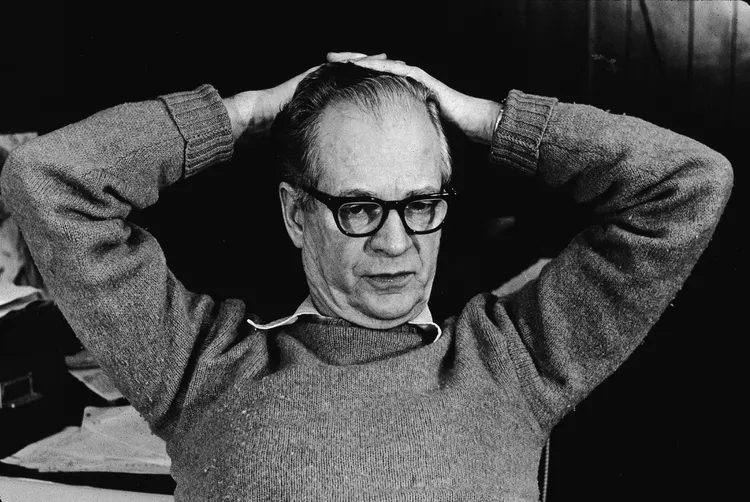

Who was B.F. Skinner?

B.F. Skinner was one of the most influential and controversial psychologists of the 20th century. As the father of radical behaviorism, he revolutionized our understanding of learning, behavior, and conditioning. His pioneering work in operant conditioning, schedules of reinforcement, behavioral shaping, and the experimental analysis of behavior had a profound impact not only on psychology, but fields as diverse as education, child-rearing, psychotherapy, behavioral economics, and even animal training. At the same time, his rejection of internal mental states, radical environmentalism, and utopian social engineering proposals made him a lightning rod for criticism. This essay provides an in-depth exploration of Skinner’s key theories and their enduring legacy.

Operant Conditioning: The Consequences of Behavior

The cornerstone of Skinner’s theory was operant conditioning – the idea that the consequences of a behavior shape the future probability of that behavior occurring again. Unlike classical conditioning, which depends on an association between stimuli, operant conditioning focuses on the association between a behavior and the changes in the environment that follow it. If a behavior is followed by a reinforcing stimulus, it will be strengthened and more likely to occur in the future. If it is followed by an aversive stimulus (or the removal of a reinforcing one), it will be weakened and less likely to reoccur.

Skinner developed this insight through his innovative use of the “Skinner Box” – an apparatus that allowed him to carefully control and measure the behaviors of animals like rats and pigeons in response to varying schedules of reinforcement. By providing food pellets to a rat when it pressed a lever, for example, he could increase the frequency of that behavior. By sounding an unpleasant noise, he could decrease it. These simple yet powerful principles, he argued, governed the behavior of all organisms – including humans.

Schedules of Reinforcement: The Power of Timing

One of Skinner’s key discoveries was the importance of schedules of reinforcement – the precise pattern and timing with which reinforcers are delivered. He found that different schedules produced different patterns of responding and had important implications for the acquisition, maintenance, and extinction of behaviors.

Continuous reinforcement, where every desired response is reinforced, leads to rapid learning but also rapid extinction when reinforcement is withdrawn. Intermittent schedules, where only some responses are reinforced, produce slower acquisition but much greater resistance to extinction. Skinner explored four main types of intermittent schedules:

Fixed Ratio (FR):

reinforcement is delivered after a fixed number of responses (e.g., every 10th lever press).

Variable Ratio (VR):

reinforcement is delivered after an unpredictable number of responses.

Fixed Interval (FI):

reinforcement is delivered for the first response after a fixed time interval has elapsed.

Variable Interval (VI):

reinforcement is delivered for the first response after a variable time interval.

Skinner found that ratio schedules tend to produce high, steady rates of responding, with a brief pause after each reinforcer. Interval schedules produce a scalloped pattern, with a slow rate immediately after reinforcement that increases as the next interval elapses. Variable schedules, in general, produce steadier and more persistent behavior than fixed ones.

These insights had important real-world applications. Slot machines, for example, employ variable ratio schedules to produce addictive levels of responding. Many jobs, from factory work to sales, structure compensation around different reinforcement schedules. Understanding these dynamics, Skinner argued, was key to incentive structures that could evoke the desired behavioral outputs.

