Who Was William Morris?

William Morris was a designer known for his exquisite tapestries depicting scenes from myth, legend and medieval romance. More than decorative objects, these woven works invite the viewer into a mesmerizing world of archetypes, hidden meanings and the unconscious stirrings of the soul. Morris’s oeuvre exemplifies many of the insights of depth psychology – the recognition that powerful symbols, when engaged with imaginatively, can connect us to profound truths within the psyche.

The Mythic Dimension

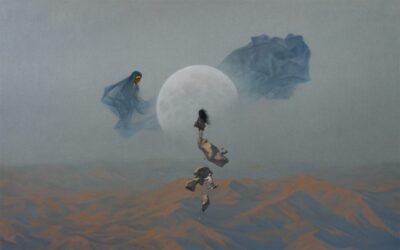

Central to Morris’s artistic vision was his immersion in the world of myth, especially Norse sagas, Arthurian legends and Greek classics. Far from mere storybook fantasies, these ancient tales, for Morris, were sacred vessels carrying the wisdom of the ages. By translating their archetypal images into the medium of tapestry, Morris sought not merely to illustrate these myths but to reanimate their spiritual power for the modern age.

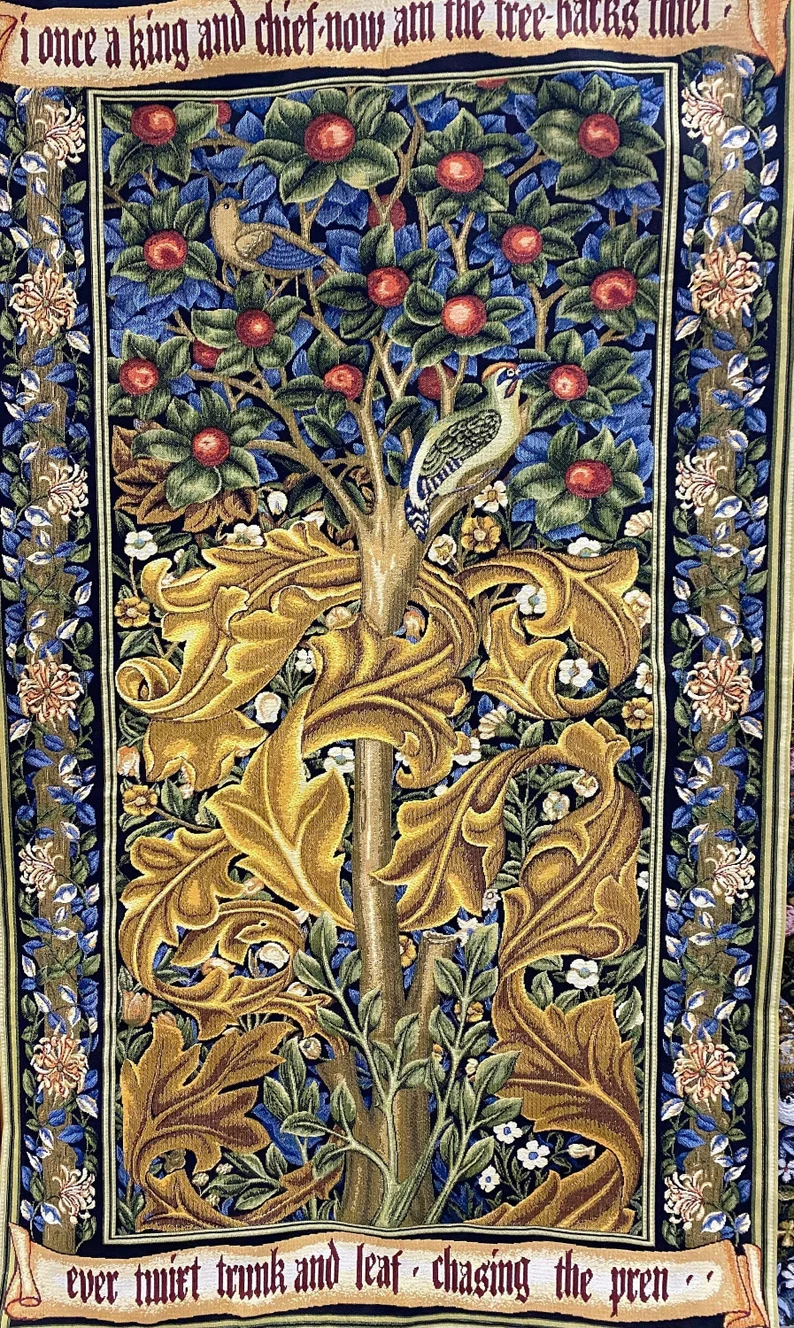

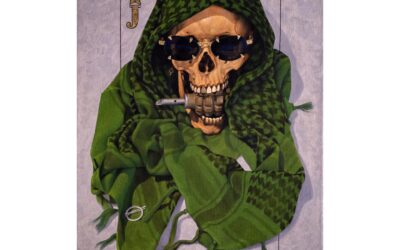

A prime example is his monumental tapestry cycle “The Story of King Picus”, based on a tale from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The tapestries at Taproot Therapy Collective in my office depict the transformation of King Picus into a woodpecker by the jealous sorceress Circe. On one level, this is an cautionary tale about the dangers of unbridled eros. But it also evokes the plight of the soul, lured by beauty into a realm of enchantment and shape-shifting.

