“The highest knowledge is to know that we are surrounded by mystery. Neither knowledge nor hope for the future can be the pivot of our life or determine its direction. It is intended to be solely determined by our allowing ourselves to be gripped by the ethical God, who reveals Himself in us, and by our yielding our will to His.”

– Rudolf Steiner

Who was Rudolf Steiner?

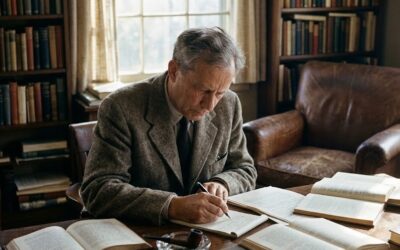

Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) was an Austrian philosopher, educator, and spiritual thinker whose ideas and teachings laid the foundation for the anthroposophical movement. Born in Kraljevec, Austria-Hungary (now Croatia), Steiner showed a keen intellect and a deep interest in the spiritual dimension of life from an early age.

Steiner’s early career was marked by his work as a scholar and editor of the scientific writings of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Through his study of Goethe’s scientific and philosophical works, Steiner developed a unique perspective on the relationship between science, art, and spirituality, which would later form the basis of his anthroposophical teachings.

In the early 20th century, Steiner began to develop his own spiritual philosophy, which he called anthroposophy (from the Greek “anthropos,” meaning human, and “sophia,” meaning wisdom). Anthroposophy seeks to integrate scientific, artistic, and spiritual approaches to understanding the nature of the human being and the universe.

Steiner’s work and teachings encompass a wide range of fields, including education, agriculture, medicine, architecture, and the arts. He is perhaps best known for his contributions to alternative education, particularly through the Waldorf school movement, which he founded in 1919.

“Our highest endeavor must be to develop free human beings who are able of themselves to impart purpose and direction to their lives. The need for imagination, a sense of truth, and a feeling of responsibility—these three forces are the very nerve of education.” – Rudolf Steiner

Key Concepts in Steiner’s Anthroposophy:

-

The Threefold Nature of the Human Being:

Central to Steiner’s anthroposophy is the idea that the human being is composed of three distinct but interrelated aspects: the physical body, the soul (or astral body), and the spirit (or ego). Steiner saw these aspects as reflecting the threefold nature of the universe itself, which he described as consisting of the physical world, the world of soul or consciousness, and the world of spirit.

According to Steiner, the task of human evolution is to bring these three aspects into harmony and balance, so that the individual can become a free and self-determined being, capable of fulfilling their unique destiny and purpose in the world.

-

The Evolution of Consciousness:

Another key concept in Steiner’s anthroposophy is the idea of the evolution of human consciousness. Steiner believed that humanity has undergone a series of stages in the development of consciousness, from an ancient, dreamlike state of unity with the spiritual world to the modern, individualized consciousness of the present day.

Steiner saw this evolution as a necessary and purposeful process, through which humanity is gradually awakening to its true spiritual nature and its role in the cosmic order. He believed that the next stage in this evolution would involve the development of a new, intuitive form of consciousness, which he called “Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition.”

-

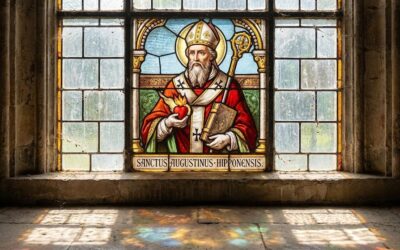

The Spiritual World and the Being of Christ:

Steiner’s anthroposophy is deeply rooted in a spiritual worldview that recognizes the existence of a higher, spiritual reality beyond the physical world. He believed that this spiritual world is populated by a vast hierarchy of spiritual beings, ranging from the highest divine beings to the nature spirits and elemental beings that work in the natural world.

Central to Steiner’s spiritual cosmology is the figure of Christ, whom he saw not merely as a historical person, but as a cosmic being who represents the highest stage of human evolution. Steiner believed that through the “Mystery of Golgotha” (the death and resurrection of Christ), humanity was given the possibility of overcoming death and attaining a new, spiritual form of existence.

-

The Practice of Spiritual Science:

For Steiner, anthroposophy was not merely a theoretical or philosophical system, but a path of knowledge and practice that could lead to direct experience of the spiritual world. He developed a variety of spiritual exercises and meditations designed to awaken the higher faculties of Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition, and to enable the individual to perceive and communicate with spiritual realities.

