What are the Archetypes of the Odyssey?

Odysseus as Trickster, Achilles as Warrior, Menelaus as King

Homer’s two epic poems, The Iliad and The Odyssey, present different archetypes of male heroes engaged in a cosmic battle that transcends the mortal realm. The Iliad explores the tension between the warrior archetype, embodied by Achilles, and the king archetype, represented by Menelaus. While Menelaus longs for the glory and honor of the battlefield, he is ultimately dependent on Achilles’ prowess as a warrior to achieve victory. This dynamic illustrates a fundamental truth about society – that the warrior is the driving force that moves it forward, even as other archetypes may seek to claim that power.

The Iliad also highlights how the gods themselves are deeply involved in this conflict, using mortals as pawns in a heavenly game of chess. This was a defining feature of Greek cosmology – the belief that earthly events were inextricable from the maneuverings of the gods. The war at Troy was not merely a clash of human armies, but a battle between divine factions, with men serving as proxies in a grander struggle. This metaphysical dimension imbues the story with a mythic resonance that goes beyond simple historical chronicle.

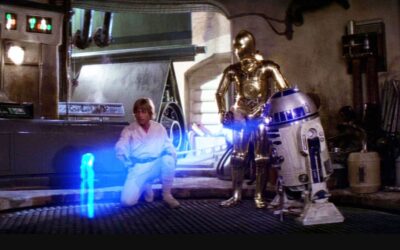

The Odyssey, in contrast, centers on Odysseus as the epitome of the trickster archetype. Odysseus relies on his cunning, adaptability and willingness to break the rules to navigate the treacherous journey home after the fall of Troy. His tale represents a different set of tensions – those inherent in the relationship between mortals and gods. The Olympians are all-powerful and often inscrutable in their motives, but they are not always fully in control of earthly outcomes. They can be outwitted, defied or evaded, at least temporarily, by a canny operator like Odysseus.

As a trickster, Odysseus is a master of manipulating perceptions, using disguise, deception and charm to influence both human and divine opponents. But while he can shape how others see him and events around him, he is not always in control of the fundamental forces underlying reality itself. His journey becomes a battle of wits between the trickster impulse for freedom and the unyielding dictates of the cosmos.

Through a Jungian lens, this paper will analyze how Odysseus embodies the trickster archetype in his quest to transcend limitations and move fluidly between realms. We will explore key passages that illustrate the paradoxical nature of the trickster and the ultimate impossibility of his goal to be truly free from the constraints of reality. In doing so, we will shed light on the complex relationship between mortal consciousness and the archetypal energies that shape our understanding of the world and our place within it.

The Trickster Archetype

In Jungian psychology, an archetype is a universal pattern of behavior that derives from the collective unconscious (Jung, 1969). The trickster is one such archetype, representing the cunning rebel who defies convention, breaks taboos, and undermines established structures and hierarchies. As Christen and Gill (2015) define it, “The trickster is a character in a story (god, goddess, spirit, human, or anthropomorphic animal) who exhibits a great degree of intellect or secret knowledge and uses it to play tricks or otherwise disobey normal rules and conventional behavior.”

The trickster archetype appears across many different cultures. Lewis Hyde describes the trickster as a “boundary-crosser” who “crosses both physical and social boundaries, disrupting normal life and then re-establishing it on a new basis” (Hyde, 1998, as cited in Guenther, 1999, p. 6). This boundary-crossing is central to the trickster’s nature and function.

In contrast to the warrior archetype exemplified by Achilles, who faces limitations head-on and strives valiantly to the point of death, the trickster archetype seeks to cleverly circumvent, deceive or simply ignore the rules that constrain him. The trickster longs for freedom from all that would limit or define him – mortality, social norms, gender roles, family obligations, the edicts of the gods themselves. He wants access to all realms and realities while remaining bound by none. This is an impossible, paradoxical goal that inevitably leads to complications, yet the trickster compulsively pursues it nonetheless.

