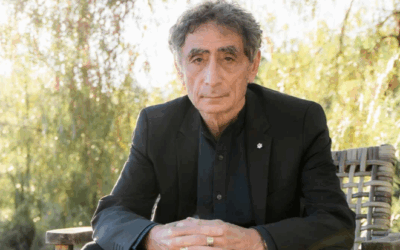

1. Who Was Erich Fromm?

Erich Fromm (1900-1980) was a renowned psychoanalyst, sociologist, and humanistic philosopher who made significant contributions to our understanding of the human condition in the modern world. Born in Frankfurt, Germany, Fromm was deeply influenced by the tumultuous events of the 20th century, including the rise of fascism, the Holocaust, and the Cold War. These experiences shaped his lifelong commitment to exploring the psychosocial roots of authoritarianism, alienation, and the pathologies of “normalcy” in contemporary societies.

Trained in sociology, psychology, and psychoanalysis, Fromm became one of the most prominent figures in the neo-Freudian movement of the mid-20th century. Along with colleagues like Karen Horney and Harry Stack Sullivan, he sought to revise and expand classical psychoanalytic theory, placing greater emphasis on the role of social, cultural, and economic factors in shaping personality development and psychological well-being.

Throughout his prolific career, Fromm published numerous influential books and articles that bridged the fields of psychology, sociology, politics, and spirituality. Works like Escape from Freedom (1941), The Sane Society (1955), The Art of Loving (1956), and To Have or To Be? (1976) offered penetrating analyses of the human condition under capitalism and the pathways to a more humane, democratic, and fulfilling way of life.

At the heart of Fromm’s thought was a deep concern for the dignity and growth of the individual in an increasingly mechanized, conformist, and alienating world. He saw the task of psychology not merely as the treatment of individual symptoms, but as the critique and transformation of sick societies that produced such symptoms in the first place. For Fromm, mental health was inseparable from the creation of social conditions conducive to human thriving – conditions that fostered love, reason, creativity, and solidarity over the dominant ethos of having, competition, and mindless consumerism.

In this sense, Fromm’s vision was profoundly humanistic and utopian, grounded in a faith in the human capacity for growth, love, and productive activity. Yet it was also tempered by a sober realism about the depths of human destructiveness and the powerful sociopolitical forces arrayed against individual and collective liberation. Fromm’s work thus stands as a clarion call for a psychology and politics of hope in an age of despair – a summons to the difficult yet necessary work of inner and outer transformation.

Main Ideas and Key Concepts

- Fromm’s work bridges psychoanalysis, sociology, and humanistic philosophy to offer a penetrating analysis of the human condition in the modern world.

- Central to Fromm’s thought is the concept of social character – the shared personality traits and orientations that emerge from the socioeconomic structure of a given society.

- Fromm argues that capitalism produces a marketing character oriented towards the commodification of the self and relationships, leading to widespread alienation, anxiety, and loss of authentic individuality.

- In contrast to Freud’s emphasis on the Oedipus complex and instinctual drives, Fromm stresses the existential needs for relatedness, transcendence, rootedness, identity, and meaning that shape human behavior and development.

- Fromm’s vision of the sane society is one that cultivates human growth and well-being by aligning the socioeconomic structure with these basic existential needs, fostering love, reason, creativity, and solidarity.

- Fromm critiques the pathologies of normalcy in contemporary society, including consumerism, bureaucratism, and the automation of thought and feeling, which produce a “consensual validation” of neurotic and self-alienated ways of being.

- For Fromm, authentic love – as care, responsibility, respect, and knowledge of the other – is the highest human achievement and the answer to the problem of existential isolation and anxiety.

- Fromm explores the roots of human destructiveness in both individual character and social conditions, examining how sadism, greed, narcissism, and necrophilia arise as distortions of the life-affirming drives for growth and aliveness.

- Fromm’s later work develops a humanistic spirituality based on the “having” vs. “being” modes of existence, calling for a shift from an ego-driven mode of acquisitiveness and control to one of openness, presence, and the productive realization of our human powers.

- Throughout his work, Fromm emphasizes the dialectical interplay of individual character and social structure, the possibilities for human growth and solidarity, and the need for a “humanistic psychoanalysis” attuned to the sociopolitical dimensions of psychological suffering and well-being.

2. Character and the Social Unconscious

Central to Fromm’s thought is the concept of social character – the shared constellation of personality traits, attitudes, and values that emerge from the socioeconomic structure of a given society. For Fromm, individual character is not solely the product of familial dynamics or instinctual drives, but is shaped in profound ways by the mode of production, social relations, and dominant ideologies of the larger culture.

