How Literally Did Ancient People Take Their Mythology?

The nature of gods and deities in ancient civilizations has long been a subject of fascination and debate. Did the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Norse, and followers of Vedic religions literally believe their gods to be anthropomorphic beings directly intervening in the mortal realm? Or were these mythological figures viewed more symbolically, as personified representations of natural forces, human virtues and vices, and the ineffable mysteries of the cosmos? As with most questions about the ancient world, the answer is complex and varies considerably between cultures, time periods, and social strata. Let’s embark on a journey through the mythic imagination of several major ancient cultures to untangle their beliefs about the reality of the divine.

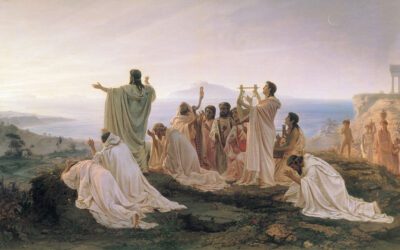

Homeric Gods and Philosophical Speculation in Ancient Greece and Rome

The gods of the Greek and Roman pantheons are perhaps the most familiar to contemporary pop culture, with names like Zeus, Athena, Jupiter, and Mars still echoing through literature, art, and even scientific nomenclature. But conceptions of these deities in the classical world itself was hardly a monolith.

The earliest literary evidence we have for ancient Greek religion comes from Homer’s epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey, likely composed around the 8th century BCE but reflecting an older mythic tradition. In these foundational works, the gods are depicted in strikingly anthropomorphic terms, with corporeal forms, individual personalities, and frequent impulsive interventions into human affairs.

In one memorable episode from the Iliad, the goddess Aphrodite physically shields her son Aeneas from harm on the battlefield, only to be wounded herself by the Greek hero Diomedes. The sky-god Zeus frequently shapes the course of the Trojan War with his rulings and manipulations, while his wife Hera schemes against him in favor of the Greeks. Mortal characters like Achilles and Odysseus have personal relationships with the gods as both benefactors and adversaries.

However, this larger-than-life literary depiction does not necessarily reflect the literal religious beliefs of ancient Greeks. Even within the Homeric epics, there are hints that the gods’ power operates on a different plane than direct physical action. When Athena appears to Achilles to counsel restraint in his quarrel with Agamemnon, the other Greeks witnessing the scene see nothing. The suggestion is that the gods can make themselves perceptible to humans selectively, perhaps more psychologically than materially.

As Greek philosophy developed in the classical period, thinkers began to question the mythology inherited from Homer and Hesiod. Xenophanes in the 6th century BCE famously criticized the all too human foibles and vices attributed to the Olympians, arguing that mortals merely fashion images of gods in their own likeness. Later influential philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle would develop much more abstract notions of divinity as ideals of goodness, sources of natural order, or an “unmoved mover” animating the cosmos.

For these sages, the gods as described in epic and popular religion were allegorical at best, and dangerously misleading at worst. In Plato’s ideal republic, he argues that tales of the gods feuding and misbehaving should be restricted, so as not to provide a negative moral example for citizens. The mythic tradition was still seen as a treasured cultural inheritance, but not as theological doctrine.

The same intellectual tensions carried over to the Roman world, where the Greek pantheon was adopted and adapted to suit new cultural mores. In Roman religion and literature, Jupiter, Venus, Mercury and company often take on a more stately, formal aspect than their Greek counterparts, reflecting Roman reverence for law, social order and imperial dignity. Mars, originally an agricultural deity, evolved into the consummate god of just war and military valor. Homeric myths of gods brawling on the battlefield did not align with the Roman self-conception.

Yet anthropomorphic visions of the gods still had a hold on the popular imagination, even as philosophical skepticism spread among the educated elite. In the 1st century BCE, Cicero’s dialogue De Natura Deorum (“On the Nature of the Gods”) staged a debate between several competing theological visions prevalent in his day. One character argues for the Epicurean view that the gods exist but are blissfully detached from the human sphere. Another contends for the Stoic position that the gods are immanent in nature and order the cosmos rationally. Cicero himself seems to favor a pragmatic view that upholding traditional rites and beliefs supports social stability, even if the particular details of the myths strain credulity.