Steiner emphasized that this path of spiritual science was not a matter of blind faith or dogmatic belief, but a rigorous and systematic approach to the study of the spiritual world, based on clear thinking, keen observation, and disciplined inner development.

-

The Social and Cultural Implications of Anthroposophy:

Steiner’s anthroposophy was not merely a personal spiritual path, but a vision for the renewal and transformation of human society and culture. He believed that the insights and practices of anthroposophy could be applied to all areas of human life, from education and agriculture to medicine and the arts.

Steiner was particularly concerned with the question of social renewal and the creation of a more just and harmonious social order. He developed the idea of the “threefold social order,” which envisions a society based on the principles of freedom in cultural life, equality in political life, and brotherhood in economic life.

Rudolf Steiner’s Architectural Vision:

One of the most striking and visible manifestations of Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophical philosophy is the unique style of architecture that he developed and promoted. Steiner’s architectural vision was based on the idea that the built environment should reflect and support the spiritual and social needs of the human being, and that it should be created in harmony with the forces and rhythms of the natural world.

Steiner’s approach to architecture was deeply influenced by his concept of the threefold nature of the human being and the universe. He believed that buildings should be designed to reflect and support the three aspects of the human being – the physical, the soul, and the spirit – and that they should be created in a way that harmonizes with the threefold nature of the universe.

One of the most distinctive features of Steiner’s architecture is the use of organic, flowing forms and the avoidance of straight lines and right angles. Steiner believed that these organic forms were more in tune with the living, dynamic forces of nature, and that they could help to create a sense of movement, growth, and transformation in the built environment.

Another key aspect of Steiner’s architectural vision was the use of color and light to create specific moods and atmospheres in different spaces. Steiner believed that color and light could have a powerful effect on the human psyche, and that they could be used to support different types of activities and experiences.

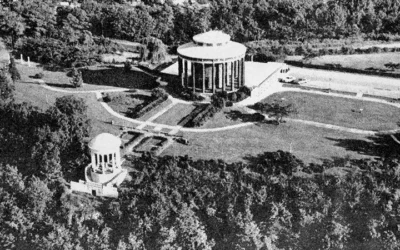

For example, in Steiner’s design for the first Goetheanum, a cultural center and headquarters for the anthroposophical movement, he used a palette of warm, earthy colors and soft, diffuse light to create a sense of reverence and contemplation in the main auditorium. In contrast, in the workshops and studios, he used brighter, more vibrant colors and stronger, more focused light to create a sense of energy and creativity.

Steiner’s architectural vision also emphasizes the importance of natural materials, such as wood, stone, and clay, and the use of traditional building techniques and craftsmanship. He believed that these natural materials and techniques could help to create a sense of warmth, texture, and authenticity in the built environment, and that they could support the health and well-being of the people who lived and worked in these spaces.

One of the most famous examples of Steiner’s architectural vision is the second Goetheanum, which was built after the first Goetheanum was destroyed by fire in 1922. The second Goetheanum is a striking example of Steiner’s organic, sculptural style, with its curving, double-domed roof and its richly colored, abstract stained-glass windows.

Other notable examples of Steiner’s architecture include the first Waldorf school in Stuttgart, Germany, which was designed to support the holistic, child-centered approach to education that Steiner developed, and the Anthroposophical Medical Center in Arlesheim, Switzerland, which was designed to support the integrative, holistic approach to medicine that Steiner advocated.

Steiner’s architectural vision has had a significant impact on the development of organic and ecological architecture in the 20th and 21st centuries. His ideas about the importance of creating buildings that are in harmony with the natural world and that support the spiritual and social needs of the human being have inspired generations of architects and designers, and continue to be relevant and influential today.

In many ways, Steiner’s architectural vision can be seen as a reflection of his broader philosophical and spiritual worldview. Just as he sought to create a holistic, integrative approach to education, medicine, and social life, he also sought to create a built environment that was in harmony with the forces and rhythms of the natural world and that supported the health, well-being, and spiritual development of the human being.

By designing buildings that reflect the threefold nature of the human being and the universe, that use natural materials and organic forms, and that create specific moods and atmospheres through the use of color and light, Steiner hoped to create a built environment that could support the evolution of human consciousness and the creation of a more just and harmonious social order.

