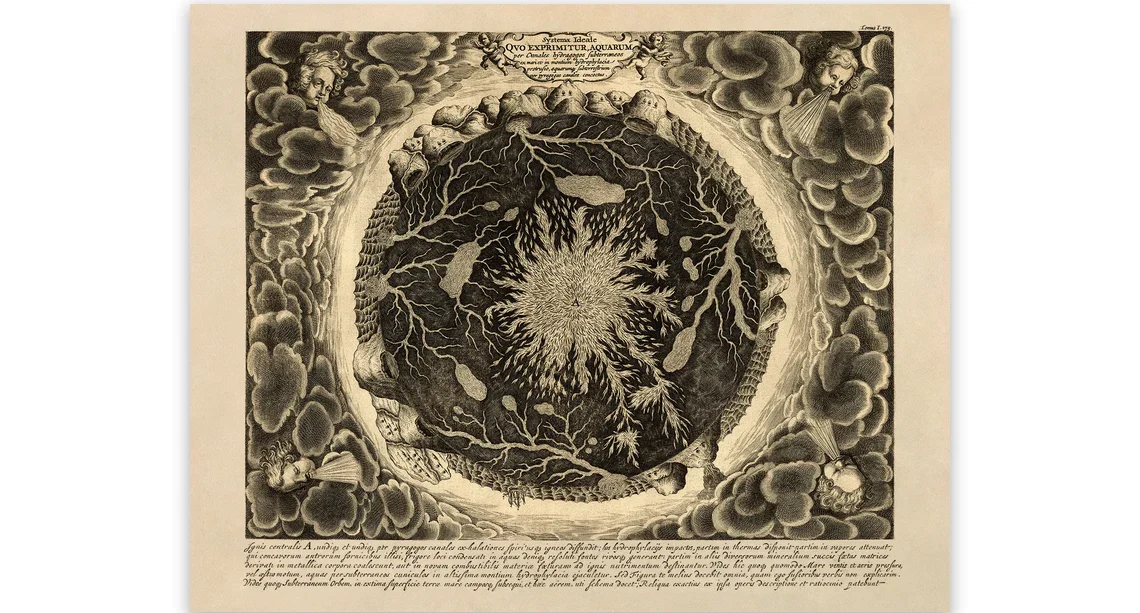

Emotion: A Conjunction of Inner and Outer Spheres

James Hillman’s book Emotion: A Comprehensive Phenomenology of Theories and Models presents a philosophical and psychological exploration of emotions, investigating them not as mere physiological responses but as integral aspects of human experience and soul life (Hillman, 1960). Hillman critiques the way traditional psychology and psychiatry have often treated emotions in mechanistic, reductive ways, urging instead a deeper understanding of emotions as vital expressions of the psyche (Hillman, 1960).

Hillman’s Critique of Theories of Emotion

Hillman discusses the psychoanalytic tradition, particularly focusing on the work of Freud and his followers (Freud, 1915). In Freud’s view, emotions were often seen as tied to unconscious drives and repressed desires (Freud, 1915). Hillman critiques this model for reducing emotional life to mechanistic causes and urges that emotions should not be seen as mere outcomes of repressed content, but as more complex expressions of soul and inner life. He moves beyond Freud’s mechanistic view to consider how emotions serve a deeper, more meaningful purpose in the psyche’s development.

Cognitive theories, particularly those associated with figures like Paul Ekman and Richard Lazarus, emphasize the role of thinking, appraisals, and evaluations in shaping emotional responses (Ekman, 1992; Lazarus, 1991). Hillman critiques this focus on cognition, arguing that it treats emotions as secondary to thought and as things that can be simply “controlled” or “regulated” (Hillman, 1960). Hillman takes issue with the idea that emotions are essentially cognitive evaluations, suggesting instead that emotions are primary, rich experiences that should be understood in their own right, not merely as reactions to thoughts.

Hillman also engages with theories that focus on the physiological aspects of emotion, such as those proposed by William James (James, 1884). According to James, emotions arise from bodily reactions to stimuli (e.g., we feel afraid because our body reacts with increased heart rate, sweating, etc.) (James, 1884). Hillman critiques this reductionist approach, arguing that emotions should not be seen merely as bodily states. Instead, they should be understood as reflections of the soul’s deeper needs and longings (Hillman, 1960).