Shaping: The Gradual Molding of Behavior

Another of Skinner’s major contributions was the concept of shaping – the process of gradually molding a behavior by selectively reinforcing successive approximations of the desired response. Instead of waiting for an organism to spontaneously emit the target behavior, the shaper rewards behaviors that come progressively closer and closer to it.

Skinner famously demonstrated this process by training pigeons to play ping-pong, peck out the rhythms of songs, and even pilot guided missiles. He started by reinforcing any movement in the right direction, then narrowed the criteria for reinforcement to closer and closer approximations of the final behavior.

Shaping has since become an indispensable tool in behavioral therapy, special education, animal training, and skill acquisition. Therapists use it to mold desired behaviors in children with autism or adults with phobias. Animal trainers shape complex behaviors in dogs, dolphins, and other species. Coaches and teachers use shaping to develop athletic and artistic techniques. Whenever behavior change is the goal, Skinner showed, shaping offers a powerful technology.

The Experimental Analysis of Behavior: A Natural Science Approach

Underlying all of Skinner’s work was his commitment to the experimental analysis of behavior – the study of behavior as a natural science, through controlled experiments and precise quantitative measurement. Skinner rejected the mentalistic concepts and methods of conventional psychology, arguing that internal states were not necessary to predict and control behavior.

Instead, he focused on the observable relationships between environmental variables and behavioral outputs. By carefully manipulating the antecedents and consequences of behavior in the laboratory, he sought to discover the general laws that governed learning and conditioning. This approach led to a wealth of precise, replicable findings about behavioral phenomena like reinforcement, punishment, extinction, generalization, and discrimination.

Skinner’s emphasis on experimental rigor, quantification, and environmental control had a profound influence on the field. It helped to establish behavior analysis as a natural science, on par with fields like biology and physics. It also spawned a range of powerful behavior change technologies, from programmed instruction to applied behavior analysis.

At the same time, Skinner’s radical behaviorism faced significant challenges and criticisms. Many psychologists argued that it neglected the role of cognitive processes, emotions, and internal states in shaping behavior. Others criticized its mechanistic view of humans and its neglect of free will and autonomy. Skinner’s utopian visions of behavioral engineering struck many as authoritarian and dehumanizing.

Verbal Behavior: Language as Learned Behavior

One of Skinner’s most ambitious and controversial works was his 1957 book Verbal Behavior, which attempted to extend the principles of operant conditioning to language acquisition and use. Skinner argued that language was simply another form of operant behavior, shaped by the reinforcing consequences mediated by other speakers.

According to Skinner, verbal behaviors like mands (requests or demands), tacts (labeling or describing), and intraverbals (conversational responses) were acquired and maintained by different kinds of reinforcement contingencies. A child learns to say “cookie” because that verbal operant has been reinforced by receiving cookies in the past. Verbal behaviors are also often reinforced by social attention, approval, or communication itself.

Skinner’s functional analysis of language challenged the prevailing view of language as an innate, rule-governed system. It also had important implications for language instruction, suggesting that verbal skills could be systematically shaped through careful arrangement of reinforcement contingencies.

However, Verbal Behavior was sharply criticized by linguist Noam Chomsky and others, who argued that it failed to account for the generative, rule-governed nature of language. Chomsky argued that children’s language acquisition far outpaced what could be explained by reinforcement history alone, and must rely on innate grammatical structures.

While Verbal Behavior did not overthrow the cognitive revolution in linguistics and psycholinguistics, it did inspire a vibrant research program in the functional analysis of language. Skinner’s emphasis on the environmental determinants of language has been increasingly integrated with cognitive and biological perspectives in modern behavioral science.

Technology of Behavior: Designing Cultures

Perhaps Skinner’s most visionary and controversial ideas concerned the application of behavioral principles to the design of cultures and societies. In works like Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971) and Walden Two (1948), Skinner argued that the problems of the world – war, poverty, inequality, environmental destruction – were ultimately problems of human behavior. And the solution, he believed, lay in applying the science of behavior to social and cultural engineering.

Skinner proposed a technology of behavior – a systematic framework for analyzing the environmental contingencies that shape behavior and designing interventions to change them in socially desirable ways. This could involve anything from redesigning classroom practices to promote effective learning, to restructuring economic incentives to encourage productive and prosocial behavior, to creating entirely new cultural practices and institutions.

In Walden Two, Skinner presented a fictional model of a utopian community based on behavioral principles. In this engineered society, childrearing, education, work, and leisure were all carefully designed to promote happiness, productivity, and social harmony. Positive reinforcement was the primary means of behavioral control, with aversive measures used sparingly and transparently. The goal was to create a culture that brought out the best in human nature and potential.