In this sense, Steiner’s architectural vision can be seen as a powerful example of how the insights and principles of anthroposophy can be applied to the practical, tangible world of design and construction, and of how the built environment can be a vehicle for the expression and realization of spiritual and social ideals.

The Relevance of Steiner for Psychology and Spirituality:

Steiner’s anthroposophical vision has important implications for psychology and spirituality, particularly in the fields of developmental psychology, transpersonal psychology, and holistic approaches to mental health and well-being.

One of the key insights of Steiner’s work is the idea that human development is a lifelong process that encompasses not only the physical and psychological dimensions but also the spiritual dimension of the human being. Steiner’s model of the threefold nature of the human being provides a framework for understanding the interrelationship between body, soul, and spirit, and the ways in which these aspects of the self evolve and integrate over the course of the lifespan.

This holistic understanding of human development has important implications for education, particularly in the Waldorf school movement, which Steiner founded. Waldorf education seeks to support the healthy development of the whole child, not merely the intellect, but also the emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions of the self.

Steiner’s concept of the evolution of consciousness also has important implications for transpersonal psychology and the study of spiritual experiences and practices. Steiner’s model of the stages of human consciousness provides a framework for understanding the different modes of perception and experience that are available to the human being, from the sensory and rational to the imaginative, inspired, and intuitive.

This understanding can help to validate and contextualize the wide range of spiritual experiences and practices that are found in different cultures and traditions, and to provide a basis for the study of the transformative potential of these practices.

Finally, Steiner’s emphasis on the practice of spiritual science and the cultivation of the higher faculties of Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition has important implications for the field of mental health and well-being. Steiner’s approach suggests that the development of these faculties is not merely a matter of personal growth or self-improvement, but a fundamental aspect of human health and wholeness.

By engaging in practices such as meditation, artistic creation, and the study of the spiritual world, individuals can awaken their latent spiritual capacities and tap into a deeper source of meaning, purpose, and resilience in the face of life’s challenges. This holistic approach to mental health recognizes the importance of addressing not only the symptoms of psychological distress but also the underlying spiritual needs and potentials of the human being.

Comparison between Steiner and Carl Jung:

Rudolf Steiner and Carl Jung were two of the most influential and innovative thinkers of the early 20th century, and there are many interesting parallels and differences between their ideas and approaches.

One of the key similarities between Steiner and Jung is their emphasis on the importance of the spiritual dimension of human experience. Both thinkers saw the spiritual world as a fundamental aspect of reality, and both sought to develop methods and practices for exploring and understanding this dimension of experience.

However, there are also significant differences in the way that Steiner and Jung approached the spiritual world. Steiner’s anthroposophy is based on a detailed and systematic cosmology that describes the evolution of human consciousness and the hierarchical structure of the spiritual world. Jung, on the other hand, was more interested in the psychological and symbolic dimensions of spiritual experience, and his approach was more open-ended and exploratory.

Another key difference between Steiner and Jung is their understanding of the nature of the unconscious. For Jung, the unconscious was a key concept, and he saw it as a vast, creative realm that contains both personal and collective elements. Steiner, on the other hand, did not use the concept of the unconscious in the same way, and his understanding of the inner world of the human being was based more on the idea of the threefold nature of the self and the evolution of consciousness.

Steiner, through his anthroposophical philosophy, aimed to develop a spiritual science that could stand alongside natural science. He believed that by cultivating higher states of consciousness, individuals could gain direct, objective knowledge of spiritual realities. This meant that Steiner was operating as a prophet, who through spiritual encounter, would find insights to transform science. Steiner’s methods involved a systematic training of the mind and senses to perceive the subtle dimensions of existence, which he believed were as real and lawful as the physical world studied by conventional science. Most of Steiner’s insights, such as bio dynamic farming, have been prove to be pseudo scientific.

On the other hand, Jung approached the problem from the perspective of depth psychology. He recognized the importance of subjective, symbolic experiences in shaping the human psyche and believed that these experiences could not be adequately understood through the lens of materialistic science alone. Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious suggested that there were universal, archetypal patterns that transcended individual experience and connected humanity to a deeper, spiritual reality.

Both Steiner and Jung challenged the dominant paradigm of their time, which increasingly viewed the world through a purely materialistic and mechanistic lens. They argued that this perspective was incomplete and that a true understanding of reality required a recognition of the subjective, phenomenological dimension of human experience.

