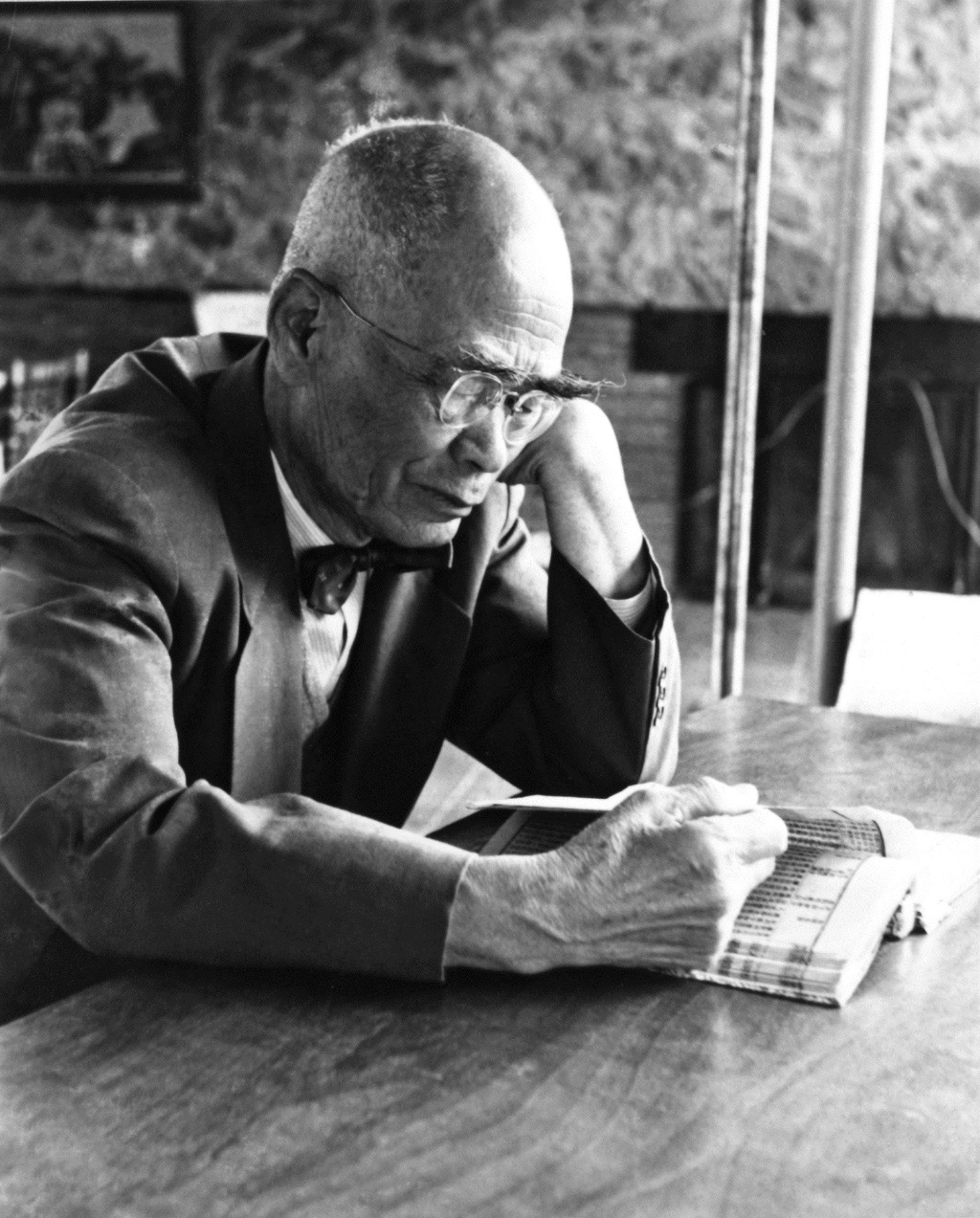

D.T. Suzuki

Who was D.T. Suzuki

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki (1870-1966), better known as D.T. Suzuki, was a pivotal figure in the introduction of Zen Buddhism to the West. A prolific writer, lecturer, and translator, Suzuki played a key role in shaping the Western understanding of Zen and its influence on Japanese culture. His work bridged Eastern and Western thought, sparking a fascination with Zen that continues to this day. This essay provides an in-depth exploration of Suzuki’s life, key ideas, and enduring impact on the fields of comparative religion, psychology, and intercultural dialogue.