For Carl Jung, myths were not quaint superstitions but vital expressions of the collective unconscious – those deep, inherited structures of meaning that guide the psyche’s development. In weaving life into these potent, pre-modern stories, Morris was engaging in a kind of artistic depth psychology, tapping into what poet Ted Hughes called “the mythic plane that lies beyond the gossip of history.”

The Speaking Pattern

Morris’s tapestries are remarkable not only for their mythic content but for their mesmerizing, intricate designs. Writhing vines, curling leaves, and undulating lines create a hypnotic visual field in which figures seem to float and metamorphose. Every thread contributes to a dazzling symphony of color, texture and movement that draws the eye ever inward.

In the King Picus tapestry, the doomed king’s robes swirl with elaborate patterns, as if hinting at the dizzying psychological transformation he is about to undergo. The natural imagery entwining him – fruiting vines, flitting birds, unfurling tendrils – evokes the lush, Dionysian energy of the life force itself, beautiful but perilous.

For Morris, pattern was never mere ornament but a poetic language in its own right – one that spoke wordlessly to the deep imagination. The pioneering psychologist James Hillman argued that the language of the soul is not scientific jargon but poetic metaphor rife with ambiguity and multiplicity. In his tapestries’ beguiling arabesques and metamorphic imagery, Morris found a perfect idiom to express the soul’s serpentine mysteries.

Useful and Beautiful

Morris famously strove to create objects that were both useful and beautiful. He rejected the shoddy, alienated productions of modern industry in favor of lovingly handcrafted items that served real human needs. A Morris tapestry was not only a sumptuous decoration but a functional wall-hanging that brought warmth, texture and acoustic softening to a chilly medieval hall.

Yet Morris understood that beauty, no less than usefulness, answers a deep need of the soul. Surrounded by the mass-produced ugliness of industrialism, the soul shrivels and forgets its greater potentials. Goethe called beauty “a manifestation of secret natural laws, which otherwise would have been hidden from us forever.” The shimmering sensuousness of a Morris tapestry serves the “use” of awakening the beholder to this invisible dimension singing in nature and in their own depths.

To live, work and create in beauty was thus, for Morris, a spiritual discipline – a way of attuning oneself to what Rilke called “the music of the universe”. This is the same impulse that leads modern depth psychologists to adorn their consulting rooms with evocative artwork, symbols and figurines. Like Morris’s enchanted interiors, such soul-nourishing spaces invite one into reverie, remembrance, and an openness to the numinous.

The Interior Castle

“Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” This famous Morris maxim suggests that the house – and by extension all of one’s surroundings – should be organized around the needs of interiority. The outside environment has a potent effect on our inside environment, either aiding or obstructing the soul’s thriving.

Morris’s own homes, especially his beloved Red House, were conceived as total works of art – physical extensions of his own inner world. Every element, from furniture to wall-hangings to garden design, was imbued with symbolic resonance and secret autobiographical meaning. To enter the Red House was to step inside Morris’s imagination – a site of unparalleled mythic and artistic ferment.

For depth psychology, this creation of a soul-hospitable environment is essential. Jung built his famous tower at Bollingen as a kind of alchemical vessel for the transformative work of individuation. Inside this rough-hewn refuge, he sculpted, painted and pondered the living symbols of the unconscious far from the frenzied distractions of modern life.

Morris’s tapestry-hung sanctums served a similar purpose – they were physical spaces that nurtured dream, vision and the slow, still workings of the creative process. In a world of ever-increasing noise and haste, such sites of soulful interiority are more vitally needed than ever. The rhythmic loom-spell of a Morris tapestry, encountered in solitude, might be just the catalyst one needs to venture deeper into the Interior Castle of one’s own being.

Legacy and Inspiration

Over a century after his passing, William Morris endures as a visionary figure who wove together the disparate strands of art, myth, social activism and the inner life. His work continues to beguile and inspire, offering not just visual delight but a rich psycho-spiritual nourishment.

The tapestries at Taproot Hall invite the modern pilgrim into a sanctuary of the imagination – a place where ancient stories come uncannily alive and every thread bespeaks a deeper meaning. To gaze at the metamorphosing King Picus is to look through the veil of appearances into the shape-shifting drama of the soul itself.