However, their methods for investigating this dimension differed. Steiner’s approach was more mystical, arguing that only by getting rid of objective senses could we feel the true spiritual center that would then inform science and objectivity. He believed that through disciplined meditation and the cultivation of higher states of consciousness, individuals could gain direct, objective knowledge of the spiritual world.

Jung, in contrast, focused more on the symbolic and archetypal dimensions of the psyche. He believed that by exploring the depths of the unconscious mind through techniques such as dream analysis and active imagination, individuals could gain insight into the spiritual dimensions of existence.

Despite these differences, both Steiner and Jung were pioneers in the effort to bring a more holistic and integrative perspective to the study of human experience. They recognized the limitations of a purely empirical approach and sought to develop new methods for investigating the subjective, phenomenological dimensions of reality. In doing so, they helped to lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between science and spirituality.

Carl Jung’s Reaction to Steiner and

Carl Jung wrote to a friend in 1935″:

…I have read a few books on anthroposophy and a fair number on theosophy. I have also got to know very many anthroposophists and theosophists and have always discovered to my regret that these people imagine all sorts of things and assert all sorts of things for which they are quite incapable of offering any proof. I have no prejudices against the greatest marvels if someone gives me the necessary proofs. Nor shall I hesitate to stand up for the truth if I know it can be proved. But I shall guard against adding to the number of those who use unproven assertions to erect a world system no stone of which rests on the surface of this earth. So long as Steiner is or was not able to understand the Hittite inscriptions yet understood the language of Atlantis which nobody knows existed, there is no reason to get excited about anything that Herr Steiner has said…

Jung had the same issues with Steiner that he had with Blavatsky, that Steiner had split from and Assagioli. Even though Jung was both broad and open minded he did try and root assumptions in some kind of empirical or reproducible observable phenomenon. Jung stuck to that out look even when investigating metaphysics or the paranormal. People who made claims without evidence where acting on unconscious intuition in a way that made Jung uncomfortable. Jung was uncomfortable with those that “went native” in the unconscious. He preferred to deal with those open to the experience of the unconscious but prescient enough to see the experience for what it was and return to the bounds of the ego. Even though these thinkers get lumped together often, Jung was in quite a different world from Manly P. Hall, Roberto Assagioli, Rudolph Steiner, Helena Blavatsky and the majority of the New Age prophets and gurus. This did him few favors when these philosophies were on the rise.

Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy and Carl Jung’s analytical psychology share some similarities in their understanding of the visionary imagination and its role in spiritual growth and transformation. Both thinkers placed great emphasis on the importance of engaging with the imagination as a means of accessing deeper truths about the self and the world. Steiner’s concept of Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition as higher stages of cognition resonates with Jung’s idea of the active imagination as a tool for engaging with the unconscious. However, there are also significant differences between Steiner and Jung’s approaches. Steiner’s understanding of the imagination was more overtly spiritual and esoteric, grounded in his claimed clairvoyant abilities and his belief in the existence of multiple spiritual worlds and beings. Jung, on the other hand, sought to ground his understanding of the psyche in empirical reality and was more cautious about making metaphysical claims without sufficient evidence.

Similarly, while both Steiner and Jung recognized the importance of the self as a central organizing principle, their understandings of the nature of the self differed in some key respects. Steiner’s anthroposophy posited the existence of a higher self or ego that transcended the limitations of the individual personality and was seen as a microcosmic reflection of the macrocosmic Logos or cosmic intelligence. Jung’s concept of the self, while also transcending the ego, was more psychologically grounded and less explicitly tied to a specific cosmological framework. Moreover, Steiner’s understanding of the Logos was more anthropocentric than Jung’s, seeing it as a force that could be actively engaged with and influenced by human consciousness. Jung, in contrast, tended to see the Logos as a more impersonal and autonomous principle that transcended human understanding.

Jungian Criticisms of New Age and Post Theosophical Figures like Steiner

David Tacey’s book “Jung and the New Age” explores the relationship between Carl Jung’s ideas and the New Age movement, highlighting both the similarities and differences between the two. Tacey argues that Jung’s ideas have been a significant influence on the New Age movement, particularly his concepts of individuation, the collective unconscious, and archetypes. However, despite Jung’s influence, Tacey suggests that many New Age thinkers have misinterpreted or oversimplified Jung’s complex ideas, often taking them out of context or ignoring their psychological grounding. Tacey also highlights Jung’s own critiques of the New Age movement, including his skepticism towards ungrounded spiritual claims and his emphasis on the importance of maintaining a strong ego and connection to reality. The book discusses the potential dangers of the New Age movement, such as the risk of spiritual bypassing, narcissism, and the avoidance of psychological and emotional challenges. Tacey argues for a more balanced approach to spirituality that incorporates both Jung’s ideas and the insights of the New Age movement while remaining grounded in psychological and empirical reality. Finally, Tacey explores the ongoing relevance of Jung’s ideas in the contemporary world and suggests that a renewed engagement with his work could help to foster a more mature and integrated approach to spirituality and personal growth.

