An In-Depth Exploration of the Orphic Cult Object Theory

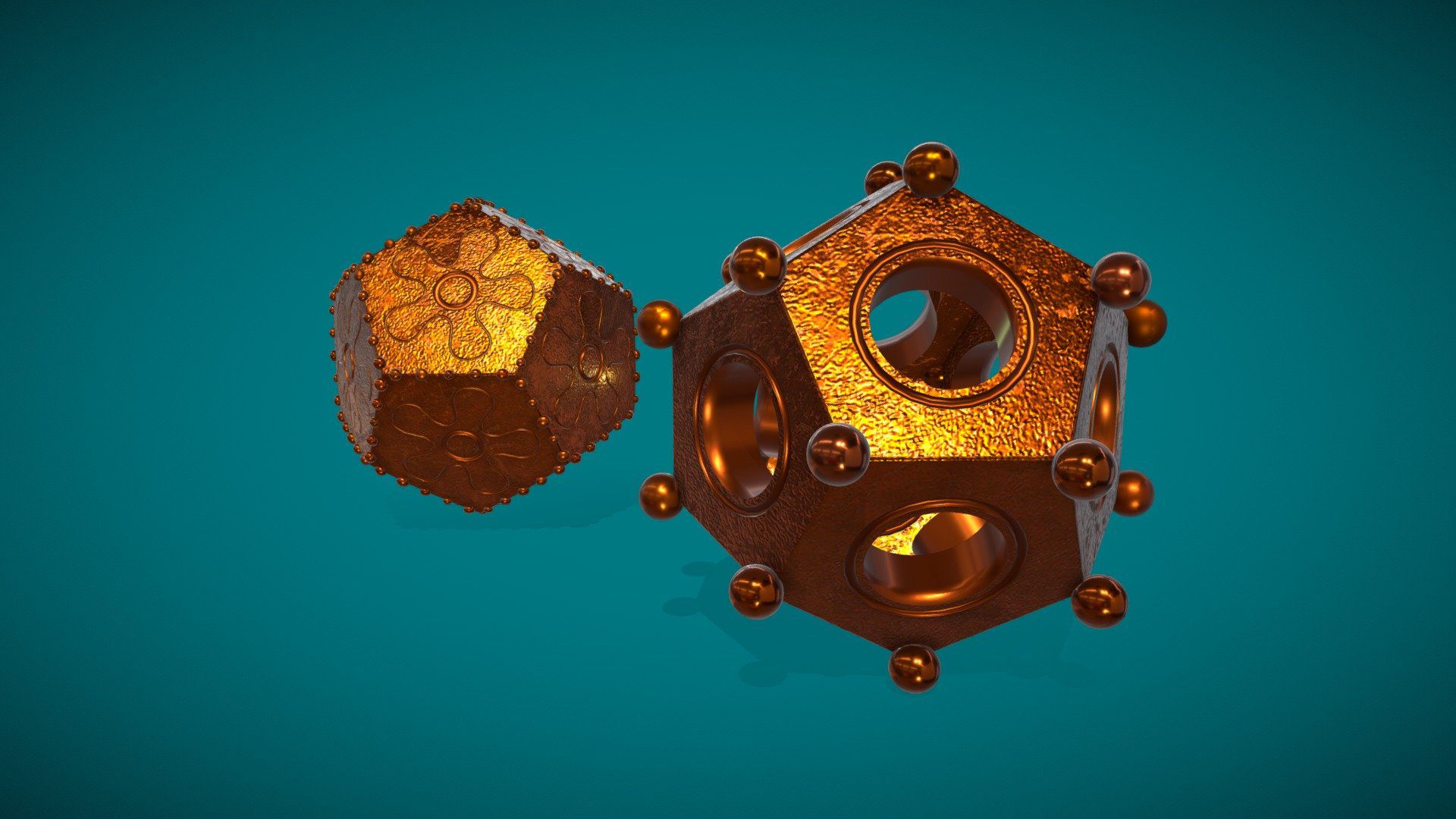

Among the most enigmatic artifacts from the ancient world are the so-called Roman dodecahedra – small, hollow, twelve-faced polyhedrons made of bronze or stone, each face featuring a circular hole of varying diameter. Approximately 100 such objects, dated primarily to the 2nd-4th centuries CE, have been unearthed across the expanse of the former Roman Empire, with particular concentrations in the western provinces of Gaul and Britain. Despite extensive scholarly scrutiny, the original function and significance of these peculiar dodecahedra remain shrouded in uncertainty, with hypotheses ranging from surveying instruments to candleholders to military banner ornaments.

