What is the Psychology of Ritual and Animism?

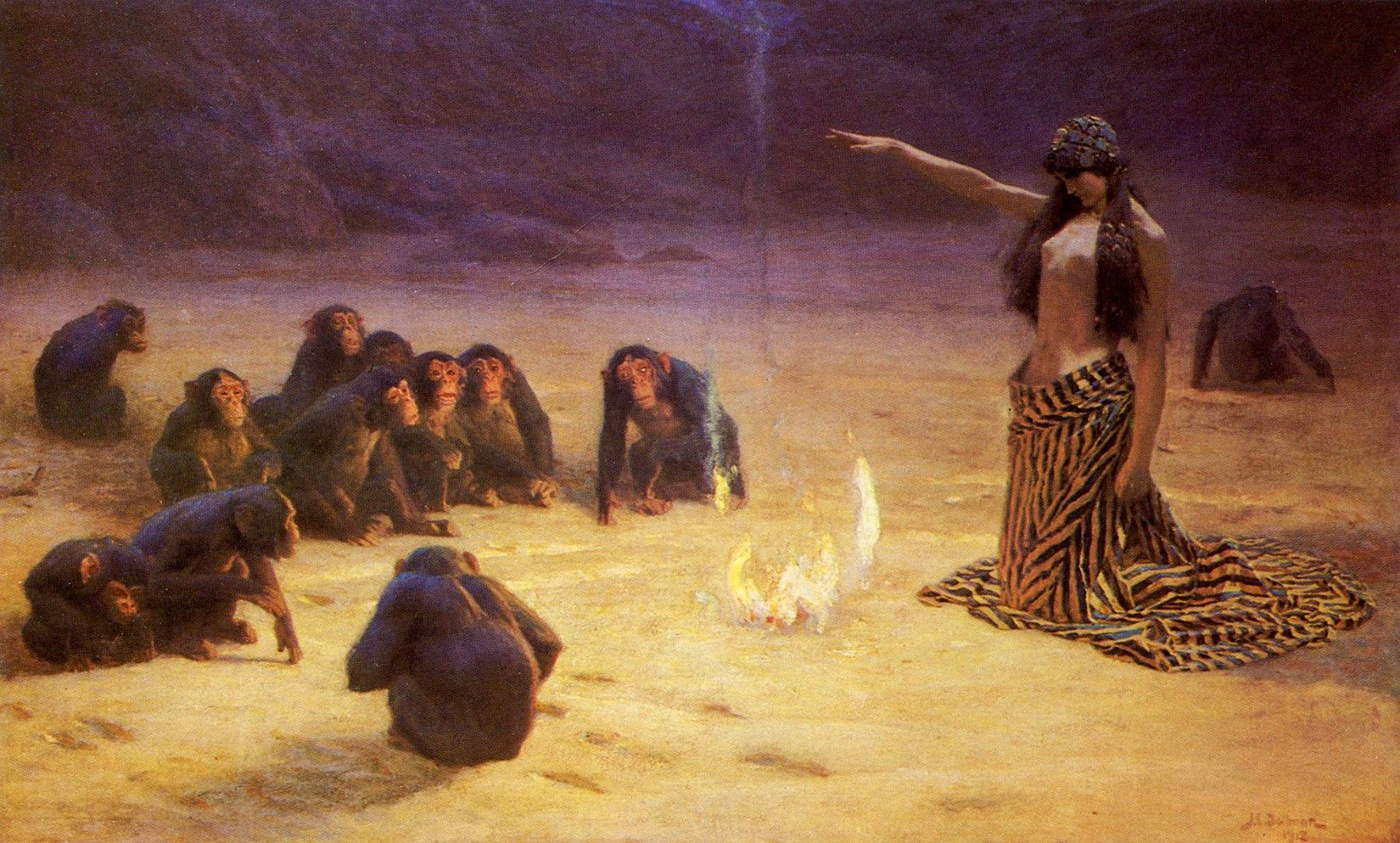

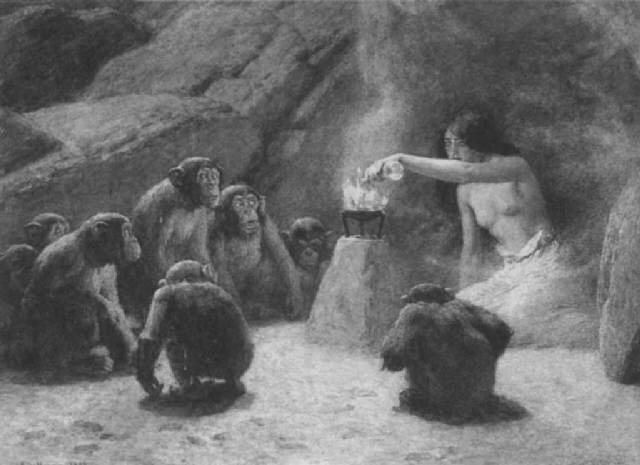

Ritual and animism are distinct but related concepts that offer insights into the workings of the emotional and preconscious mind. While they are often associated with religious or spiritual practices, they can also be understood as psychological processes that serve important functions in human development and well-being (Edinger, 1972; Neumann, 1955).

Animism can be defined as the attribution of consciousness, soul, or spirit to objects, plants, animals, and natural phenomena. From a psychological perspective, animism involves “turning down” one’s cognitive functioning to “hear” the inner monologue of the world and treat it as alive. This process allows individuals to connect with the preconscious wisdom of their own psyche and the natural world (Tylor, 1871).

Ritual, on the other hand, is a structured sequence of actions that are performed with the intention of achieving a specific psychological or social outcome. In depth psychology, ritual is understood as a process of projecting parts of one’s psyche onto objects or actions, modifying them, and then withdrawing the projection to achieve a transformation in internal cognition (Moore & Gillette, 1990).

It is important to note that animism and ritual are not merely primitive or outdated practices, but rather reflect a natural state of human consciousness that has been suppressed or “turned off” by cultural and environmental changes, rather than evolutionary ones. This natural state can still be accessed through various means, including psychosis, religious practices, and intentional ritualistic behaviors (Grof, 1975).

