Who was Søren Kierkegaard?

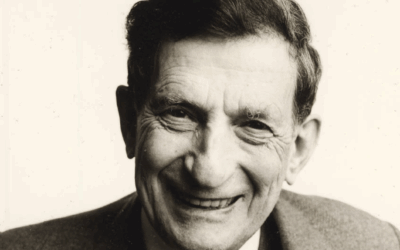

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) was a Danish philosopher, theologian, and author widely regarded as the first existentialist philosopher. His work explored the nature of human existence, emphasizing individuality, personal choice and commitment, and the struggle with anxiety and despair in the face of life’s uncertainties. Kierkegaard’s ideas profoundly influenced later existentialist thinkers as well as psychologists and psychotherapists grappling with the complexities of the human psyche.

Life and Career

Kierkegaard was born in Copenhagen in 1813 to a wealthy and devout Lutheran family. He studied theology and philosophy at the University of Copenhagen but was more drawn to literature and philosophy than to a career in the church. A pivotal event in his life was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen in 1841, an experience that shaped his reflections on love, commitment, and the self.

Throughout the 1840s, Kierkegaard wrote prolifically, publishing major works such as Either/Or (1843), Fear and Trembling (1843), The Concept of Anxiety (1844), and The Sickness Unto Death (1849). He used various pseudonyms to explore different perspectives and to communicate indirectly with readers, challenging them to confront their own existential choices.

In his final years, Kierkegaard became increasingly critical of the Danish Lutheran Church, seeing it as a complacent and inauthentic institution. He died in 1855 at the age of 42, leaving behind a rich and complex philosophical legacy.

Timeline of Kierkegaard’s Life

1813: Born in Copenhagen, Denmark 1830: Enters the University of Copenhagen to study theology and philosophy 1841: Becomes engaged to Regine Olsen but breaks off the engagement shortly after 1843: Publishes Either/Or and Fear and Trembling 1844: Publishes The Concept of Anxiety

1845: Publishes Stages on Life’s Way 1846: Publishes Concluding Unscientific Postscript 1847: Publishes Works of Love 1849: Publishes The Sickness Unto Death and Two Minor Ethical-Religious Essays 1850: Publishes Training in Christianity 1855: Publishes his final work, The Moment, and dies in Copenhagen

Key Ideas

Existence and the Single Individual: Kierkegaard emphasized the primacy of individual existence over abstract thinking and speculative philosophy. For him, the task of philosophy was not to construct grand systems but to elucidate the concrete situation of the existing individual. He critiqued the Hegelian notion of the universal, arguing that it failed to capture the unique, subjective experience of the single individual.

The Stages of Existence: In works such as Either/Or, Kierkegaard outlined three primary stages or spheres of existence: the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious. The aesthetic stage is characterized by the pursuit of pleasure, novelty, and avoidance of commitment. The ethical stage involves taking responsibility and making choices based on moral duty. The religious stage entails a leap of faith and a passionate, subjective relationship to God. For Kierkegaard, the goal was to move from the aesthetical, through the ethical, to the religious.

Anxiety and Despair: Kierkegaard explored the psychological states of anxiety and despair as fundamental to the human condition. In The Concept of Anxiety, he described anxiety as the dizzying freedom of possibility that confronts the individual. Despair, as elaborated in The Sickness Unto Death, is the misrelation of the self to itself, the failure to synthesize the finite and infinite aspects of the self. For Kierkegaard, grappling with anxiety and despair was essential to authentic existence.

Faith and the Absurd: In works such as Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard reflected on the nature of religious faith, using the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac to illustrate the “teleological suspension of the ethical.” True faith, for Kierkegaard, involves a passionate commitment to God that transcends rational understanding and ethical norms. The knight of faith embraces the absurd and makes the leap into the unknown.

