What are our psychological blindspots in mass and individual psychology?

“Maybe the only thing each of us can see is our own shadow. We are all like the blind man in the dark room looking for the black cat that isn’t there.”

– The Great Dictator, Charlie Chaplin

The Lacuna

There is a small region devoid of photoreceptors called the physiological blindspot or lacuna. Located where the optic nerve passes through the retina, this area literally cannot detect light. And yet, we don’t perceive a black void in our visual field. Our brain seamlessly fills in the blindspot based on surrounding visual information, editing it out of our conscious perception. Like an artful Photoshop edit, we are oblivious to this process.

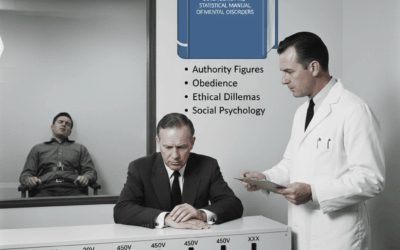

The Blindspot in Psychology

Just as we all have this blindspot in our visual field that goes unseen, there are also many blindspots in human psychology – both at the individual and societal level. The composition of our brains, the influence of evolutionary forces, and the imprint of culture create myriad lacunae in our cognition. Like the visual blindspot, we often fail to detect these gaps, with the mind automatically “filling them in” outside our awareness.

The early luminaries of psychology and philosophy were among the first to chart the landscape of the psyche and attempt to map these obscured regions. Each viewed the mind through the lens of their own experience, interpreting the source and significance of psychological blindspots quite differently.

Freud’s Blindspot: Repressed Sexuality

Sigmund Freud, in a rebellion against Victorian Era sexual repression, postulated that libidinal drive is the concealed source of all human motivation and behavior. For Freud, societal prudishness blinded us to the sexual foundation of the mind. He believed civilization necessitated the suppression of primal sexual and aggressive urges, which were then channeled into culturally acceptable outlets through the psychic processes of repression and sublimation. Dreams, jokes, works of art, and neurotic symptoms were all conceived as coded expressions of these stifled impulses. By making the unconscious conscious, Freud sought to expand the realm of rational choice and control.

Adler’s Blindspot: Inferiority and Compensation

Freud’s contemporary Alfred Adler, informed by his own physical limitations and the traumas of World War I veterans, contended that all psychological disturbance stems from overcompensation for feelings of inferiority. He saw a blindspot around our inherent need to strive for superiority and perfection. For Adler, the fundamental human drive was not libidinal but a will to power – an instinctive urge to overcome inadequacy and master both our inner world and outer environment. Psychological symptoms, in his view, arose from misguided attempts to gain significance and belonging, often by constructing grandiose fictions or retreating into self-protective but ultimately self-defeating behavior patterns.

Jung’s Blindspot: The Shadow

Carl Jung, Freud’s famous protege-turned-rival, developed the notion of the “shadow” to represent the unknown or unconscious aspects of the personality. He believed we all possess positive and negative attributes that the ego fails to recognize or identify with – the unrealized “golden shadow” of our highest potential and the disowned “shadow” of our darkest impulses. For Jung, integrating these exiled facets of the psyche was imperative for attaining wholeness or “individuation.” This meant embracing the shadow through dream analysis, active imagination, and other symbolic practices designed to reunite the conscious self with the unconscious psyche. Only by retrieving the projections we cast onto others and the world, Jung maintained, can we achieve genuine self-knowledge and relationship.

Later Jungian thinkers elaborated on Jung’s seminal ideas about the individual and collective unconscious. Erich Neumann traced the evolution of human consciousness through its mythic stages of development, which often involved fierce battles with the regressive pull of the archaic “Great Mother” and the inertia of the undifferentiated primal self. James Hillman re-visioned psychology as an imaginative undertaking, urging us to view the psyche as a polycentric multiplicity of mythical figures and archetypal forces, each with their own telos or purposive aim. Hillman saw neurosis and pathology not as disorders to be cured but as meaningful symptoms inviting deeper engagement with soul.

Marie-Louise von Franz further developed Jung’s method of amplification, which seeks to illuminate the personal significance of dreams and fantasies by connecting them to parallels in myth, religion, and folklore. For von Franz, attending to the objective psyche and its archetypal patterns was essential for freeing ourselves from the thrall of projection and expanding our capacity to experience symbolic meaning.