One of the most intriguing and tantalizing interpretations posits that the dodecahedra served as ritual implements in the Orphic Mysteries – a Greco-Roman spiritual tradition centered on the mythical figure of Orpheus that offered initiates a path to personal salvation and union with the divine. This article aims to thoroughly examine the evidence, reasoning, and implications behind this “Orphic cult object” theory, evaluating its plausibility and potential to shed light on these enduring archaeological enigmas.

The Orphic Mysteries: Key Beliefs, Practices, and Symbols

To properly assess the proposed link between the dodecahedra and Orphism, a solid grasp of the cult’s core tenets, rituals, and symbolic language is essential. The Orphic Mysteries emerged in ancient Greece, likely as early as the 6th century BCE, as a reformist movement within the broader religious landscape. Inspired by the mythical poet and prophet Orpheus, famed for his ability to charm all of nature with his lyre and his descent into the underworld to retrieve his deceased wife Eurydice, the Orphics articulated a worldview and salvific path distinctly at odds with the mainstream Olympian religion.

Central to Orphic doctrine was the concept of metempsychosis or transmigration of souls – the belief that the human soul is divine and immortal, but finds itself trapped in a cycle of reincarnation through successive mortal bodies. This predicament was explained through the Orphic myth of Dionysus Zagreus, the infant god who was torn apart and consumed by the Titans, from whose ashes humanity arose, bearing a dual nature – a divine Dionysian spark imprisoned in a Titanic bodily tomb. The ultimate aim of Orphic practice was to purify and liberate this inner divine element, breaking free of the cycle of rebirth to attain eternal blessedness in the afterlife.

To this end, the Orphics prescribed a way of life centered on ritual purity, asceticism, and secret initiatory rites. Adherents abstained from meat and certain other foods, wore white linen garments, and cultivated a close relationship with the gods and spirits of the dead through offerings, prayers, and rites of purification. The most devoted Orphics were initiated through private mystery rites – ceremonies shrouded in secrecy that likely involved dramatic reenactments of sacred myths, esoteric teachings, and transformative experiences intended to prefigure the soul’s journey after death.

Orphic symbolism drew heavily on mythic motifs and natural imagery believed to encode profound cosmic truths. The lyre of Orpheus represented the harmony of the universe and the soul’s attunement to the divine. The egg featured prominently as a symbol of the Orphic cosmos, the primordial unity from which all multiplicity and duality emerged. The mirror served as an emblem of self-knowledge and revelation, while the pinecone was revered as an image of the secret “heart” of the mysteries.

Rituals employed an array of sacred implements and substances. Gold tablets inscribed with hexametric verses, often buried with the deceased, provided initiates with guidance and passwords for navigating the perils of the underworld. The “Orphic Hymns,” a collection of 87 devotional poems, were recited to invoke the various deities. Rites involved ceremonial processions, chanting, music, dancing, and the use of sacred objects like ritual mirrors, winnowing fans, pinecones, and serpent-entwined staffs or thyrsoi.

This rich tapestry of myth, symbol, and rite formed the context in which an Orphic interpretation of the Roman dodecahedra could be situated. By decoding the potential Orphic significance of the dodecahedron form and investigating its ritual functionality, researchers aimed to unveil a lost dimension of ancient spiritual practice.