Drawing from his own work in archetypal psychology, Hillman suggests that emotions should be viewed through the lens of archetypes—universal patterns of human experience that shape how we experience and understand emotions . Emotions are not just individual or subjective phenomena but are also expressions of larger, collective, and mythic forces (Hillman, 1960). For Hillman, archetypal figures like the Warrior, the Lover, and the Sage embody different aspects of emotional experience, offering insights into the various ways emotions manifest in our lives (Hillman, 1960).

Existential and Phenomenological Approaches to Emotion

In this vein, Hillman emphasizes the existential and phenomenological approaches to emotion, especially the idea that emotions are fundamental to our experience of being-in-the-world (Heidegger, 1927; Merleau-Ponty, 1945). Influenced by philosophers like Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty, Hillman suggests that emotions are not simply responses to external events or internal states but are part of the very fabric of existence (Hillman, 1960). They reveal something essential about our relationship to the world, to others, and to ourselves (Hillman, 1960).

One of Hillman’s most original contributions in Emotion is his treatment of emotions as expressions of the soul. In Hillman’s view, emotions are not simply reactions to stimuli or unconscious drives but are meaningful and profound ways through which the soul communicates with us. Instead of attempting to eliminate or control emotions, Hillman advocates for understanding them and seeing them as rich, transformative processes that guide us toward self-knowledge and a deeper connection with life’s mysteries (Hillman, 1960).

Hillman critiques modern psychology, psychiatry, and the medical model for their tendency to pathologize and over-medicalize emotional experiences. He is particularly critical of the reduction of emotional suffering to mere biochemical imbalances or neurological dysfunctions, arguing that this approach misses the depth and richness of emotional life. In contrast, Hillman calls for an approach that respects the complexity of emotions and their role in human development (Hillman, 1960).

Hillman’s overarching philosophical position is that emotions should not be seen as mere phenomena to be studied or “treated” but as vital aspects of the soul that deserve attention, exploration, and integration. For him, emotions are not to be reduced to mechanistic causes but are powerful, often poetic expressions that can help us understand our deeper selves . By recognizing the rich, archetypal, and existential dimensions of emotions, Hillman offers a vision of emotional life that is far more expansive than traditional psychological models typically offer (Hillman, 1960).

The Dual Nature of Emotion

Emotion is fundamentally a description in our brain stem of our relationship between the inner self and the outer world (LeDoux, 1996). It reflects how our body and mind respond to changes in the environment, influenced by the deep neural processes that shape how we perceive ourselves and the world around us (LeDoux, 1996). The emotional experience is layered: part of it is learned and stored in our brain like data on a hard drive, holding past emotional responses and beliefs, while another part is constantly updated to reflect the ongoing changes in this relationship, similar to the dynamic functions of RAM in a computer (LeDoux, 1996). This dual system makes emotion complex, as it operates on both a subconscious, automatic level and a conscious, reflective level, integrating a variety of brain networks that are not always in alignment (LeDoux, 1996).

Emotion arises from a deep, often unconscious system within the brain that processes this inner-outer relationship in real-time (LeDoux, 1996). It represents the body’s instinctive reaction to perceived threats or rewards, preparing the self to act, even before the thought of a situation has fully formed in the conscious mind (LeDoux, 1996). This is why emotions can often be irrational or overwhelming—they are a direct, rapid response to a changing environment that bypasses reason (LeDoux, 1996). Some of this emotional content, however, is learned through experience and becomes stored in our subcortical brains as patterns of emotional reactions or beliefs about ourselves and the world (LeDoux, 1996). These emotional patterns, much like files on a computer, can be accessed and triggered by similar circumstances, bringing forward past responses (LeDoux, 1996).

This division between learned emotional patterns and real-time emotional processing contributes to the ambivalence we feel toward emotion both personally and culturally (Damasio, 1994). Emotion can feel overwhelming or illogical, yet it is essential for survival (Damasio, 1994). We often struggle with how to understand and react to our own emotions or the emotions of others (Damasio, 1994). In therapy, for example, there is ongoing debate about the importance of validating emotions versus addressing them (Greenberg, 2002). Some schools of therapy emphasize the need to delve into and understand emotional experiences, while others argue that emotions should be kept in check to prevent them from taking over (Greenberg, 2002). This tension is rooted in the fact that emotion, as a process, is both a learned response and an ever-evolving part of our constant negotiation with the environment (Damasio, 1994).