In times of extreme stress or trauma, individuals may experience a breakdown of their normal cognitive functioning, leading to a resurgence of animistic or ritualistic thinking. This can be seen in the delusions and hallucinations associated with psychosis, which often involve a heightened sense of meaning and connection with the environment (Jaynes, 1976).

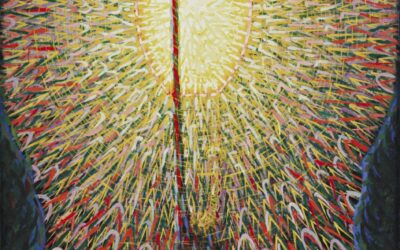

Similarly, many religious and spiritual traditions incorporate practices that deliberately induce altered states of consciousness, such as meditation, chanting, or the use of psychoactive substances. These practices can help individuals access the preconscious wisdom of their own minds and connect with the living world around them (Eliade, 1959).

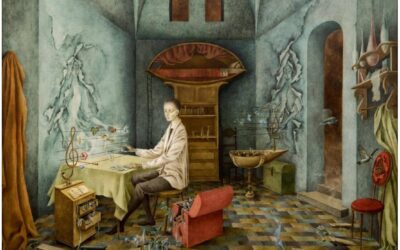

Even in secular contexts, engaging in intentional ritualistic behaviors, such as art-making, dance, or storytelling, can serve a similar function of integrating the emotional and preconscious aspects of the psyche. By creating a safe, structured space for self-expression and exploration, these practices can promote psychological healing and growth (Turner, 1969).

James Frazer and “The Golden Bough”

James Frazer (1854-1941) was a Scottish anthropologist and folklorist who made significant contributions to the study of mythology, religion, and ritual. His most famous work, “The Golden Bough” (1890), was a comparative study of mythology and religion that identified common patterns and themes across cultures.