The Dodecahedron in Pythagorean and Platonic Thought: Foundations for an Orphic Interpretation

The form of the regular dodecahedron – a three-dimensional solid composed of twelve pentagonal faces – held profound symbolic and cosmological significance in the ancient world, particularly within the Pythagorean and Platonic philosophical traditions, which deeply influenced and intersected with Orphic thought.

The Pythagoreans, a philosophical and religious community founded by Pythagoras in the 6th century BCE, venerated the dodecahedron as a sacred geometric form embodying fundamental cosmic principles. They associated it with the element of aether or quintessence, the divine substance comprising the heavenly bodies and the realm of the gods, distinct from the four terrestrial elements of earth, water, air, and fire. The twelve pentagonal faces were linked to the zodiac, the bands of constellations through which the sun, moon, and planets appeared to travel. As a harmonious synthesis of spherical perfection and the pentagon’s golden ratio proportions, the dodecahedron symbolized the unity and divine order underlying the cosmos’s apparent multiplicity and chaos.

These ideas found their most sophisticated expression in the cosmological vision of Plato, whose metaphysics and cosmology were profoundly shaped by Pythagorean and Orphic doctrines. In the Timaeus, Plato’s grand mythic account of the universe’s creation, the divine craftsman or Demiurge constructs the World Soul and the cosmos using a series of geometric patterns, culminating in the form of the dodecahedron. The dodecahedron is identified as the shape “used for the whole universe,” encompassing the other four elements and their associated regular solids within its twelve pentagonal faces. It is the all-embracing framework of the cosmos, the scaffolding of the zodiac, and the pattern of divine perfection that gives form and order to the material world.

For Plato, as for the Orphics, the aim of human life was to achieve likeness to god – to realign the soul with the harmonious order and eternal truth represented by the World Soul and the dodecahedron. This was to be accomplished through a combination of philosophical contemplation, moral discipline, and ritual initiation – practices that aimed to purify the soul of its material attachments and awaken its innate knowledge of the Forms. The dodecahedron thus served as a potent symbol and conceptual model for the Orphic and Platonic path of salvation – a visual emblem of the soul’s true home and destination.

While Plato never explicitly links the dodecahedron to Orphic practice, later Neoplatonic thinkers, such as Syrianus and Proclus, more directly associate it with the Orphic mysteries. Proclus, in his Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus, describes the dodecahedron as “the Orphic figure par excellence,” a sacred symbol of the all-encompassing “Aeon” or cosmic god Phanes, who united all opposites and contained the entire universe within himself. For the Neoplatonists, the dodecahedron was the geometric key to the Orphic esoteric doctrine of the soul’s divine origin and destiny.

This rich symbolic and cosmological heritage provided a fertile ground for interpreting the Roman dodecahedra as concrete instances of a sacred Orphic form – small-scale material conduits for aligning the initiate’s soul with the grand cosmic dodecahedron and the saving truth it embodied. By investigating the specific material, structural, and contextual features of these enigmatic artifacts, researchers sought to extend and ground this largely textual tradition of metaphysical speculation in ritual practice.

The Roman Dodecahedra: Material, Structural, and Contextual Features

The Roman dodecahedra exhibit a remarkable consistency in their basic form and construction, despite variations in size, material, and minor structural details. Most are small enough to fit comfortably in the palm of the hand, with diameters typically ranging from 4 to 11 centimeters. While the majority are made of copper alloys such as bronze or brass, a few are carved from stone, including examples in serpentine, granite, and marble.

All feature twelve regular pentagonal faces, each bearing a circular hole in the center. The diameter and shape of these holes vary considerably across different examples, with some being perfectly round and others more elliptical or irregular. The holes within a single dodecahedron often differ in size, seemingly arranged in opposing pairs. Many display small knobs or rounded protrusions at the vertices where the pentagonal faces meet, though whether these were functional or merely ornamental remains uncertain.

The precision and regularity of the pentagonal faces suggest the dodecahedra were fabricated using molds or templates, likely by skilled artisans familiar with geometric forms. However, the variations in size, material, and hole configuration indicate they were not mass-produced according to a single standardized pattern but could be customized to suit individual needs and preferences.