The Divided Brain: Blindspots in Consciousness

In the mid-20th century, neurologist Paul MacLean proposed the triune brain theory, depicting the brain as three neural strata from different evolutionary eras. He suggested that newer cognitive layers often operate in blindness to the influence of older, more primitive emotional and instinctive regions. The “reptilian complex” governs basic survival functions, the “paleomammalian” limbic system mediates social emotions, and the “neomammalian” neocortex enables abstract reasoning and language. For MacLean, schizophrenia and other disorders arose from the lack of integration between these semi-autonomous systems.

The divided mind model of consciousness pioneered by Roger Sperry, Michael Gazzaniga and others further elucidated how the verbal, rational left-brain interpreter confabulates explanations with limited insight into the workings of the mute right hemisphere. Split-brain studies, in which the corpus callosum connecting the two hemispheres was severed, demonstrated that each half has its own memories, skills, and characteristic modes of processing that are inaccessible to the other side. These findings problematized the notion of a unitary self and illuminated the ways the mind generates personal narratives to maintain a sense of continuity and control.

Blindspots in Culture: The Implicit Dimension

Anthropologists have also weighed in on humanity’s cognitive blindspots. Thinkers like Clifford Geertz and Victor Turner studied the implicit social agreements and symbolic cultural frameworks that pattern behavior and perception outside of awareness. According to Turner, cultures can only evolve by bringing the background assumptions of the societal blindspot into consciousness. Arnold van Gennep’s seminal work on rites of passage revealed a universal three-stage process of separation, liminality, and reintegration that structures identity changes at both the individual and collective level.

Lucien Lévy-Bruhl explored the ‘primitive mentality’ of indigenous peoples, which he saw as a mystical participation in nature lacking the subject-object distinction of modern rational thought. Claude Lévi-Strauss sought to uncover the deep structures of the human mind through the cross-cultural analysis of mythical narratives and kinship systems. For Lévi-Strauss, myths encoded the fundamental patterns and oppositions underlying all thought – the raw and the cooked, the sacred and the profane, the self and the other.

Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf proposed that our perception of reality is shaped by the grammatical structures and semantic categories of our native languages. What we see is both enabled and constrained by the linguistic framework we inherit. Similarly, Michel Foucault examined how epistemes — historically situated configurations of knowledge — circumscribe what can be thought in any given era. For Foucault, power and knowledge are inextricably intertwined, with discourse itself functioning as a site of social control.

Philosophy: Mapping the Blindspots of Thought

Various philosophers have also touched on the notion of perceptual and conceptual blindspots. Nietzsche’s perspectivism held that all knowledge is inextricably bound to viewpoint and that an objective “view from nowhere” is impossible. For Nietzsche, blindness to perspective – ignoring the embodied, interested nature of cognition – was the chief error of traditional philosophy. Objective truth was a fiction; the best we could hope for was an experimental multiplication of standpoints that enriched rather than eliminated interpretation.

For phenomenologists like Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the philosophical blindspot was the prereflective lifeworld that grounds and enables all theoretical inquiry. Husserl’s phenomenological reduction sought to suspend our ordinary assumptions and return “to the things themselves” as they present themselves to consciousness. Heidegger argued that detached theoretical reflection derived from a more primordial being-in-the-world, an involved practical coping obscured by the Cartesian quest for certainty. Merleau-Ponty emphasized the embodied nature of perception, arguing that we are not primarily thinking subjects but incarnate actors, geared into the world through our sensorimotor capacities.

In a more political vein, Karl Marx held that the dominant ideas and worldviews of any historical period are those of the ruling economic class. Our beliefs and values are shaped by material conditions and productive relations in ways that are largely invisible to us. Marx’s notion of ideology as false consciousness – a collective blindspot perpetuated by self-interested elites – was later taken up by the Frankfurt School in their critique of modern consumer capitalism. For thinkers like Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse, the “culture industry” worked to manipulate mass desires and perpetuate political passivity.

Walter Benjamin, in a similar spirit, detailed how ideological blindspots perpetuate unjust status quos until revolutionary acts expose them. In his famous analysis of mechanical reproduction, Benjamin argued that the technological proliferation of images was eroding the traditional aura and authority of art, creating possibilities for more collective forms of reception and progressive political appropriations. The Surrealists sought to unleash the emancipatory potential of the unconscious through practices of dream work, automatism, and juxtaposition that challenged bourgeois rationality and conformism.

The Existentialists focused on how we flee from our radical freedom into prefabricated social scripts and self-deceptions. For Jean-Paul Sartre, we are “condemned to be free,” burdened by an inescapable responsibility we are often loath to acknowledge. Authenticity meant confronting the groundlessness of our choices and projects without appeal to higher authorities or essences. Simone de Beauvoir applied existential insights to the situation of women, arguing that patriarchal society perpetuated the myth of feminine essence to keep women trapped in immanence. The endpoint of existentialism was a heroic lucidity about the human condition, a clear-sighted assumption of our freedom and finitude.