What the Greek and Roman examples illustrate is that belief in the gods of myth was hardly uniform or universally literal, even in the ancient world. Ritual and storytelling kept anthropomorphic deities alive in the cultural consciousness, but engaged individuals formed their own philosophical and allegorical interpretations, creating a spectrum of literal to symbolic belief.

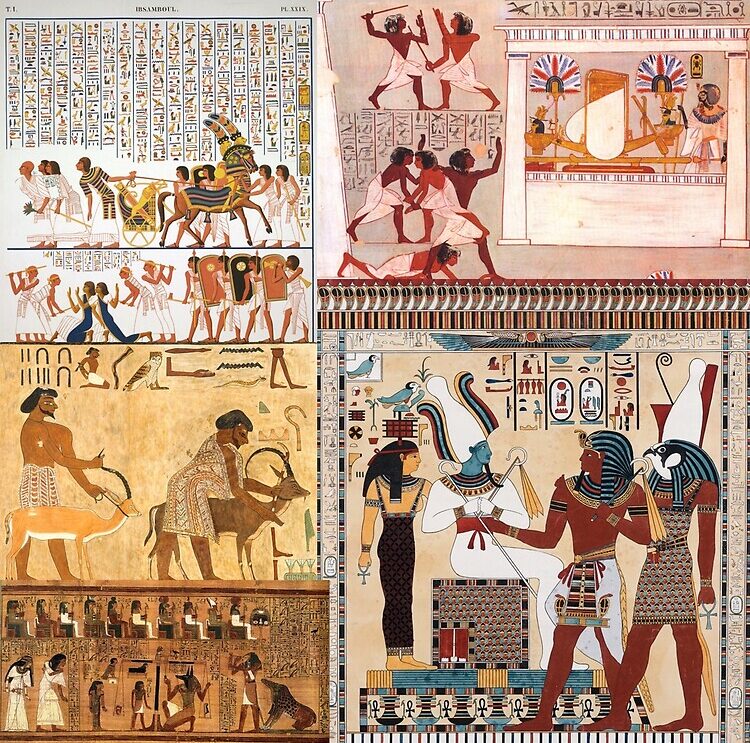

The Symbolic Bestiary of the Egyptian Pantheon

If the Greeks and Romans favored humanizing their gods, the ancient Egyptians took a more iconic, stylized approach. The Egyptian pantheon is filled with deities bearing animal features – jackal-headed Anubis, ibis-headed Thoth, falcon-headed Horus, cow-eared Hathor – to name just a few. These theriomorphic depictions have led to much misunderstanding over the centuries, with some outside observers assuming the Egyptians believed their gods to be literal animal-human hybrids.

However, Egyptologists largely concur that the animal aspects of the gods were intended as symbolic signifiers, not literal physical descriptions. Each animal was carefully chosen to represent a particular divine attribute or sphere of influence. Anubis’ jackal head, for instance, links him to the wild canines that prowled desert necropolises, reflecting his role as lord of mummification and guardian of the dead. Thoth’s ibis beak symbolizes his association with wisdom, magic, and the moon (as the ibis was thought to stand on one leg like the crescent moon). Horus’ falcon visage connects him to the soaring heights of kingship and the sun, as well as the keen-eyed discernment of a predatory bird.

These symbolic associations allowed for an instantly recognizable iconography, well suited to a culture that prized visual harmony, balance, and monumentality. When gods appear in purely human form in Egyptian art, they are often indistinguishable save for their headdresses and ceremonial paraphernalia. The animal attributes make each deity stand out as a unique entity, even as their overall forms remain familiar and approachable.

It’s telling that when the Greeks began to encounter and integrate Egyptian religion, they struggled to fully reconcile the Egyptians’ theriomorphic deities with their own norms of anthropomorphism. Herodotus could identify Anubis as “Hermes” based on his role as an underworld escort, but stumbles over whether he has the head of a dog or a jackal. Later attempts at Greco-Egyptian syncretism could downplay the animal aspects in favor of a wholly human appearance, as in the case of the hybrid god Serapis.