It’s interesting to consider how different personality types may relate to these competing drives and fears. In the Myers-Briggs framework, intuitive-feeling types (NF) may be more unsettled by and averse to limitations, experiencing them as deeply unsettling “shadow” elements that threaten their sense of boundless potential (Myers & Myers, 1995). In contrast, sensory-thinking types (ST) may feel more comfortable with clear hierarchies, rules and roles that define their place in an ordered cosmos. The trickster impulse transcends type, but perhaps it is the NF types who feel it most acutely.

Odysseus as Trickster

Throughout The Odyssey, Odysseus displays his trickster nature through his use of clever stratagems, deception, disguise and rule-breaking to overcome the many obstacles in his way. After the fall of Troy, Odysseus sets out on a long and perilous journey home to Ithaca, but he defies the gods at multiple points along the way in his pursuit of his own kleos (glory).

Unlike Achilles in The Iliad, who must ultimately choose between “two sorts of destiny” – a glorious death at Troy and immortal fame, or a long peaceful life at home (Homer, Iliad 9.410-416) – Odysseus seeks to have it both ways. He wants the glory of being the hero of Troy, while also indulging his desires and returning to his wife and palace. As a trickster, he believes he can somehow “live in both worlds,” gaining honor through his exploits while also enjoying the comforts of home and hearth.

The text of The Odyssey reinforces this trickster characterization through its language. As Barnouw (2009) notes, “The text regularly uses terminology drawn from the semantic field of trickery, deceit, and cunning to describe Odysseus and his actions…such as dolos, mêtis, and pseudos. These words underscore Odysseus’ devious intelligence and ability to manipulate” (p. 141). Similarly, Newton (1997) points out that “Odysseus is often given epithets such as polymêtis (‘of many devices’) and polyainos (‘much-praised’)…these epithets advertise the hero’s slippery nature and emphasize the connection between his cunning and his kleos (‘glory’, ‘fame’)” (p. 273). The very language of the epic encodes Odysseus’ identity as a trickster hero.

Odysseus’ Hubris

However, this trickster capacity for holding opposites is both a strength and a weakness. It allows Odysseus to be remarkably adaptable and skillful in navigating challenges, but it also leads him into the temptation of hubris – the excessive pride that he can outsmart the gods themselves and transcend the very nature of reality.

Odysseus’ encounter with the cyclops Polyphemus is a prime example. Using his trademark cunning, Odysseus devises a plan to intoxicate the one-eyed giant and blind him, allowing the hero and his crew to escape the cave by clinging to the bellies of the monster’s sheep. However, as they sail away thinking themselves safe, Odysseus cannot resist a parting shot – he brashly boasts of his victory and even reveals his true name to Polyphemus (Homer, Odyssey 9.502-505). This proves to be a critical error, as Polyphemus is the son of Poseidon – Odysseus has directly challenged and angered one of the most powerful gods.

His hubris here sets in motion the wrath of Poseidon which will pursue Odysseus for the rest of his voyage home. The hero refuses to accept the very real limitations on human action – a mortal cannot mock the gods without consequence. Yet rather than compromise his pride or adapt his goals, Odysseus doubles down on his defiance, continuing to assert his own autonomy and ability to overcome divine will.

We see this hubris emerge again in the incident with Aeolus and the bag of winds. Aeolus gives Odysseus a bag containing all the winds, which could help him sail home to Ithaca. But Odysseus, in his arrogance, refuses to tell his men what is really in the bag, and in their curiosity they open it while he sleeps (Homer, Odyssey 10.28-55). The winds escape and blow them far off course, right back to where they started – a setback that could have been avoided if not for Odysseus’ excessive pride and poor judgment.

The trickster’s deep need to outfox the cosmos and be recognized for his exceptional cleverness ends up attracting the very limitations and negative attention he seeks to defy. In his book The Trickster and the Paranormal, George Hansen notes that tricksters “call into question the stability and reality of the foundations of the social world. And they are notorious breakers of taboos and violators of boundaries” (Hansen, 2001, p.36). This boundary-breaking is thrilling and powerful, but also dangerous and ultimately unsustainable.

