Why Are There So Many Modalities of Psychotherapy?

The history of psychotherapy is a tumultuous one, marked by heated debates, acrimonious splits, and competing claims to truth. From its origins in Freudian psychoanalysis to the present-day landscape of integrative approaches, the field has been shaped by a succession of theoretical and clinical revolutions, each building on and reacting against what came before.

Freud and the Psychoanalytic Diaspora

The first great schism in the history of psychotherapy occurred within the ranks of Freudian psychoanalysis itself. While Sigmund Freud’s ideas about the unconscious, repression, and the structure of the psyche revolutionized thinking about the mind and behavior, his dogmatic insistence on the primacy of sexual drives and the Oedipus complex alienated many of his most gifted followers.

Alfred Adler, an early collaborator of Freud’s, broke with his mentor to establish Individual Psychology, which emphasized the importance of social context and “striving for superiority” in shaping personality. Adler saw human beings as fundamentally purposive, goal-directed creatures and argued that much psychological distress stemmed from feelings of inferiority and a lack of social interest. He developed concepts like the “inferiority complex,” “overcompensation,” and “style of life” that remain influential to this day.

An even more consequential split occurred with Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist whom Freud had anointed as his “crown prince” and intellectual heir. Jung challenged Freud’s focus on sexuality and childhood trauma, arguing instead for a view of the psyche as a self-regulating system with an innate drive towards wholeness and individuation.

Jung’s theory of archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the process of individuation reframed psychoanalysis as a modern continuation of perennial wisdom traditions, a move that sparked accusations of mysticism and anti-Semitism from Freud. Their bitter rupture divided the analytic community and marked the first great theoretical divergence in the field.

Other significant figures in the early psychoanalytic movement who ultimately rejected Freudian orthodoxy include:

- Otto Rank, who developed an existentially-informed “will therapy” emphasizing separation anxiety and the creative impulse

- Sandor Ferenczi, who pioneered a more empathic, relationally-attuned approach and challenged Freud’s ideas about the therapist’s neutrality

- Karen Horney, who critiqued Freud’s views on female psychology and emphasized the importance of cultural factors in neurosis

- Melanie Klein, who developed object relations theory and the technique of play therapy for children

- Anna Freud, Sigmund’s daughter, who also focused on child analysis and the development of the ego

The work of these post-Freudian analysts laid the groundwork for later developments in attachment theory, self psychology, and relational psychoanalysis.

The Behaviorist Rebellion

The rise of behaviorism in the early 20th century represented a radical break not only with psychoanalysis but with the very idea of inner mental life as a legitimate object of scientific study. Led by John B. Watson and later B.F. Skinner, the behaviorists argued that psychology should restrict itself to observable behavior, jettisoning concepts like consciousness, mental images, and the unconscious as unscientific vestiges of a pre-experimental age.

Inspired by Ivan Pavlov’s work on classical conditioning, Watson and his followers sought to establish psychology as a rigorously objective, empirically-based discipline on par with the natural sciences. They conducted experiments demonstrating how animal and human behavior could be shaped through principles of stimulus-response learning, and developed techniques for modifying problematic behaviors through operant conditioning.

While psychoanalysis remained ascendant in Europe, behaviorism quickly became the dominant force in American psychology, where its emphasis on prediction, control, and real-world application meshed well with the country’s pragmatic cultural ethos. Behaviorist ideas spread far beyond the confines of academia, influencing approaches to education, child-rearing, advertising, and social policy throughout much of the 20th century.

However, the behaviorist hegemony began to crack in the 1950s and 60s, as a new generation of thinkers challenged its reductionistic view of human nature and sought to reclaim the richness of subjective experience. The humanistic and existential movements, in particular, arose as a “third force” in psychology, rejecting both the determinism of psychoanalysis and the mechanistic stimulus-response model of behaviorism.

The Humanistic-Existential Insurgency

Humanistic psychology emerged in the mid-20th century as a reaction against the limitations of both Freudian theory and behaviorist technique. Led by figures like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, the humanists emphasized the inherent potential for growth, creativity, and self-actualization in every individual. They saw psychological distress not as a symptom of repressed conflicts or maladaptive conditioned responses, but as a block to the full realization of one’s authentic self.

