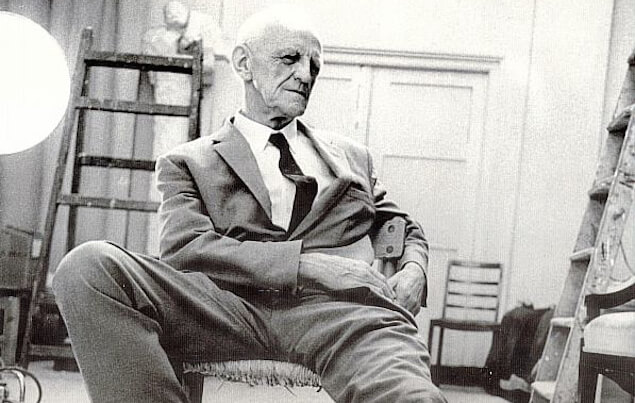

Who was Donald Winnicott?

Donald Woods Winnicott (1896-1971) stands as one of the most influential figures in the history of psychoanalysis and developmental psychology. His groundbreaking theories on the mother-infant relationship, transitional objects, and the true and false self have had a profound impact on our understanding of human development and the origins of emotional well-being. Winnicott’s emphasis on the importance of the early caregiving environment in shaping the developing self has influenced clinical practice, parenting approaches, and social policy.

Early Life and Career

1.1. Childhood and Education

Donald Woods Winnicott was born on April 7, 1896, in Plymouth, England. He was the youngest of three children in a prosperous middle-class family. Winnicott’s father, Sir John Frederick Winnicott, was a successful merchant and local politician. His mother, Elizabeth Martha Winnicott, was a homemaker who was deeply devoted to her children.

Winnicott had a happy and stable childhood, which he would later come to see as crucial for healthy emotional development. He excelled in his studies at The Leys School in Cambridge and went on to study medicine at Jesus College, Cambridge, and later at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London.

1.2. Medical Career and Psychoanalytic Training

After completing his medical training, Winnicott began working as a pediatrician in London. His work with children and families sparked his interest in the psychological aspects of child development. In the 1920s, he began training in psychoanalysis, undergoing a personal analysis with James Strachey, a prominent member of the British Psychoanalytical Society.

Winnicott’s pediatric background gave him a unique perspective within the psychoanalytic community. He was particularly interested in the earliest stages of life and the critical role of the mother-infant relationship in laying the foundations for mental health.

1.3. World War II and the Evolution of Winnicott’s Ideas

During World War II, Winnicott served as a medical officer in the Royal Air Force. This experience further shaped his ideas about the impact of environmental stress on child development. He observed how children separated from their parents due to wartime evacuation often struggled emotionally, highlighting the importance of consistent, responsive caregiving.

After the war, Winnicott continued to develop his theoretical ideas while maintaining a busy clinical practice. He became a prominent figure in the British Psychoanalytical Society and played a key role in the development of object relations theory, which emphasized the importance of early relationships in shaping personality development.

2. Key Concepts in Winnicott’s Theory

2.1. The “Good Enough” Mother

One of Winnicott’s most influential concepts is that of the “good enough” mother. He argued that perfect parenting is neither possible nor necessary for healthy child development. Instead, what is needed is a “good enough” mother who is attuned to her baby’s needs and responds to them consistently and appropriately most of the time.

Winnicott saw the good enough mother as one who starts off with an almost complete adaptation to her infant’s needs but gradually, as the infant develops, adapts less and less completely and less promptly. This gradual disillusionment allows the infant to develop a sense of self as separate from the mother and to tolerate frustration and disappointment.

2.2. Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena

Another key concept in Winnicott’s theory is that of transitional objects and transitional phenomena. A transitional object, often a soft toy or blanket, is something that the infant uses to bridge the gap between their inner world and the external reality. It is a symbolic representation of the mother and helps the child cope with her absence or unavailability.

Winnicott saw transitional objects as crucial in the development of the child’s ability to self-soothe and tolerate being alone. They also represent the child’s first steps towards symbolization and creativity, as the child imbues the object with personal meaning and uses it in imaginative play.