In his landmark work Escape from Freedom (1941), Fromm traces the rise of the modern concept of the autonomous individual from the breakdown of medieval social bonds and hierarchies. While this liberation from traditional constraints opened up new possibilities for individual self-expression and achievement, Fromm argues, it also engendered profound feelings of isolation, powerlessness, and anxiety. Cut off from the security of fixed social roles and faced with the burden of constantly having to shape one’s own identity and path in life, the modern self is beset by a deep existential crisis.

For Fromm, the dominant response to this crisis in capitalist societies has been the emergence of a marketing character – a personality type oriented towards the commodification of the self and human relationships. In a culture where success is defined by one’s ability to “sell” oneself on the personality market, authenticity and intrinsic worth give way to the packaging of the self according to the demands of the market. The marketing character experiences life as an endless series of transactional encounters, viewing others as objects to be manipulated for personal gain rather than as ends in themselves.

This pervasive commodification of human life, Fromm argues, leads to a profound sense of alienation and self-estrangement. The individual feels disconnected from their own inner reality, as well as from genuine bonds of love and solidarity with others. Relationships take on a superficial, instrumental quality, while work becomes a meaningless chore rather than an expression of one’s creative powers. At the same time, the marketing orientation fosters a conformist mentality, as individuals seek to mold themselves according to the dominant social norms and expectations rather than developing their own unique individuality.

For Fromm, this alienated character structure is not merely a personal neurosis but a socially patterned pathology of normalcy. It reflects the distortions and contradictions of a society that subordinates human needs to the imperatives of the market and the state. The psychic suffering and emptiness experienced by individuals are thus symptomatic of a deeper malaise within the social body itself – a sickness that cannot be healed solely through individual therapy but requires a fundamental transformation of social relations and institutions.

In this sense, Fromm’s concept of social character points to the existence of a social unconscious – the repressed or disavowed dimensions of collective experience that shape individual psyches in ways that are not immediately apparent. Just as the personal unconscious contains the forgotten traumas and conflicts of an individual’s life history, the social unconscious holds the buried contradictions, injustices, and unfulfilled potentials of a given social order. Bringing these unconscious patterns to light and working through their implications thus becomes an essential task of a critical and emancipatory psychology.

3. The Sane Society and Humanistic Radicalism

If the marketing character and its attendant alienation reflect the pathologies of contemporary capitalist societies, what would a truly sane society look like? This is the central question that animates much of Fromm’s work, as he seeks to envision a social order that would foster human growth, creativity, and well-being rather than crippling and distorting the human spirit.

In The Sane Society (1955), Fromm argues that a healthy society is one that satisfies the basic existential needs of its members, allowing them to develop their full human potential. Drawing on his humanistic revision of psychoanalytic theory, Fromm identifies five such needs: relatedness (the need for love and belonging), transcendence (the need to create and embrace meaning beyond oneself), rootedness (the need for a sense of identity and place in the world), sense of identity (the need for individuality and self-realization), and a frame of orientation (the need for a coherent understanding of reality).

For Fromm, the alienation and neurosis so pervasive in modern societies stems from the systematic thwarting of these needs by the dominant institutions and values of capitalism. The marketing character, with its instrumentalization of human relationships and its worship of having over being, is fundamentally at odds with the growth and fulfillment of the whole person. Likewise, the bureaucratic rationality and conformist pressures of mass society stifle individuality and creativity, while the meaninglessness of alienated labor deprives people of a sense of purpose and connection to their own productive powers.

Against this backdrop, Fromm calls for a radical humanization of society – a transformation of economic, political, and cultural institutions to align them with the real needs of human thriving. This would entail a shift from the having mode to the being mode of existence, prioritizing the cultivation of our human capacities and the realization of life-affirming values over the endless pursuit of possession, status, and power.

At the heart of this vision is the idea of a humanistic democratic socialism – a society characterized by worker ownership and control of the means of production, decentralized participatory democracy, and a culture of solidarity, creative self-expression, and caring. Fromm argues that such a society would provide the conditions for the full development of human potential, allowing individuals to overcome alienation and find meaning through the free and conscious shaping of their collective life.

Fromm’s concept of the sane society is thus profoundly radical, in the sense of going to the roots of the social pathologies he diagnoses. Rather than seeking merely to ameliorate symptoms or adjust individuals to an unhealthy social order, he calls for a fundamental transformation of the structures and values that produce psychic suffering in the first place. This demands a humanistic radicalism that unites the psychological and the political, recognizing that the liberation of the individual is inseparable from the creation of a just and nurturing society.