Rogers pioneered client-centered therapy, a non-directive approach that placed the client’s own capacity for insight and self-determination at the heart of the change process. He argued that the core conditions for therapeutic growth were empathy, unconditional positive regard, and congruence or authenticity on the part of the therapist. By providing a safe, accepting space for self-exploration, the therapist could help clients reconnect with their inner valuing process and move towards greater openness, integration, and self-trust.

Maslow, in turn, developed a theory of human motivation that positioned self-actualization at the pinnacle of a hierarchy of needs, from basic physiological and safety needs to higher-order desires for love, belonging, and esteem. He studied high-functioning, self-actualizing individuals and argued that psychology should focus not just on treating pathology but on cultivating human potential and fostering “peak experiences” of joy, creativity, and transcendence.

Existential therapy, which arose in parallel with humanistic psychology, drew on the philosophies of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Sartre to grapple with the fundamental dilemmas of the human condition. Pioneering existential therapists like Rollo May, Irvin Yalom, and Viktor Frankl explored how confronting themes of freedom, responsibility, isolation, and mortality could catalyze a process of personal transformation and lead to a more authentic, purposeful mode of being.

While the humanistic-existential approach offered a much-needed corrective to the reductionism and determinism of psychoanalysis and behaviorism, it was often critiqued for its lack of scientific rigor, its focus on the individual at the expense of the social context, and its potential for fostering a kind of solipsistic self-absorption. Nonetheless, its emphasis on the primacy of subjective experience, the therapist-client relationship, and the human capacity for choice and meaning-making had a profound impact on the field, paving the way for the development of experiential, emotion-focused, and constructivist therapies.

Other significant figures associated with the humanistic-existential movement include:

- Fritz Perls, the founder of Gestalt therapy, which focuses on the here-and-now of immediate experience

- Virginia Satir, a pioneer of family therapy who emphasized communication, self-esteem, and personal growth

- J.L. Moreno, the creator of psychodrama and sociometry

- Eric Berne, who developed transactional analysis as a way of understanding interpersonal dynamics

The Cognitive Revolution

The cognitive revolution of the 1960s and 70s represented a seismic shift in the field, as psychologists began to study the mind as an information-processing system and to develop interventions aimed at modifying dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs.

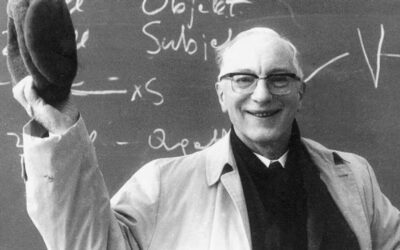

Albert Ellis was a key figure in this movement, pioneering Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) as a way of helping clients identify and challenge their irrational beliefs. Ellis argued that emotional disturbance was largely the result of self-defeating cognitions, and that by learning to dispute these thoughts, individuals could achieve greater emotional freedom and self-acceptance.

Aaron Beck, meanwhile, developed cognitive therapy as a short-term, structured approach to treating depression and anxiety. Like Ellis, Beck emphasized the role of maladaptive thoughts in perpetuating psychological distress, but he also developed a more systematic way of conceptualizing these cognitions in terms of “schemas” or core beliefs about the self, the world, and the future.

Cognitive therapy (later expanded into cognitive-behavioral therapy or CBT) quickly became one of the most widely practiced and extensively researched forms of psychotherapy, with demonstrated efficacy for a wide range of mental health conditions. Its pragmatic, skills-based approach fit well with the increasing demand for evidence-based, cost-effective treatments in the era of managed care.

However, critics charged that CBT’s emphasis on symptom relief and the correction of supposedly distorted cognitions neglected deeper issues of meaning, value, and interpersonal dynamics. The manualized, protocol-driven format of much CBT also risked reducing therapy to a mechanistic exercise, short-circuiting the crucial process of discovery and meaning-making catalyzed by the therapeutic relationship.

Developmental Psychology and Attachment Theory

Alongside the cognitive revolution, another major stream of influence on psychotherapy came from the field of developmental psychology, particularly the work of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky. Piaget mapped out the stages of cognitive development from infancy to adolescence, highlighting the active, constructive nature of learning and the importance of assimilation and accommodation in adapting to new experiences. Vygotsky, meanwhile, emphasized the social and cultural context of development, arguing that higher mental functions originate in interpersonal interactions and are internalized through the use of cultural tools and symbols.