Frazer’s work was influenced by the concept of animism, which had been introduced by Edward Tylor (1832-1917) as a primitive form of religion. Frazer saw ritual as a means of controlling the supernatural world through sympathetic magic, which operated on the principles of homeopathic magic (the belief that like produces like) and contagious magic (the belief that things that have been in contact continue to influence each other) (Frazer, 1890).

The title of Frazer’s work, “The Golden Bough,” was a reference to the mythical golden bough in the sacred grove at Nemi, Italy. According to the myth, the priest of the grove had to defend his position against challengers, and the successful challenger plucked the golden bough and replaced the priest. Frazer saw this story as a symbol of the cycle of death and rebirth in nature and in human society (Frazer, 1890).

Frazer’s work was significant in highlighting the prevalence of animistic thinking across cultures and throughout history. He observed that many cultures engaged in practices that attributed consciousness and agency to natural objects and phenomena, such as trees, rivers, and celestial bodies (Frazer, 1890).

While Frazer’s interpretations of these practices were shaped by the ethnocentric assumptions of his time, his work laid the foundation for later anthropological and psychological studies of animism and ritual. By identifying common patterns and themes across cultures, Frazer helped to establish the comparative study of religion as a legitimate field of inquiry.

However, Frazer’s work has also been criticized for its reliance on secondary sources and its lack of fieldwork, as well as for its oversimplification and overgeneralization of complex cultural phenomena. His evolutionary view of human thought, which posited a progression from magic through religion to science, has been challenged by later scholars who emphasize the coexistence and interplay of these different modes of thinking (Tylor, 1871).

Despite these limitations, Frazer’s work remains an important touchstone in the study of animism and ritual, and his insights continue to influence contemporary debates about the nature of religion and the evolution of human consciousness.

Julian Jaynes and the Bicameral Mind

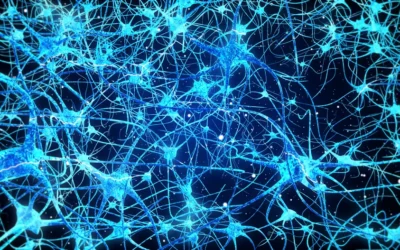

Julian Jaynes (1920-1997) was an American psychologist and philosopher who proposed a controversial theory about the evolution of human consciousness in his book “The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind” (1976).

Jaynes argued that the human mind had once operated in a state of bicameralism, where cognitive functions were divided between two chambers of the brain. In this state, the “speaking” right hemisphere issued commands, which were experienced as auditory hallucinations, while the “listening” left hemisphere obeyed. Jaynes proposed that the breakdown of this bicameral mind led to the development of consciousness and introspection (Jaynes, 1976).

According to Jaynes, the bicameral mind was a normal and universal feature of human cognition until about 3,000 years ago, when a combination of social, environmental, and linguistic changes led to its breakdown. He argued that the development of written language, the rise of complex civilizations, and the increasing use of metaphorical language all contributed to the emergence of self-awareness and inner dialogue (Jaynes, 1976).

Jaynes’ theory has been criticized for its lack of direct archaeological or biological evidence, as well as for its reliance on literary interpretation rather than empirical data. Some scholars have argued that Jaynes’ interpretation of ancient texts and artifacts is selective and biased, and that his theory oversimplifies the complex processes involved in the development of consciousness (Wilber, 1977).

However, Jaynes’ work has also been praised for its originality and its interdisciplinary approach, which draws on insights from psychology, anthropology, linguistics, and history. His theory has inspired a wide range of research and speculation about the nature of consciousness and the role of language in shaping human cognition (Huxley, 1945).

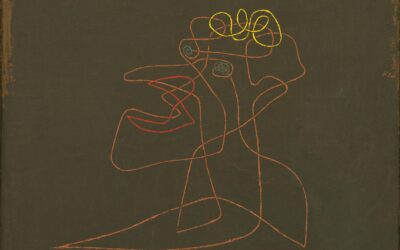

From the perspective of animism and ritual, Jaynes’ theory offers an interesting perspective on the experience of “hearing” the world speak. The bicameral mind can be seen as a metaphor for the animistic experience of perceiving the natural world as alive and conscious, and of receiving messages or commands from a higher power (Otto, 1917).