1. Early Life and Education

Suzuki was born in Kanazawa, Japan, in 1870. Raised in a Samurai family, he was exposed to Buddhism from a young age. As a teenager, Suzuki studied English and became interested in Western philosophy. He went on to study at the University of Tokyo, where he majored in Buddhist philosophy.

After graduating, Suzuki worked as a translator and teacher of English. In 1897, he traveled to the United States to work as a translator at Open Court Publishing Company in Illinois. There, he began translating the works of the influential Zen master Shaku Sōen, who had been a delegate to the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893.

2. Zen Studies and Training

While working in the United States, Suzuki deepened his own study and practice of Zen. He returned to Japan in 1909 and became a disciple of Shaku Sōen at Engakuji monastery in Kamakura. Under Sōen’s guidance, Suzuki underwent rigorous Zen training, including the practice of zazen (sitting meditation) and koan study.

Suzuki’s firsthand experience with Zen practice informed his unique perspective as a scholar and interpreter of the tradition. He emphasized the experiential dimension of Zen, arguing that it could not be fully grasped through intellectual study alone. For Suzuki, Zen was a way of life, a direct pointing to the nature of reality beyond conceptual understanding.

3. Writing and Teaching Career

In 1911, Suzuki returned to the United States to work as a lecturer at the University of Tokyo. He began publishing books and articles in English, introducing Zen to Western audiences. His first major work, “Essays in Zen Buddhism” (1927), was a collection of his lectures and became a seminal text in the field.

Over the next several decades, Suzuki produced a vast body of work, including books, essays, and translations of classic Zen texts. Some of his most influential works include “An Introduction to Zen Buddhism” (1934), “Zen and Japanese Culture” (1938), and “Mysticism: Christian and Buddhist” (1957). Suzuki’s writing was characterized by a clear, engaging style that made complex ideas accessible to a wide audience.

In addition to his writing, Suzuki lectured extensively in Japan, Europe, and the United States. He taught at universities and Zen centers, including Claremont Graduate School in California and Columbia University in New York. Suzuki’s dynamic teaching style and charismatic presence made a deep impression on his students, many of whom went on to become prominent scholars and practitioners of Zen in their own right.

4. Key Ideas and Contributions

4.1. The Zen Experience

At the heart of Suzuki’s understanding of Zen was the notion of the “Zen experience” – a direct, intuitive grasp of reality that transcends conceptual thinking. For Suzuki, this experience was the essence of Zen practice and the key to unlocking its transformative potential.

Suzuki described the Zen experience as a “state of consciousness” characterized by a sense of oneness, non-duality, and absolute presence. In this state, the ordinary distinctions between self and other, subject and object, fall away. One experiences reality as it is, prior to the divisions imposed by language and conceptual thought.

For Suzuki, the Zen experience was not a mystical trance or an escape from the world, but a way of fully engaging with life as it unfolds moment by moment. It was a dynamic, creative state that enables one to respond spontaneously and wholeheartedly to each situation. The Zen master, in Suzuki’s view, embodies this state of consciousness, acting with effortless grace and precision in all circumstances.

4.2. Zen and Japanese Culture

Suzuki was deeply interested in the relationship between Zen and Japanese culture. He argued that Zen had exerted a profound influence on all aspects of Japanese life, from art and aesthetics to martial arts and everyday etiquette.

In his book “Zen and Japanese Culture,” Suzuki explored how the Zen ethos of simplicity, directness, and spontaneity had shaped traditional Japanese arts like poetry, calligraphy, tea ceremony, and gardening. He showed how these arts served as vehicles for expressing and cultivating the Zen state of mind, with their emphasis on mindfulness, economy of means, and attunement to the present moment.