Regarding James Hillman, Tacey notes that Hillman, a post-Jungian thinker, critiqued the idea of the self as a fixed, unchanging entity. Instead, Hillman proposed the concept of the “polytheistic psyche,” which suggests that the self is composed of multiple, diverse aspects or “gods.” Tacey argues that Hillman’s perspective challenges the New Age notion of the self as a unified, perfectable being and instead emphasizes the importance of embracing the complexity and diversity within oneself. Tacey also draws on the ideas of Charles Darwin to critique the New Age understanding of the self. He suggests that the New Age movement often promotes a view of the self as separate from and superior to nature, whereas Darwin’s theory of evolution emphasizes the interconnectedness of all life forms. Tacey argues that a more grounded and realistic approach to the self should acknowledge the ways in which humans are embedded within the natural world and shaped by evolutionary processes. Finally, Tacey discusses the influence of William Blake, the English poet and visionary, on Jung’s understanding of the self. Blake’s work often explored the tension between the individual self and the larger, cosmic self, and Tacey suggests that this theme resonates with Jung’s concept of individuation. However, Tacey also notes that Blake’s vision of the self was deeply spiritual and imaginative, whereas Jung sought to ground his understanding of the self in psychological and empirical reality.

In his book “Re-Visioning Psychology,” Hillman briefly discusses Steiner in the context of the history of ideas that have influenced modern psychology. He acknowledges Steiner’s contributions to the understanding of the imagination and the spiritual dimensions of the psyche, alongside other thinkers such as William Blake, Emanuel Swedenborg, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. However, Hillman’s own approach to psychology differed significantly from Steiner’s anthroposophy. Hillman was more focused on the archetypal dimensions of the psyche and the importance of embracing the multiplicity of the self, rather than seeking to integrate the self around a central, spiritual core as Steiner did.

Steiner’s Influence on Education and Health Culture

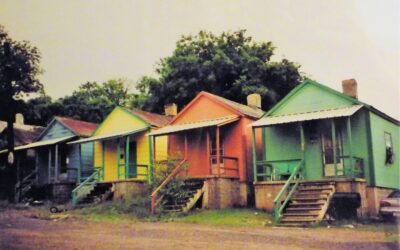

Rudolf Steiner’s influence on wellness and holistic culture in Austria and Germany cannot be overstated. In the aftermath of World War I, many people in these countries were left devastated and disillusioned by the horrors they had witnessed and the defeat they had suffered. The existential crisis that followed led many to search for meaning and purpose beyond the confines of traditional philosophical and religious frameworks.

Steiner’s anthroposophical philosophy offered a compelling alternative for those seeking a deeper connection to the spiritual and natural world. His approach emphasized the unity of mind, body, and spirit, and sought to integrate scientific and spiritual perspectives into a holistic understanding of the human experience.

One of the key aspects of Steiner’s philosophy that resonated with many people in the post-war period was his emphasis on the healing power of nature. Steiner believed that by cultivating a deeper connection to the natural world, individuals could tap into a source of spiritual nourishment and renewal that could help them overcome the trauma and despair of the war years.

This idea found practical expression in the development of anthroposophical medicine, which sought to integrate conventional medical treatments with a holistic approach that recognized the importance of the patient’s spiritual and emotional well-being. Steiner’s followers also established a network of schools, farms, and communities that aimed to put his principles into practice and create a more harmonious and sustainable way of life.

For many people in Austria and Germany, Steiner’s philosophy offered a powerful and appealing alternative to the nihilism and despair that characterized much of the intellectual and cultural landscape of the post-war period. His emphasis on the spiritual dimensions of existence, the healing power of nature, and the importance of community and social responsibility struck a deep chord with those who were seeking a more meaningful and fulfilling way of life.