These insights into the developmental trajectory of the mind had significant implications for psychotherapy, suggesting that many psychological problems could be understood as arrests or deviations in the normal process of cognitive and emotional growth. They also highlighted the importance of the therapeutic relationship as a kind of developmental second chance, a safe and supportive environment in which clients could revisit and rework earlier stages of psychosocial maturation.

Perhaps the most influential application of developmental psychology to psychotherapy came from the work of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth on attachment theory. Bowlby argued that the quality of an infant’s early bonding experiences with caregivers shapes their internal working models of self and other, with secure attachment facilitating healthy emotional development and insecure attachment leading to various forms of psychopathology.

Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation procedure for assessing attachment styles in infants and young children, identifying three main patterns: secure, anxious-resistant, and anxious-avoidant. Later researchers added a fourth category, disorganized attachment, associated with a history of abuse or trauma.

Attachment theory provided a powerful framework for understanding the interpersonal roots of psychological distress and the role of the therapeutic relationship in facilitating corrective emotional experiences. It also inspired the development of new clinical models like Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for couples and Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP) for individuals, which aim to promote secure attachment and emotional processing within the context of an empathic, affirming therapeutic bond.

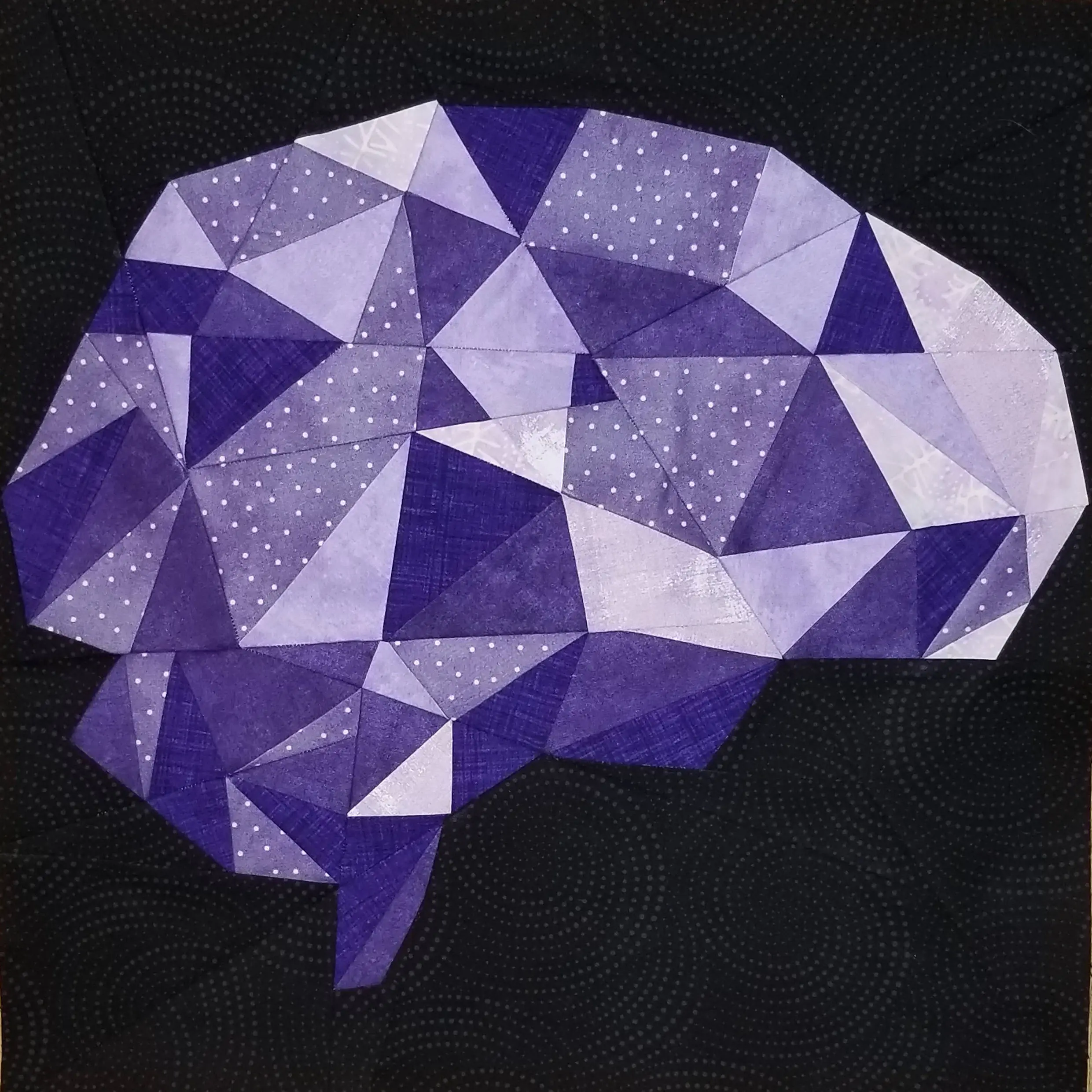

The Neuroexperiential Turn

In recent decades, a new wave of psychotherapies has emerged that seeks to bridge the divide between the cognitive, emotional, and somatic dimensions of experience. Drawing on research in neuroscience, developmental psychology, and trauma studies, these neuroexperiential approaches view the mind as fundamentally embodied and relational, shaped by the interplay of genes, early attachment patterns, and environmental factors.

One pioneer in this area was Wilhelm Reich, a student of Freud’s who developed a system of body-oriented psychotherapy focused on releasing blocked energy and resolving muscular armor. Reich’s work laid the foundation for later somatic approaches like Alexander Lowen’s bioenergetics and Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing.

Another key figure was Arnold Mindell, creator of process-oriented psychology. Mindell emphasizes the nonverbal, somatic, and dreamlike dimensions of experience, which he argues

are always trying to express themselves through symptoms, synchronicities, and subtle body signals. By unfolding these “dreaming processes,” individuals can access new resources for healing and transformation.