For the Egyptians themselves, the gods were at once transcendent and immanent, underlying the cycles of nature and the functions of society while also being accessible through festivals, temples, and personal devotion. The gods had births, marriages, rivalries and conflicts as told in myth, but they were not believed to be physically incarnating and acting on the mortal plane as in Greek epic. Instead, the myths express archetypal relationships and cosmic principles in vivid allegorical forms – the murder and resurrection of Osiris mirroring the fertilizing flood of the Nile, or the solar journey of Ra reflecting the eternal cycle of night and day, death and rebirth.

Animal symbolism was thus a way of signaling the numinous power of the gods, their simultaneous otherness and intimate presence in the natural world. It also reflects a uniquely Egyptian conception of animals as vessels of divine energy and as bridges between the earthly and the eternal. The Egyptians believed that all living creatures, not just humans, partook of the creative life force of the gods, and thus revering animals was an act of piety and a recognition of the underlying unity of existence.

The Mighty and the Monstrous in Norse Myth

Traveling northward from the Mediterranean world, we encounter the gods of the Norse or Germanic peoples of medieval Scandinavia and Iceland. These deities, preserved in the Prose and Poetic Eddas and later folkloric sources, present a strikingly different mythological ethos than that of the classical or Egyptian worlds.

The Norse gods, known as the Aesir and Vanir, are in many ways more earthy and fallible than their southern counterparts. They are not immortal or invulnerable, but rather gained their powers through the consumption of magical fruits and herbs. They face the constant threat of hostile giants and monsters, as well as an inescapable apocalyptic fate known as Ragnarok, the “Twilight of the Gods”.

This sense of struggle and doom imbues Norse myths with a melancholy and fatalistic atmosphere, perhaps reflecting the harsh realities of life in the far north. The gods are not distant Olympians but more akin to powerful, capricious chieftains, ruling over a precarious cosmic order. They feud among themselves, resort to deception and seduction to get their way, and sire monstrous offspring that turn against them.

Yet this apparent “primitiveness” belies a complex symbolic system at work in the Norse mythic imagination. The chief god Odin, for instance, is far more than a mere “sky father” in the vein of Zeus or Jupiter. He is a poet, a wanderer, a necromancer and above all a seeker of hidden wisdom, sacrificing his own eye and impaling himself on the world-tree Yggdrasil to attain occult knowledge. His is a shamanic power, won through ordeal and self-overcoming, that speaks to the value the Norse placed on secret lore and existential transformation.

Similarly, the hammer-wielding thunder god Thor is not just a brute divine enforcer but a hallower and protector of the community. His elemental battles with the giants symbolize not just the destructive power of the storm but the creative, fertilizing potential of the thunderbolt, the maintenance of cosmic equilibrium. His famous duel with the world serpent Jormungandr, prophesied to end in mutual destruction, encapsulates the Norse view of heroism as glorious struggle against insurmountable odds.

Other gods embody natural forces and social institutions, often with a darkly ambiguous edge. The fertility god Freyr presides over bountiful harvests and sacred kingship, but his liaison with the giantess Gerd hints at the danger and taboo associated with erotic passion. The trickster Loki, blood-brother of Odin, embodies the disruptive power of intellect and the necessary role of transgression in a cosmos built on law and order. Even the monsters and giants are not wholly evil but manifestations of the untamed potentiality of nature, the chaos that the gods must perpetually strive against.

In the Norse conception, then, the gods are not the source of an unchanging moral order but dynamic agents in a turbulent cosmos, their mode of being as important as their individual personifications. They model ways of confronting and creatively channeling the elemental forces that shape human life, offering templates for courage, wisdom, passion, and regeneration in the face of an uncertain fate.