The Paradox of the Trickster

This brings us to the central paradox that the trickster, and Odysseus himself, must grapple with. The trickster longs to be both inside and outside the game at the same time – he wants to be exempt from the rules of reality while still actively participating in the world and winning glory and acclaim. He craves the freedom to move between realms and forms at will, unbound by the limitations of the gods, nature or society.

But this is an impossible situation that cannot be maintained indefinitely. Joseph Campbell, in his seminal work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, described the hero’s journey as ultimately requiring a choice between the “left-hand path” of the rebel or the “right-hand path” of the dutiful acolyte (Campbell, 2008). The trickster, in contrast, “tries to do both at once and also none at all” – he insists on a third way of his own making, refusing to commit to either path.

In the short term, this mercurial flexibility allows Odysseus to navigate many challenges that would stymie a more rigid hero. But it also puts him fundamentally at odds with the way the cosmos works. He can bend the rules for a time through his own exceptional qualities, but no one, not even the gods, can break them entirely.

As Hyde (1998) puts it, the trickster is “the spirit of the doorway leading out, and of the crossroad at the edge of town” (p. 6-7) – always on the move, always seeking an escape or alternative, never content to be pinned down. He makes the world through his journeys and transgressions, as Radin (1956) says: “The Trickster is the embodiment of the life force in a world where the gods are captives of their own refined power… Only then does the Trickster become a world creator in his own right” (p. 185). But this world-shaping power of the trickster is ultimately constrained by forces greater than himself.

The allure of the trickster is that he seems to promise an escape from the human condition and all its uncomfortable limitations – a way to transcend mortality, to have one’s cake and eat it too, to never have to choose or sacrifice or face consequences. This is what makes the archetype so compelling, whether he appears as a mythological character, an advertising mascot, or a charismatic guru claiming to have the secret to a life without tradeoffs.

But in the end, Odysseus must make sacrifices and concessions to achieve his goals. He suffers for his hubris and finally learns to heed the guidance of Athena. He cannot simply outclever his fate, but must submit to powers and natural laws beyond his control, making peace with his own place in the order of things.

The Trickster in the Consulting Room

The trickster archetype often emerges in clinical work with individuals who feel constrained by societal expectations, personal limitations, or oppressive circumstances. As Jungian analyst John Beebe (2004) notes, the trickster can serve as an important compensatory function for the psyche, arising “in order to break up a stultifying situation and open up new possibilities” (p. 282). When rigid attitudes or external pressures threaten to overwhelm the personality, the trickster energy may be constellated as a way to assert autonomy, creativity and flexibility.

However, if the individual becomes overly identified with the trickster archetype, it can lead to a kind of psychological inflation and self-defeating behaviors. Jungian analyst James Hillman cautions that when the trickster is “enmeshed with the self,” it can result in “an overestimation of one’s cleverness and an underestimation of the risks and consequences of one’s actions” (Hillman, 1996, p. 144). The person may engage in increasingly reckless or manipulative behaviors, convinced of their own ability to outmaneuver any obstacle or repercussion.

This overidentification with the trickster can manifest as a kind of addictive or compulsive need to transgress boundaries and defy limitations just for the thrill of it. As Jungian analyst Bud Harris (2010) writes, “the shadow trickster can seduce us into believing that we can do anything, have anything, and be anything without suffering the natural consequences of our choices and actions” (p. 63). Like Odysseus taunting Polyphemus despite the obvious dangers, the individual may be more focused on demonstrating their own exceptional cleverness than on navigating challenges in a balanced way.

The Trickster’s Self-Defeating Tendencies

This trickster inflation often contains the seeds of its own undoing. By refusing to acknowledge real limitations, the individual sets themselves up for an inevitable fall when reality catches up to them. Odysseus’ journey is extended and his suffering increased precisely because of his hubris and excessive confidence in his ability to outwit the gods. As with the classical hero, the person in the grip of the trickster may find that their own worst enemy is themselves.