Contextually, the dodecahedra have been recovered from a diverse range of sites across the western Roman Empire, with notable concentrations in Gaul and Britain. They have been found in military camps, villas, urban domestic contexts, and graves, often in association with other small metal objects like coins, jewelry, and toiletry items. The wide geographic and contextual distribution suggests they served a function that cut across regional, social, and economic boundaries.

Dating the dodecahedra has proven challenging due to the lack of inscriptions or other clear temporal markers, but most examples are broadly assigned to the 2nd-4th centuries CE based on associated finds and site chronologies. This places them in a period when the Orphic and other mystery cults were widely disseminated across the Empire, offering personal salvation and spiritual meaning to individuals from all walks of life.

While the material and structural features of the dodecahedra are well-documented, their precise function remains elusive. No surviving ancient text unambiguously mentions or describes these objects, leaving researchers to infer their purpose from a combination of educated guesswork, analogical reasoning, and contextual evidence. This gap in the historical record has given rise to numerous interpretations, including the theory that they served as Orphic ritual implements.

Ritual Use Hypothesis 1: Divinatory Devices

One of the most compelling and widely discussed hypotheses for the dodecahedra’s ritual use is that they functioned as divinatory devices or sortition machines for generating random outcomes in a ritualized setting. This interpretation draws on several key features of the artifacts:

- The varied size and arrangement of the holes, which could yield different probabilities and combinations when the dodecahedron was rolled or rotated.

- The knobs at the vertices, which may have prevented the object from rolling too freely and ensured a stable resting point.

- The portability and tactile nature of the dodecahedra, which would allow them to be easily handled and manipulated in a ritual context.

Divination and sortition – the practice of seeking guidance or answers from the gods through the random generation of signs or symbols – was a common feature of ancient Greek and Roman religion, including the Orphic mysteries. Orphic ritual texts and mythic narratives often describe the drawing of lots or the casting of objects to determine an initiate’s fate or spiritual status. The gold tablets buried with Orphic devotees, for instance, sometimes bear enigmatic letter sequences or symbols that may have been used as divinatory ciphers.

In this context, the Roman dodecahedra could have served as highly sophisticated and symbolically resonant tools for divination. By associating each face or hole with a particular deity, zodiac sign, or metaphysical principle, the fall of the dodecahedron could be read as a message from the gods revealing the initiate’s progress on the path to salvation. The twelve faces might represent the twelve houses of the zodiac, with the varying hole sizes corresponding to the relative influence or auspiciousness of each house. Alternatively, the faces could symbolize different stages or challenges in the soul’s cosmic journey, with the outcome of the roll indicating the initiate’s readiness to proceed.

The use of a dodecahedron – a microcosmic image of the universal Aeon – as a divinatory instrument would be highly fitting within Orphic theology. By aligning one’s fate with the pattern of the cosmos through the fall of the sacred polyhedron, the initiate would actively participate in the great drama of cosmic destiny that the dodecahedron embodied. The act of casting or rolling the dodecahedron could be seen as a ritual recapitulation of the soul’s descent into matter and its ultimate return to divine unity – a physical enactment of the Orphic cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

While the divinatory hypothesis offers a compelling and symbolically rich interpretation of the dodecahedra, it is not without its challenges. The lack of explicit textual evidence for this specific use leaves room for alternative explanations. The irregular and variable size of the holes may reflect a more practical or ornamental function rather than a probabilistic one. The small size of some examples may have made them difficult to handle as dice or casting objects. Nevertheless, the alignment between the dodecahedron’s cosmological symbolism and the Orphic preoccupation with fate and salvation makes this hypothesis a powerful and plausible contender.

Ritual Use Hypothesis 2: Contemplative and Initiatory Focuses

Another compelling hypothesis for the Roman dodecahedra’s ritual function is that they served as contemplative and initiatory focuses – portable sacred objects used to stimulate mystical visions, facilitate meditation on cosmic truths, and induce altered states of consciousness in the context of Orphic initiation rites.