While the extent to which the average Norse person literally believed in the Eddic myths is hard to gauge, archaeologists have uncovered ample evidence of cultic worship of the major deities, especially in the form of amulets and votive offerings. The myths likely resonated with the values and concerns of the Norse warrior-aristocracy, for whom themes of glory, honor, and fate were paramount. At the same time, the rich symbolism and psychological depth of the myths has continued to inspire reinterpretation and allegorical speculation down to the present day.

The Sacred and the Mundane in Hindu Theology

In the Vedic religious traditions of ancient India, we find perhaps the most sophisticated and philosophically developed conceptions of divinity in the ancient world. The earliest Vedic scriptures, dating back to the 2nd millennium BCE, reveal a pantheon of nature gods not unlike those of the Indo-European cultures to the west. Deities like Indra, lord of the storm and wielder of the thunderbolt, or Agni, the personified sacred fire, would be easily recognizable to the Greeks or Romans.

But as Vedic religion evolved into classical Hinduism in the first millennium BCE, theological speculation took a more abstract and monistic turn. The cryptic philosophy of the Upanishads, the gnostic and speculative texts that form the basis of Hindu philosophy, posits an ultimate identity between the individual soul (atman) and the impersonal cosmic principle of Brahman. The many gods of myth and cult are not denied but are seen as finite manifestations of this transcendent Reality.

A famous parable from the Chandogya Upanishad illustrates this perspective. The sage Uddalaka Aruni instructs his son Svetaketu to break open the fruit of a banyan tree and describe what he sees inside. “These seeds, almost infinitesimal,” the boy replies. The father then asks, “My son, that subtlest essence which you do not perceive there, of that very essence this great Banyan tree exists. Believe it, my son. That which is the subtlest essence, this whole world has that as its self. That is Reality. That is Atman. That art thou.”

In other words, the myriad forms of the phenomenal world, including the gods themselves, are merely the finite expressions of an infinite formless Essence, which is identical with the deepest core of the human self. This monistic vision would be elaborated by later philosophers like Shankara into the school of Advaita Vedanta, which regards all diversity and multiplicity as illusion (maya) overlaying the singular truth of Brahman.

At the same time, this ethereal monism exists in tension with the vibrant polytheism of popular Hinduism, with its teeming pantheon of gods, goddesses, demigods, and local spirits. For the average Hindu devotee, the gods are very much real presences, to be supplicated and adored through puja (worship), bhakti (devotion), and darshan (auspicious sight). The major deities like Vishnu, Shiva, and the Goddess take on multiple incarnations and manifestations, each with their own mythic narratives, iconographies, and cultic centers.

But even within this devotional multiplicity, there are strong tendencies toward theological integration and accommodation. The Smartha tradition, originating with the philosopher Adi Shankara in the 8th century CE, advocates the worship of five major deities (Vishnu, Shiva, Devi, Surya, and Ganesha) as different aspects of the ultimate Brahman. The notion is that these five provide different paths or approaches to the Divine, suitable for different temperaments and stages of spiritual development.

A popular teaching story illustrates this pluralistic attitude. A student approaches his guru and asks, “Master, you are always talking about the oneness of all things, but we worship so many gods. How many gods are there really?” In response, the guru transforms himself into the four-armed form of Vishnu and replies, “There is only one God.” Then he becomes the three-eyed Shiva, saying “There is only one God.” Then he becomes the ten-armed Durga, repeating “There is only one God.” Finally, he resumes his human form and explains, “It is all a matter of understanding. The wise see the One in the many, while the ignorant see only multiplicity and division.”

What this anecdote suggests is that for the Hindu mind, the literal truth of the gods is less important than their symbolic and pedagogical value. The gods are not so much fictive as multivalent, serving as focal points for spiritual reflection and moral cultivation. Their colorful mythologies encode profound philosophical and psychological truths, but are not necessarily expected to correspond to historical or scientific fact.

At the same time, the lived reality of Hindu devotion can belie this neat theological superstructure. For many practitioners, the gods are very much alive as personal beings, with whom one can have an intimate, emotionally charged relationship. The bhakti traditions in particular emphasize ecstatic love and surrender to the deity as a path to liberation, often eschewing philosophical abstraction in favor of direct experience of the divine beloved.