Like all great art, Morris’s work is a call to adventure – an invitation to leave the well-trodden paths of conscious intention and venture into the trackless forests of the unconscious. To follow Morris’s loom-ways is to discover that we too are woven into the vast, ever-unfolding tapestry of myth, meaning and the life of the world. We may be transformed in the process – but then again, transformation is what the soul most deeply desires.

Biography and Timeline

Early Life and Education

William Morris was born on March 24, 1834, in Walthamstow, England, to a wealthy middle-class family. His father, William Morris Sr., was a successful broker, and his mother, Emma Morris, was a descendant of a prominent Welsh family. Morris grew up in a comfortable household and received a classical education at Marlborough College and later at Exeter College, Oxford.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and Early Career

While at Oxford, Morris met Edward Burne-Jones, who would become his lifelong friend and artistic collaborator. Together, they were inspired by the works of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of artists who sought to revive the sincerity and spirituality of medieval and early Renaissance art. Morris and Burne-Jones joined the Brotherhood in 1856, and Morris began to develop his skills in various artistic mediums, including painting, poetry, and design.

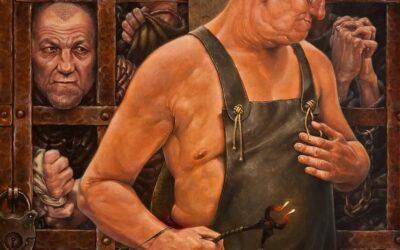

The Firm and the Arts and Crafts Movement

In 1861, Morris founded Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., a decorative arts firm that produced a wide range of handcrafted products, including furniture, stained glass, textiles, and tapestries. The firm’s work was characterized by its devotion to traditional craftsmanship, high-quality materials, and medieval-inspired designs. Morris’s innovative approach to design and his commitment to social reform helped to inspire the Arts and Crafts Movement, which sought to elevate the status of craftspeople and to promote the value of handmade goods in an increasingly industrialized world.

Literary Works and Political Activism

In addition to his work as a designer and craftsman, Morris was also a prolific writer and a passionate political activist. He wrote numerous poems, novels, and essays throughout his life, often drawing on medieval and mythological themes. His most famous literary works include “The Defence of Guenevere” (1858), “The Earthly Paradise” (1868-1870), and “News from Nowhere” (1890). Morris was also a committed socialist and a key figure in the early British socialist movement. He founded the Socialist League in 1884 and remained an active member until 1890.

Later Years and Legacy

In the later years of his life, Morris continued to work tirelessly as a designer, writer, and political activist. He founded the Kelmscott Press in 1891, which produced beautiful, hand-printed books that exemplified his commitment to traditional craftsmanship and design. Morris died on October 3, 1896, at the age of 62. His legacy lives on through his enduring influence on art, design, and politics, as well as through the countless individuals who continue to be inspired by his vision of a more beautiful and just world.

Major Works

The Red House

One of Morris’s earliest and most significant works was the Red House, a home he designed and built for himself and his family in 1860. The Red House was a collaborative effort between Morris and his friend, the architect Philip Webb. It was a manifestation of Morris’s belief that art should be integrated into everyday life and that the home should be a work of art in itself. The house featured a simple, functional design, with hand-crafted furnishings and decorations that drew inspiration from medieval art and nature. It became a gathering place for Morris’s circle of artistic friends and helped to establish his reputation as a leading figure in the British arts scene.

The Kelmscott Chaucer

In 1896, near the end of his life, Morris published his masterpiece, the Kelmscott Chaucer. This monumental work was a hand-printed edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s “The Canterbury Tales,” featuring 87 illustrations by Edward Burne-Jones and elaborate borders and initials designed by Morris himself. The book was printed using traditional methods on handmade paper, with a custom-designed typeface based on medieval manuscript lettering. Only 425 copies were produced, making it a true collector’s item. The Kelmscott Chaucer is considered one of the finest examples of book design and craftsmanship in the history of printing.

The Woodpecker Tapestry

Among Morris’s many tapestries, the Woodpecker Tapestry holds a special place. Woven in 1885, it depicts a scene from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” in which King Picus is transformed into a woodpecker by the sorceress Circe. The tapestry is a stunning example of Morris’s skill as a designer and weaver, with intricate patterns and vibrant colors that bring the mythical scene to life. The Woodpecker Tapestry hangs in Kelmscott Manor, Morris’s beloved country home, and serves as a testament to his enduring fascination with mythology and the natural world.

Background and Themes

The Influence of Medieval Art and Literature

Morris’s artistic vision was deeply influenced by his love of medieval art and literature. He was particularly drawn to the rich symbolism and storytelling of medieval tapestries, which he saw as a way to connect with the collective unconscious of humanity. Morris’s own tapestries often depicted scenes from medieval romances, such as the Arthurian legends, as well as from classical mythology. He believed that these stories contained timeless truths about the human experience and that by engaging with them through art, individuals could gain a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them.