At the same time, Fromm is clear that such a transformation cannot be imposed from above but must be the work of individuals and communities taking responsibility for their own lives and shaping their social world in the direction of greater freedom, creativity, and love. The role of the humanistic psychoanalyst, in this context, is not to prescribe a particular political program but to help people become aware of their own deepest needs and potentials, empowering them to become agents of personal and social change.

In this sense, Fromm’s vision of the sane society is not a static blueprint but an open-ended process of human self-creation – a continual striving towards forms of life that enable the full flowering of our species-being. It is a call to engage in the difficult yet exhilarating work of building a world that is truly worthy of our human potential, guided by the values of love, reason, and solidarity.

4. The Art of Loving and Human Solidarity

At the center of Fromm’s humanistic vision is the idea of love as the highest human achievement and the answer to the existential challenges of the modern age. In his classic work The Art of Loving (1956), Fromm argues that love is not primarily a feeling or sentiment, but an active power and capacity of the mature personality. Genuine love, for Fromm, is characterized by care, responsibility, respect, and knowledge – a stance of openness and affirmation towards the beloved that seeks to foster their growth and well-being.

Fromm distinguishes this mature form of love from various immature or illusory forms, such as narcissistic love (where the “beloved” is merely an extension or projection of one’s own ego), idolatrous love (where the other is worshipped as a godlike figure), or sentimental love (which remains at the level of superficial feeling without deeper commitment). True love, in contrast, is a deeply ethical and spiritual orientation, grounded in the recognition of the other as a unique and irreplaceable subject.

For Fromm, the capacity for love is not an innate given but something that must be actively cultivated and practiced. It requires the development of humility, courage, faith, and discipline – the willingness to confront one’s own limitations and anxieties, to take risks and embrace vulnerability, to commit oneself wholeheartedly to the well-being of another. In this sense, love is truly an art, demanding the same kind of dedication, skill, and patience as any other creative endeavor.

At the same time, Fromm emphasizes that the practice of love is not merely a private or interpersonal matter, but has profound social and political implications. In a society dominated by the marketing character and the ethos of competitive individualism, the values of care, solidarity, and mutual recognition are systematically undermined. The pursuit of self-interest and the instrumentalization of relationships make genuine love difficult if not impossible, leading to widespread feelings of isolation, mistrust, and existential anxiety.

In this context, the cultivation of love becomes a revolutionary act – a form of resistance against the dehumanizing tendencies of the status quo. By affirming the dignity and worth of each person, by seeking to create relationships based on mutuality and care rather than domination and exploitation, the lover prefigures a different kind of social order. Love thus becomes the basis for a new form of human solidarity – a sense of deep connection and shared destiny that transcends the narrow boundaries of ego and tribe.

For Fromm, this ethic of love and solidarity is the heart of a humanistic spirituality for the modern age. In a world that has largely lost touch with traditional religious frameworks and certainties, the direct experience of loving connection with others and with life itself becomes the wellspring of existential meaning and purpose. By embracing our common humanity and our radical interdependence, we can find the courage to face the challenges of our time with hope and resilience.

Fromm’s vision of love as a transformative social force is thus deeply utopian, in the best sense of the word. It dares to imagine a world in which the values of care, creativity, and communion shape our institutions and our daily lives – a world in which the full development of each is the condition for the full development of all. While recognizing the steep obstacles to such a transformation, Fromm insists on its necessity and possibility. The art of loving, he suggests, is the art of building a new human future – one grounded in the affirmation of life and the embrace of our shared potential for growth, joy, and solidarity.

5. The Dynamics of Human Destructiveness

While Fromm’s work is suffused with a profound faith in human possibility, he was also keenly aware of the depths of human destructiveness and the powerful forces that could distort and cripple the human spirit. Throughout his writings, Fromm seeks to understand the roots of violence, cruelty, and oppression, both in individual character structure and in the larger social conditions that shape personality development.

In works like The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973), Fromm challenges the Freudian view that aggression is an innate instinctual drive that must be repressed or sublimated for the sake of civilization. Instead, he argues that destructiveness arises primarily from the frustration of basic human needs and potentials – the thwarting of our inherent capacities for love, creativity, and productive activity. When these needs are chronically unmet, when individuals are subjected to conditions of oppression, injustice, and alienation, a characterological basis for violence and destructiveness can take hold.

