The Expansive Decadent Ego of the Animus and the Introspective Bust and Decline of the Anima as Parts of Empire

Cultures wax and wane. Empires that seem like part of the cosmos itself fall like gunshot victims into a pool or lines on a bar chart. It is the rare work that can speak to both the sparkle of spectacle and the timeless inevitable real it distracts us from.

Cultures wax and wane. Empires that seem like part of the cosmos itself fall like gunshot victims into a pool or lines on a bar chart. It is the rare work that can speak to both the sparkle of spectacle and the timeless inevitable real it distracts us from.

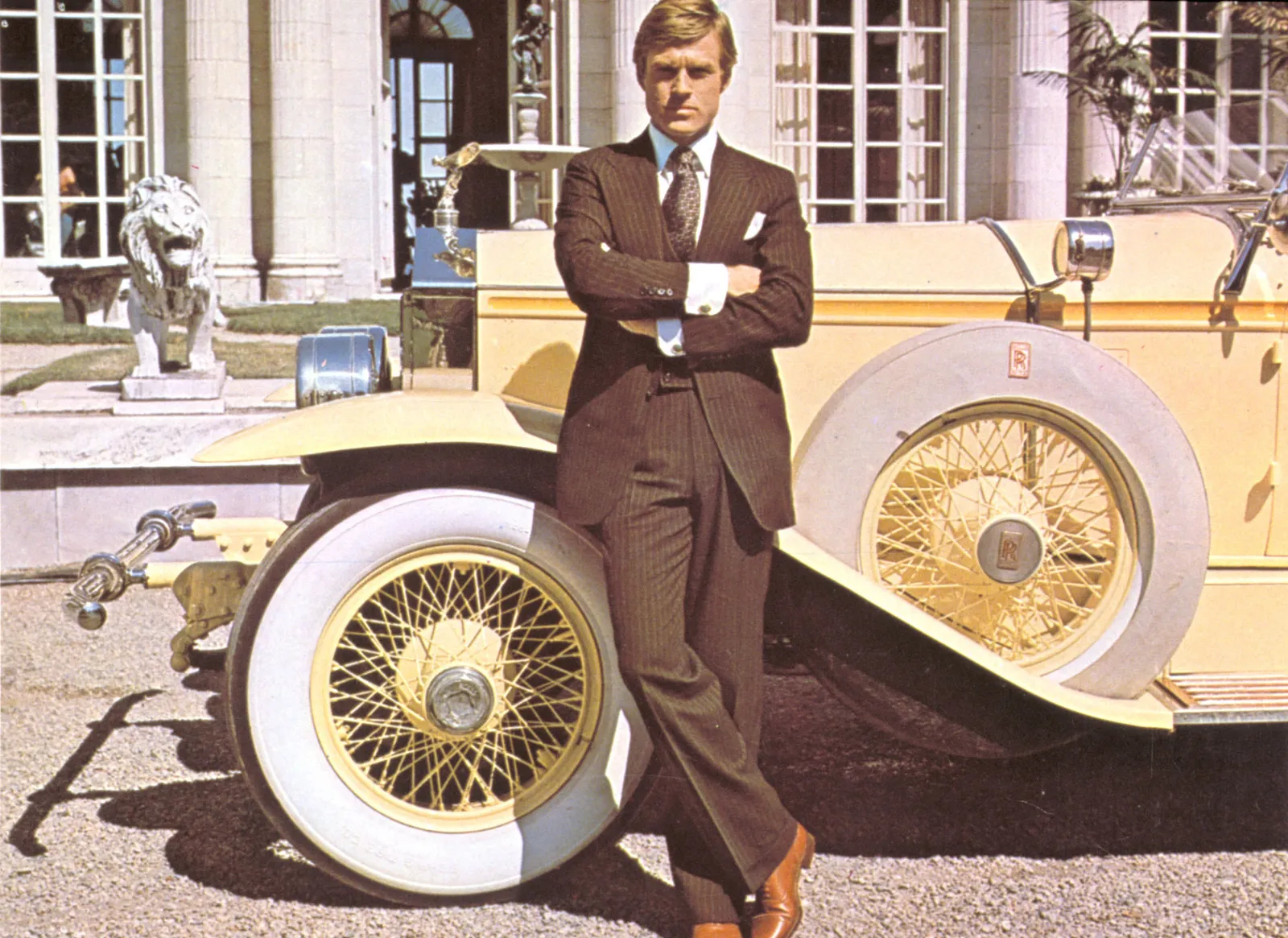

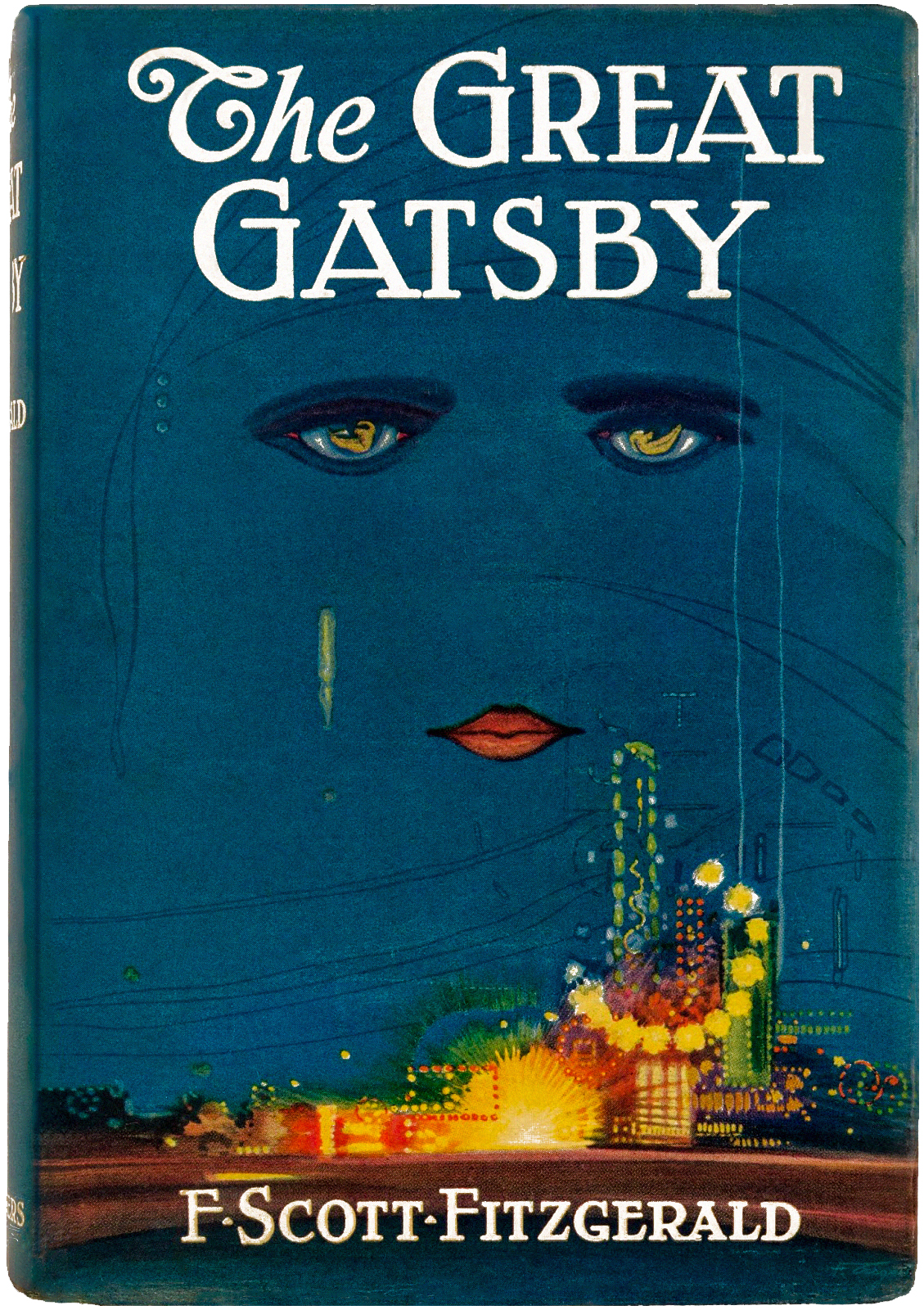

The Great Gatsby was an immediate success and then forgotten and then rediscovered. It was forgotten because the Jazz age was a, beautiful maybe, but still nearsighted dalliance. Fitzgerald was lumped in with all of the other out of date out of style gaucheness the book was mistaken as a celebration of. It was rediscovered because critics realized the book was like one of those sweetly scented break up notes that is written so beautifully that the dumped sod misreads it as a love letter and puts it with the other love notes unawares.