This interpretation draws on the dodecahedron’s rich Pythagorean and Platonic symbolism as an image of the divine cosmic order, as well as on analogies with other ancient and modern traditions that employ polyhedra or geometrically complex objects as spiritual tools. In many cultural contexts, focusing one’s gaze or attention on a sacred geometrical pattern is believed to align the mind with a higher reality, opening channels of communication with the divine realm.

The intricate interplay of regular pentagons, circles, and knob-like vertices on the surface of the Roman dodecahedra would provide a potent visual stimulus for such contemplative practice. By gazing into the holes or tracing the edges and contours of the polyhedron, the initiate could enter a state of focused attention or trance, attuning their consciousness to the harmonies of the cosmos. The dodecahedron would function as a kind of spiritual lens or portal, directing the mind beyond the realm of appearances to the eternal truths that lay behind.

This use would be particularly resonant in the context of Orphic initiation, which aimed to awaken the initiate to their divine nature and destiny through a process of ritual death and rebirth. By meditating on the dodecahedron as a symbol of the Orphic cosmic egg or the divine unity of Phanes, the initiate would be reminded of their true home and identity, shedding the illusions of mortal existence. The experience of gazing into the dodecahedron’s depths could induce visions of the soul’s journey through the celestial spheres, previewing the ultimate revelation of the mysteries.

The portability and tactile nature of the dodecahedra would also support their use as personal devotional objects, carried by initiates as constant reminders of their spiritual path. The variations in size and decoration could reflect different levels of initiation or spiritual attainment, with more complex and finely crafted examples reserved for higher grades. The presence of dodecahedra in both domestic and funerary contexts suggests they may have served as protective talismans or guides for the soul in the afterlife.

However, as with the divinatory hypothesis, the lack of explicit textual evidence for this specific use of the dodecahedra leaves room for doubt. The small size and dense configuration of the holes on some examples may not have been conducive to prolonged contemplation. The variations in form and context may point to a more diverse range of functions than a single ritual purpose. Nevertheless, the symbolic resonance of the dodecahedron with Orphic and Platonic ideas of cosmic unity and the soul’s transformation makes this hypothesis a viable and intriguing possibility.

Objections, Limitations, and Alternative Theories

Despite the compelling symbolic and contextual evidence for an Orphic ritual interpretation of the Roman dodecahedra, there remain significant challenges and limitations to this theory that must be acknowledged:

- Lack of direct textual evidence: Perhaps the most significant obstacle to the Orphic hypothesis is the absence of any explicit reference to dodecahedral objects in surviving Orphic or ancient Greek and Roman texts. While the dodecahedron is discussed as a cosmological symbol in Platonic and Pythagorean philosophy, there are no unambiguous descriptions of its use in ritual contexts or initiatory practices. This lacuna in the textual record leaves considerable room for doubt and alternative explanations.

- Contextual diversity: The wide range of contexts in which the dodecahedra have been found – including military sites, domestic spaces, and graves – suggests they may have served multiple functions or held different meanings for different individuals and communities. While an Orphic ritual use is plausible in some cases, it is unlikely to account for all known examples. The variations in size, material, and specific features may reflect a diversity of purposes and symbolic associations.

- Geographic and chronological distribution: The concentration of dodecahedra finds in the western provinces of the Roman Empire, particularly Gaul and Britain, does not neatly align with the known distribution of Orphic communities and practices, which were more prevalent in the Greek-speaking eastern Mediterranean. Additionally, the apparent peak in dodecahedra production during the 2nd-4th centuries CE may not correspond to the heyday of Orphic activity, which is often traced to earlier periods. These discrepancies suggest that the dodecahedra may have been more closely associated with local religious traditions or syncretistic practices in the Roman provinces.

- Lack of comparative examples: While the dodecahedron held profound symbolic significance in ancient Greek thought, there are no clear parallels for its use as a ritual implement in other ancient Mediterranean religions or mystery cults. The scarcity of comparable artifacts or practices makes it more challenging to situate the Roman dodecahedra within a broader context of esoteric religious praxis.