Fromm identifies several key character orientations that embody this destructive potential. The sadistic character, for instance, seeks to gain a sense of power and control by dominating and humiliating others, deriving pleasure from their suffering and submission. The necrophilous character is attracted to death and decay, finding a perverse sense of vitality in the destruction of life. The narcissistic character is consumed by a grandiose sense of self-importance, viewing others merely as extensions or reflections of their own ego.

While these character types may manifest in extreme and pathological forms, Fromm argues that they are not simply individual aberrations but reflect deeper distortions within the social fabric. Sadistic and authoritarian tendencies, for instance, are often rooted in hierarchical and oppressive social structures that encourage the domination of the weak by the strong. Necrophilous orientations may arise in a culture that glorifies violence, militarism, and the objectification of nature and human life. Narcissistic traits are fostered by a society that places supreme value on individual achievement, competitiveness, and the commodification of the self.

At the same time, Fromm emphasizes that destructiveness is not an inevitable or fixed aspect of human nature, but the outcome of specific social and characterological conditions that can be transformed. By reshaping society in the direction of greater justice, compassion, and opportunities for human growth, the roots of violence and cruelty can be addressed and healed. This requires not only changes in economic and political structures, but a fundamental shift in values and character orientations – a move from the having mode to the being mode, from the pursuit of power and possession to the affirmation of life and love.

For Fromm, this transformative work is not only a social and political imperative, but an existential and spiritual one. In confronting and overcoming our destructive potential, we are challenged to realize our highest human possibilities – to become fully alive, creative, and loving beings. This demands a fearless reckoning with the shadow side of our individual and collective psyches, a willingness to face the pain and trauma that lie at the roots of our dysfunctions and conflicts.

Fromm’s analysis of human destructiveness thus points towards the need for a radical integration of psychology, politics, and spirituality. By bringing together insights from psychoanalysis, social theory, and the wisdom traditions of East and West, he seeks to illuminate the complex interplay of individual and societal factors that shape the human condition. In doing so, he challenges us to take responsibility for our own lives and for the larger web of relationships in which we are embedded – to become agents of personal and social transformation in the face of the existential threats of our time.

6. To Have or To Be?: The Great Alternative

In his later work, Fromm develops a comprehensive critique of the modern consumer society and its impact on human character and well-being. In To Have or To Be? (1976), he argues that the dominant orientation of capitalist culture is the having mode – a way of relating to the world that is based on possession, control, and the maximization of material wealth. This mode, Fromm suggests, leads to a profound sense of alienation, insecurity, and existential emptiness, as individuals seek to find meaning and fulfillment through the acquisition of ever more goods and status symbols.

Against this background, Fromm poses the great existential alternative of our time: the choice between having and being. The being mode, in contrast to the having mode, is characterized by aliveness, authenticity, and the full realization of our human powers. In the being mode, we relate to the world not as an object to be possessed or manipulated, but as a living reality to be experienced and engaged with creatively. We find meaning not in what we have, but in who we are and what we do – in the cultivation of our capacities for love, reason, imagination, and productive activity.

For Fromm, the shift from having to being represents a fundamental reorientation of human consciousness and society. It demands a break with the dominant values and institutions of capitalist modernity – the worship of progress, productivity, and unlimited growth; the reduction of human beings to interchangeable units of labor and consumption; the subordination of all aspects of life to the logic of the market. In their place, it calls for a new ethic of humanism and ecology, grounded in the recognition of the inherent worth and interconnectedness of all beings.

At the heart of this transformation is a re-visioning of the self and its relationship to the world. In the having mode, the self is experienced as an isolated ego, defined by its possessions and accomplishments, forever seeking to fill its inner emptiness through external acquisitions. In the being mode, the self is understood as a dynamic process of unfolding, a creative response to the call of life itself. It is a self that is fundamentally relational, finding fulfillment not in the assertion of its separateness but in the experience of deep connection and participation in the larger web of being.

Fromm’s vision of the being mode points towards a new kind of spirituality for the modern age – one that is grounded not in otherworldly escapism or dogmatic belief, but in the direct experience of the sacredness of life in all its forms. This spirituality is not a matter of adhering to fixed doctrines or practices, but of cultivating a way of being in the world that is open, present, and responsive to the mystery and wonder of existence. It is a spirituality that affirms the unity of the material and the spiritual, the personal and the political, the human and the more-than-human world.

