Our phobias are often metaphors for our most unconscious parts of self. In the 2013 movie Gravity, Sandra Bullock plays an astronaut marooned in space. At every moment she is seconds from spinning into the hopeless oblivion of deep space. Bullock’s character must use her ingenuity to navigate the shuttles and space stations to find her way back to earth. During her time in space Bullock is haunted by trauma from her past. Numerous shots suggest that her time in space causes her to regress to infancy and face not only trauma but primal childhood fear.

It’s fairly common for patients with insecure or reactive attachment to have had an intense fear of darkness as children. Some of them still have a fear of the dark as adults. Darkness takes away the control and awareness that our eyesight provides us. Children who learn that mystery and uncertainty are not safe spaces come to fear the dark. It takes secure attachment to learn that we can go into the great unknown and survive its surprises.

I work primarily as a trauma therapist and a surprising large number of trauma patients have a fear of outer space. So many that I have started to ask if patients have a fear of outer space when certain things come up in therapy. Patients are shocked that I am able to detect such a specific and seemingly bizarre phobia.

I work primarily as a trauma therapist and a surprising large number of trauma patients have a fear of outer space. So many that I have started to ask if patients have a fear of outer space when certain things come up in therapy. Patients are shocked that I am able to detect such a specific and seemingly bizarre phobia.

Why outer space? We might encounter spiders, or snakes in our everyday routine but outer space is something few people have a direct encounter with. Why do our primal fears manifest as a fear of space?

At a surface level it might not seem to make sense. However space is an extended metaphor for many of our most basic fears. For one space is dark. It is cold. It is inhospitable to us. People that feel unwelcome or incapable can project this inadequacy on the impossibility of surviving in space.

On another level space represents a complete lack of control and orientation. There is no up or down. Every direction leads to the same hopeless void. There is no gravity. There is no ability to center ourselves. These extreme conditions manifest the lack of our most basic needs for orientation control and power.

Most mythological systems begin with a primal void. Water is added to the void and then land. This archetype appears in almost every creation myth. Space represents a reality stripped of the basic elements we need to survive.

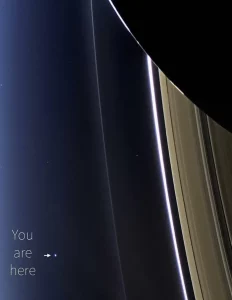

Space threatens the importance of all the things our ego needs to maintain integrity. Space represents the ultimate existential threat to all of the projects we create and all the things we identify ourselves with to make meaning. The most ambitious human projects mean nothing from the window of a rocket. Even the great wall of china is a thin line. The Vatican is a tiny dot. Our families, our careers, our religions, our sports teams… all of these things fail to matter in the midst of the cosmos. Space represents the ultimate existential annihilation. It reminds us of our ultimate limitations against the enormous scale of the universe.

When starting trauma therapy we must find our worst fear in order to confront and overcome it. Many times imagining space is the best place to start because it encompasses so many of our fears. What does space make you think of? What parts of it frighten you?

Bibliography:

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books.

- Cuarón, A. (Director). (2013). Gravity [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures.

- Eliade, M. (1963). Myth and reality. Harper & Row.

- Freud, S. (1920). A general introduction to psychoanalysis. Boni and Liveright.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence–from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

- Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma. North Atlantic Books.

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95-124). Ablex.

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Suggested Further Reading:

- “The Neuroscience of Attachment” by Allan N. Schore

- “Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy” by Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Clare Pain

- “Attachment in Psychotherapy” by David J. Wallin

- “The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation” by Stephen W. Porges

- “The Origins of Attachment Theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth” by Inge Bretherton

- “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” by Joseph Campbell (for insights into mythological archetypes)

- “Existential Psychotherapy” by Irvin D. Yalom

- “The Void in Modern Science and Cosmology” by Helge Kragh (for a scientific perspective on the concept of void)

- “Space and the American Imagination” by Howard E. McCurdy (for cultural perspectives on space)

- “An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth” by Chris Hadfield (for a firsthand account of space experiences)

0 Comments