Given these limitations, alternative theories for the function and meaning of the Roman dodecahedra must also be considered. Some researchers have proposed more mundane uses, such as surveying instruments, candleholders, or military banner ornaments. Others have suggested they may have served as gaming pieces, children’s toys, or decorative objects. While these interpretations may not fully account for the dodecahedra’s intricate symbolism and wide distribution, they remain viable possibilities that cannot be definitively ruled out.

Ultimately, the enigma of the Roman dodecahedra is unlikely to be fully resolved without further archaeological discoveries or textual evidence. The Orphic ritual hypothesis, while compelling and symbolically resonant, must be weighed against the limitations of the available data and the plausibility of alternative explanations. As with many aspects of ancient esoteric traditions, a degree of uncertainty and ambiguity may be unavoidable.

Bibliography

- Alvar, J. (2008). Romanising oriental gods: Myth, salvation and ethics in the cults of Cybele, Isis and Mithras. Leiden: Brill.

- Bremmer, J. N. (2014). Initiation into the mysteries of the ancient world. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Burchett, C. (2009). “The Roman Dodecahedra: A Survey and Some Thoughts on Their Use.” The Celator, 23(4), 6-13.

- Edmonds, R. G. (2013). Redefining ancient Orphism: A study in Greek religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eisenberg, J. M. (2008). “The Orphic Mysteries: Plato’s ‘Symposium’ and the Ancient Mysteries of Dionysus.” Parabola, 33(3), 56-63.

- Guthrie, W. K. (1993). Orpheus and Greek religion: A study of the orphic movement. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Harrison, J. E. (1922). Prolegomena to the study of Greek religion. Cambridge: University Press.

- Herrero, . B. M. (2010). Orphism and Christianity in late antiquity. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kern, O., & Dieterich, A. (1911). Die griechischen Mysterien der klassischen Zeit. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung.

- Kingsley, P. (1995). Ancient philosophy, mystery, and magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Martínek, B., & Mařík, R. (2012). “The Roman Dodecahedron as an Astronomical Instrument.” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 12(1), 211-219.

- Nagy, G. (1994). “The Dodecahedron in the Timaeus: Plato’s Cosmic Model and the Myth of Er.” In J. J. Cleary & W. Wians (Eds.), Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy (Vol. 9, pp. 143-170). Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- Painter, E. F. (1980). “The Roman Dodecahedron: A New Perspective.” Expedition, 22(4), 39-46.

- Pérez Jiménez, A. (2002). “Orphic Ideas in Plato’s Myth of Er.” Itaca: Quaderns Catalans de Cultura Clàssica, 18, 117-128.

- Riedweg, C. (2005). Pythagoras: His life, teaching, and influence. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Sjöö, M. (1999). The great cosmic mother: Rediscovering the religion of the earth. New York, NY: HarperOne.

- Smith, A. (1991). “The Orphic Myth of Dionysus and the Mysteries: Sacrifice, Death and Renewal.” Pomegranate, 1(1), 8-26.

- Struck, P. T. (2004). Birth of the symbol: Ancient readers at the limits of their texts. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Tortorelli Ghidini, M. (1975). “Un mito orfico in Plotino (Enn. IV 3,12).” La Parola del Passato, 30, 356-360.

- Ulansey, D. (1989). The origins of the Mithraic mysteries: Cosmology and salvation in the ancient world. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Versnel, H. S. (1993). Inconsistencies in Greek and Roman religion II: Transition and reversal in myth and ritual. Leiden: Brill.

- Waterfield, R. A. H. (2011). The Theology of Arithmetic: On the mystical, mathematical and cosmological symbolism of the first ten numbers. Grand Rapids, Mich: Phanes Press.

- Weiss, C. (1990). “Paradox and Aporia in Plato’s Notion of the Ineffable.” Epoché: A Journal for the History of Philosophy, 3, 3-22.

- West, M. L. (1983). The Orphic poems. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

0 Comments