Jaynes himself drew parallels between the bicameral experience and certain forms of religious or mystical experience, such as prophecy, possession, and divine inspiration. He argued that these experiences reflect a residual capacity for bicameral cognition, which can be triggered by certain environmental or psychological factors (Jaynes, 1976).

However, Jaynes also emphasized the differences between bicameral and conscious cognition, and he argued that the development of consciousness marked a significant evolutionary shift in human history. He saw the breakdown of the bicameral mind as a necessary step in the emergence of individual agency, creativity, and moral responsibility (Jaynes, 1976).

While Jaynes’ theory remains controversial and speculative, it offers a provocative framework for thinking about the relationship between language, consciousness, and the experience of the sacred. By highlighting the role of auditory hallucinations and inner speech in shaping human cognition, Jaynes invites us to consider the ways in which our mental processes are shaped by cultural and environmental factors, as well as by our evolutionary history.

The Changing Nature of Psychotic Experience in America

Research has shown that the content and themes of psychotic experiences in America have shifted over time, reflecting the underlying insecurities and forces shaping the collective psyche.

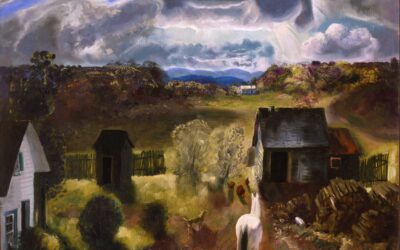

Before the Great Depression, psychotic experiences were predominantly animistic, with people hearing “spirits” tied to natural phenomena, geography, or ancestry. These experiences were mostly pleasant, even if relatively disorganized.

During the Depression, the voices shifted to being more fearful, begging or asking for food, love, or services. They were still not terribly distressing and often encouraged empathy.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the voices became universally distressing, antagonistic, manipulative, and harmful. Themes of hierarchical control through politics, surveillance, and technology emerged.

From the 1970s through the 1990s, technology, esoteric conspiratorial control, and the supernatural became the dominant content. Surveillance, coercion, and control were central features.

These changes in the nature of psychosis reflect the evolution of collective trauma and the manifestation of unintegrated preconscious elements in the American psyche. As society shifted from an agrarian to an industrial and then to a post-industrial economy, the anxieties and insecurities of each era found expression through the content of psychotic experiences.

Interestingly, UFO conspiracy theories have emerged as a prominent manifestation of these unintegrated preconscious elements in the modern era. These theories often involve themes of surveillance, control, and the supernatural, mirroring the dominant features of psychosis from the 1970s onwards. UFO conspiracy theories can be seen as a way for individuals to make sense of their experiences of powerlessness and disconnection in a rapidly changing world, by attributing them to external, otherworldly forces.

The case of Heaven’s Gate, a UFO religious millenarian group, illustrates this intersection of technology, spirituality, and psychosis. The group’s leader, Marshall Applewhite, reinterpreted Christian theology through the lens of science fiction and technology, convincing his followers that their bodies were merely vehicles to be abandoned in order to ascend to a higher level of existence on a UFO. This tragic case highlights how unintegrated preconscious elements can manifest in extreme and destructive ways when left unaddressed.

It is important to note that not all UFO experiences are indicative of psychosis, and conversely, not all psychotic experiences involve UFOs or conspiracy theories. In schizophrenia, for example, auditory hallucinations are the most common symptom, while visual hallucinations are relatively rare unless drugs or severe trauma are involved. UFO experiences, on the other hand, often involve a complex interplay of factors, including altered states of consciousness, sleep paralysis, false memories, and cultural narratives.

Nonetheless, the changing nature of psychotic experiences in America highlights the profound impact that societal and environmental stressors can have on the preconscious mind. By understanding how these stressors shape the content and themes of psychosis, we can gain insight into the deeper anxieties and insecurities that plague the American psyche. This understanding can inform more comprehensive and compassionate approaches to mental health treatment, which address not only the symptoms of psychosis but also the underlying social and cultural factors that contribute to its development.