Emotion in Political and Cultural Debates

Culturally, the complexity of emotion plays out in political debates, too, where people argue over who is “acting emotionally” or “irrationally” (Nussbaum, 2001). These debates often obscure the fact that everyone is subject to emotion, and the disagreements tend to center on which group is the rightful victim or deserves the most sympathy—the business owner, for example, or the disenfranchised poor (Nussbaum, 2001). These arguments are built on the same emotional processes that underpin all of our experiences, yet we often fail to recognize the shared nature of emotional responses across different groups and perspectives (Nussbaum, 2001). Emotion thus reflects an internal and external struggle, one that is deeply personal and yet universally human (Nussbaum, 2001).

Understanding emotion’s dual nature—its stored and automatic elements and its constant updates in response to the present moment—offers insights into the complexity of emotional life (LeDoux, 1996). It highlights the tension between the learned past and the unpredictable future, both of which influence how we react emotionally, often without our conscious awareness (LeDoux, 1996). This is why, in therapy and in life, our emotional responses can feel so layered, contradictory, and sometimes out of our control, yet they are a necessary part of our ongoing relationship with ourselves and the world around us (Greenberg, 2002).

Emotion serves as a bridge between our inner and outer worlds, allowing us to experience life in a non-empirical, subjective way (Damasio, 1994). It complements our objective understanding of the world, but does so in a way that is pre-conscious and deeply interwoven with the ways our body budgets and allocates energy (Damasio, 1994). In essence, emotion is not just about what we feel in the moment; it is also our brain’s way of seeing into the future—predicting it based on patterns it has inferred from the past (Damasio, 1994).

The Fingerprint of the Self

The parts of emotion encoded in our brainstem are a direct imprint of how the world has shaped us, how we relate to it, and how we understand ourselves in relation to others (Damasio, 1994). These emotional imprints form a kind of “fingerprint,” a unique expression of how we’ve been affected by everything around us—from our genes, to our parents, our friendships, our cultures, and even the media we consume (Damasio, 1994). It is how we make sense of both the self and the world, in ways that are far more essential and deeply rooted than what we can articulate through language (Damasio, 1994).

James Hillman’s perspective on this is crucial; he suggests that these deep emotional expressions are the true reflections of the soul (Hillman, 1960). They are not simply reactions or byproducts of our conscious thoughts—they are integral to who we are (Hillman, 1960). This is why a purely empirical approach, grounded in cognitive-behavioral psychology, will always fall short in reflecting the totality of human psychology (Hillman, 1960). Emotion is not simply an adjunct to our cognition; it is how we touch the world, and how the world touches us back (Hillman, 1960). The inner and outer realms—the subjective and the objective—are intertwined through emotion, which helps us synthesize and navigate both (Hillman, 1960).

When our inner conceptualization of the world becomes misaligned with reality, we experience rupture (Hillman, 1960). This misalignment manifests as projections, misperceptions, and maladaptive relationship dynamics, where our expectations no longer reflect the true nature of the world or the people around us (Hillman, 1960). A great deal of psychotherapy focuses on helping us resynchronize this mismatch (Yalom, 1980). Whether through IFS, psychodynamic work, or gestalt therapy, the aim is to help us reconnect our inner world with the outer world so that our perceptions of ourselves, others, and reality align more accurately (Yalom, 1980).

This process of alignment, or misalignment, is something that has also been deeply explored by philosophers throughout history (Solomon, 1993). In many ways, Emotion, in its deepest form, serves as a bridge between the inner and outer worlds, offering us a non-empirical, subjective understanding of reality in addition to our objective knowledge . It operates largely at a pre-conscious level, intertwined with how our body “budgets” energy and anticipates the future, constantly refining its predictions based on past patterns . Emotion is not simply a passive reaction; it is a dynamic, ongoing process that helps us navigate the world by drawing on both our learned experiences and biological imperatives . The emotional systems encoded in the brainstem are like fingerprints, deeply imprinted with the lessons of the world and our own internal states. These emotional responses reflect our individual histories and, more broadly, the influences of our genes, our parents, friends, cultures, and even the media we consume (Damasio, 1994). Through emotion, we come to understand ourselves and the world in ways that transcend intellectual or verbal knowledge—ways that are often more profound and far-reaching.