The Great Gatsby was a warning; and you can only hear the warning after the fall.

Perhaps half love letter and half kiss off, some part of Fitzgerald knew that his world was ending. The Jazz age was the parodos, or fun act of the ancient Greek tragedy where characters expound humorously against the chorus on the character faults that will undue them against the grinding unwinding of time.

Ancient Greece and Rome look the same in the periphery and quite different in focus. Greeks sought to be ideal through archetype where Romans sought reality through realism.

Greece, like F. Scott Fitzgerald, dealt in the realm of the anima – the passive, intuitive, and emotional aspects of the psyche. They were comfortable with beauty through vulnerability and had a poetic culture that celebrated poetic introspection. The Greeks were fascinated with the introspective world of the psyche, and their ability to express complex emotions and ideas through symbolic and mythological language. To them archetypes were like platonic forms, or perfect ideals, removed from time.

Ancient Greek Beauty

Rome, like Fitzgerald’s contemporary Ernest Hemingway, was more closely associated with the qualities of the animus – the masculine, assertive, and imperialistic, aspects of the psyche. Roman culture was characterized by its emphasis on law, order, and external appearances of military might. It gave rise to some of the most impressive feats of engineering, architecture, and political organization in the ancient world. The Romans were known for their practicality, their discipline, and their ability to translate ideas into concrete realities. To Rome the aspirational and ideological only mattered in hindsight.

Ancient Roman Beauty

To a Greek one noticed the archetype or one failed to. To a Roman on created the archetype. Humans made things real or we didn’t. Romans got credit for ideas in a way that Greeks didn’t. To a Greek we were glimpsing the inevitable realms of the possible. Time was cyclical. Ideas were external. You didn’t have ideas, they had you. For Romans a man came up with the ideas. This is an interesting dichotomy because both ideas are true but paradoxical ways of studying the psyche.

All of the early modernists engaged with this dialectic differently. Fitzgerald leaned Greek animistic, Hemingway leaned into the Roman Animus and other contemporaries like Gertrude Stein tried to bridge the divide. There was no way around as literature progressed.

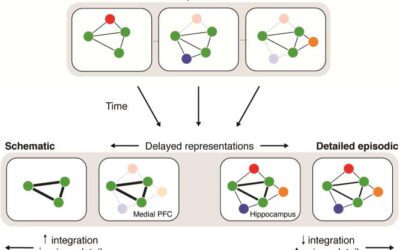

Greece and Rome were also deeply interconnected and mutually influential. Greek art, literature, and philosophy had a profound impact on Roman culture, and many Romans saw themselves as the heirs and stewards of the Greek intellectual tradition. At the same time, Roman law, government, and military power provided a framework for the spread and preservation of Greek ideas throughout the Mediterranean world. We need both the anima and animus to be the whole self, effective at wrestling the present and possible together if we are to effectively act on the impending real.

The intuition of the anima can let us see the future through dreams of creativity and visions for the possible but the animus is what lets us bring our agency to bear on the present moment. It is easy to hide in either one but miss the both.

I read The Great Gatsby in high school and it was one of the few assigned readings I didn’t hate. I wanted to read Michael Crichton and classical mythology primary sources but the curriculum wanted me to slog through things like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Zora Neal Hurston. I enjoyed the points those authors made, criticizing puritanism, and celebrating African American folk culture respectively but I thought the stylism made reading them a slog. The Great Gatsby was simple and I have reflected on it over the course of my life.

In high-school I saw Hemingway and Fitzgerald as two halves of the same coin. Fitzgerald was the nostalgic, reflective anima to Hemingway’s masculine animus. Hemingway jumped headlong into the morphine promises of modernism. Fitzgerald seemed to reflect on modernity better because he was pulled begrudgingly into it while trying to look further and further back into the past and its inevitabilities of “progress”. Most of my friends were manly Hemingway’s comfortable in the logos of the accessible real, and I was a navel-gazing Fitzgerald who only felt comfortable cloaked in the mythos of intuitive spaces

In Jungian psychology, the concepts of anima and animus are crucial for understanding the inner world of the creative. The anima represents the feminine aspects within the male psyche, while the animus represents the masculine aspects within the female psyche. A healthy integration of these archetypes is essential for wholeness in the personal life behind the creative works. As a therapist I find those and other Jungian concepts usefully to understand why certain people gravitate naturally to things over the course of their life.