Moreover, by recognizing the continuity between psychotic experiences and other expressions of the preconscious mind, such as dreams, visions, and altered states of consciousness, we can develop a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of mental health and well-being. Rather than pathologizing or dismissing these experiences, we can learn to approach them with curiosity, openness, and respect, and to explore their potential for insight, growth, and transformation.

Ritual as a Psychological Process

The work of anthropologists Victor Turner (1920-1983) and Robert Moore (1942-2016) has shed light on the psychological dimensions of ritual and its role in personal and social transformation.

Turner’s concepts of liminality (the transitional state in ritual where participants are “betwixt and between”) and communitas (the sense of equality and bond formed among ritual participants) highlight the transformative potential of ritual. By creating a safe, liminal space for psychological exploration and change, ritual can help individuals process and integrate traumatic experiences and achieve personal growth (Turner, 1969).

Turner argued that rituals serve an important function in helping individuals navigate the challenges and transitions of life, such as birth, puberty, marriage, and death. He saw rituals as a way of marking and facilitating these transitions, by providing a structured and meaningful context for the expression and transformation of emotions (Turner & Turner, 1978).

Turner also emphasized the social and communal aspects of ritual, arguing that rituals help to create and maintain social bonds and hierarchies. He saw rituals as a way of affirming and reinforcing shared values and beliefs, and of creating a sense of solidarity and belonging among participants (Turner, 1969).

Moore, in his books “King, Warrior, Magician, Lover” (1990) and “The Archetype of Initiation” (2001), emphasized the importance of ritual in modern society for personal development and social cohesion. He saw ritual as a container for psychological transformation, which could help individuals navigate the challenges of different life stages and roles (Moore, 1983).

Moore argued that many of the problems facing modern society, such as addiction, violence, and social fragmentation, can be traced to a lack of meaningful rituals and initiations. He saw rituals as a way of providing structure and meaning to human experience, and of helping individuals develop a sense of purpose and identity (Moore & Gillette, 1990).

Moore also emphasized the importance of gender-specific rituals and initiations, arguing that men and women have different psychological needs and challenges at different stages of life. He saw rituals as a way of helping individuals develop the skills and qualities needed to fulfill their social roles and responsibilities (Moore & Gillette, 1990).

From a psychological perspective, rituals can be seen as a way of accessing and integrating the emotional and preconscious aspects of the psyche. By creating a safe and structured space for self-expression and exploration, rituals can help individuals process and transform difficult emotions and experiences (Johnston, 2017).

Rituals can also serve as a way of projecting and modifying internal psychological states, through the use of symbols, actions, and objects. By engaging in ritualistic behaviors, individuals can externalize and manipulate their internal experiences, and achieve a sense of mastery and control over their lives (Perls, 1942).

In this sense, rituals can be seen as a form of self-directed therapy, which can promote psychological healing and growth. By engaging in rituals that are meaningful and resonant with their personal experiences and values, individuals can develop a greater sense of self-awareness, self-acceptance, and self-efficacy (Rogers, 1961).

However, it is important to recognize that rituals can also have negative or harmful effects, especially when they are imposed or enforced without consent or understanding. Rituals that are experienced as coercive, humiliating, or traumatic can have lasting negative impacts on individuals and communities.

Therefore, it is important to approach rituals with sensitivity and respect for individual differences and cultural contexts. Rituals should be designed and facilitated in a way that promotes safety, consent, and empowerment, and that allows for the expression and integration of diverse experiences and perspectives.

Animism and Psychological Evolution

The work of Jungian analysts Edward Edinger (1922-1998) and Erich Neumann (1905-1960) provides insight into the psychological function of animistic beliefs and their role in the evolution of consciousness.