More recently, modalities like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), Brainspotting, and Accelerated Resolution Therapy have harnessed the power of bilateral stimulation to help clients process traumatic memories and integrate fragmented parts of the self. These approaches build on the growing understanding of the brain’s innate plasticity and its capacity for rewiring in response to targeted interventions.

Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT), developed by Steven Vazquez, represents an innovative attempt to enhance the precision and efficiency of neuroexperiential methods. By using colored light and other forms of sensory stimulation to activate specific regions of the brain, ETT aims to rapidly transform entrenched emotional patterns and promote psychological integration.

Other significant developments in the neuroexperiential field include:

- Pat Ogden’s Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, which integrates cognitive and somatic interventions to treat attachment and trauma-related disorders

- Laurel Parnell’s Attachment-Focused EMDR, which adapts the standard EMDR protocol to repair early developmental deficits and strengthen the client’s sense of secure attachment

- Bessel van der Kolk’s work on trauma and the body, which highlights the need for integrative, multimodal approaches that address the physiological as well as psychological impact of adverse experiences

- Narrative Exposure Therapy, which uses guided imagery and storytelling to help survivors of complex trauma integrate and transform their memories

Post-Jungian and Transpersonal Developments

Even as the neuroexperiential therapies have gained traction, another stream of innovation has flowed from the post-Jungian and transpersonal traditions, with their emphasis on the creative, mythic, and transcendent dimensions of the psyche.

On the post-Jungian front, a number of influential thinkers have built on Jung’s concepts of archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the individuation process. Anthony Stevens, for example, has sought to ground Jungian theory in evolutionary science, arguing that archetypes are innate, species-typical potentials that have been shaped by natural selection.

Edward Edinger, another prominent post-Jungian, has explored the process of individuation in depth, mapping out the archetypal stages and challenges involved in the journey towards wholeness. James Hillman, the founder of archetypal psychology, has critiqued the individualizing bias of Jungian theory, emphasizing the need to reconnect with the anima mundi or world soul.

In the transpersonal realm, pioneers like Ken Wilber and Stanislav Grof have sought to integrate Eastern contemplative traditions with Western psychology, developing models of human development that encompass the entire spectrum of consciousness from pre-personal to personal to transpersonal levels.