Indirect Communication: Kierkegaard employed an innovative literary style characterized by pseudonyms, irony, and indirect communication. Rather than conveying his ideas directly, he sought to stimulate readers’ self-reflection and to provoke them into confronting their own existential choices. His aim was not to provide ready-made answers but to serve as a “midwife” for the truth that each individual must discover within themselves.

Kierkegaard’s Conceptualization of Trauma

While Kierkegaard did not use the modern language of trauma, his existential philosophy grappled with the profound challenges and crises of human existence that can be understood as traumatic. For Kierkegaard, the human condition is inherently anxious, as we are confronted with the dizzying freedom and responsibility of shaping our own lives. This existential anxiety can be overwhelming, leading to despair, which Kierkegaard saw as a sickness of the self.

In works such as The Concept of Anxiety and The Sickness Unto Death, Kierkegaard explored the psychological impact of facing the uncertainties and absurdities of life. He described the experience of dread or angst as a fundamental human state that arises from our awareness of our own freedom and the impossibility of finding absolute certainty or security in the world. This state can be deeply unsettling, shattering our illusions of control and forcing us to confront the existential void.

Kierkegaard also recognized the traumatic impact of certain life events and transitions. His own experience of breaking off his engagement to Regine Olsen left him wrestling with guilt, regret, and self-recrimination. He saw such personal crises as opportunities for growth and self-transformation, but also acknowledged the pain and suffering they entail.

For Kierkegaard, the ultimate response to the traumas of existence was not to seek escape or distraction, but to embrace them as part of the human condition. By facing our anxiety and despair head-on, and by making the leap of faith into the unknown, we can transcend our limitations and find meaning and authenticity in life. This involves a willingness to confront the absurdities and paradoxes of existence, to take responsibility for our choices, and to commit ourselves passionately to our beliefs and values.

Kierkegaard’s vision of the self as a synthesis of the finite and the infinite, the temporal and the eternal, also has implications for understanding trauma. Traumatic experiences can disrupt our sense of self and shatter our assumptions about the world. Recovering from trauma involves a process of reconstructing the self, of finding new ways to integrate the painful experiences into a coherent narrative. Kierkegaard’s emphasis on the ongoing task of becoming a self, of continually striving to reconcile the opposing elements of our nature, can offer a framework for this process of post-traumatic growth.

Insights from Psychology and Anthropology

Kierkegaard’s existential philosophy anticipated many of the insights of 20th-century psychology and anthropology. His emphasis on the individual’s subjective experience and on the challenges of self-becoming resonates with the humanistic and existential traditions in psychology. Psychologists such as Rollo May, Irvin Yalom, and Emmy van Deurzen have drawn on Kierkegaard’s ideas to explore the existential dimensions of psychotherapy and to develop approaches that emphasize meaning, authenticity, and personal responsibility.

Kierkegaard’s understanding of anxiety as a fundamental human condition has been supported by research in psychology and neuroscience. Studies have shown that anxiety is a natural response to uncertainty and existential threats, and that it can serve both adaptive and maladaptive functions. Kierkegaard’s distinction between normal and neurotic anxiety has informed psychological theories of anxiety disorders and their treatment.

Anthropologists have also found resonance with Kierkegaard’s ideas, particularly his emphasis on the cultural and historical situatedness of human existence. Kierkegaard recognized that individuals are shaped by their social and cultural contexts, even as they struggle to assert their individuality and autonomy. His analysis of the “present age” as a time of leveling and conformity anticipates anthropological critiques of mass society and the pressures of globalization.

At the same time, Kierkegaard’s focus on the individual’s subjective experience and personal responsibility challenges anthropological tendencies to reduce human behavior to social and cultural determinants. His insistence on the irreducibility of the single individual serves as a reminder of the limits of generalizations and the importance of attending to the particular and the unique.

Kierkegaard’s reflections on religious faith and the absurd also have anthropological implications. His understanding of faith as a passionate commitment that transcends rational understanding resonates with anthropological studies of religious experience and ritual. His notion of the “knight of faith” who embraces the paradoxes and uncertainties of existence can be seen as a model of religious subjectivity that challenges conventional notions of belief and practice.

