C. G. Jung: A Biography in Books. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Hillman, J. and Shamdasani, S. (2013). Lament of the Dead: Psychology After Jung’s Red Book. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Drob, S. (2012). Reading The Red Book: An Interpretive Guide to C.G. Jung’s Liber Novus. New Orleans: Spring Journal Books.

Stein, M. and Arzt, T. (Eds.) (2016). Jung’s Red Book for Our Time: Searching for Soul Under Postmodern Conditions. Asheville, NC: Chiron Publications.

Domenici, G. (2018). Jung’s Nietzsche: Zarathustra, The Red Book, and “Visionary” Works. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hoeller, S. A. (2019). The Gnosis of C.G. Jung: Gnostic Traditions in The Red Book. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books.

Owens, L. (2011). Jung in Love: The Mysterium in Liber Novus. Salt Lake City: Gnosis Archive Books.

Kingsley, P. (2018). Catafalque: Carl Jung and the End of Humanity. London: Catafalque Press.

Corbett, L. (2011). The Red Book Dialogues. Asheville, NC: Chiron Publications.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Influences on Jung

0 Comments