Suzuki also examined the influence of Zen on the Japanese warrior tradition, particularly the way of the samurai. He argued that Zen training had enabled the samurai to face death with equanimity and to act with fearless resolve in the heat of battle. The Zen ideal of “no-mind” (mushin) – a state of relaxed alertness and spontaneous responsiveness – was central to the martial arts, from archery to swordsmanship.

For Suzuki, the pervasive influence of Zen on Japanese culture was a testament to its transformative power. Zen was not just a religion or a philosophy, but a way of being in the world that could infuse every aspect of life with greater depth, meaning, and vitality.

4.3. Zen and Western Thought

Suzuki was a pioneer in the comparative study of Zen and Western thought. He drew parallels between Zen and various Western philosophical and religious traditions, from Christian mysticism to Jungian psychology.

In his book “Mysticism: Christian and Buddhist,” Suzuki explored the similarities between the insights of the great Christian mystic Meister Eckhart and those of the Zen masters. He argued that both pointed to a direct, immediate experience of reality that transcended doctrinal differences. Suzuki saw in Eckhart’s notion of the “Godhead” – the ineffable source beyond all dualities – a parallel to the Zen understanding of the absolute.

Suzuki also engaged with Western psychology, particularly the work of Carl Jung. He saw in Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious a resonance with the Zen notion of the “Mind” – the universal, non-dual awareness that underlies all individual minds. Suzuki believed that Zen practice could provide a direct route to accessing this deeper level of the psyche and integrating its contents into conscious awareness.

In his dialogues with Western thinkers, Suzuki sought to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western world-views. He believed that Zen offered a fresh perspective on perennial human questions – the nature of the self, the meaning of life, the possibility of transformation. At the same time, he was open to insights from Western traditions that could enrich and expand the understanding of Zen.

4.4. Language and Silence

Suzuki was acutely aware of the limitations of language in conveying the Zen experience. He emphasized that Zen was not a system of thought that could be grasped through words and concepts, but a direct pointing to reality that ultimately transcended language.

In his writings, Suzuki often used paradox, poetry, and humor to subvert the reader’s ordinary conceptual mind and evoke a more intuitive understanding. He drew on the rich tradition of Zen literature – the koans, haiku, and enigmatic sayings of the masters – to convey the flavor of the Zen experience.

At the same time, Suzuki recognized the necessity of language as a tool for communication and teaching. He sought to use language skillfully, to point beyond itself to the wordless truth of Zen. His writing style was direct, concrete, and often playful, reflecting the Zen emphasis on simplicity and spontaneity.

Ultimately, for Suzuki, the deepest understanding of Zen arose in silence – the profound, pregnant silence of zazen, or the thunderous silence of satori (awakening). This silence was not a mere absence of words, but a fullness of presence, a direct communion with the heart of reality. It was the ground from which all authentic expressions of Zen – in art, action, or discourse – emerged.

5. Influence and Legacy

Suzuki’s work had a far-reaching impact on the Western understanding of Zen and Eastern thought more broadly. His books and lectures introduced Zen to a wide audience and sparked a surge of interest in Buddhist practice and philosophy.

In the United States, Suzuki’s ideas influenced a generation of writers, artists, and intellectuals. The Beat poets, in particular, were drawn to Zen’s emphasis on direct experience, spontaneity, and non-conformity. Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Gary Snyder all studied Zen and incorporated its insights into their work.

Suzuki’s writings also had a profound impact on the development of humanistic and transpersonal psychology. His emphasis on the transformative potential of direct experience resonated with thinkers like Abraham Maslow, who saw in Zen a model for the fully actualized human being. The field of mindfulness-based psychotherapy, which has grown exponentially in recent decades, owes much to Suzuki’s pioneering work in bringing Zen practices to the West.

