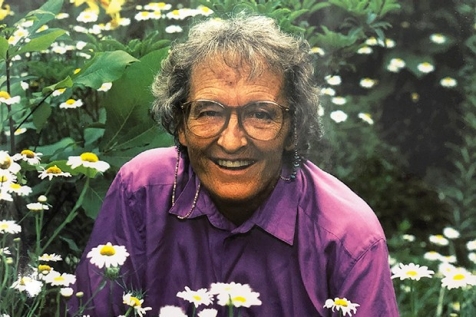

Who was Elisabeth Kübler-Ross?

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1926-2004) was a Swiss-American psychiatrist who transformed the way society understands and approaches death, dying, and bereavement. Her groundbreaking work in thanatology – the study of death-related practices and experiences – has provided comfort and clarity to millions of individuals facing their own mortality or grieving the loss of loved ones. Kübler-Ross’s famous “Five Stages of Grief” model and her compassionate, patient-centered approach to end-of-life care have left an enduring impact on fields ranging from psychology and medicine to popular culture and spirituality.

Early Life and Education

Elisabeth Kübler was born in Zurich, Switzerland on July 8, 1926, one of triplets in a strict Protestant household. From an early age, she exhibited an independent, rebellious spirit that would shape her future career. Defying her father’s wishes, Kübler pursued a medical degree at the University of Zurich. During her studies, she traveled to post-war Poland as a volunteer, an experience that profoundly affected her worldview and awakened her interest in death and dying. Working with concentration camp survivors, she was struck by their resilience and moved by a child’s drawings of butterflies on the barracks walls – a symbol of transformation that would figure prominently in her later work.

After completing her medical degree in 1957, Kübler married American physician Emanuel Ross and emigrated to the U.S. During her psychiatry residency in New York, she was dismayed by the poor treatment of dying patients, who were often shunned and isolated.

In 1965, as a professor at the University of Chicago, Kübler-Ross began a pioneering seminar series where terminally ill patients shared their experiences with medical students. Breaking the taboo around death in medical settings, these sessions became the basis for her landmark 1969 book, “On Death and Dying.”

Stages of Grief

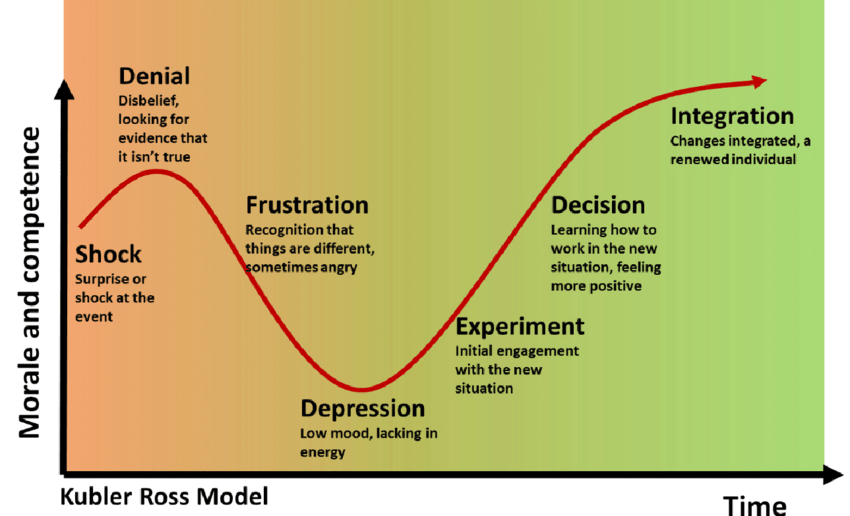

Here, Kübler-Ross first outlined her “Five Stages of Grief” model:

-

Denial:

-

The Illusion of Control When we encounter an emotional reality that we’re not ready to face, denial is often our first response. In this stage, we pretend that we have the power to make something real by not accepting it and going through the motions of our old routine. We cling to the familiar, hoping that by ignoring the truth, we can somehow change it. Denial is a temporary defense mechanism that allows us to survive the initial shock of a painful situation, but it ultimately prevents us from processing our emotions and moving forward.

