What Happens in Iphigenia in Tauris?

Euripides’ Iphigenia in Tauris is a complex and profound exploration of the themes of exile, identity, the relationship between the civilized and the barbaric, and the healing power of reconciliation. Through the story of Iphigenia, the maiden who was saved from sacrifice and now serves as a priestess in a foreign land, the play illuminates the archetypal journey of the soul and the transformative potential of the encounter with the unknown.

Summary of Iphigenia in Tauris

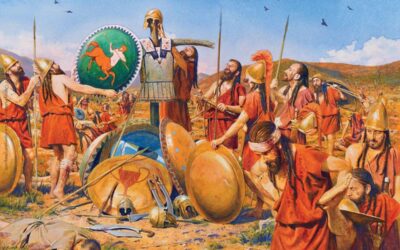

The play opens with Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon, serving as a priestess in the temple of Artemis in Tauris, a barbarian land. Years before, she had been saved by Artemis from being sacrificed by her father and brought to Tauris, where it is now her duty to ritually sacrifice any foreigners who come to the land.

Iphigenia’s brother Orestes, tormented by the Furies for matricide, arrives in Tauris with his friend Pylades, seeking to steal the statue of Artemis and thus free himself from the curse. They are captured and brought to Iphigenia to be prepared for sacrifice.

In a scene of recognition and reunion, Iphigenia and Orestes realize each other’s identities. They plan an escape, with Iphigenia agreeing to help Orestes steal the statue. Through a series of deceptions and confrontations, they manage to flee, taking the statue with them. The goddess Athena appears, sanctioning their actions and decreeing that Iphigenia will become a priestess in a new temple in Attica.

Archetypal Figures in Iphigenia in Tauris

Iphigenia: The Exiled Maiden

Iphigenia embodies the archetype of the Exiled Maiden – the young woman who is separated from her homeland and family, forced to make a new life in a foreign land.

Her position as a priestess in Tauris reflects the way in which the experience of exile can lead to a transformation of identity. Iphigenia has had to adapt to a new culture and take on a new role, one that involves the harsh duty of human sacrifice.

At the same time, Iphigenia’s inner conflict – her revulsion at her priestly duties and her longing for home – reflects the psychological split that can occur in the experience of exile. She is caught between two worlds, two identities, and must find a way to reconcile them.

In psychological terms, Iphigenia’s journey can be seen as a metaphor for the process of individuation – the development of a mature, integrated self. Her exile and her challenging role as a priestess represent the necessary confrontation with the unknown, the foreign aspects of the self that must be assimilated for wholeness to be achieved.

Orestes: The Wanderer and the Stranger

Orestes, Iphigenia’s brother, represents the archetype of the Wanderer and the Stranger. He is a figure in exile, driven from his homeland by the consequences of his own actions (the matricide of Clytemnestra).

Orestes’ arrival in Tauris and his encounter with Iphigenia reflect the way in which the wanderer’s journey can lead to unexpected discoveries and transformations. In confronting the foreign and the unknown, Orestes is also confronting the alien aspects of his own psyche, the guilt and trauma that have driven him into exile.

In psychological terms, Orestes’ journey can be seen as a parallel process of individuation – a necessary descent into the underworld of the psyche in order to achieve healing and wholeness. His reunion with Iphigenia and their joint theft of the statue represent the integration of the anima (the feminine aspect of the male psyche) and the reconciliation of the civilized and the barbaric within the self.

Athena: The Wise Goddess

Athena, who appears at the end of the play to sanction the actions of Iphigenia and Orestes, represents the archetype of the Wise Goddess – the divine feminine principle that guides and oversees the journey of the soul.

Athena’s intervention reflects the way in which the process of individuation is ultimately guided by a higher wisdom, a transcendent principle that reconciles opposites and brings order out of chaos. Her establishment of a new temple for Iphigenia in Attica represents the integration of the foreign and the familiar, the creation of a new psychic wholeness.

In psychological terms, Athena can be seen as a symbol of the Self – the regulating center of the psyche that guides the process of individuation. Her appearance at the end of the play suggests the ultimate goal of the psychic journey – the realization of a divine order and meaning that transcends the individual ego.

Themes and Psychological Insights

Exile and Identity

A central theme of Iphigenia in Tauris is the experience of exile and its impact on identity. Both Iphigenia and Orestes are figures in exile, separated from their homeland and forced to confront foreign cultures and ways of being.