Wilber’s integral theory posits a series of evolutionary stages or “waves” of development, each transcending and including the previous level. He argues that an integral approach to psychotherapy must address all levels and lines of development, from the cognitive and emotional to the spiritual and existential.

Grof, meanwhile, has developed a cartography of the psyche based on his research with non-ordinary states of consciousness induced by breathwork and psychedelics. He describes a series of “perinatal matrices” corresponding to different stages of the birth process, as well as “transpersonal” experiences that transcend the boundaries of individual identity.

Other significant figures in the transpersonal field include:

- Carl Jung himself, whose later work on alchemy, synchronicity, and the collective unconscious laid the groundwork for transpersonal psychology

- Abraham Maslow, who coined the term “self-transcendence” and included it as a capstone stage in his hierarchy of needs

- Roberto Assagioli, the founder of psychosynthesis, which aims to integrate the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual dimensions of the self

- Michael Washburn, whose theory of “transpersonal ego development” describes the higher stages of growth beyond conventional adulthood

Integrative Approaches

In recent years, there has been a growing movement towards integrative approaches that seek to combine the best elements of different theoretical orientations and therapeutic modalities. Rather than adhering to a single school of thought, integrative therapists draw on a wide range of concepts and techniques to tailor their interventions to the unique needs and preferences of each client.

One influential framework for integration is Paul Wachtel’s cyclical psychodynamics, which weaves together insights from psychoanalysis, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and family systems theory. Wachtel argues that psychological problems often arise from vicious cycles of thought, feeling, and behavior that are perpetuated by maladaptive relational patterns. By attending to the moment-to-moment unfolding of these cycles within the therapeutic relationship, therapists can help clients develop new, more adaptive ways of relating to themselves and others.

Another important integrative model is Jeremy Holmes’ attachment-informed psychotherapy, which combines ideas from attachment theory, evolutionary psychology, and neuroscience. Holmes suggests that the therapeutic relationship serves as a “secure base” from which clients can explore their inner and outer worlds, gradually internalizing a sense of safety and resilience.

Other significant developments in the integrative field include:

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), developed by Marsha Linehan, which combines cognitive-behavioral techniques with mindfulness and acceptance practices to treat borderline personality disorder and other emotion regulation difficulties

- Schema Therapy, developed by Jeffrey Young, which integrates concepts from CBT, psychoanalysis, and attachment theory to address deep-rooted maladaptive patterns of thinking and behaving

- Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy (AEDP), developed by Diana Fosha, which harnesses the power of positive emotions and the therapeutic relationship to facilitate deep emotional processing and transformation

Conclusion

As this survey suggests, the history of psychotherapy is in many ways a history of the human struggle to make sense of the mind’s complexity and restore a sense of wholeness to a fragmented psyche. Each new modality and theoretical rebellion has been a kind of puzzle piece, illuminating one facet of the self while obscuring others.

The challenge for contemporary therapists is to develop a more integral vision that can hold these multiple dimensions in creative tension. We need approaches that honor the biological, psychological, social, existential, and spiritual aspects of human experience without collapsing them into a reductionistic framework. We need theories that can accommodate both the universal patterns and the infinite diversity of the psyche, the objective realities of neuroscience and the subjective truths of lived experience.

The path ahead is uncharted and the challenges formidable, but the potential rewards are great. For as we work towards a more holistic and integrative psychology, we also work towards a more whole and healed world. May we have the courage and humility to walk this path with grace, holding fast to the enduring hope and vision of our therapeutic ancestors.

This comprehensive article traces the major schools and movements in the history of psychotherapy, from Freud and the psychoanalytic diaspora to the neuroexperiential and transpersonal paradigms of the present day. It explores how each wave of innovation has built on and reacted against previous approaches, leading to an increasingly complex and multifaceted understanding of the human mind. While celebrating the unique contributions of different theoretical orientations, the article ultimately argues for the need to develop a more integral framework that can accommodate the full spectrum of human experience and potential. As psychotherapy continues to evolve in response to new scientific findings and cultural challenges, this integral vision offers a guiding light for the field’s ongoing quest to alleviate suffering and promote wholeness and well-being.

0 Comments