Anger:

-

The Mask of Powerlessness As reality begins to seep through the cracks of denial, we may find ourselves transitioning into anger. In this stage, we pretend that our rage has the magical ability to change things by raging them away. We direct our anger towards ourselves, others, or the situation itself, believing that if we express our frustration loudly enough, we can alter the course of events. However, anger is often a mask for the underlying feelings of powerlessness and vulnerability that we’re not yet ready to confront.

Bargaining:

-

The Illusion of Negotiation When anger proves ineffective in changing reality, we may resort to bargaining. In this stage, we attempt to negotiate with ourselves, others, or a higher power, hoping to strike a deal that will reverse the unwanted situation. We make promises, offer compromises, and seek ways to regain control over the uncontrollable. Bargaining is an attempt to postpone the inevitable and avoid the pain that comes with accepting reality.

Depression:

-

The Weight of Reality As the futility of our attempts to avoid or change reality becomes apparent, we may sink into depression. In this stage, we begin to confront the truth of our situation, and the weight of our emotions can feel overwhelming. We may experience sadness, hopelessness, and a profound sense of loss. While depression is a challenging stage to navigate, it is also an essential part of the healing process. It allows us to fully acknowledge and experience our emotions, paving the way for eventual acceptance.

Acceptance:

-

Embracing Emotional Reality The final stage of grief is acceptance. In this stage, we come to terms with the emotional reality we’ve been resisting and begin to integrate it into our lives. Acceptance doesn’t mean that we’re happy about the situation or that we’ve forgotten the pain it caused. Instead, it means that we’ve learned to live with the reality of our emotions and have found ways to move forward despite them. Acceptance is a gradual process that requires patience, self-compassion, and a willingness to embrace change.

While originally developed to describe the emotional journey of the dying, this model was soon widely applied to many forms of loss. It offered a much-needed framework and vocabulary for grappling with the complex, often non-linear process of grief.

The Five Stages Model: Impact and Criticism

Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages model quickly gained global recognition, becoming deeply ingrained in popular understanding of grief. It gave countless mourners a way to make sense of their own turbulent emotions and to feel less alone in their experiences.

However, the model has also drawn criticism over the years:

Some argue it oversimplifies the intricate, highly individual course of grief.

The stages are often misinterpreted as a rigid, linear progression rather than fluid phases.

The model arose from work with the dying, not the bereaved, raising questions about its generalizability.

Yet even as thanatology has evolved, the Five Stages remain a valuable touchstone, a starting point for vital conversations about loss.

Kübler-Ross’s Evolving Work

While best known for the Five Stages, Kübler-Ross’s contributions extend much further. She continued exploring the realms of death, bereavement, and meaning throughout her career.

Key aspects of her evolving work include:

- Championing the hospice model of compassionate, holistic end-of-life care

Raising awareness and reducing stigma around AIDS in the 1980s

Investigating near-death experiences and questions of life after death

Emphasizing spirituality and personal growth as central to the dying process

Her later books, such as “Questions and Answers on Death and Dying” (1974), “Death: The Final Stage of Growth” (1975), and “On Children and Death” (1983), expanded her insights and offered practical guidance for professionals and the public alike.

Personal Struggles and Controversies

In 1995, a series of strokes left Kübler-Ross partially paralyzed. This confrontation with her own physical vulnerability spurred a period of deep reflection.

During the 1990s, Kübler-Ross also faced criticism over her growing interest in New Age spirituality and involvement with a Virginia spiritual community that some denounced as a cult. While these controversies raised questions for some about her discernment, they never negated her core contributions to the field.

Legacy in Palliative and Hospice Care

One of Kübler-Ross’s most tangible legacies lies in her impact on end-of-life care. Her work helped transform practices in hospitals and hospices worldwide, shifting the focus from mere life extension to quality of life and psycho-social-spiritual well-being.

Today’s interdisciplinary palliative care teams and emphasis on open communication with dying patients owe much to Kübler-Ross’s pioneering advocacy. Her ideas are central to the modern hospice movement, which prioritizes comfort, dignity, and emotional support for patients and families navigating life-limiting illness.