The Hindu perspective thus encompasses both the mythic and the mystic, the personal and the transpersonal dimensions of religious experience. The gods are at once cosmic principles and intimate presences, and their “reality” is not so much a matter of objective fact as subjective realization. In this sense, Hinduism anticipates the insights of modern psychology and comparative religion, which recognize the gods as archetypal symbols of the human psyche and perennial manifestations of the sacred.

The Spectrum of Ancient Belief

This brief survey of several major ancient religious traditions reveals that belief in the gods was hardly a simple or univocal phenomenon. In cultures as diverse as Greece, Rome, Egypt, Scandinavia, and India, we find a complex interplay of mythic storytelling, philosophical speculation, ritual practice, and personal devotion, each reflecting different facets of the divine.

The gods of epic and legend, with their all-too-human adventures and foibles, served as vivid representations of natural forces, social roles, and psychological truths. But they were not necessarily taken as literal beings by all segments of ancient society. Philosophers and mystics often sought to interpret the myths allegorically or derive more abstract theological principles from them. Ritual practice and cult worship could operate independently of mythic narrative, focusing more on the experiential reality of the sacred than on doctrinal coherence.

At the same time, we should be cautious about imposing modern notions of belief, with their emphasis on factual assent and intellectual coherence, onto ancient religious cultures. For many ancient peoples, the gods were simply a given, an inextricable part of the fabric of reality. Their existence was affirmed through the evidence of sense experience, the authority of tradition, and the pragmatic efficacy of cultic practice. Questioning or rationalizing the gods was the province of an intellectual elite, not the primary concern of the average devotee.

Moreover, the very concept of “belief” as a mental state distinct from ritual action or social conformity is a relatively modern development, shaped by centuries of Western Christian theology and Enlightenment philosophy. The ancients did not necessarily compartmentalize their religious lives into neat categories of “belief,” “practice,” and “ethics.” The gods were embedded in the totality of their lived experience, informing everything from the cycles of the seasons to the performance of social roles.

In this sense, the question of whether the ancients “really” believed in their gods may be somewhat misguided. Belief was not a simple binary proposition but a complex, multi-layered engagement with the numinous dimensions of reality. The gods could be at once literal and symbolic, personal and transcendent, immanent in nature and wholly other.

What mattered was not so much the objective truth of the gods as their subjective power to orient the individual and the community within a meaningful cosmic order. The myths, rituals, and images of the gods provided a framework for navigating the mysteries of life, death, and the universe. They gave shape to the ineffable, name to the unnameable, form to the formless.

In our own disenchanted age, it is easy to dismiss the gods of old as mere superstition or naive anthropomorphism. But to do so is to miss the enduring psychological and spiritual truths encoded in their stories and symbols. The gods may not be literal beings, but they remain potent realities of the human imagination, reflecting perennial aspects of the psyche and the cosmos.

By studying the rich and varied religious cultures of antiquity, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of human approaches to the sacred. We can move beyond simplistic notions of belief and unbelief, literalism and skepticism, to recognize the complex interplay of myth, ritual, philosophy, and experience that characterizes the religious quest. And we can perhaps recover some of the wonder and mystery that the ancients found in their encounter with the divine, however they may have conceived it.

In the end, the question of whether the gods were “real” to the ancients may be less important than what they can still teach us about the enduring human search for meaning, purpose, and transcendence. The gods may be long gone, but their stories and symbols live on, inviting us to contemplate the mysteries of the universe and our place within it. And in that contemplation, we may just catch a glimpse of the numinous reality that the ancients knew so well.

The expanded post delves deeper into the beliefs and mythologies of several major ancient cultures, including the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Norse, and followers of Vedic/Hindu traditions. It explores the complex interplay between literal and symbolic understandings of the gods, the role of philosophy and mysticism in reinterpreting myth, and the primacy of ritual practice and direct experience in ancient religion.

0 Comments