For Fromm, the cultivation of this new consciousness is not only a personal journey but a social and political imperative. In a world facing ecological catastrophe, economic inequality, and the prospect of nuclear annihilation, the shift from having to being becomes a matter of survival for our species and for the planet as a whole. It demands a radical restructuring of our institutions and ways of life, from our systems of production and consumption to our forms of education, media, and governance.

At the same time, Fromm emphasizes that this transformation cannot be imposed from above, but must be the work of individuals and communities taking responsibility for their own lives and shaping their social reality in the direction of greater justice, sustainability, and human flourishing. The role of the psychoanalyst, the educator, the activist, in this context, is to help awaken people to their own deepest needs and potentials, to provide tools and spaces for self-reflection and social critique, to nurture the seeds of a new culture within the shell of the old.

Fromm’s later work thus stands as a powerful call to reimagine the human project in light of the great challenges and possibilities of our time. It invites us to question the dominant assumptions and values of our society, to reconnect with the deepest sources of meaning and purpose in our lives, and to take bold and compassionate action in the service of a more just and flourishing world. In doing so, it offers a vision of hope and transformation that remains as urgent and vital today as ever before.

7. Legacy and Relevance

Erich Fromm’s thought represents a unique and powerful synthesis of psychoanalytic, sociological, and humanistic perspectives, offering profound insights into the human condition in the modern world. His critiques of the pathologies of normalcy, his visions of human thriving and social transformation, and his explorations of love, creativity, and destructiveness continue to resonate with readers and to inspire new generations of thinkers and activists.

In the field of psychology, Fromm’s work helped to broaden the scope of psychoanalysis beyond the narrow confines of individual therapy, highlighting the ways in which mental health and illness are shaped by larger social and cultural forces. His emphasis on the social character and the pathologies of normalcy challenged the individualistic and conformist tendencies of mainstream psychology, paving the way for the development of more critical and socially engaged approaches such as liberation psychology and community psychology.

At the same time, Fromm’s humanistic vision of self-realization and his exploration of existential needs and values had a profound influence on the development of humanistic and existential psychology. Along with figures like Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May, Fromm helped to shift the focus of psychological inquiry from the mere adjustment of individuals to society towards the cultivation of human potential and the search for meaning and authenticity in life.

Beyond psychology, Fromm’s ideas have had a significant impact on social and political thought, particularly in the tradition of humanist socialism and critical theory. His critique of the alienation and dehumanization of modern capitalism, his vision of a sane society based on human needs and values, and his call for a radical humanization of social institutions have inspired generations of activists and theorists working for social justice and emancipation.

Fromm’s exploration of the roots of human destructiveness and his analysis of the authoritarian personality have also had a lasting influence on the study of political violence, racism, and authoritarianism. His insights into the psychological appeal of fascism and the mechanisms of escape from freedom continue to be relevant in understanding the rise of populist and authoritarian movements in our own time.

In the realm of spirituality and religion, Fromm’s work offers a powerful critique of dogmatic and otherworldly forms of religiosity, while pointing towards a humanistic spirituality grounded in the affirmation of life, love, and human solidarity. His engagement with Buddhist, Taoist, and mystical traditions, and his vision of a non-theistic religiosity centered on the experience of being and the realization of human potential, have helped to shape the development of new forms of spirituality and interfaith dialogue in the modern world.

Perhaps most importantly, Fromm’s thought continues to serve as a vital resource for all those seeking to understand and transform the world in the face of the great challenges of our time. In a global context marked by rising inequality, ecological devastation, and the resurgence of authoritarianism and fundamentalism, Fromm’s call for a radical humanism and a sane society based on love, reason, and human solidarity remains as urgent as ever.

As we grapple with the crises and opportunities of the 21st century, Fromm’s vision invites us to reimagine the human project from the ground up – to question the dominant values and institutions of our society, to cultivate new forms of consciousness and relationship, and to work towards a world in which all people can live with dignity, creativity, and joy. This is a vision that demands not only critical analysis and political action, but a deep transformation of the human heart – a renewed commitment to the practice of love, compassion, and solidarity in all dimensions of life.

In this sense, Fromm’s legacy is not just a matter of ideas and theories, but of a way of being in the world – a mode of radical humanism that seeks to awaken us to our deepest needs and potentials, and to inspire us to take responsibility for our shared future. As we navigate the challenges and possibilities of our time, may we draw courage and wisdom from his example, and may we find new ways to embody his vision of a truly human society in our own lives and communities.

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

John B Calhoun and Universe 25

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

0 Comments