Fitzgerald’s work and life were dominated by his anima, which manifested in his nostalgic yearning for the past, his romantic idealization of women, and his sensitivity to the nuances of emotion and beauty. While these qualities fueled his artistic genius, they also left him vulnerable to depression, addiction, and a sense of alienation from the modern world. It was this alienation from modernism while writing as a modernist that gave Gatsby a timeless predictive quality Hemingway lacks. Ultimately he was able to predict the future as a creative but unable to adapt to it as a man.

Hemingway, on the other hand, embodied the over-identified animus – the archetypal masculine energy that values strength, independence, and action above all else. His writing celebrated the virtues of courage, stoicism, and physical prowess, and he cultivated a public image as a rugged adventurer and man of action. However, this one-sided embrace of the animus left Hemingway emotionally stunted, unable to connect deeply with others or to find peace within himself. Hemingway is all bombastic adventure and when the adventure is over there was little left.

One of their other contemporaries, Gertrude Stein seems to have been able to achieve a kind of dynamic balance between her masculine and feminine qualities. This is not to say that she was free from all psychological conflicts or blind spots, but rather that she was able to channel her energies into her work and her relationships in a way that was largely generative, sustainable and life-affirming. Stein’s life and work could be seen as an example of the transformative power of integrating the anima and animus within the psyche.

Fitzgerald’s own insecurities and traumas contributed significantly to his anima-dominated psyche and artistic worldview. Fitzgerald remained haunted throughout his life. Had he lived long enough to encounter Jung’s work, Fitzgerald would have likely been profoundly influenced by it. Jay Gatsby seems to be the Jungian archetype of the “puer aeternus” (eternal boy) frozen by an impossible to attain object of desire and a refusal to grow up. A charming, appealing, affecting but ultimately failed visionary chasing red herrings. Fitzgerald himself seemed to go down the same path as other male Jungian’s, most notably, James Hillman and Robert Moore, failing to fully “ride the animus” and integrate their assertive energies to manifest changes in their personal lives. All were beautiful artists but not always beautiful men, especially in their end.

There seems to be a common thread in these anima over identified men – a childhood trauma that stifles self-expression, which paradoxically fosters a some what magical, intuitive, visionary ability to see the future. In adulthood, this ability makes one a profound artist, garnering success and a wide audience. However, the external validation and success do not heal the original, still screaming, wound. This disconnect between outer success and the failure of that success to balm the original inner pain that sparked the need for it is something that many artists and depth psychologists of this personality type struggle to reconcile from.

In high-school they told me The Great Gatsby was the greatest novel ever written and expected me to believe them.

They also told me that getting straight A’s meant you were smart, that the hardest working got the highest paid, and that all they really wanted me to do was think for myself. All were clearly lies a sophistic system thought I was better off if I believed.

Obviously I had to find out later, pushing 40, that the book was on to something great.

Or, maybe you have to see the rise and fall of celebrity and missiles and trends and less obvious lies in your life before you start to get the book as its own second act.

Saying The Great Gatsby is a good book is like talking about how the Beatles were a great band or the Grand Canyon is big. It’s kind of done to death, and it’s even silly to say out loud to someone. Everyone had to read it in high school. To say it is your favorite book instantly makes others wonder if you have read another book that you didn’t have to read freshman year. Oh, Hamlet is your other “favorite” book? Thinks the person who knows you have skimmed two books in your life and the test.

How do you get the prescience of an extremely simple story at 16? How was anyone supposed to in 1925?

The Great Gatsby is, perhaps by accident, not really about what it is about. The Great Gatsby is a worm’s eye view of the universe that reminds us that our humanity itself IS a worm’s eye view of the universe and that our worms eye view on it and each other is what keeps us sane. Sane and the gears of the spectacle of culture and grinding along out of psychic neccesity.

We are a myopic species stuck in our own stories and others’ stories, but not on our own terms. We are caught between improv and archetype but never free of either. Both subject to the human inevitable indelible programmed narrative and object of our own make-believe individual freedom from it.

The Great Gatsby is a book that you read in high school because you could hand it to almost anyone. It has done numbers historically and currently as a work in translation. It holds up some kind of truth to students in places like Iran who have no experience with prohibition, with alcohol, with American culture as insiders. Yet they still feel something relevant connecting them to the real.

It works because the characters are kind of stupid. It works because the moral of the story is, on its face, (and just like high school) kind of wrong. The Great Gatsby did see the future; it just didn’t know what it saw. I write about intuition quite a bit on our blog, and the thing that I think makes art interesting is when the work of art sees past the knowledge of the artist making the work.