Joseph Campbell, in his book Pathways to Bliss, argues that the trickster’s antics ultimately aren’t a sustainable way of engaging with life: “The trickster is a mythological character who arises when the original harmony or unity of life has been lost and the world is broken into opposing camps – good and evil, truth and falsehood, stability and flux. The trickster lives amid this fracture, attempting to manipulate it to his advantage, but he never heals it” (Campbell, 2004, p. 210). The trickster’s methods can be useful for navigating a world of ambiguity and contradictions, but they cannot fundamentally resolve those contradictions.

Laurence Hillman, son of James Hillman and himself a Jungian analyst, suggests that the trickster’s self-defeating qualities stem from an underlying refusal to accept vulnerability and limitation. “The trickster fears being ordinary, fears being vulnerable, fears being just another human being – and these fears can push him into a never-ending cycle of boundary-crossing and risk-taking that ultimately leaves him exhausted and alone” (L. Hillman, 2020). Just as Odysseus resists returning to Ithaca and his identity as a husband and father, the trickster-possessed individual may find themselves running from the very things that could offer them genuine fulfillment and connection.

Integrating the Trickster

The task, then, is to find ways to harness the creative, disruptive energy of the trickster archetype without becoming overwhelmed by it. As Marie-Louise von Franz (1980) puts it, “The trickster impulse needs to be integrated into consciousness in a way that allows for flexibility and innovation while also respecting the need for stability and continuity” (p. 218). The individual must learn to tap into their inner trickster as a source of inspiration and resilience, but also temper its excesses with an awareness of real-world constraints and consequences.

This may involve cultivating a capacity for self-reflection and self-regulation, learning to pause before acting on tricksterish impulses. It also requires developing a stronger ego that can withstand the trickster’s provocations and enticements without being pulled entirely off-center. Techniques like active imagination, dream work, and creative play can provide safe containers for exploring trickster energy without being consumed by it.

Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate the trickster but to establish a conscious, collaborative relationship with it. When the ego can engage the trickster as an ally rather than being possessed by it, the individual gains access to a powerful source of creativity, adaptability and problem-solving capacity. The trickster’s boundary-crossing nature can be expressed through pursuits like entrepreneurship, artistic innovation, or social activism – anywhere there is a need for thinking outside the box and challenging the status quo.

But this positive expression of the trickster requires a hard-won wisdom and maturity. Like Odysseus at the end of his journey, the individual must accept that true heroism lies not in denying limitations but in acknowledging them and working effectively within their bounds. The trickster energy is harnessed in service of goals and values beyond itself, rather than being an end in itself.

In this way, the trickster archetype becomes a crucial part of the development of a robust, authentic self that can hold the tension of opposites and navigate life’s complexities with creativity and integrity. As the conscious personality learns to dance with the inner trickster rather than being led by it, a greater wholeness and freedom becomes possible. The individual becomes an artist of their own life, playing with the boundaries of the possible while also respecting the need for rootedness and responsibility.

Seen through this lens, Odysseus’ journey is not just an epic adventure but a metaphorical roadmap for this psycho-spiritual process. His trials and temptations reflect the challenges we all face in coming to terms with the trickster within. And his ultimate homecoming represents the hard-won integration that allows us to deploy our trickster capacities in life-affirming ways, while also embracing our place in the larger order of things. In learning to navigate the boundary between the worlds as Odysseus did, we discover the true power and purpose of the trickster archetype – as an essential part of our own heroic journey towards wholeness.

Legacy of The Trickster in the Meta Narrative and Psychology

By the end of The Odyssey, Odysseus does achieve a victory of sorts – he returns home to Ithaca, vanquishes the suitors vying for his wife’s hand, and reestablishes himself on the throne. His trickery and determination have allowed him to beat the odds in a battle against formidable human and divine opponents.

But this is a qualified victory, won at great cost and based on a recognition of real limits. Odysseus must accept his share of suffering, loss and hardship as the price of life, just as all mortals must. He cannot have both the perfect kleos of the immortal hero and the pleasures of the flesh, the comforts of home. He must ultimately choose, as Achilles did, what to sacrifice and what to embrace. Don’t forget too though that Odysseus is the one telling the story in the end of the book. He may be telling us a lie and the whole tale is another trick.

0 Comments