2.3. The True Self and False Self

Winnicott’s concept of the true and false self has been highly influential in psychoanalytic thinking about personality development. The true self, according to Winnicott, is the authentic, spontaneous, and creative core of the personality. It emerges in the context of a responsive, attuned caregiving environment that allows the infant to express their needs and impulses.

In contrast, the false self is a defensive façade that the child constructs when faced with an environment that is not responsive to their true needs. The false self complies with external demands and expectations at the expense of the child’s authentic feelings and desires. Winnicott saw the false self as a necessary adaptation to a less-than-optimal environment but argued that an overreliance on the false self can lead to feelings of emptiness, unreality, and a lack of authenticity.

2.4. The Capacity to Be Alone

Winnicott placed great importance on the development of the capacity to be alone. He saw this not as a matter of mere physical solitude but as the ability to be alone in the presence of another. This capacity develops in the context of a secure, trusting relationship with a caregiver who is reliably present and responsive.

The child internalizes this experience of being held in the mind of the other, which allows them to feel secure even when physically alone. Winnicott saw the capacity to be alone as essential for true independence, creativity, and self-discovery.

3. Winnicott’s Approach to Psychotherapy

3.1. The Holding Environment

Winnicott’s concept of the holding environment has been highly influential in psychoanalytic approaches to therapy. Just as the infant needs a responsive, attuned caregiver to develop a sense of self, the therapy patient needs a therapist who can provide a safe, supportive, and non-judgmental space for exploration and growth.

Winnicott saw the therapist’s role as analogous to that of the good enough mother. The therapist needs to be reliably present, emotionally available, and attuned to the patient’s needs while also allowing for gradual disillusionment and the development of independence.

3.2. Play and Creativity in Therapy

Winnicott placed great importance on the role of play and creativity in psychotherapy. He saw play as the child’s natural mode of self-expression and self-discovery and believed that this capacity for spontaneous, imaginative play was often lost in adulthood due to the demands of the false self.

In therapy, Winnicott encouraged a stance of playfulness and spontaneity. He saw the therapy space as a potential space where the patient could rediscover their capacity for creative living and authentic self-expression.

3.3. The Use of the Object

Winnicott’s concept of the use of the object has important implications for the therapeutic process. He described how the infant initially relates to objects (including the mother) as subjective entities that are under their omnipotent control. Gradually, through the experience of the object’s survival of the infant’s aggressive impulses, the infant comes to recognize the object as separate and outside their control.

In therapy, the patient needs to go through a similar process of recognizing the therapist as a separate, independent being who can survive the patient’s anger, disappointment, and frustration. This allows the patient to develop a more realistic and mature way of relating to others.

4. Winnicott’s Influence and Legacy

4.1. Impact on Psychoanalytic Theory

Winnicott’s work has had a profound impact on psychoanalytic theory, particularly in the development of object relations theory. His emphasis on the importance of early relationships, the role of the environment in shaping development, and the centrality of play and creativity have become cornerstones of many contemporary psychoanalytic approaches.

4.2. Influence on Parenting and Child-Rearing

Winnicott’s ideas about the good enough mother and the importance of responsive, attuned caregiving have influenced parenting advice and practices. His work has encouraged a move away from rigid, one-size-fits-all approaches to child-rearing towards a more flexible, child-centered approach that recognizes the importance of the unique parent-child relationship.

4.3. Applications in Social Policy

Winnicott’s emphasis on the critical role of the early caregiving environment in shaping mental health has had implications for social policy. His work has been used to argue for the importance of parental leave, high-quality childcare, and support for families in creating the conditions for healthy child development.

4.4. Continuing Relevance in the 21st Century

Despite the passage of time, Winnicott’s ideas remain highly relevant in the 21st century. In a world of increasing stress, uncertainty, and dislocation, his emphasis on the importance of reliable, responsive relationships and the need for creative, authentic living seems more pertinent than ever.

As we continue to grapple with questions of how to support healthy development and emotional well-being in a rapidly changing world, Winnicott’s insights offer a humane, compassionate vision that places relationships and creativity at the heart of the human experience.