The Great Gatsby gets a lot of credit for being prophetic in that it saw the Great Depression as the end of the Jazz age, but it did so because Fitzgerald was seeing his own end. Fitzgerald was severely alcoholic during prohibition, delaying his own deadlines for the novel that almost didn’t get there with excuses to his publishers. What would he become after the Volstead Act was repealed? What would the country become after the economic bender that the upper class threw for itself in front of masses that were starving?

The power of the novel is when it knows that empires rise and fall. It’s when it knows that the valley of ashes is watching your yellow car speed by with dull sad eyes. It’s power is in knowing the feeling that when you get what you want, you don’t really deserve it, or maybe it doesn’t deserve you. Maybe it implies that time is something that we use, tick by tock, as a proxy for meaning because we fundamentally “fumble with clocks” like Gatsby and can’t understand time.

We need our history and our idolatry of the past to make meaning, but when the lens for our meaning-making remains fixed, the world becomes a pedestal to dark gods demanding the worship of the past at the expense of the future. As a man or a nation, we are bound to hit someone if we look in the rearview mirror to long.

The green light on the dock is a symbol that we mistake for the real thing and “take the long walk of the short dock”. With this dishonest relationship to time, we all become a Gatsby or a Tom. I am not sure which is worse. We either lack all ambition and live to keep up appearances, or we have so much ambition that we become the lie.

The “beautiful shirts” are just a glittering, stupid, trendy identity that we nationally put on every couple of years to forget that we’re about to sink into another depression. Skinny ties are out and gunmetal is in! makes us never have to look at the other side of ourselves or our empire.

The past gives us meaning and identity even as it slowly destroys us and robs us of those things. We are forced to use it as a reference point even though we know this relationship between us and it is doomed. We cannot stop the need for the next recession in this society any more than we cannot stop the need for the next drawer of trendy clothes.

The American Dream is a kind of nightmare, but it is still a dream because it keeps us sleeping through the nightmare we are in. Realization of lost purpose, regret and nostalgia, superficiality, emotional turmoil, or tone deaf foreshadowing are not things you need to look at when movies and wars are inventing such beautiful coverings for our imperial core and rent seeking economy. Why then do we cry? Wake up the organist, we are getting bored.

In The Great Gatsby, like in a Dickens novel, the plot is the archetype, and that necessitates a lot of conveniences. That might seem like a point of criticism, but it is also very human. Perhaps these truths become tropes are not faults of the plot or its contrivances but reasons for humanity, namely humans in America, to introspect.

As individuals or as a society, we turn our insecurity into some amazing and impossible outcome, and then we, like Gatsby, do that to compensate for what we refuse to accept, what we refuse to change about who we are or where we come from. Jay Gatsby is myopic, but he is too naive to be a narcissist. He is just sort of a dream of himself he forgot he was dreaming.

Nothing in Fitzgerald’s prose leans into The Great Gatsby being directly interpreted as a dream, but it is one possible interpretation that the novel is a sort of collective dream.

There is a Tom Buchanan in all of us also. Someone who would burn the world down just because we can’t have the lie that we want others to believe about us anymore. He is a refusal to accept the reasonable limitations that might have prevented the Great depression. If we can’t have the whole world, we will blow the whole world up! That is another tension (still unresolved) that The Great Gatsby saw coming for humanity.

The two forces of the lie and the dream are the things that make the boom and bust cycle of recession and surplus that have sustained America, sustain the lie in the individual and the society. but shhhhhhh….. it’s a dream not a lie!? Just like highschool the powers that be think that you are better off if you believe it.

Greece and Rome are relevant details to this reflection on a novel because neither one would have really mattered to history without the other half. Greece invented the culture and religious structure and Rome became the megaphone to amplify expansion of that culture. We study them as highschool students but we don’t want to see those distinctions even now. The predictive element in Fitzgerald made him live in a timeless present. His assumptions were at worst Platonic archetypes where all characters expressed endless inevitable cycles. At worst his characters were, Aristotelian ideal of knowledge; where ideas had characters, so characters could not have ideas.

Hemingway lived in a Roman, timeless present. Awareness of cycles of historical and social forces were not important. Maybe you identify with his archetypes and maybe not. He could not see through them. America when it needs to do advertising for a new product, movie or war will always side with Hemingway. I guess The Old Man and The Sea always feels important, to the individual, but it lacks relevance to the pathos and later deimos that society needs to really introspect well.