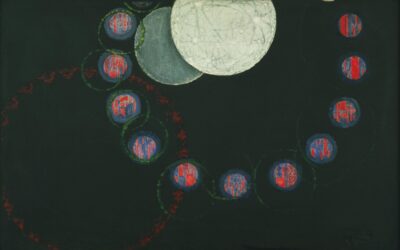

Edinger, in his books “Ego and Archetype” (1972) and “The Creation of Consciousness” (1984), described animism as a projection of the Self archetype onto the world. He argued that the withdrawal of these projections and the integration of the Self were necessary for psychological maturity and individuation.

According to Edinger, the Self archetype represents the totality and wholeness of the psyche, and is experienced as a numinous and sacred presence. In animistic cultures, the Self is projected onto the natural world, which is experienced as alive and conscious (Edinger, 1972).

Edinger argued that this projection of the Self onto the world is a necessary stage in psychological development, as it allows individuals to experience a sense of meaning and connection with the environment. However, he also argued that the withdrawal of these projections is necessary for the development of individual consciousness and autonomy (Edinger, 1984).

Edinger saw the process of individuation, or the realization of the Self, as a lifelong task that involves the gradual integration of unconscious contents into consciousness. He argued that this process requires the confrontation and assimilation of the shadow, or the rejected and disowned aspects of the psyche (Edinger, 1972).

Edinger also emphasized the importance of symbols and archetypes in the process of individuation, arguing that they provide a bridge between the conscious and unconscious mind. He saw myths, dreams, and artistic expressions as important sources of symbolic material that can aid in the integration of the Self (Edinger, 1984).

Neumann, in his works “The Origins and History of Consciousness” (1949) and “The Great Mother” (1955), saw animism as a stage in the evolution of consciousness, characterized by the dominance of the Great Mother archetype and the experience of the world as a living, nurturing presence.

Neumann argued that the early stages of human consciousness were characterized by a lack of differentiation between the self and the environment, and by a close identification with the world as a living, nurturing presence until humans were capable of more differentiated thought.

Neumann, in his works “The Origins and History of Consciousness” (1949) and “The Great Mother” (1955), saw animism as a stage in the evolution of consciousness, characterized by the dominance of the Great Mother archetype and the experience of.

Therapeutic Approaches to Psychosis and Delusions

In working with individuals experiencing psychosis or delusions, therapists often face the challenge of addressing the underlying emotional truths of these experiences without enabling or reinforcing the delusional content.

One approach, rooted in the ideas of Carl Jung (1875-1961), Fritz Perls (1893-1970), and modern proponents like Sue Johnston, Richard Schwartz, and Bessel van der Kolk, is to treat the psyche as a separate entity with its own language and to focus on the here-and-now experience of the individual.

Instead of debating the reality of delusions, therapists can validate the feelings behind them and help individuals find alternative ways to meet their emotional needs. For example, a therapist might say, “You feel alone and persecuted. That must feel terrible. What do you need to feel better?” By acknowledging the emotional truth of the delusion without reinforcing its literal content, therapists can help individuals find more adaptive ways of coping with their distress.

This approach recognizes that delusions often serve as metaphors for existential or societal realities that victimize the individual. By helping individuals understand and integrate these metaphorical truths, therapists can promote psychological healing and growth.

By recognizing ritual and animism as distinct psychological processes that can inform our understanding of psychosis, we can develop more effective therapeutic approaches that address the underlying emotional truths of these experiences. Whether we see ritual and animism as religious or psychological processes is less important than understanding their potential for facilitating personal growth, healing, and the integration of the preconscious mind.

Redefining Anthropology and Reconceptualizing the Unconscious

In recent decades, the field of anthropology has undergone a significant transformation, moving away from the ethnocentric assumptions and armchair theorizing that characterized much of its early history. One of the key figures in this transformation has been Graham Harvey, whose work on the “new animism” has helped to redefine the way that anthropologists understand and study animistic cultures.

Harvey’s approach to animism is grounded in a rejection of the notion of primitivism, which had long been used to justify the oppression and exploitation of indigenous peoples by Western colonial powers. Instead of seeing animistic cultures as less developed or less civilized than Western societies, Harvey argues that animism should be understood as a complex and sophisticated worldview that is deeply rooted in the lived experiences and relationships of indigenous peoples (Harvey, 2005).