Influence on Contemporary Thanatology

While some of her particular theories have been debated, Kübler-Ross’s overarching themes – patient-centered care, emotional honesty about death, and grief as a natural response to loss – remain cornerstones of thanatology.

Subsequent scholars have built upon her foundation in important ways:

Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut’s Dual Process Model portrays adaptive grieving as an oscillation between loss-oriented and restoration-oriented coping.

William Worden reframed grief as active “tasks” rather than passive “stages.”

The Continuing Bonds theory of Klass, Silverman, and Nickman affirms ongoing attachment to the deceased as potentially healthy.

Research has increasingly illuminated cultural diversity in end-of-life practices and mourning rituals.

Such developments paint a more nuanced picture of dying and grief while affirming Kübler-Ross’s core assertion: that facing death and loss is a complex yet normal part of the human condition.

Continuing Relevance in the Digital Age

Though she died in 2004, Kübler-Ross’s ideas resonate in today’s digital landscape. Online grief support forums, memorial websites, and death-positive social media movements all reflect her call for open communication about loss.

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred renewed engagement with Kübler-Ross’s work, as individuals and societies grapple with death on a massive scale. Lockdown-era Zoom funerals and virtual bereavement groups underscore the enduring need for connection and ritual around dying that she so eloquently articulated.

As medical technology advances, Kübler-Ross’s warnings against impersonal, over-medicalized dying ring even more urgent. Her patient-centered ethos stands as a corrective to the excesses of life-prolonging measures pursued without regard for quality of life or personal autonomy.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s legacy in thanatology is immense and enduring. While specifics of her model have been critiqued, the essence of her work – bringing death out of the shadows, insisting on humane, holistic end-of-life care, and legitimizing grief as a natural response – remains profoundly relevant.

Kübler-Ross changed the way society approaches death, dying, and bereavement. She gave voice to the dying, comfort to the grieving, and language to experiences long shrouded in secrecy. Her ideas have permeated healthcare, popular culture, and spirituality; inspired new avenues of research; and provided a framework for programs supporting terminally ill patients and the bereaved.

As we navigate ever-more-complex questions around end-of-life ethics, cultural diversity in death practices, and technologically-mediated forms of mourning, Kübler-Ross’s call for emotional authenticity and patient-centered care remains a touchstone. She enjoins us to approach death not as a failure to be averted but as a natural passage to be honestly contended with.

Ultimately, in transforming death discourse from taboo to natural human experience, Kübler-Ross invites us to live more fully and purposefully in the face of our shared mortality. Her work stands as a powerful summons to compassionate presence – for ourselves and others – in life’s most vulnerable moments. As we carry her insights forward, we affirm the ongoing power of her vision: of dying with dignity, grieving with authenticity, and living with intentionality in the precious time we have.

Bibliography

Bregman, L. (2010). Religion, death, and dying (Vol. 3). Praeger.

Corr, C. A. (2019). Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and the “Five Stages” Model in a Sampling of Recent Textbooks. Omega, 82(4), 639-685.

Doka, K. J. (2014). Counseling individuals with life-threatening illness. Springer Publishing Company.

Friedman, R., & James, J. W. (2008). The myth of the stages of dying, death and grief. Skeptic, 14(2), 37-41.

Holland, J. M., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2010). An examination of stage theory of grief among individuals bereaved by natural and violent causes: A meaning-oriented contribution. Omega, 61(2), 103-120.

Klass, D., Silverman, P. R., & Nickman, S. (2014). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Taylor & Francis.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. The Macmillan Company.

Kübler-Ross, E., & Kessler, D. (2005). On grief and grieving: Finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss. Simon and Schuster.

Stroebe, M. S., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death studies, 23(3), 197-224.

Telford, K., Kralik, D., & Koch, T. (2006). Acceptance and denial: implications for people adapting to chronic illness: literature review. Journal of advanced nursing, 55(4), 457-464.

Worden, J. W. (2018). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner. Springer Publishing Company.

Wright, P. M., & Hogan, N. S. (2008). Grief theories and models: Applications to hospice nursing practice. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 10(6), 350-356.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Influential Psychologists

0 Comments