Over time, Steiner’s influence spread beyond the confines of anthroposophical circles and began to shape the broader wellness and holistic culture in Austria and Germany. His ideas about the importance of organic agriculture, holistic education, and natural medicine became increasingly mainstream, and his philosophy continues to inspire and inform the work of many practitioners and advocates of holistic health and wellness today.

In many ways, Steiner’s legacy in Austria and Germany can be seen as a testament to the enduring power of his vision and the deep resonance of his ideas with the human yearning for meaning, purpose, and connection in the face of adversity and despair. His philosophy offered a pathway to healing and renewal that continue to inspire and guide many people in their quest for a more holistic and fulfilling way of life.

Steiner’s Legacy in Education

The wellness culture and Waldorf schools inspired by Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophical philosophy have not only survived but thrived in the decades since their inception. Today, they continue to be important and influential aspects of the cultural landscape in Austria, Germany, and beyond.

Waldorf education, in particular, has become a global movement, with over 1,000 schools and 2,000 kindergartens operating in more than 60 countries worldwide. These schools are based on Steiner’s educational philosophy, which emphasizes the importance of holistic learning, creative expression, and the cultivation of the child’s unique potential.

In Waldorf schools, academic subjects are integrated with artistic and practical activities, such as music, drama, and handwork, in order to engage the child’s whole being and foster a love of learning. The curriculum is designed to be developmentally appropriate, with a focus on experiential learning and the cultivation of imagination and creativity.

The success of Waldorf education can be attributed in part to its ability to adapt to changing times and cultural contexts while remaining true to its core principles. Waldorf schools have become increasingly diverse and inclusive, serving families from a wide range of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Similarly, the wellness culture inspired by Steiner’s philosophy has continued to evolve and expand over the years. Anthroposophical medicine, which integrates conventional medical treatments with a holistic approach to health and healing, has gained increasing recognition and acceptance within the mainstream medical community.

Other aspects of Steiner’s philosophy, such as biodynamic agriculture and the use of natural materials in architecture and design, have also gained wider recognition and adoption. Today, there are numerous intentional communities, eco-villages, and sustainable living projects around the world that are inspired by Steiner’s ideas and seek to put them into practice.

The enduring appeal of Steiner’s philosophy can be attributed to its ability to speak to the deepest yearnings of the human spirit for meaning, purpose, and connection. In an age of increasing alienation, fragmentation, and ecological crisis, Steiner’s vision of a holistic and harmonious relationship between the individual, society, and the natural world offers a compelling alternative.

The survival and growth of the wellness culture and Waldorf schools inspired by Steiner’s philosophy is a testament to the power of his ideas and the dedication of those who have worked to put them into practice. As the world continues to face new challenges and uncertainties, it is likely that Steiner’s legacy will continue to inspire and guide those who seek a more holistic and meaningful way of life.

Timeline of Steiner’s Life and Work:

1861 – Rudolf Steiner is born in Kraljevec, Austria-Hungary (now Croatia).

1879 – Steiner enrolls at the Vienna Institute of Technology to study mathematics and natural sciences.

1883 – Steiner becomes the editor of Goethe’s scientific writings at the Goethe Archives in Weimar, Germany.

1891 – Steiner earns his Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Rostock, Germany.

1894 – Steiner publishes his first major philosophical work, “The Philosophy of Freedom.”

1902 – Steiner becomes the head of the German section of the Theosophical Society.

1912 – Steiner breaks with the Theosophical Society and founds the Anthroposophical Society.

1913 – Steiner designs and oversees the construction of the first Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland.

1919 – Steiner founds the first Waldorf school in Stuttgart, Germany.

1922 – The first Goetheanum is destroyed by fire.

1923 – Steiner founds the General Anthroposophical Society and begins the design and construction of the second Goetheanum.

1924 – Steiner gives his last public lecture and becomes increasingly ill.

1925 – Rudolf Steiner dies in Dornach, Switzerland.