Relevance to Psychotherapy

The Importance of Subjectivity: Kierkegaard’s emphasis on individual subjectivity resonates with the humanistic and existential approaches to psychotherapy that emerged in the 20th century. His focus on the unique, lived experience of the individual aligns with therapeutic approaches that prioritize the client’s perspective and meaning-making processes. Therapists influenced by Kierkegaard seek to understand and validate the client’s subjective reality.

Anxiety and Self-Awareness: Kierkegaard’s conceptualization of anxiety as the confrontation with freedom and possibility has informed existential therapies’ understanding of the role of anxiety in human existence. Therapists may work with clients to explore their anxiety not merely as a pathological symptom but as an opportunity for increased self-awareness and authentic living. By confronting anxiety, clients can gain insight into their choices and values.

Authenticity and Responsibility: Kierkegaard’s notion of the stages of existence and the movement towards greater authenticity can provide a framework for therapeutic growth. Therapists may help clients examine the aesthetic, ethical, and religious/existential dimensions of their lives and to take responsibility for their choices. The goal is not necessarily to prescribe a particular way of living but to facilitate the client’s own discovery of an authentic path.

Despair and Self-Integration: Kierkegaard’s analysis of despair as a misrelation of the self to itself can inform therapeutic understanding of psychological distress. Therapists may work with clients to identify and address the ways in which they are not integrating aspects of their selves or living in alignment with their deepest values. The therapeutic process can be seen as a journey towards greater self-acceptance and wholeness.

Indirect Communication and the Therapeutic Relationship: Kierkegaard’s use of indirect communication and his resistance to providing straightforward answers can serve as a model for the therapeutic relationship. Rather than offering direct advice or solutions, therapists influenced by Kierkegaard may use questioning, paradox, and other indirect means to stimulate clients’ self-reflection and personal insight. The therapist serves as a facilitator of the client’s own process of discovery.

Conclusion

Søren Kierkegaard’s philosophical explorations of existence, anxiety, despair, faith, and the self continue to resonate with contemporary concerns and to inspire new approaches to psychotherapy. While he wrote in a different historical and cultural context, his insights into the human condition remain relevant for therapists seeking to understand and alleviate psychological suffering. By engaging with Kierkegaard’s ideas, therapists can deepen their appreciation for the complexities of human subjectivity and the challenges of living an authentic, meaningful life in the face of existential uncertainties.

Key Takeaways

- Søren Kierkegaard was a Danish philosopher who is widely regarded as the first existentialist thinker.

- His work emphasized individual subjectivity, personal choice and commitment, and the confrontation with anxiety and despair.

- Kierkegaard outlined three stages of existence – the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious – and explored the psychological states of anxiety and despair as fundamental to the human condition.

- Kierkegaard’s ideas have influenced humanistic and existential approaches to psychotherapy, informing understandings of anxiety, authenticity, despair, and the therapeutic relationship.

- Engaging with Kierkegaard’s thought can deepen therapists’ appreciation for the complexities of human existence and inspire new approaches to facilitating clients’ growth and self-understanding.

Bibliography

- The Concept of Anxiety by Søren Kierkegaard

- The Sickness Unto Death by Søren Kierkegaard

- Either/Or by Søren Kierkegaard

- Fear and Trembling by Søren Kierkegaard

- The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich

- Existential Psychotherapy by Irvin D. Yalom

- The Discovery of Being by Rollo May

- Kierkegaard: A Biography by Alastair Hannay

- Kierkegaard’s Concept of Existence by Gregor Malantschuk

- Kierkegaard’s Psychology by Gregor Malantschuk

- Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic by Theodor W. Adorno

- Kierkegaard: An Introduction by C. Stephen Evans

- Kierkegaard and Existentialism edited by Jon Stewart

Digital, Media, and Cultural Theorists and Philosophers

Bernays and The Psychology of Advertising

Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver

0 Comments