James Hillman, in his work, emphasizes that these emotions, these deep-seated expressions, are not just psychological reactions but are indeed the true reflections of the soul (Hillman, 1960). They go beyond what we can think or articulate with language, offering insight into the lived experiences and internal realities that shape us . This is why a purely cognitive-behavioral approach to psychology, which focuses only on observable behavior and rational thought, can never fully capture the depth of our psychological experience . Emotion is the way we touch the world, and it is the way the world touches us. It is the conduit through which our subjective internal world and the objective external world meet . When these two worlds are misaligned—when our inner conceptualization of reality becomes disconnected from the outer reality—this leads to ruptures, projections of inaccurate systems, and distorted relational dynamics . These mismatches fuel much of the conflict we see in our personal lives, as well as in our collective cultural and political discourses .

Psychotherapeutic Approaches to Aligning Inner and Outer Worlds

Much of the disagreement in psychotherapy revolves around how best to address this dissonance. The various schools of thought in therapy are all, in some form, attempting to resynchronize the inner and outer worlds so that they align more accurately, allowing the individual to experience a more authentic and coherent sense of self (Yalom, 1980). Whether through Carl Jung’s concepts of the anima, animus, and shadow, Freud’s exploration of the id and ego, Adlerian compensation, or the object relations model, therapists seek to help clients understand how their inner worlds have been shaped by both internal and external forces . These differing models reflect the different ways that therapists attempt to reconcile the mismatch between inner and outer worlds and promote psychological harmony.

This reconciliation of the inner and outer worlds is not just a therapeutic endeavor; it is also a philosophical one. Philosophers have long grappled with the tension between these two realms, seeking to understand the relationship between our subjective experiences and the objective world. For example, Heidegger’s exploration of Being highlights the disconnection between our experience of existence and the world around us, calling for a deeper alignment between self and world (Heidegger, 1927). Nietzsche’s notion of the “will to power” offers a similar idea, pointing to the necessity of overcoming the fragmentation between our internal drives and the external challenges that shape us (Nietzsche, 1887). Plato’s tripartite soul, with its rational, spirited, and appetitive elements, illustrates the necessity of harmony between different facets of the self in order to live a virtuous life (Plato, trans. 1997), while Aristotle’s theory of emotions underscores the importance of balance between reason and emotion in achieving eudaimonia, or human flourishing (Aristotle, trans. 2009).

Moreover, many religious traditions can be seen as cosmologies designed to describe and restore balance between these two spheres—the inner and the outer, the subjective and the objective . Religion often offers a framework for understanding where emotion fits in the broader scheme of life, asking whether emotion is inherently good or bad, and where it should be allowed to flow freely or restrained. Different religious teachings provide guidance on how to align one’s internal world with a divine or cosmic order. The moral structures of these traditions often act as mirrors to our emotional experience, guiding us toward a state of balance and alignment (Armstrong, 1993).

The Transformative Potential of Understanding Emotion

If we could learn to truly see the role of emotion in shaping our understanding of the world, this recognition could transform our culture. Once we see how emotion plays a central role in mediating the relationship between the inner and outer worlds, we cannot unsee it. We will begin to notice the ways in which our emotional lives shape the very narratives we live by—shaping not just individual lives, but the larger cultural narratives that we collectively embrace. This realization holds the potential to shift how we relate to each other, to ourselves, and to the world at large, offering a more integrated and holistic way of understanding the self and our place within the larger fabric of existence (Goleman, 1995).

Bibliography

- Aristotle. (2009). The Nicomachean Ethics (D. Ross, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

- Armstrong, K. (1993). A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Ballantine Books.

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

- Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6(3-4), 169-200.

- Freud, S. (1915). The unconscious. SE, 14: 159-204.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books.

- Greenberg, L. S. (2002). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings. American Psychological Association.

- Heidegger, M. (1927). Being and Time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Harper & Row.

- Hillman, J. (1960). Emotion: A Comprehensive Phenomenology of Theories and Their Meanings for Therapy. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- James, W. (1884). What is an emotion? Mind, 9(34), 188-205.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford University Press.

- LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. Simon & Schuster.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phenomenology of Perception (C. Smith, Trans.). Routledge.

- Nietzsche, F. (1887). On the Genealogy of Morals (W. Kaufmann & R. J. Hollingdale, Trans.). Random House.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge University Press.

- Plato. (1997). Complete Works (J. M. Cooper, Ed.). Hackett Publishing Company.

- Solomon, R. C. (1993). The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life. Hackett Publishing Company.

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books.

0 Comments