God is still a broken-down billboard, and only the stupid or the insane in America can recognize God for what he is. If God is happy with what he sees, we clearly are to distracted to notice Him. If god is unhappy, then he does not approve of my America, so he must not be really be God. This is the double bind that the eyes of T.J. Eckleburg, long out of business, put us in. Love me, and you must not be infallible; dislike me, and you must be wrong.

Fitzgerald ended his novel, but not his life, on the right note. Listen up creatives.

And so we beat on, boats against the current. Ceaselessly borne back into the past.

How do you end yours? How do you live it. You read it at 16 but how old are you now?

The narrator, Nick Carraway, is a perfect observer because he is hopelessly naive, knowing nothing about human life or experience. He learns all of it in the course of a few days from the terrible follies of the gods of his world – the complete pantheon of all the most powerful forces of the ’20s, the real, the now.

The traditional historic “blue cover” of The Great Gatsby juxtaposes the face of a ’20s flapper with the skyline of a city lit for celebration. The flapper’s face is studded with the traditional burlesque Cleopatra makeup that already juxtaposes a beauty mark with a teardrop. In the cover, the rising celebration of a firework becomes a teardrop falling. Is up and down forever really the same direction?, the book asks you before you open it. The Wall Street Journal tells you that same thing today in more words.

Fitzgerald never found a way to see past himself, even when he wrote those truths in his fiction. He ended his career in Hollywood, helping better screenwriters by coasting on his reputation from the book that became a meteoric firework. In the end, he became a cautionary tale, a reminder that even the most gifted among us are not immune to the ravages of trauma and addiction masquerading as intuition and artistry and the weight of unfulfilled dreams. What does Nick do with his when the book ends in the Autumn of 22? Did he make it out of the Autumn Summer cycle of New York? Do we?

Summary of Key Points for SEO purposes:

- The Great Gatsby speaks to both the sparkle of spectacle and the timeless inevitable reality it distracts us from. It was initially successful, then forgotten, and later rediscovered as a prescient warning.

- The essay compares ancient Greek and Roman cultures to the anima and animus in Jungian psychology. It posits that F. Scott Fitzgerald embodied the anima while Ernest Hemingway embodied the animus. A healthy psyche requires integrating both.

- Fitzgerald’s own traumas and insecurities contributed to his anima-dominated psyche. His life and work, especially the character of Jay Gatsby, seem to align with the Jungian archetype of the “puer aeternus” (eternal boy).

- The essay argues The Great Gatsby is prophetic in foreseeing the end of the Jazz Age and the coming Great Depression, even if Fitzgerald didn’t fully comprehend the implications of his own novel.

- The novel’s enduring appeal lies in its simple yet profound truths about the human condition – our need for meaning from the past, the dangers of living in a dream or lie, the inevitable boom and bust cycles of individuals and societies.

- The essay suggests The Great Gatsby can be interpreted as a collective dream, with Jay Gatsby representing naive ambition and Tom Buchanan representing entitled destruction.

- Ultimately, Fitzgerald became a cautionary tale, showing that even the most gifted are not immune to unfulfilled dreams and inner demons. The novel asks if we can break free of the cycles of our pasts.

- The eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg on the billboard are interpreted as a symbol of a broken-down God, whom only the stupid or insane in America can recognize for what he truly is. The essay suggests that if God is happy with what he sees, people are too distracted to notice Him, and if God is unhappy, then He must not approve of America, and therefore cannot really be God. This creates a double bind for the characters and readers, forcing them to either accept a fallible God or reject a disapproving one.

- The American Dream is portrayed as a nightmare that keeps people asleep, preventing them from confronting the harsh realities of their lives and society. The essay argues that the need for the next economic recession is as inevitable as the need for the next trendy fashion.

- The essay points out that the plot of The Great Gatsby relies on archetypes and conveniences, which might seem like a flaw but actually reflects the human tendency to seek meaning in familiar patterns and narratives.

- The eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg on the billboard are interpreted as a symbol of a seemingly absent or indifferent God, who either approves of the characters’ actions or is powerless to intervene. This creates a double bind for the characters and readers alike.

- The essay emphasizes the importance of the novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway, as a naive observer who learns about the complexities and tragedies of life through his encounters with the other characters. His journey mirrors the reader’s own process of disillusionment and realization.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jungian Thought to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

0 Comments