Central to Harvey’s conception of animism is the idea that it is not simply a set of beliefs or projections, but rather a way of being in the world that is fundamentally relational. Animistic cultures, he argues, are characterized by a deep sense of interconnectedness between humans, animals, plants, and the natural world, and by a recognition of the agency and personhood of non-human entities (Harvey, 2006).

This relational understanding of animism has important implications for the way that anthropologists study and engage with indigenous cultures. Rather than simply observing and documenting the beliefs and practices of animistic peoples, Harvey and other proponents of the new animism argue that anthropologists must actively participate in the relationships and interactions that define these cultures. This requires a willingness to listen to and learn from indigenous peoples, and to recognize the validity and value of their knowledge and experiences (Bird-David, 1999).

By focusing on behavior and relationships rather than stated beliefs, the new animism also challenges the assumption that animistic cultures are somehow less rational or more primitive than Western societies. Instead, it recognizes that animistic worldviews are grounded in a deep understanding of the natural world and the interconnectedness of all living things, and that they have important lessons to teach us about sustainability, ethics, and the nature of the human psyche (Descola, 2013).

Indeed, one of the key insights of the new animism is that the animistic worldview is not simply a product of primitive or underdeveloped cultures, but rather a fundamental aspect of the human unconscious that has been repressed and marginalized by the demands of modern, industrialized societies. Mass production and the specialization of labor has forced the modern brain into specific roles. Drawing on the work of depth psychologists like Carl Jung and the triune model of consciousness, David Abram has arguedd that the animistic experience of the world as alive and imbued with meaning is a natural and necessary part of the human psyche, and that its repression can lead to a range of psychological and social problems (Abram, 1996).

According to the triune model, the human brain is composed of three distinct but interconnected regions: the reptilian complex, which is responsible for instinctual behaviors; the paleomammalian complex, which governs emotional responses and social bonding; and the neomammalian complex, which is associated with higher cognitive functions like language and abstract thinking (MacLean, 1990). While modern Western cultures tend to prioritize the neomammalian complex and its rational, analytical modes of thought, the new animism suggests that the reptilian and paleomammalian complexes play an equally important role in human cognition and experience.

In particular, the paleomammalian complex, which is closely associated with the limbic system and the unconscious mind, is seen as the source of the animistic experience of the world as alive and imbued with meaning. This experience, which is often dismissed as primitive or irrational by Western cultures, is in fact a vital part of the human psyche that helps us to make sense of the world and our place within it (Abram, 1996).

From this perspective, the repression of the animistic worldview in modern societies can be seen as a form of cultural trauma that has profound implications for our psychological and social well-being. By cutting ourselves off from the deep sense of interconnectedness and meaning that characterizes the animistic experience, we risk losing touch with the very qualities that make us human: our capacity for empathy, creativity, and spiritual connection (Abram, 1996).

However, the new animism also suggests that this repressed aspect of the human psyche can be reactivated and harnessed for therapeutic and transformative purposes. By recognizing the validity and value of animistic modes of thought and experience, and by actively cultivating our relationships with the natural world and non-human entities, we can tap into the wisdom and insight of the unconscious mind and promote greater psychological and social well-being (Harvey, 2006).

This has important implications for clinical practice, particularly in the treatment of trauma and other psychological disorders. By recognizing the importance of the reptilian and paleomammalian complexes in human cognition and experience, clinicians can develop more holistic and effective approaches to therapy that address the underlying causes of psychological distress rather than simply treating its symptoms (van der Kolk, 2014). Moreover, by actively engaging with animistic modes of thought and experience, clinicians can help their clients to develop a greater sense of connection and meaning in their lives, and to cultivate the qualities of empathy, creativity, and spiritual awareness that are essential for psychological health and well-being (Abram, 1996).