Critics, however, saw Skinner’s social ideas as a dystopian nightmare – a recipe for totalitarian control and the suppression of human freedom. Skinner’s casual dismissal of concepts like free will, individual rights, and human dignity struck many as chilling. His faith in technocratic design of societies seemed to ignore the complexities of human motivation and the importance of democratic participation.

Despite these criticisms, Skinner’s broader vision of applying behavioral science to improve the human condition has been deeply influential. His emphasis on the importance of environmental contingencies in shaping behavior has informed fields like behavioral economics, public policy, and social psychology. And his utopian ideas, while controversial, raise enduring questions about the potential and perils of consciously directing cultural evolution.

Legacy and Relevance

B.F. Skinner’s impact on psychology and beyond is difficult to overstate. His experimental discoveries in the principles of operant conditioning and schedules of reinforcement laid the foundations for modern behavior analysis. His applications of these principles to domains like education, psychotherapy, and behaviorally-engineered societies pushed the boundaries of psychological science. And his radical behaviorist philosophy challenged our understanding of human nature and the causes of behavior.

While many of Skinner’s specific theories have been challenged, modified, or superseded, his broader intellectual legacy endures. The experimental rigor and quantitative precision he brought to the study of behavior helped establish psychology as a natural science. His insights into the power of selection by consequences to shape behavioral repertoires have been extended into fields like evolutionary psychology and behavioral economics. And his vision of applying behavioral principles to improve the human condition continues to inspire researchers and practitioners.

At the same time, Skinner’s radical stances and utopian speculations remain as controversial as ever. His rejection of mental states and autonomous man strikes many as an impoverished view of human nature. His disregard for human freedom and dignity in favor of behavioral engineering raises troubling ethical questions. And his vision of a behaviorally-designed society sits uneasily with modern commitments to individual liberty and democratic self-determination.

As psychology and society continue to grapple with questions of behavioral influence, social engineering, and the science of human nature, Skinner’s legacy is sure to remain a vital touchstone. While few today would embrace his theories in their entirety, his insights and provocations continue to shape the field. By pushing the boundaries of what a science of behavior can aspire to, Skinner expanded our sense of psychology’s possibilities and responsibilities. As we navigate the promises and perils of new behavioral technologies in the 21st century, engaging with his thought is more vital than ever.

Bibliography

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). “The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis.” Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Skinner, B. F. (1948). “Walden Two.” Macmillan.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). “Science and Human Behavior.” Macmillan.

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). “Verbal Behavior.” Copley Publishing Group.

- Skinner, B. F. (1966). “The Behavior of Organisms: Selected Papers.” Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Skinner, B. F. (1969). “Contingencies of Reinforcement: A Theoretical Analysis.” Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Skinner, B. F. (1971). “Beyond Freedom and Dignity.” Alfred A. Knopf.

- Skinner, B. F. (1974). “About Behaviorism.” Vintage Books.

- Skinner, B. F. (1976). “Particulars of My Life: Part One of an Autobiography.” Knopf.

- Skinner, B. F. (1983). “A Matter of Consequences: Part Two of an Autobiography.” Knopf.

- Skinner, B. F. (1987). “Upon Further Reflection.” Prentice-Hall.

- Skinner, B. F. (1990). “Recent Issues in the Analysis of Behavior.” Merrill Publishing Company.

- Skinner, B. F. (1991). “Cumulative Record: Definitive Edition.” Merrill Publishing Company.

- Baum, W. M. (Ed.). (1989). “Everyday Behavior Analysis.” M. L. Cummings.

- Catania, A. C. (Ed.). (1990). “Contemporary Issues in Behavior Therapy: Improving the Human Condition.” Allyn & Bacon.

- Cohen, D. (Ed.). (1996). “Behavioral Self-Management: Strategies, Techniques, and Outcomes.” Brunner/Mazel.

- Morris, E. K., & Laitinen, A. (Eds.). (1995). “Behavior Analysis in Theory and Practice: Contributions and Controversies.” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Poling, A., & Fuqua, R. W. (Eds.). (1999). “Research Methods in Applied Behavior Analysis: Issues and Advances.” Context Press.

- Skinner, B. F., & Ferster, C. B. (1957). “Schedules of Reinforcement.” Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Vaughan, M. E., & Michael, J. (Eds.). (1982). “Psychology of the Future: Lessons from Modern Consciousness Research.” State University of New York Press.

Cognitive and Behavioral Psychologists

0 Comments