Steiner’s Bibliography

Philosophy of Freedom (1894)

Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the Cosmos (1904)

How to Know Higher Worlds (1904)

Cosmic Memory: Prehistory of Earth and Man (1904)

Atlantis and Lemuria (1904)

The Education of the Child in the Light of Anthroposophy (1907)

An Outline of Esoteric Science (1909)

Four Mystery Dramas (1910-1913)

The Spiritual Guidance of the Individual and Humanity (1911)

A Road to Self-Knowledge (1912)

The Threshold of the Spiritual World (1913)

The Riddles of Philosophy (1914)

Occult Science: An Outline (1910)

The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity (1916)

Riddles of the Soul (1917)

Fundamentals of Therapy (1925)

Karmic Relationships, Volumes I-VIII (1924-1934)

The Story of My Life (1924-1925)

Anthroposophical Leading Thoughts (1924-1925)

The Foundation Stone Meditation (1924)

The Calendar of the Soul (1925)

The First Class Lessons and Mantras (1924)

Eurythmy as Visible Speech (1924)

The Essentials of Education (1924)

True and False Paths in Spiritual Investigation (1924)

The Healing Process: Spirit, Nature and Our Bodies (1920)

Nutrition and Health (1924)

The Christian Mystery (1923)

The Cycle of the Year as Breathing Process of the Earth (1923)

The Festivals and Their Meaning: Christmas, Easter, Ascension and Pentecost (1915-1918)

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Further Reading:

- Ahern, G. (2009). Sun at Midnight: The Rudolf Steiner Movement and Gnosis in the West. James Clarke & Co.

- Dane, R. (2007). The Artist’s Secret: Rudolf Steiner and Anthroposophy. Hudson Hills.

- Easton, S.C. (1980). Rudolf Steiner: Herald of a New Epoch. Anthroposophic Press.

- Hemleben, J. (2013). Rudolf Steiner: An Illustrated Biography. Sophia Books.

- Lachman, G. (2007). Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and Work. Tarcher/Penguin.

- McDermott, R.A. (2009). The New Essential Steiner: An Introduction to Rudolf Steiner for the 21st Century. Lindisfarne Books.

- Selg, P. (2012). Rudolf Steiner: Life and Work. SteinerBooks.

- Ullrich, H. (2008). Rudolf Steiner. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Wilson, C. (1985). Rudolf Steiner: The Man and His Vision. Aquarian Press.

- Zander, H. (2007). Anthroposophie in Deutschland: Theosophische Weltanschauung und gesellschaftliche Praxis 1884–1945. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Tacey, D. (2001). Jung and the New Age. Routledge.

- Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

- Oberman, H.A. (2003). The Two Reformations: The Journey from the Last Days to the New World. Yale University Press.

- Goethe, J.W. (1790). The Metamorphosis of Plants. [Steiner’s work on Goethe’s scientific writings]

- Blavatsky, H.P. (1888). The Secret Doctrine. Theosophical Publishing Company. [For context on Theosophy]

- Assagioli, R. (1965). Psychosynthesis: A Manual of Principles and Techniques. Hobbs, Dorman & Company. [For comparison with other spiritual psychologies]

- Hall, M.P. (1928). The Secret Teachings of All Ages. H.S. Crocker Company. [For context on esoteric traditions]

- Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species. John Murray. [Mentioned in relation to New Age critiques]

- Blake, W. (1794). Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [Mentioned in relation to Jung’s understanding of the self

Main Ideas and Key Points:

- Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) was an Austrian philosopher, educator, and spiritual thinker who founded anthroposophy, a spiritual philosophy integrating science, art, and spirituality.

- Key concepts in Steiner’s anthroposophy include:

- The threefold nature of the human being (physical body, soul, spirit)

- The evolution of consciousness

- The existence of a spiritual world and the importance of Christ

- The practice of spiritual science

- Steiner’s work influenced various fields, including:

- Education (Waldorf schools)

- Agriculture (biodynamic farming)

- Medicine (anthroposophical medicine)

- Architecture (organic, flowing forms)

- Steiner’s architectural vision emphasized organic forms, natural materials, and the use of color and light to create specific atmospheres.

- Steiner’s ideas have implications for psychology and spirituality, particularly in developmental and transpersonal psychology.

- There are similarities and differences between Steiner’s work and that of Carl Jung:

- Both emphasized the importance of the spiritual dimension

- Jung was more grounded in empirical reality and psychological concepts

- Steiner’s approach was more mystical and based on claimed clairvoyant abilities

- Steiner’s influence on wellness and holistic culture in Austria and Germany was significant, especially after World War I.

- Waldorf education has become a global movement, with over 1,000 schools worldwide.

- Steiner’s ideas continue to influence various fields, including sustainable living and alternative medicine.

- Critics, including Jung, have questioned Steiner’s unproven assertions and lack of empirical evidence for some of his claims.

- Steiner’s work has been both influential and controversial, with ongoing debates about its scientific validity and practical applications.

0 Comments