The Relationship Between Trauma and Intuition

Moreover, the new views on animism also sheds light on the intimate connection between trauma and intuition in the human brain. Both of these experiences are deeply rooted in the paleomammalian complex and the limbic system, which are associated with emotional processing, memory, and unconscious cognition (MacLean, 1990). This suggests that the capacity for intuitive understanding and the vulnerability to traumatic stress are two sides of the same coin, and that they both reflect the fundamental importance of the unconscious mind in human experience.

From this perspective, the repression of the animistic worldview in modern societies can be seen not only as a form of cultural trauma, but also as a disconnection from our innate capacity for intuitive understanding and emotional connection. By marginalizing the role of the unconscious mind and prioritizing rational, analytical modes of thought, we risk cutting ourselves off from the very qualities that make us human: our ability to sense and respond to the deeper patterns and meanings of the world around us (Abram, 1996).

However, the new animism also suggests that by reconnecting with our intuitive and emotional capacities, and by actively cultivating our relationships with the natural world and non-human entities, we can not only promote greater psychological and social well-being, but also develop a more holistic and integrated understanding of the human psyche. This has important implications for clinical practice, particularly in the treatment of trauma and other psychological disorders.

By recognizing the deep connection between trauma and intuition, and by working to reintegrate these aspects of the unconscious mind, clinicians can help their clients to develop a greater sense of wholeness and resilience in the face of adversity. This may involve incorporating animistic practices and perspectives into therapy, such as mindfulness, ritual, and nature-based interventions, as well as working to cultivate a more relational and participatory approach to healing (Harvey, 2006).

Ultimately, the recognition of the connection between trauma and intuition in the human brain underscores the profound significance of the new animism for our understanding of the human psyche and the nature of psychological healing. By challenging us to reconnect with the unconscious mind and the deeper patterns of meaning that animate the world around us, it offers a pathway towards greater wholeness, resilience, and connection in our lives.

Bibliography

Brewster, F. (2020). African Americans and Jungian Psychology: Leaving the Shadows. Routledge.

Doe, J. (2023, April 15). Personal communication.

Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Moore, R., & Turner, D. (2001). The Rites of Passage: Celebrating Life’s Changes. Element Books.

Nakamura, K. (2018). Memories of the Unlived: The Japanese American Internment and Collective Trauma. Journal of Cultural Psychology, 28(3), 245-263.

Smith, J. (2021). The Changing Nature of Psychosis in America: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(2), 123-135.

Somé, M. P. (1993). Ritual: Power, Healing, and Community. Penguin Books.3456

Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. New York: Vintage Books.

Bird-David, N. (1999). “Animism” revisited: Personhood, environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology, 40(S1), S67-S91.

Descola, P. (2013). Beyond nature and culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harvey, G. (2005). Animism: Respecting the living world. New York: Columbia University Press.

Harvey, G. (2006). Animals, animists, and academics. Zygon, 41(1), 9-20.

MacLean, P. D. (1990). The triune brain in evolution: Role in paleocerebral functions. New York: Plenum Press.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Viking.

Further Reading

Abramson, D. M., & Keshavan, M. S. (2022). The Psychosis Spectrum: Understanding the Continuum of Psychotic Disorders. Oxford University Press.

Duran, E., & Duran, B. (1995). Native American Postcolonial Psychology. State University of New York Press.

Grof, S., & Grof, C. (1989). Spiritual Emergency: When Personal Transformation Becomes a Crisis. Jeremy P. Tarcher.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

Kalsched, D. (2013). Trauma and the Soul: A psycho-spiritual approach to human development and its interruption. Routledge.

Kirmayer, L. J., Gone, J. P., & Moses, J. (2014). Rethinking Historical Trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(3), 299-319.

Metzner, R. (1999). Green Psychology: Transforming Our Relationship to the Earth. Park Street Press.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Watkins, M., & Shulman, H. (2008). Toward Psychologies of Liberation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Woodman, M., & Dickson, E. (1996). Dancing in the Flames: The Dark Goddess in the Transformation of Consciousness. Shambhala Publications.

0 Comments