In Japan, Suzuki played a key role in the revival of Zen in the 20th century. His books and lectures helped to rekindle interest in Zen among the Japanese public and to establish it as an important part of the country’s cultural heritage. Suzuki’s work also served to bridge the gap between the Zen monasteries and the wider society, making Zen teachings and practices more accessible to laypeople.

Today, Suzuki’s legacy continues to inspire scholars, practitioners, and seekers around the world. His vision of Zen as a living tradition, intimately connected to the deepest questions of human existence, remains as vital and relevant as ever. As the global dialogue between Eastern and Western spirituality continues to unfold, Suzuki’s work stands as a landmark of cross-cultural understanding and a testament to the transformative power of the Zen experience.

6. Criticism and Controversy

While Suzuki’s contributions to the understanding of Zen in the West are widely recognized, his work has also been the subject of criticism and controversy.

Some scholars have argued that Suzuki’s presentation of Zen was overly romanticized and essentialized, presenting a one-sided view that downplayed the historical and cultural context of the tradition. Critics have pointed out that Suzuki tended to emphasize the transcendent, ahistorical aspects of Zen while glossing over its institutional history and social realities.

Others have accused Suzuki of promoting a kind of Zen nationalism, associating Zen with Japanese cultural superiority and militarism. During the Second World War, Suzuki wrote essays that seemed to justify Japan’s military aggression as an expression of the Zen spirit. While Suzuki later distanced himself from these views, some critics see them as evidence of a problematic strain in his thought.

There have also been questions about Suzuki’s scholarly rigor and accuracy in his translations and interpretations of Zen texts. Some academic Buddhologists have argued that Suzuki took liberties with his source material, reading his own philosophical and spiritual preoccupations into the tradition.

Despite these criticisms, most scholars acknowledge Suzuki’s immense contribution to the field of Zen studies and his role in opening up new avenues of dialogue between East and West. While his work may reflect certain biases and limitations, it remains a starting point for any serious engagement with Zen thought and practice.

7. Personal Life and Practice

Throughout his life, Suzuki remained dedicated to his own Zen practice. He was known for his disciplined daily routine, which included early morning zazen and regular periods of intensive retreat.

Suzuki’s personal demeanor was often described as serene, humble, and deeply present. Students and colleagues noted his ability to give his full attention to each person he encountered, listening deeply and responding with warmth and humor.

At the same time, Suzuki could be fierce and uncompromising in his commitment to the truth of Zen. He had little patience for intellectual speculation or spiritual bypassing, insisting on the necessity of direct practice and realization.

Suzuki was married twice, first to Beatrice Erskine Lane, an American writer and Radcliffe graduate with whom he had a daughter, and later to Mihoko Okamura, a scholar and translator who became his collaborator and companion in his later years.

In his final years, Suzuki continued to write and teach, even as his health declined. He died in Tokyo in 1966 at the age of 95, leaving behind a vast legacy of scholarship and inspiration.

8. Influence and Legacy

D.T. Suzuki’s life and work stand as a testament to the transformative power of Zen and its relevance to the modern world. Through his writings, teachings, and personal example, Suzuki opened up new channels of communication between East and West, challenging prevailing assumptions about the nature of reality and the meaning of spiritual practice.

Suzuki’s vision of Zen as a living tradition, rooted in direct experience and applicable to all aspects of life, continues to inspire practitioners and seekers around the world. His emphasis on the unity of Zen insight and everyday activity, on the interplay of discipline and spontaneity, resonates with the deepest aspirations of the contemporary spiritual search.

At the same time, Suzuki’s legacy invites ongoing critical reflection and dialogue. As Zen takes root in new cultural contexts, it is important to interrogate its historical and ideological baggage, to distinguish the essential from the culturally contingent. Suzuki’s work, for all its brilliance, was not immune to the limitations and biases of its time and place.

The task for contemporary Zen scholars and practitioners is to build on Suzuki’s insights while also subjecting them to rigorous questioning and fresh interpretation. This means engaging with the full complexity of Zen’s history and its intersection with issues of power, identity, and social justice. It means being willing to adapt and evolve the tradition in response to new challenges and contexts.