Later French theory further probed the blindspots of Western thought. Jacques Lacan’s “return to Freud” recast the unconscious as a language, a hidden trove of signifiers that perpetually subverts the ego’s sense-making. Jacques Derrida’s method of deconstruction exposed the binary oppositions and hidden hierarchies that structure philosophical texts. For Derrida, meaning is endlessly deferred in a play of traces and differences without origin or closure. Gilles Deleuze sought to overturn Platonism and its privileging of identity over difference, the Real over simulacra. Deleuze affirmed a “crowned anarchy” of free-flowing desire, a productive unconscious that resists Oedipal representation and the stasis of Being.

A Blindspot Model of Psychological Suffering

Drawing on these myriad influences, I believe psychological blindspots can be most concisely defined as emotional positions that we become unconsciously enmeshed with or avoidant of. We either see them as indispensable to our being or deny their existence entirely. But in truth, emotions are tools that sometimes serve us and sometimes hinder us. The goal of therapy and self-actualization is to embrace the full spectrum of affect. To pick up each emotion as needed and put it down when no longer useful – remaining attached to none.

In this view, depression arises from an overidentification with negative feeling states like despair and futility. We come to see them as permanent fixtures of the self rather than temporary visitors. Anxiety stems from an enmeshment with fear and dread, a blindspot that magnifies threat and underestimates resilience. Mania defends against underlying feelings of worthlessness and vulnerability by latching onto an inflated sense of possibility and invincibility. Personality disorders reflect rigid attachments to particular emotional stances and relational patterns that were once adaptive but have outlived their usefulness.

The path of healing, in my view, involves a progressive disidentification with these default feeling states and an openness to the full range of emotional experience. We learn to dis-embed from our blindspots, to recognize that we are not our pain or panic or euphoria. Mindfulness practices help us cultivate a spacious awareness that can contain contradictory impulses without judgement. In this way, we develop a more flexible sense of self, grounded in the expansive witness rather than the ever-shifting contents of consciousness.

What allows us to take up this metacognitive position is secure attachment — a internalized sense of safety and welcome that frees us to explore the heights and depths of the psyche. When we know there is someone who accepts and loves us unconditionally, we can risk exposing our blindspots without shame. In the therapeutic relationship, this secure base is gradually introjected, so that we can become a compassionate holding environment for ourselves. Healing is not a matter of eliminating pain but of expanding our capacity to bear it. By confronting our blind spots with courage and curiosity, we reclaim the lost territories of the self.

This integrative process is not a solo endeavor but a fundamentally relational one. Our blindspots are often sustained by the myriad ways we hide ourselves from each other, by our fear of having our shadow seen and rejected. The intersubjective field of therapy provides a crucial context for this unveiling, as patient and analyst negotiate an encounter with otherness. Analyst and analysand struggle to recognize and acknowledge their respective illusions and projections, to withdraw fantasies of omniscience and fusion. As they surrender their cherished images of self and other, a more authentic intimacy becomes possible.

Confronting the Blindspot, Expanding Awareness

While we can never fully escape our lacunae, we can commit to illuminating them through introspection, dream work, shadow boxing, cultural criticism, and the intersubjective process of dialogue and relationship. By striving to know ourselves and our society, peering into the blindspots that are an inescapable part of being human, we can expand the sphere of choice and freedom. And perhaps, by patching together our partial perspectives, we can begin to glimpse a greater truth.

In the stirring words of poet Adrienne Rich, “We can count on so few people to go that hard way with us.” The journey of expanded awareness is a lonely and uncertain one, with few reassuring landmarks. It takes tremendous fortitude to venture beyond the well-worn grooves of consensus reality and confront the unseen dimensions of existence. Yet for those with the courage to face the void, the rewards are profound – a vitality and connectedness that comes from embracing the full catastrophe of the human experience.

As finite beings, we are fated to see as through a glass darkly, forever bumping up against the limits of our understanding. But by bringing awareness to our blindspots – cultural, psychological, existential – we participate in the evolution of consciousness itself. We become active players in the millennial process of awakening, lightening the load of ignorance and illusion for ourselves and others. Though we cannot know the ultimate destination, we can find purpose and joy in the going.

“Son of man, You cannot say, or guess, for you know only a heap of broken images.”

– The Waste Land, T.S. Eliot

0 Comments