The Importance of Craftsmanship

Morris was a passionate advocate for the value of craftsmanship in an age of increasing industrialization. He believed that the mass production of goods had led to a decline in quality and a disconnection between the maker and the object. In his own work, Morris emphasized the importance of traditional techniques and materials, and he sought to create objects that were both beautiful and functional. He saw the act of creation as a spiritual practice, one that required patience, skill, and a deep connection to the natural world.

The Role of Nature in Morris’s Work

Nature was a constant source of inspiration for Morris, and his designs often featured intricate patterns based on plants, animals, and other natural forms. He believed that by surrounding oneself with the beauty of nature, one could find a sense of peace and harmony in a chaotic world. Morris’s reverence for nature was also tied to his socialist beliefs, as he saw the destruction of the natural environment as a symptom of the greed and exploitation of industrial capitalism.

Morris’s Socialist Vision

Throughout his life, Morris was a committed socialist who believed in the power of art and craft to transform society. He saw the inequalities and injustices of Victorian England as a result of a system that valued profit over people, and he worked tirelessly to promote a vision of a more equitable and sustainable world. Morris’s socialist beliefs were deeply intertwined with his artistic practice, as he sought to create objects that were accessible to all and that reflected the values of community, cooperation, and shared ownership.

Jungian Interpretation

The Collective Unconscious in Morris’s Tapestries

From a Jungian perspective, Morris’s tapestries can be seen as a window into the collective unconscious of humanity. Jung believed that certain symbols and archetypes were universal and that they appeared in the myths, legends, and artwork of cultures around the world. By drawing on these ancient stories and symbols in his tapestries, Morris was tapping into a deep well of shared meaning and experience. The figures and scenes depicted in his work, such as the transformation of King Picus into a woodpecker, can be seen as manifestations of the archetypal patterns that shape our understanding of the world and ourselves.

The Process of Individuation

Jung’s concept of individuation, the lifelong process of becoming oneself, is also relevant to Morris’s artistic practice. For Jung, individuation involved a deep engagement with the unconscious mind, a willingness to confront one’s shadows and integrate them into a more whole and authentic sense of self. Morris’s dedication to his craft, his immersion in the world of myth and symbol, and his commitment to living a life guided by beauty and meaning can all be seen as expressions of this process. By creating works of art that were deeply personal and yet universally resonant, Morris was engaging in a form of self-discovery and self-expression that mirrored the individuation journey.

The Integration of the Anima

Another key concept in Jungian psychology is the anima, the feminine aspect of the male psyche. Jung believed that for men to become fully individuated, they needed to acknowledge and integrate their anima, which often appeared in dreams and artwork as a mysterious and alluring feminine figure. In Morris’s work, the anima can be seen in his frequent depiction of strong, complex female characters from myth and legend, such as Guinevere, Medea, and Circe. By engaging with these figures through his art, Morris was exploring the feminine dimensions of his own psyche and bringing them into greater consciousness.

The Importance of the Numinous

For Jung, the numinous referred to the sense of awe, mystery, and sacredness that one experiences in the presence of the divine. He believed that engaging with the numinous was essential for psychological health and that it could be accessed through religious practice, dream work, and artistic creation. Morris’s deep reverence for beauty, his fascination with the mythic and the symbolic, and his dedication to his craft can all be seen as ways of connecting with the numinous. By creating works of art that were imbued with a sense of wonder and mystery, Morris was inviting others to share in this experience of the sacred.

Legacy and Influence

Morris’s artistic and social legacy continues to inspire and influence creators and thinkers around the world. His emphasis on craftsmanship, his commitment to integrating art into everyday life, and his vision of a more just and sustainable society have all had a profound impact on subsequent generations of artists and activists.

In the world of design, Morris’s ideas about the importance of simplicity, functionality, and natural beauty have been taken up by movements such as modernism, minimalism, and eco-design. His textile patterns and wallpaper designs continue to be popular and are frequently reproduced and adapted by contemporary designers.

Morris’s influence can also be seen in the work of depth psychologists and art therapists, who often draw on his ideas about the power of symbol and myth to connect with the unconscious mind. The use of tapestry-making and other craft practices as a form of therapeutic self-expression owes much to Morris’s pioneering work in this area.

Perhaps most importantly, Morris’s legacy lives on in the countless individuals who continue to be inspired by his example of a life dedicated to beauty, meaning, and social justice. In a world that often feels increasingly fragmented and disconnected, Morris’s vision of art as a unifying force and a means of personal and collective transformation remains as relevant as ever. As we seek to navigate the challenges of our own time, we can look to Morris as a guide and a reminder of the enduring power of the human spirit to create, to imagine, and to make the world anew.

0 Comments