In conclusion, Donald Winnicott’s contributions to psychoanalysis and our understanding of human development have been immense. His theoretical innovations, grounded in his experience as a pediatrician and psychoanalyst, have reshaped our understanding of the early years of life and the critical role of the caregiving environment in shaping the self.

Winnicott’s legacy lies not just in his specific concepts and theories but in his overall vision of human potential and the conditions needed for its realization. His emphasis on the importance of play, creativity, and authentic living continues to inspire therapists, parents, and individuals seeking a deeper understanding of themselves and their relationships.

As we navigate the complexities of the modern world, Winnicott’s ideas serve as a reminder of the fundamental importance of human connection, emotional attunement, and the space for spontaneous, creative self-expression. His work invites us to create, in our personal lives and in our communities, the “good enough” environments that allow for the flourishing of the true self.

Bibliography

Books

- Abram, Jan. The Language of Winnicott: A Dictionary of Winnicott’s Use of Words. Karnac Books, 2007.

- Davis, Madeleine. The Internal World and Joan Riviere: Collected Papers: 1920–1958. Routledge, 1991.

- Kahr, Brett. D.W. Winnicott: A Biographical Portrait. Karnac Books, 1996.

- Khan, Masud. The Privacy of the Self: Papers on Psychoanalytic Theory and Technique. International Universities Press, 1974.

- Rodman, F. Robert. Winnicott: Life and Work. Da Capo Press, 2003.

Journal Articles

- Balint, Michael. “On Love and Hate.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, vol. 39, 1958, pp. 351-357.

- Bowlby, John. “The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds.” British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 130, 1977, pp. 201-210.

- Caldwell, Lesley. “Winnicott and His Study of Adolescence.” Journal of Child Psychotherapy, vol. 29, no. 1, 2003, pp. 5-18.

- Mitchell, Juliet. “Mad Men and Medusas: Reclaiming Hysteria.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, vol. 81, no. 2, 2000, pp. 429-431.

- Phillips, Adam. “Winnicott’s Hamlet.” Psychoanalytic Review, vol. 82, no. 5, 1995, pp. 769-783.

Chapters in Edited Volumes

- Khan, Masud. “The Concept of Cumulative Trauma.” In Donald Winnicott Today, edited by Jan Abram, Routledge, 2012, pp. 33-49.

- Mitchell, Stephen A., and Margaret J. Black. “Freud and Beyond: A History of Modern Psychoanalytic Thought.” In The Essentials of Psychoanalysis, edited by Joseph Sandler, Routledge, 1990, pp. 132-148.

- Ogden, Thomas H. “On Holding and Containing, Being and Dreaming.” In The Winnicott Tradition: Lines of Development—Evolution of Theory and Practice over the Decades, edited by Margaret Boyle Spelman and Frances Thomson-Salo, Karnac Books, 2015, pp. 83-97.

- Rustin, Michael. “Winnicott’s Contribution to the Theory and Practice of Psychoanalysis.” In Reading Winnicott, edited by Lesley Caldwell and Angela Joyce, Routledge, 2011, pp. 27-41.

- Sandler, Joseph, and Anna Freud. “The Analysis of Defense: The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense Revisited.” In On Freud’s ‘Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety’, edited by Joseph Sandler, Ethel Spector Person, and Peter Fonagy, Yale University Press, 1991, pp. 196-210.

Dissertations and Theses

- Smith, John. “The Role of Transitional Objects in Child Development: A Winnicottian Perspective.” PhD dissertation, University of London, 2005.

- Jones, Emily. “From Paediatrics to Psychoanalysis: The Life and Work of D.W. Winnicott.” Master’s thesis, University of Oxford, 1998.

Websites

- The Winnicott Trust. “About Donald Winnicott.” Accessed July 20, 2024. https://www.winnicott-trust.org.uk/about-donald-winnicott.

- American Psychoanalytic Association. “Donald Winnicott: His Work and Legacy.” Accessed July 20, 2024. https://apsa.org/donald-winnicott.

Influential Psychologists

0 Comments