For Iphigenia, exile has meant a transformation of identity – a taking on of a new role as a priestess in a barbaric land. Her inner conflict reflects the psychological challenge of integrating this new identity with her old sense of self, of finding a way to reconcile the foreign and the familiar.

For Orestes, exile is a consequence of his own actions, a manifestation of his psychological guilt and trauma. His wanderings reflect the restless search for redemption and wholeness, the need to confront and integrate the alien aspects of his own psyche.

In both cases, the experience of exile is ultimately transformative – a necessary stage in the journey of individuation. It is through the confrontation with the unknown, the assimilation of the foreign, that a new, more integrated sense of self can emerge.

The Civilized and the Barbaric

The play also explores the complex relationship between the civilized and the barbaric, the familiar and the foreign. Tauris, where Iphigenia serves as a priestess, is depicted as a barbaric land with cruel customs, in contrast to the civilized world of Greece.

Yet the play also suggests that the line between the civilized and the barbaric is not as clear as it might seem. Iphigenia’s own father, Agamemnon, was willing to sacrifice her for the sake of a military campaign. The matricide committed by Orestes, while driven by a sense of justice, is also a barbaric act.

In psychological terms, this tension between the civilized and the barbaric can be seen as a reflection of the relationship between the conscious and the unconscious mind. The unconscious, like the foreign land of Tauris, can seem threatening and alien to the conscious ego. Yet it is only by engaging with these unknown aspects of the psyche, by integrating the shadow, that true wholeness can be achieved.

The Power of Ritual and Sacrifice

Throughout the play, the theme of ritual and sacrifice is central. Iphigenia’s role as a priestess involves the ritual sacrifice of foreigners, a barbaric custom that she finds repellent yet must carry out.

The theft of the statue of Artemis, which is central to the plot, can also be seen as a kind of ritual – a necessary act of transgression that leads to a new order. Orestes’ own journey has been driven by the need to rid himself of the taint of his crime, a kind of psychological sacrifice.

In psychological terms, the theme of sacrifice can be seen as a metaphor for the necessary letting go of old identities and patterns that must occur in the process of growth and transformation. The ego must surrender its attachments, must allow aspects of itself to ‘die’, in order for a new, more integrated self to be born.

The Healing Power of Reconciliation

Ultimately, Iphigenia in Tauris is a story of reconciliation and healing. The reunion of Iphigenia and Orestes, their escape from Tauris with the statue of Artemis, and the establishment of a new temple in Attica all suggest a resolution of conflicts and a new psychic wholeness.

This reconciliation occurs on multiple levels – between brother and sister, between the civilized and the barbaric, between the conscious and the unconscious mind. It suggests the transformative power of the encounter with the other, the way in which engaging with the unknown can lead to a more integrated and whole sense of self.

In psychological terms, this process of reconciliation can be seen as the ultimate goal of the individuation journey – the achievement of a new balance and harmony within the psyche, the resolution of opposites in a higher synthesis.

Conclusion

Euripides’ Iphigenia in Tauris is a rich and multifaceted exploration of the archetypal journey of the soul, the process of individuation that leads to a new wholeness and integration of the self.

Through the figures of Iphigenia, Orestes, and Athena, and through the themes of exile, identity, the civilized and the barbaric, ritual and sacrifice, and the healing power of reconciliation, the play illuminates the complex and often challenging process of psychological growth and transformation.

At the same time, in its portrayal of the transformative power of the encounter with the unknown, the play offers a profound insight into the dynamics of the psyche and the potential for healing and renewal that lies within each of us.

Ultimately, Iphigenia in Tauris stands as a testament to the enduring power of myth and archetype to illuminate the depths of the human soul. It is a reminder of the universality of the journey of self-discovery, and of the profound wisdom and insight that can be found in the ancient stories that have shaped our collective imagination.

In this way, Iphigenia in Tauris is not just a masterpiece of ancient Greek drama, but a timeless guide to the mysteries of the psyche – a call to embrace the unknown, to reconcile the opposites within ourselves, and to find meaning and wholeness in the great adventure of life.

Read About Other Classical Greek Plays and Their Influence on Depth Psychology

Classical Literature

Iphigenia in Aulis

0 Comments