Ultimately, the enduring value of Suzuki’s work may lie not in any final set of answers, but in the questions it poses and the doors it opens. His life and teachings invite us to plunge into the depths of our own experience, to discover for ourselves the liberating truth of Zen. They challenge us to bring that truth to bear on the pressing issues of our time, to engage wholeheartedly in the work of transformation and awakening.

As we grapple with the great challenges of the 21st century – ecological crisis, social upheaval, existential alienation – the wisdom of Zen, as articulated by Suzuki and others, may prove more relevant than ever. In its insistence on direct encounter with reality, on the unity of contemplation and action, Zen offers a path of radical presence and engagement. It invites us to touch the heart of our lives and to respond with creativity, compassion, and courage.

In this sense, Suzuki’s legacy is not just a matter of historical interest, but an ongoing invitation and provocation. It calls us to awaken to our deepest nature, to take up the great work of our time with a spirit of openness, fearlessness, and joy. As we do so, we join a lineage of seekers and bodhisattvas that stretches back through Suzuki to the Buddha himself, and forward into an uncertain but hopeful future.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

- Suzuki, D.T. (1927). Essays in Zen Buddhism (First Series). London: Luzac.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1933). Essays in Zen Buddhism (Second Series). London: Luzac.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1934). An Introduction to Zen Buddhism. Kyoto: Eastern Buddhist Society.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1938). Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1949). The Zen Doctrine of No-Mind. London: Rider & Company.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1957). Mysticism: Christian and Buddhist. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1960). Manual of Zen Buddhism. New York: Grove Press.

- Abe, Masao. (1986). Zen and Western Thought. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Fields, Rick. (1992). How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. Boston: Shambhala.

- Faure, Bernard. (1993). Chan Insights and Oversights: An Epistemological Critique of the Chan Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995). “The Zen of Japanese Nationalism.” In Curators of the Buddha: The Study of Buddhism Under Colonialism, edited by Donald S. Lopez Jr. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich. (2005). Zen Buddhism: A History (2 vols.). Bloomington: World Wisdom.

- Jung, C.G. (1958). Psychology and Religion: West and East. (Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 11). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kerouac, Jack. (1958). The Dharma Bums. New York: Viking Press.

- Watts, Alan. (1957). The Way of Zen. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Snyder, Gary. (1969). Earth House Hold. New York: New Directions.

- Masunaga, Reiho. (1971). The Soto Approach to Zen. Tokyo: Layman Buddhist Society Press.

- Hisamatsu, Shin’ichi. (1982). Zen and the Fine Arts. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

- Victoria, Brian Daizen. (1997). Zen at War. New York: Weatherhill.

- Sharf, Robert H. (1998). “Experience.” In Critical Terms for Religious Studies, edited by Mark C. Taylor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- McMahan, David L. (2008). The Making of Buddhist Modernism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tweed, Thomas A. (2005). “American Occultism and Japanese Buddhism: Albert J. Edmunds, D. T. Suzuki, and Translocative History.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32(2): 249-281.

- Borup, Jørn. (2004). “Zen and the Art of Inverting Orientalism: Religious Studies and Genealogical Networks.” In New Approaches to the Study of Religion: Regional, Critical, and Historical Approaches, edited by Peter Antes, Armin W. Geertz, and Randi R. Warne. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Snodgrass, Judith. (2003). Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbian Exposition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Jaffe, Richard M. (2019). Seeking Sakyamuni: South Asia in the Formation of Modern Japanese Buddhism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

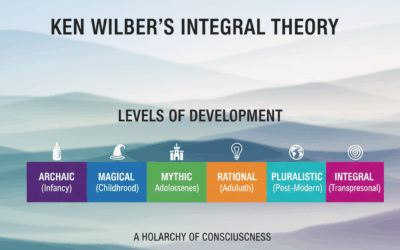

Jungian Innovators

0 Comments